A Musical and Production Analysis of CURTAINS by John Kander and Fred Ebb Kevin A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ARVADA CENTER PRESENTS the WHODUNIT MUSICAL COMEDY CURTAINS Featuring a Musical Score by the Legendary Team Who Brought You Chicago and Cabaret

June 18, 2013 Media contact: Melanie Mayner Box Office: 720-898-7200 [email protected] / 720-898-7276 Images are available for download at http://www.flickr.com/photos/arvadacenter/sets/72157634051301381 THE ARVADA CENTER PRESENTS THE WHODUNIT MUSICAL COMEDY CURTAINS Featuring a musical score by the legendary team who brought you Chicago and Cabaret Arvada CO - The Arvada Center will open the award winning musical, Curtains directed by Gavin Mayer on Tuesday, July 9. Curtains is written by Rupert Holmes, and is based on the original book by Peter Stone, with music by John Kander and lyrics by Fred Ebb (Chicago and Cabaret). Performances are Tuesday - Saturday at 7:30 p.m., Wednesday at 1 p.m., Saturday and Sunday at 2 p.m., through July 28. Preview performances are July 5 - 7 at 7:30 p.m. Moderated talkbacks with the cast are offered on Friday, July 19 after the 7:30 p.m. show and Wednesday, July 24 after the 1:00 p.m. show. For more information and to purchase tickets, go to http://arvadacenter.org/on-stage/curtains or call 720-898-7200. Curtains debuted on Broadway in 2007 and was nominated for eight Tony Awards, including Best Musical, Best Book and Best Original Score. As Curtains opens, the chief sleuth, Lieutenant Frank Cioffi, who harbors a secret affinity for musical theater, investigates the murder of a Broadway-bound theater company’s tremendously untalented star on opening night. Could the culprit be the hard-edged lady producer, one of the recently divorced songwriting team, the egomaniacal British director, or the seemingly sweet ingénue? Curtains will have you on the edge of your seat - laughing! In addition to director Gavin Mayer, the creative team includes David Nehls (musical director), Kitty Skillman Hilsabeck (choreographer), Brian Mallgrave (scene design), Clare Henkel (costume design), David Thomas (sound design) and Jane Spencer (light design). -

Alex Koch, Tenor Stephen Carey, Piano

presents Alex Koch, tenor Stephen Carey, piano Sunday, November 15th, 2020 7:00 PM TCU School of Music Wilkommen John Kander From Cabaret (1927-Present) Caro Mio Ben Giuseppe Giordani (1751-1798) The Juices Entwine Christopher Weiss and John de los Santos From Service Provider (1980-Present) (1981-Present) For Forever Benj Pasek and Justin Paul From Dear Evan Hansen (1985-Present) (1985-Present) Time Jeannie Miller (1996-Present) Love, Unrequited, Robs me of my Rest W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan (1836-1911) (1842-1900) Sure on this Shining Night Samuel Barber (1910-1981) Artwork by Elizabeth Gondolf Les Chemins de l’amour Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) Dance performed by Ali Honchell Freundliche Vision Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Artwork by Ian L. Mr. Koch’s portion of the recital is given in fulfillment of the requirements for Bachelor’s in Music Performance degree. Mr. Koch is a student of Professor Twyla Robinson, Dr. Corey Trahan, and Professor David Gately. The use of recording equipment or taking photographs is prohibited. Please silence all electronic devices. Wilkommen John Kander (1927 – Present) From Cabaret Based off of the 1951 play by queer playwright John Van Druten, Cabaret was written and premiered in 1966 by John Kander, Fred Ebb, and Joe Masteroff. The play by Van Druten, titled I Am a Camera, was inspired by the 1939 novel by Christopher Isherwood, Goodbye to Berlin. This novel is important in the inception of Cabaret as well as I Am a Camera, as it gives the plot, the conflict, and the characters used throughout the play and the musical. -

Cole Porter: the Social Significance of Selected Love Lyrics of the 1930S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository Cole Porter: the social significance of selected love lyrics of the 1930s by MARILYN JUNE HOLLOWAY submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject of ENGLISH at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR IA RABINOWITZ November 2010 DECLARATION i SUMMARY This dissertation examines selected love lyrics composed during the 1930s by Cole Porter, whose witty and urbane music epitomized the Golden era of American light music. These lyrics present an interesting paradox – a man who longed for his music to be accepted by the American public, yet remained indifferent to the social mores of the time. Porter offered trenchant social commentary aimed at a society restricted by social taboos and cultural conventions. The argument develops systematically through a chronological and contextual study of the influences of people and events on a man and his music. The prosodic intonation and imagistic texture of the lyrics demonstrate an intimate correlation between personality and composition which, in turn, is supported by the biographical content. KEY WORDS: Broadway, Cole Porter, early Hollywood musicals, gays and musicals, innuendo, musical comedy, social taboos, song lyrics, Tin Pan Alley, 1930 film censorship ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to thank Professor Ivan Rabinowitz, my supervisor, who has been both my mentor and an unfailing source of encouragement; Dawie Malan who was so patient in sourcing material from libraries around the world with remarkable fortitude and good humour; Dr Robin Lee who suggested the title of my dissertation; Dr Elspa Hovgaard who provided academic and helpful comment; my husband, Henry Holloway, a musicologist of world renown, who had to share me with another man for three years; and the man himself, Cole Porter, whose lyrics have thrilled, and will continue to thrill, music lovers with their sophistication and wit. -

