Amateur Telescope Making and Astronomical Observation at the Adler Planetarium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCO Journal October 05.Pmd

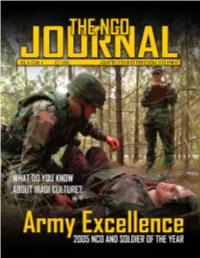

VOL: 14, ISSUE: 4 OCT 2005 A QUARTERLY FORUM FOR PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Soldiers in a Humvee search for people wishing to be rescued from Hurricane Katrina floodwaters in downtown New Orleans. Photo courtesy of www.army.mil. by Staff Sgt. Jacob N. Bailey INSIDE“ ON POINT 2-3 SMA COMMENTS IRAQI CULTURE: PRICELESS Tell the Army story with pride. They say “When in Rome, do 4-7 NEWS U CAN USE as the Romans.” But what do you know about Iraqi culture? The Army is doing its best to LEADERSHIP ensure Soldiers know how to “ manuever as better ambassa- dors in Iraq. DIVORCE: DOMESTIC ENEMY Staff Sgt. Krishna M. Gamble 18-23 National media has covered it, researchers have studied it and the sad fact is Soldiers are ON THE COVER: living it. What can you as Spc. Eric an NCO do to help? Przybylski, U.S. Dave Crozier 8-11 Army Pacific Command Soldier of the Year, evaluates NCO AND SOLDIER OF THE YEAR a casualty while he Each year the Army’s best himself is evaluated NCOs and Soldiers gather to during the 2005 NCO compete for the title. Find out and Soldier of the who the competitors are and Year competition more about the event that held at Fort Lee, Va. PHOTO BY: Dave Crozier embodies the Warrior Ethos. Sgt. Maj. Lisa Hunter 12-17 TRAINING“ ALIBIS NCO NET 24-27 LETTERS It’s not a hammer, but it can Is Detriot a terrorist haven? Is Bart fit perfectly in a leader’s Simpson a PsyOps operative? What’s toolbox. -

The Hummel Planetarium Experience

THE HUMMEL PLANETARIUM | EXPERIENCE About us: The Arnim D. Hummel Planetarium has been nestled on the south side of Eastern Kentucky University’s campus since 1988. Since then, we have provided informal science education programs to EKU students, P-12 students, as well as the community. The main theme of our programs are seated in the fields of physics and astronomy, but recent programs have explored a myriad of STEM related topics through engaging hands on experiences. Who can visit and when? We are open to the public during select weekday afternoons and evenings (seasonal) as well as most Saturdays throughout the year. The public show schedule is pre-set, and the programs serve audiences from preschool age and up. We also welcome private reservations for groups of twenty or more Mondays through Fridays during regular business hours. Examples of groups who reserve a spot include school field trips, homeschool groups, church groups, summer camps, and many more. When booking a private reservation, your group may choose which show to watch, and request a customized star talk, if needed. What happens during a visit? Most visits to the Planetarium involve viewing a pre-recorded show which is immediately followed by a live Star Talk presentation inside of the theater. A planetarium theater is unique because the viewing area is rounded into the shape of a dome instead of a flat, two-dimensional screen. The third dimension enables you, the viewer, to become immersed in the scenes displayed on the dome. A list of the pre-recorded shows we offer is found on the next page. -

History of Astronomy Is a History of Receding Horizons.”

UNA Planetarium Image of the Month Newsletter Vol. 2. No. 9 Sept 15, 2010 We are planning to offer some exciting events this fall, including a return of the laser shows. Our Fall Laser Shows will feature images and music of Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd. The word laser is actually an acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation”. We use many devices with lasers in them, from CD players to the mouse on your desk. What many people don’t know is that there are also natural lasers in space. The lasers in space often come from molecules (groups of one or more atoms sharing electrons); we call these masers. One of the more important one is the OH In 1987, astronomers observing from Chile observed a new star in the sky. This maser, formed by an oxygen and hydrogen exploding star, called a supernova, blazed away as the first supernova in several atom. The conditions in dense clouds that hundred years that was visible without a telescope. Ever since the Hubble Space form stars supply the requirements for telescope has been observing the ejecta of the explosion traveling through its host these masers. Radio astronomers study galaxy, called the Large Magellanic Cloud. This recent image of the exploding star these masers coming and going in these shows a 6-trillion mile diameter gas ring ejected from the star thousands of years dense clouds and even rotating around in before the explosion. Stars that will explode become unstable and lose mass into disks near their stars. This gives space, resulting in such rings. -

