Where, Where To, and When in the Occupied Territories: an Introduction to Geography of Disaster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arrested Development: the Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank

B’TSELEM - The Israeli Information Center for ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT Human Rights in the Occupied Territories 8 Hata’asiya St., Talpiot P.O. Box 53132 Jerusalem 91531 The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Tel. (972) 2-6735599 | Fax (972) 2-6749111 Barrier in the West Bank www.btselem.org | [email protected] October 2012 Arrested Development: The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank October 2012 Research and writing Eyal Hareuveni Editing Yael Stein Data coordination 'Abd al-Karim Sa'adi, Iyad Hadad, Atef Abu a-Rub, Salma a-Deb’i, ‘Amer ‘Aruri & Kareem Jubran Translation Deb Reich Processing geographical data Shai Efrati Cover Abandoned buildings near the barrier in the town of Bir Nabala, 24 September 2012. Photo Anne Paq, activestills.org B’Tselem would like to thank Jann Böddeling for his help in gathering material and analyzing the economic impact of the Separation Barrier; Nir Shalev and Alon Cohen- Lifshitz from Bimkom; Stefan Ziegler and Nicole Harari from UNRWA; and B’Tselem Reports Committee member Prof. Oren Yiftachel. ISBN 978-965-7613-00-9 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................ 5 Part I The Barrier – A Temporary Security Measure? ................. 7 Part II Data ....................................................................... 13 Maps and Photographs ............................................................... 17 Part III The “Seam Zone” and the Permit Regime ..................... 25 Part IV Case Studies ............................................................ 43 Part V Violations of Palestinians’ Human Rights due to the Separation Barrier ..................................................... 63 Conclusions................................................................................ 69 Appendix A List of settlements, unauthorized outposts and industrial parks on the “Israeli” side of the Separation Barrier .................. 71 Appendix B Response from Israel's Ministry of Justice ....................... -

West Bank Barrier Route Projections July 2009

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs LEBANON SYRIA West Bank Barrier Route Projections July 2009 West Bank Gaza Strip JORDAN Barta'a ISRAEL ¥ EGYPT Area Affected r The Barrier’s total length is 709 km, more than e v i twice the length of the 1949 Armistice Line R n (Green Line) between the West Bank and Israel. W e s t B a n k a d r o The total area located between the Barrier J and the Green Line is 9.5 % of the West Bank, Qalqilya including East Jerusalem and No Man's Land. Qedumim Finger When completed, approximately 15% of the Barrier will be constructed on the Green Line or in Israel with 85 % inside the West Bank. Biddya Area Populations Affected Ari’el Finger If the Barrier is completed based on the current route: Az Zawiya Approximately 35,000 Palestinians holding Enclave West Bank ID cards in 34 communities will be located between the Barrier and the Green Line. The majority of Palestinians with East Kafr Aqab Jerusalem ID cards will reside between the Barrier and the Green Line. However, Bir Nabala Enclave Biddu Palestinian communities inside the current Area Shu'fat Camp municipal boundary, Kafr Aqab and Shu'fat No Man's Land Camp, are separated from East Jerusalem by the Barrier. Ma’ale Green Line Adumim Settlement Jerusalem Bloc Approximately 125,000 Palestinians will be surrounded by the Barrier on three sides. These comprise 28 communities; the Biddya and Biddu areas, and the city of Qalqilya. ISRAEL Approximately 26,000 Palestinians in 8 Gush a communities in the Az Zawiya and Bir Nabala Etzion e Enclaves will be surrounded on four sides Settlement S Bloc by the Barrier, with a tunnel or road d connection to the rest of the West Bank. -

Internal and External Security Dynamics of Qatari Policy Toward the Syria Uprising