Friends of Niagara University Theatre

Friends of Niagara University Theatre For those who love theatre at Niagara University Spring 2005 Broadway Luminary Lights Friends’ 20th Annual Gala One of Broadway’s brightest talents, exciting evening as we support the with three composer and Tony-Award winner Niagara University Theatre program major John Kander, will be the guest of honor and its students.” productions: at the 20th Annual Friends’ Gala to be Guest of honor John Kander has the held on Saturday, April 30, at the written Broadway scores for: “A Family Encores Castellani Art Museum on Niagara Affair” (1962); “Never Too Late” production University’s campus. (1962); “Flora, the Red Menace” of The gala will include a silent auction (1965); “Cabaret” (1966); “The “Chicago”; featuring a variety of items, an open bar Happy Time” (1968); “Zorba” (1968); the preceding an elegant dinner, and “70, Girls, 70” (1971); “Zorba” Donmar Niagara University Theatre (London, 1973); “Chicago” (1975); (from performance of “Flora, the Red “The Act” (1977); “And The World London) John Kander Menace,” with music by John Kander Goes Round — The Kander and Ebb production of “Cabaret”; and “Steel and lyrics by the late Fred Ebb. The Musical” (1991); “Kiss of the Spider Pier,” which Niagara University charming, bittersweet musical is based Woman” (1993); and “Steel Pier” Theatre produced in 1999. His work, on the novel “Love is Just Around the (1997). Television work includes music “The Visit,” premiered in Chicago in Corner” by Lester Atwell. The musical for “Liza with a Z” (1974); “Ole Blue 2001. He is also the recipient of The underwent a major revival in New York Eyes is Back” (Frank Sinatra); Kennedy Center Honors. -

YCH Monograph TOTAL 140527 Ts

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Transformation of The Musical: The Hybridization of Tradition and Contemporary Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1hr7f5x4 Author Hu, Yuchun Chloé Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transformation of The Musical: The Hybridization of Tradition and Contemporary A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Yu-Chun Hu 2014 Copyright by Yu-Chun Hu 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transformation of The Musical: The Hybridization of Tradition and Contemporary by Yu-Chun Hu Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Ian Krouse, Chair Music and vision are undoubtedly connected to each other despite opera and film. In opera, music is the primary element, supported by the set and costumes. The set and costumes provide a visual interpretation of the music. In film, music and sound play a supporting role. Music and sound create an ambiance in films that aid in telling the story. I consider the musical to be an equal and reciprocal balance of music and vision. More importantly, a successful musical is defined by its plot, music, and visual elements, and how well they are integrated. Observing the transformation of the musical and analyzing many different genres of concert music, I realize that each new concept of transformation always blends traditional and contemporary elements, no matter how advanced the concept is or was at the time. Through my analysis of three musicals, I shed more light on where this ii transformation may be heading and what tradition may be replaced by a new concept, and vice versa. -