Sun, Moon, and Stars

Teacher's Guide for: Sun, Moon, and Stars OBJECTIVES: To introduce the planetarium and the night sky to the young learner. To determine what things we receive from the Sun. To see that the other stars are like our Sun, but farther away. To observe why the Moon appears to change shape and "visit" the Moon to see how it is different from the Earth. To observe the Earth from space and see that it really moves, despite the fact it looks like the Sun and stars are moving. This show conforms to the following Illinois state science standards: 12.F.1a, 12.F.1b, 12.F.2a, 12.F.2b, 12.F.2c, 12.F.3a, 12.F.3b. Next Generation Science Standards: 1.ESS1.1, 5PS2.1 BRIEF SHOW DESCRIPTION: "Sun, Moon, & Stars" is a live show for the youngest stargazers. We do a lot of pretending in the show, first by seeing what the Sun might look like both up close and from far away, and then taking an imaginary adventure to the Moon. We see the changing Moon in the sky and see how the stars in the sky make strange shapes when you connect them together. The planets can be inserted at the request of the instructor. PRE-VISIT ACTIVITIES/TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION: For the young ones, just being in the planetarium is a different experience they should "prepare" for. Discuss what it's like in a movie theater with the lights low. That's how we introduce the place. The screen goes all the way around though! Discuss the importance of the Sun. -

The Planetarium Environment by Kevin Scott the Experience of A

The Planetarium Environment by Kevin Scott The experience of a planetarium audience and staff is greatly affected by the basic physical infrastructure of a planetarium. Attention to detail in this realm is vital to a new planetarium construction project. Electrical Power Local building codes will provide a baseline for your particular power scheme and a licensed electrical engineer will handle much of the design work. Even so, it’s probably a good idea to be involved with the design process and familiarize yourself with the electrical requirements of your theater. Your interpretation of the space and production philosophy will dictate many aspects of the electrical layout and capacity. Every planetarium will have some form of star projector, and quite often there will be other unique equipment with special electrical requirements including laser systems, lighting instruments, projector lifts, and high concentrations of audio-visual equipment. Conduits and raceways for all of these devices will have to be mapped out. A spacious electrical room will make it easy to cleanly route power and control wiring throughout the planetarium. This master control area should be centrally located, perhaps beneath the theater to avoid any noise problems from equipment fans or lighting dimmers. A raised floor is an added luxury, but can make equipment installation and maintenance a breeze. Your electrical contractor will probably provide raceways for any automation control wiring. These control signals are mostly low-voltage and will need to be housed in raceways and conduits separate from power delivery. Keep in mind that you’ll want to have easy access to your low-voltage raceways for future equipment additions and upgrades. -

List of Participants

United Nations E/C.20/2017/INF/2/Rev.1 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General Date: 14 September 2017 Original: English ex Seventh Session of the UN Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information Management (UN-GGIM) New York, 2-4 August 2017 List of Participants Co-Chairs Mr. Timothy Trainor (United States) Mr. Li Pengde (China) Ms. Dorine Burmanje (Netherlands) Rapporteur Mr. Fernand Guy Isseri (Cameroon) 17-16037X (E) 140917 *1716037* E/C.20/2017/INF/2/Rev.1 Member States I. Algeria 1. Mr. Hamid Oukaci, Secretary General, National Geospatial Information Council (CNIG) II. Antigua and Barbuda 2. Mr. Andrew Nurse, Survey and Mapping Division in the Ministry of Agriculture, Lands, Fisheries and Barbuda Affairs III. Argentina 3. Embajador Martín Garcia Moritan, Jefe de Delegación, Representante Permanente de la República Argentina ante las Naciones Unidas 4. Ministro Plenipotenciario Gabriela Martinic, Representante Permanente Alterna de la República Argentina ante las Naciones Unidas 5. Agrim. Sergio Cimbaro, Presidente del Instituto Geográfico Nacional, Ministerio de Defensa 6. Agrim. Diego Piñón, Director de Geodesia del Instituto Geográfico Nacional, Ministerio de Defensa 7. Secretario de Embajada Tomas Pico, Misión Permanente de la República Argentina ante las Naciones Unidas 8. Secretario de Embajada Guido Crilchuk, Misión Permanente de la República Argentina ante las Naciones Unidas IV. Australia 9. Dr. Stuart Minchin, Head of Delegation, Chief of Environmental Geoscience Division, Geoscience Australia 10. Ms. Caitlin Wilson, Representative, Ambassador and Permanent representative of Australia to the United Nations 11. Mr. Gary Johnston, Representative, Branch Head of Geodesy and Seismic Monitoring, Geoscience Australia 12. Mr. William Watt, Team Leader, Land Tenure and Statutory Support, Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure 13. -