Comillas Journal of International Relations | nº 05 | 065-077 [2016] [ISSN 2386-5776] 65 DOI: cir.i05.y2016.005 INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL SECURITY DYNAMICS OF QATARI POLICY TOWARD THE SYRIA UPRISING Las dinámicas de seguridad internas y externas de la política de Catar frente al levantamiento sirio Kristian Coates Ulrichsen Fellow for the Middle East, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy Autor Affiliate Professor, Henry M Jackson School of International Studies, University of Washington-Seattle E-mail: [email protected] Qatar played a leading role in supporting the opposition to Bashar al-Assad since the beginning of the Syrian uprising in 2011. While Kuwait emerged as a key (unofficial) conduit for financial Abstract transfers from the Gulf States to Syria and backing from Saudi Arabia initially took the form of illicit flows of militants and weapons to groups of opposition fighters, Qatar from the start adopted a political approach to organizing the Syrian opposition, in addition to providing tens of millions of dollars to rebel groups. Qatari support increasingly controversial as it was perceived to be tied to groups linked to the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood. During 2012, Qatar and Saudi Arabia backed competing groups, contributing to the fragmentation of the opposition, before responsibility for the “Syria file” passed decisively from Doha to Riyadh in spring 2013. This signified a major setback to Qatar’s ambition to become a regional power and highlighted how Qatar’s Syria policy was undermined by the lack of institutional capacity to underpin highly- personalised decision-making processes. Qatar; Syria; Saudi Arabia; Syrian civil war; Syrian opposition; rebel groups; terrorism financing; Key words foreign policy Catar; Siria; Arabia Saudí; guerra civil siria; oposición siria; grupos rebeldes; financiación del terrorismo; política exterior Recibido: 25/9/2015. -

Expanding the Space(S)”: Thoughts on Law, Nationalism and Humanism – Following the Bishara Case1

“Expanding the Space(s)”: Thoughts on Law, Nationalism and Humanism – Following the Bishara Case1 Barak Medina and Ilan Saban In February 2006, the Supreme Court of Israel majority of members of the Arab minority ruled that Azmi Bishara, a former Member of limits the assistance it tries to extend to its Knesset (MK), should not be criminally people to the methods permitted by Israeli law: prosecuted for speeches he made several years parliamentary, legal and civil-political struggle, ago in which he praised Hezbollah for its participation in the public discourses (the success in the fight against the Israeli military Israeli, the Palestinian, the pan-Arab and the in southern Lebanon and expressed support global), material contributions to the needy for the “resistance” to the Occupation. The and so forth. Nonetheless, within the Supreme Court determined that MK Bishara’s Palestinian Arab minority there exists a range remarks fell within the immunity accorded to of views pertaining to questions that lie at the MKs with regard to “expressing a view … in heart of the conflict: What are the goals of the fulfilling his role.” The case against MK Bishara Palestinian people’s struggle? And what are the was the first in which an indictment was filed legitimate means of attaining these goals? First, 29 against an MK for expressing a political view, should the “two-state solution” be adopted and and therefore the ruling was very important settled for? Or should there also be an assertive for determining both the scope of the material aspiration for a comprehensive realization of immunity enjoyed by MKs and the protection the right of return of the 1948 refugees and of free speech in general. -

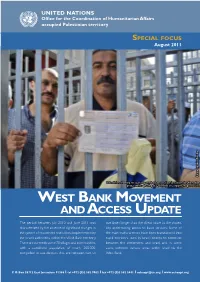

West Bank Movement Andaccess Update

UNITED NATIONS Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory SPECIAL FOCUS August 2011 Photo by John Torday John Photo by Palestinian showing his special permit to access East Jerusalem for Ramadan prayer, while queuing at Qalandiya checkpoint, August 2010. WEST BANK MOVEMENT AND ACCESS UPDATE The period between July 2010 and June 2011 was five times longer than the direct route to the closest characterized by the absence of significant changes in city, undermining access to basic services. Some of the system of movement restrictions implemented by the main traffic arteries have been transformed into the Israeli authorities within the West Bank territory. rapid ‘corridors’ used by Israeli citizens to commute There are currently some 70 villages and communities, between the settlements and Israel, and, in some with a combined population of nearly 200,000, cases, between various areas within Israel via the compelled to use detours that are between two to West Bank. P. O. Box 38712 East Jerusalem 91386 l tel +972 (0)2 582 9962 l fax +972 (0)2 582 5841 l [email protected] l www.ochaopt.org AUGUST 2011 1 UN OCHA oPt EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The period between July 2010 and June 2011 Jerusalem. Those who obtained an entry permit, was characterized by the absence of significant were limited to using four of the 16 checkpoints along changes in the system of movement restrictions the Barrier. Overcrowding, along with the multiple implemented by the Israeli authorities within the layers of checks and security procedures at these West Bank territory to address security concerns. -