November 13 – the Best of Broadway

November 13 – The Best of Broadway SOLOISTS: Bill Brassea Karen Babcock Brassea Rebecca Copley Maggie Spicer Perry Sook PROGRAM Broadway Tonight………………………………………………………………………………………………Arr. Bruce Chase People Will Say We’re in Love from Oklahoma……….…..Rodgers & Hammerstein/Robert Bennett Try to Remember from The Fantasticks…………………………………………………..Jack Elliot/Jack Schmidt Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man from Show Boat……………………………Oscar Hammerstein/Jerome Kern/ Robert Russell Bennett Gus: The Theatre Cat from Cats……………………………………….……..…Andrew Lloyd Webber/T.S. Eliot Selections from A Chorus Line…………………………………….……..Marvin Hamlisch/Arr. Robert Lowden Glitter and Be Gay from Candide…………………….………………………………………………Leonard Bernstein Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off from Shall We Dance…….…….……………………George & Ira Gershwin Impossible Dream from Man of La Mancha………………………………………….…Mitch Leigh/Joe Darion Mambo from Westside Story……………………………………………..…………………….…….Leonard Bernstein Somewhere from Westside Story……………………………………….…………………….…….Leonard Bernstein Intermission Seventy-Six Trombones from The Music Man………………………….……………………….Meredith Willson Before the Parade Passes By from Hello, Dolly!……………………………John Herman/Michael Stewart Vanilla Ice Cream from She Loves Me…………..…………....…………………….Sheldon Harnick/Jerry Bock Be a Clown from The Pirate..…………………………………..………………………………………………….Cole Porter Summer Time from Porgy & Bess………………………………………………………….………….George Gershwin Move On from Sunday in the Park with George………….……..Stephen Sondheim/Michael Starobin The Grass is Always Greener from Woman of the Year………….John Kander/Fred Ebb/Peter Stone Phantom of the Opera Overture……………………………………………………………….Andrew Lloyd Webber Music of the Night from Phantom of the Opera…….………………………………….Andrew Lloyd Webber Love Never Dies from Love Never Dies………………..…..……………………………….Andrew Lloyd Webber Over the Rainbow from The Wizard of Oz….……………………………………….Harold Arlen/E.Y. Harburg Arr. Mark Hayes REHEARSALS: Mon., Oct. 17 7 p.m. -

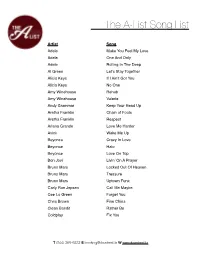

The A-List Songlist 2015

The A-List Song List Artist Song Adele Make You Feel My Love Adele One And Only Adele Rolling In The Deep Al Green Let’s Stay Together Alicia Keys If I Ain’t Got You Alicia Keys No One Amy Winehouse Rehab Amy Winehouse Valerie Andy Grammar Keep Your Head Up Aretha Franklin Chain of Fools Aretha Franklin Respect Ariana Grande Love Me Harder Avicii Wake Me Up Beyonce Crazy In Love Beyonce Halo Beyonce Love On Top Bon Jovi Livin’ On A Prayer Bruno Mars Locked Out Of Heaven Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe Cee Lo Green Forget You Chris Brown Fine China Clean Bandit Rather Be Coldplay Fix You T (844) 369-6232 E [email protected] W www.downbeat.la The A-List Song List Artist Song Coldplay Viva La Vida Corinne Bailey Rae Put You Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Daft Punk Lose Yourself To Dance David Guetta Ft. Sia Titanium Destiny’s Child Say My Name Earth, Wind, and Fire Let’s Groove Earth, Wind, And Fire September Ed Sheeren Thinking Out Loud Ellie Golding Love Me Like You Do Ellie Golding Need Your Love Emeli Sande Next To Me Estelle American Boy Etta James At Last Frank Sinatra Fly Me To The Moon Frank Valli December ’63 (Oh What A Night) Gnarls Barkley Crazy Guns ‘N’ Roses Sweet Child Of Mine Jackson 5 ABC Jackson 5 I Want You Back Jason Mraz I’m Yours Jay Z & Alicia Keys Empire State Of Mind Jazz Standard Summertime Jessie J Domino John Legend All Of Me T (844) 369-6232 E [email protected] W www.downbeat.la The A-List Song List Artist Song John Legend Ordinary People Journey Crazy Little Thing Called Love Journey Don’t Stop Believin Justin Timberlake Señorita Justin Timberlake Sexyback Justin Timberlake Suit & Tie Katy Perry California Girls Katy Perry Firework Katy Perry Roar Katy Perry Teenage Dream Kenny Loggins Footloose Lady Gaga Just Dance Lorde Royals Maroon 5 Moves Like Jagger Maroon 5 Sugar Maroon 5 Sunday Morning Marvin Gaye What’s Going On Marvin Gaye Ft. -

An Afternoon on Broadway Marks the Beginning of the Band’S 33Rd Season

Purpose and History The Community Band of Brevard exists to educate its members, to entertain its audiences, and to serve its community. Our musical director is Mr. Marion Scott. Mr. Scott formed the Band in 1985 to provide a performance outlet for adult musicians in the area. Our membership, currently numbering about 80, includes people of all ages representing many occupations. Most of our concerts have a specific theme upon which the music focuses. Those themes have often led us to include exceedingly difficult works, which we willingly do, and to include special guest artists. The Band gives several concerts throughout the year. Our concerts include many diverse musical genres, composers, and often previously unpublished works for band. Each program is planned to please a variety of musical tastes. If you would like more information about the Band, or wish to join, send us a message to [email protected] or contact David Scarborough at (321) 338-6210. Like us on Facebook at Community Band of Brevard and visit our Web site at http://www.CommunityBandOfBrevard.com. CBOB’S FL DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE & CONSUMER SERVICES REGISTRATION NUMBER IS CH35170. A COPY OF THE OFFICIAL REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE DIVISION OF CONSUMER SERVICES BY CALLING TOLL-FREE (800- 435-7352) WITHIN THE STATE. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT, APPROVAL, OR RECOMMENDATION BY THE STATE. Board of Directors Conductor .............................................................. Marion Scott Chairman ...................................................... -