The Magic of the Atwood Sphere

The magic of the Atwood Sphere Exactly a century ago, on June Dr. Jean-Michel Faidit 5, 1913, a “celestial sphere demon- Astronomical Society of France stration” by Professor Wallace W. Montpellier, France Atwood thrilled the populace of [email protected] Chicago. This machine, built to ac- commodate a dozen spectators, took up a concept popular in the eigh- teenth century: that of turning stel- lariums. The impact was consider- able. It sparked the genesis of modern planetariums, leading 10 years lat- er to an invention by Bauersfeld, engineer of the Zeiss Company, the Deutsche Museum in Munich. Since ancient times, mankind has sought to represent the sky and the stars. Two trends emerged. First, stars and constellations were easy, especially drawn on maps or globes. This was the case, for example, in Egypt with the Zodiac of Dendera or in the Greco-Ro- man world with the statue of Atlas support- ing the sky, like that of the Farnese Atlas at the National Archaeological Museum of Na- ples. But things were more complicated when it came to include the sun, moon, planets, and their apparent motions. Ingenious mecha- nisms were developed early as the Antiky- thera mechanism, found at the bottom of the Aegean Sea in 1900 and currently an exhibi- tion until July at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers in Paris. During two millennia, the human mind and ingenuity worked constantly develop- ing and combining these two approaches us- ing a variety of media: astrolabes, quadrants, armillary spheres, astronomical clocks, co- pernican orreries and celestial globes, cul- minating with the famous Coronelli globes offered to Louis XIV. -

2002 Convention Bulletin

STELLAFANE The 67th Convention of Amateur Telescope Makers on Breezy Hill in Springfield, Vermont. Friday, August 9th and Saturday, August 10th, 2002 "For it is true that astronomy, from a popular standpoint, is handicapped by the inability of the average workman to own an expensive astronomical telescope. It is also true that if an amateur starts out to build a telescope just for fun he will find, before his labors are over, that he has become seriously interested in the wonderful mechanism of our universe. And finally there is understandably the stimulus of being able to unlock the mysteries of the heavens by a tool fashioned by one's own hand." Russell W. Porter, March 1923 -- Founder of Stellafane The Stellafane Convention is a gathering of amateur telescope makers. The Convention was started in 1926 to give amateur telescope makers an opportunity to gather, to show off their creations and teach each other telescope making and mirror grinding techniques. If you have made your own telescope, we strongly encourage you to display it in the telescope fields near the Pink Clubhouse. If you wish, you can enter it in the mechanical and/or optical competition. There are also mirror grinding and telescope making demonstrations, technical lectures on telescope making and the presentation of awards for telescope design and craftsmanship. Vendor displays and the retail sale of commercial products are not permitted. For additional information please check out the home page www.stellafane.com. Enjoy the convention! PLEASE NOTE AN IMPORTANT SCHEDULE CHANGE DURING CONVENTION: The optical judging has been re- scheduled for Friday night! There will be no optical judging Saturday night unless clouds interfere with the optical competition on Friday. -

Ernest Fox Nichols

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES E R N E S T F O X N ICHOLS 1869—1924 A Biographical Memoir by E . L . NICHOLS Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1929 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. ERNEST FOX NICHOLS BY R. L. NICHOLS One winter evening in the year 1885 the present writer lec- tured at the Kansas Agricultural College. It was an illustrated talk on experimental physics to students who thronged the col- lege chapel. Some three years later, when that event had passed into the realm of things half forgotten, two young men appeared at the physical laboratory of Cornell University. They ex- plained that they had been in the audience at Manhattan on the occasion just mentioned and had been so strongly interested that they had decided then and there to devote themselves to the study of physics. Now, having finished their undergrad- uate course they had come east to enter our graduate school. One of these two Kansas boys, both of whom were then quite unknown to the writer, was Ernest Fox Nichols. Nichols was born in Leavenworth, Kansas, on June 1. 1869. He was soon left parentless, a lonely boy but with means to help him obtain an education, and went to live with an uncle and aunt, Mr. and Mrs. Fox, of Manhattan, in that State. He was tall, fair, clear-eyed, of open countenance and winning smile, and there was that about him which once seen was never forgotten. -