Bernard Sabella, Bethlehem University, Palestine COMPARING PALESTINIAN CHRISTIANS on SOCIETY and POLITICS: CONTEXT and RELIGION

Bernard Sabella, Bethlehem University, Palestine COMPARING PALESTINIAN CHRISTIANS ON SOCIETY AND POLITICS: CONTEXT AND RELIGION IN ISRAEL AND PALESTINE Palestinian Christians, both in the Palestinian Territories (Palestine) and in Israel, number close to 180,000 altogether. Close to 50,000 of them live in the Palestinian Territories while roughly 130,000 live in Israel. In both cases, Christian Palestinians make up less than 2 percent of the overall population. In Israel, Christians make up 11% of the Arab population of over one million while in Palestine the Christians make up less than two percent (1.7%) of the entire population of three million. (1). In 1995 a survey of a national sample of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza on attitudes to society, politics and economics was conducted. It included surveying a group of 340 Christians from different localities in the West Bank and Gaza. (2). This survey provided a basis for comparing attitudes of Christians to those of their Muslim compatriots. In March 2000, a survey was conducted for the purpose of comparing the attitudes of Palestinian Christians in both Palestine and Israel. The same questionnaire was used, except for some modifications, in both the 1995 and 2000 surveys. (3). While the two surveys do not add up to a longitudinal study they, nevertheless, provide a basis to compare between two samples of Palestinian Christians in Palestine in 1995 and 2000 and between Palestinian Christians in Palestine and Israel for the year 2000. The responses of Muslim Palestinians in the 1995 survey also provide an opportunity to compare their responses with those of Christians in Israel and Palestine. -

A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Map .................................................................................................................................. i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions of Apartheid and Persecution ................................................................................. -

The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: a Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2014 The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: A Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel Samira Abunemeh University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Abunemeh, Samira, "The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: A Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel" (2014). Honors Theses. 816. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/816 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: A Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel ©2014 By Samira N. Abunemeh A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2014 Approved: Dr. Miguel Centellas Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen Reader: Dr. Vivian Ibrahim i Abstract The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: A Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel Israeli Arab political parties are observed to determine if these ethnic political parties are successful in Israel. A brief explanation of four Israeli Arab political parties, Hadash, Arab Democratic Party, Balad, and United Arab List, is given as well as a brief description of Israeli history and the Israeli political system. -

Ibn Rushd Fund for Freedom of Thought to Azmi Bishara

Press Release Ibn Rushd Fund for Freedom of Thought to Azmi Bishara The Ibn Rushd Fund for Freedom of Thought awards its prize this year to Dr. Azmi Bishara, an Arab member of the Israeli Knesset. The prize, awarded for special contributions to freedom of speech and democracy in the Arab World, will be presented on Saturday 14th December 2002 in the German capital Berlin. The Ibn-Rushd Fund, named after the philosopher Ibn Rushd (1126-1198, a.k.a. Averroes), supports freedom of speech and democracy in the Arab World by awarding this prize. The thematic focus varies annually: so far, people from the fields of journalism, women's rights and humanities were honoured. This year, the prize will be awarded to an Arab personality who has shown special commitment to promoting democracy as a member of parliament. An independent jury elected Dr. Azmi Bishara. The Palestinian intellectual, born in Nazareth in 1956, is an Israeli citizen. Since 1996, he has been a member of the Knesset. Bishara started to be engaged in political activities already as a high school student; as a university student, he co-founded the Union of Arab Students, the first political organisation of this kind in Israel. From 1980 to 1985, he studied Philosophy and Political Science at the Humboldt-University in Berlin In Ramallah, West Bank, he co-founded the Institute for Democracy and was involved in publishing many important studies in the field of research on democracy. From 1986 to 1996 held a chair for Cultural Sciences, Philosophy and Political Theory at Bir Zeit University near Ramallah, West Bank. -

Remarks by the Humanitarian Coordinator, Mr. James W. Rawley 10 Years Since the International Court of Justice (ICJ) Advisory

Remarks by the Humanitarian Coordinator, Mr. James W. Rawley 10 Years since the International Court of Justice (ICJ) Advisory Opinion on the Wall Delivered at an event of the Humanitarian Country Team in the oPt, Al Walaja, Bethlehem Governorate, 8 July 2014 Good evening. I would like to begin by thanking you all for joining me here this evening for this important event. My gratitude goes to the Humanitarian Country Team, and in particular UNRWA, for organizing this event. And our warm thanks to the Head of the Al Walaja Village Council and the people of Al Walaja for welcoming us to their community. We are here this evening, in a collective show of support for the community of Al Walaja and those like it elsewhere in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, that are impacted by the Barrier. Tomorrow marks the 10 th anniversary of the advisory opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory by the International Court of Justice, the ICJ, the world’s highest court. The ICJ stated that where the route of the Barrier is built inside the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, it violates both applicable international humanitarian law and international human rights instruments. The Court also called on Israel to cease construction of the Barrier ‘including in and around East Jerusalem and I quote: ‘to dismantle the sections already completed and to make reparations for the ‘requisition and destruction of homes, businesses and agricultural holdings’ and ‘to return the land, orchards, olive groves, and other immovable property seized.’ Of course, Israel has the right and duty to ensure the safety and security of its citizens. -

Forgotten Palestinians

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 THE FORGOTTEN PALESTINIANS 10 1 2 3 4 5 6x 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 36x 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 36x 1 2 3 4 5 THE FORGOTTEN 6 PALESTINIANS 7 8 A History of the Palestinians in Israel 9 10 1 2 3 Ilan Pappé 4 5 6x 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS 5 NEW HAVEN AND LONDON 36x 1 In memory of the thirteen Palestinian citizens who were shot dead by the 2 Israeli police in October 2000 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 Copyright © 2011 Ilan Pappé 6 The right of Ilan Pappé to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by 7 him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 8 All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright 9 Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from 20 the publishers. 1 For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, 2 please contact: U.S. -

Area a Area B Area C Israeli Settlements the Separation Wall, Implemented the Separation Wall, Under Construction Dead Sea Jorda

Area A Area B Area C Israeli Settlements The Separation Wall, Implemented The Separation Wall, Under Construction Dead Sea Jordan River Natuar Reserv Area C embodies Palestine: terraced hills with olive groves where shepherds wander with their flocks and Special issue ghazal feed on misty mornings; striking wadis where foxes and mountain goats roam; the dry, rolling desert hills and green oases of al-ghor, the Jordan valley Area C that is less and less accessible to Palestinians; the disappearing Dead Sea where Palestinians no longer feel welcome to swim. Area C comprises sixty-one percent of the West Bank and is crucial for a viable Palestinian State. Connecting Palestine’s cities and villages, 4 Sustainable Urban Development in feeding its citizens, containing a wealth of natural and economic resources, the State of Palestine: An Opportunity housing immeasurable heritage and archeological treasures, it is among the most Interrupted beautiful places in the world - but not under Palestinian control and thus, as of yet, 6 MDGs to SDGs as a viable resource mostly untapped. In Area C, check points and the Separation 10 Area C of the West Bank: Strategic Wall restrict movement and access, which impacts livelihoods and restrains the Importance and Development Prospects entire economy; here the denial of building permits and house demolitions are as much a part of daily life as the uprooting of olive groves and the prevention of 18 International Experts Call for Fundamental Area A farmers from cultivating their fields and orchards. But Area C is also where the Area B Changes in Israel’s Approach to Planning Area C Israeli Settlements creative mind of Palestinians has found ingenious ways of showing resilience and The Segregation Wall, Existing and Development in Area C The Segregation Wall, Under Construction Dead Sea developing strategies for survival and development and in this issue you can read Jordan River 24 National Strategies for Area C Natuar Reserv about some of these.