The Seth Thomas Sidereal Clock, Now Located in the UH Institute for Astronomy Library

The Seth Thomas sidereal clock, now located in the UH Institute for Astronomy library. The large hand reads minutes, upper small hand, hours, and the lower small hand, seconds, of sidereal time, or time by the stars, as opposed to solar time. On the right is seen one of the two weights that drive the clock. They must be wound to the top once a week. A close up of the clock’s nameplate shows that it is clock no. 13. The University of Hawai`i Observatory, Kaimuki, 1910 to 1958, as seen in 1917 by E.H. Bryan, Jr. Soon after the turn of the century an astronomical event of major scientic as well as popular interest stirred the citizens of Honolulu: the predicted appearance of Halley’s Comet in 1910. By public subscription an observatory was built on Ocean View Drive in Kaimuki, which was then a suburb of Honolulu in the vicinity of Diamond Head. A civic group known as the Kaimuki Improvement Association donated the site, which oered an excellent view of the sky. A six-inch refractor manufactured by Queen and Company of Philadel- phia was placed in the observatory along with a very ne Seth Thomas sidereal clock and a three-inch meridian passage telescope. The observatory was operated by the edgling College of Hawai‘i, later to become the University of Hawai‘i. The public purpose of the Kaimuki Observatory was served and Halley’s Cometwas observed. But, unfortunately, the optics of the telescope were not good enough for serious scientic work. From “Origins of Astronomy in Hawai’i,” by Walter Steiger, Professor Emeritus, University of Hawai’i The Seth Thomas sidereal clock is now located in the UH Institute for Astronomy Library. -

PLANETARIUM SHOWS Field Trip Experiences in the Willard Smith Planetarium Allow Students to Explore Space Science Concepts in a Live, Interactive Presentation

FIELD TRIP EXPERIENCES PLANETARIUM SHOWS Field trip experiences in the Willard Smith Planetarium allow students to explore space science concepts in a live, interactive presentation. Ask about cusomizing the show to meet your education goals! Preschool All Stars Jupiter and its Moons Designed for our youngest learners, this show is an This show focuses on the mission of the Juno opportunity for children of all ages to be introduced spacecraft. Students learn about the solutions devised to the wonders of astronomy. Students will practice for challenges facing the mission and use observational pattern recognition while discovering their first skills to compare Jupiter’s moons to the earth. constellations. 15 minutes. Pre–K 30 minutes. Grades 6–12 The Sky Tonight Let’s Explore Light Focusing on naked-eye astronomy, The Sky Tonight In Let’s Explore Light, students learn about the nature shows students how the stars can be used for of light and the processes used by scientists who study navigation and how to find constellations and Planets. light. They use spectroscopy to identify the building We talk about current visible events and also look blocks of stars, and discover how spectroscopy has at some objects only visible through a telescope. helped us understand the nature of the universe. 30 minutes. Grades K–12 30 minutes. Grades 6–12 The Planets NEW! Earth Pole to Pole Fly through the Rings of Saturn and see the largest In this planetary science live presentation we explore volcano on Mars as we visit the planets in our solar the northern and southern polar regions of the planet system. -

Web Suppliers of Telescope Building Parts and Materials

Appendix I Web Suppliers of Telescope Building Parts and Materials No endorsement or recommendation is provided or implied. The organizations listed are here because they were found in other such lists or advertisements or were personally known to someone. Those for whom e-mail addresses were available were notified that they would be listed. Those for whom there were no e-mail addresses or whose e-mail was not deliverable were sent regular letters with the same information. If there was no response to notification, the listing was removed. Quite a few listed organizations submitted additions or changes to their list of products. References to items specific to astrophotography and to Dobsonians were, for the most part, avoided. Likewise, references to subjects other than building telescopes, such as star charts, were avoided. If you are searching for some particular item or for something that will serve for a particular item you are advised to look under a variety of related categories. There is very little standardization of nomenclature in telescope design. For exam- ple, “used” usually means “buys and sells used parts and complete scopes.” Rings and mounting rings probably are overlapping categories. Diagonals, mirrors, and secondary mirrors probably all mean the same thing. Some of the listed organizations produce or distribute items useful to us telescope makers but with a much wider/different selection of clients. In dealing with them it would be useful if you are particularly clear as to the intended use. Some produce items for other industries and are set up to supply materials in large quantities.