The A-List Songlist 2017

The A-List Song List Song Artist 24K Magic Bruno Mars A Thousand Years Christina Perri Adorn Miguel Ain't No Mountain High Marvin Gaye Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud to Beg The Temptations Alcoholic Common Kings All My LIfe KC and Jojo All of Me John Legend All Star Smash Mouth Always Be My Baby Mariah Carey American Girl Tom Petty At Last Etta James Baby One More Time Britney Spears Bad Girls Donna Summer Bennie and the Jets Elton John Billie Jean Michael Jackson Blame It On the Boogie Jackson 5 Bless The Broken Road Rascal Flatts Blue Bossa Kenny Dorham Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie A Taste of Honey Boondocks Little Big Town Boot Scootin' Boogie Brooks & Dunn Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison T (844) 369-6232 E [email protected] W www.downbeat.la The A-List Song List Song Artist Bye Bye Bye *NSYNC Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Girls Katy Perry California Love 2PAC Can't Feel My Face The Weeknd Can't Help Falling in Love Elvis Presley Can't Stop the Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Take My Eyes Off You Lauryn Hill Cantaloupe Island Herbie Hancock Chain of Fools Aretha Franklin Chameleon Herbie Hancock Cheerleader Omi Closer Chainsmokers Come Together The Beatles Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Country Girl (Shake It For Me) Luke Bryan Crazy Gnarles Barkley Crazy In Love Beyonce Crazy Little Thing Called Love Queen Crazy Love Brian McKnight Dancing In The Moonlight King Harvest Diamonds Rihanna Do You Love me The Contours Domino Jessie J Don't Know Why Norah Jones T (844) 369-6232 E [email protected] W www.downbeat.la -

SUZANNE AGINS 77 East 12Th Street, #2C, New York, NY 10003 [email protected] ~ (646) 245-9306 ~

SUZANNE AGINS 77 East 12th Street, #2C, New York, NY 10003 [email protected] ~ (646) 245-9306 ~ www.suzanneagins.com Directing - NYC & Regional (* DENOTES WORLD PREMIERE, ‡ DENOTES MUSICAL) In the Heights ‡ Lin-Manuel Miranda / Quiara Alegria Hudes Hangar Theater The Club (workshop production) Amy Fox Ensemble Studio Theatre Radiance * Cusi Cram LAByrinth Theater Company Radiance (workshop production) Cusi Cram Cino Nights, Rising Phoenix Repertory 8th Annual NYC 1MPF Rachel Axler, Melissa James Gibson, Rajiv Joseph, Primary Stages Ellen McLaughlin, Julian Sheppard, Daniel Goldfarb Fallen Angels Noel Coward Dorset Theatre Festival Alligator (workshop) Hilary Bettis Eugene O’Neill National Playwrights Conference The Burden of Not Having a Tail (workshop) Carrie Barrett Eugene O’Neill National Playwrights Conference Jailbait * Deirdre O’Connor Cherry Lane Theater Jailbait (workshop production) Deirdre O’Connor Cherry Lane Mentor Project Monstrosity (workshop) Lucy Thurber Williamstown Theatre Festival Lascivious Something (workshop production) Sheila Callaghan Cherry Lane Mentor Project Lucy and the Conquest * Cusi Cram Williamstown Theatre Festival Wing It * ‡ (inspired by Aristophanes’ The Birds) book/lyrics: Gordon Cox, music: Kris Kukul Williamstown Theatre Festival Dash Dexter ‡ (workshop) book/lyrics: Gordon Cox, music: Kris Kukul Fang Theatre Company The Secret Narrative of the Phone Book * Gordon Cox Kraine Theater / Horsetrade Productions Soho Shorts Matt Hoverman Soho Playhouse The Student * Matt Hoverman Samuel French Short -

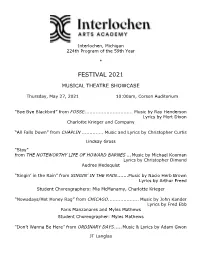

PDF Program Download

Interlochen, Michigan 224th Program of the 59th Year * FESTIVAL 2021 MUSICAL THEATRE SHOWCASE Thursday, May 27, 2021 10:00am, Corson Auditorium “Bye Bye Blackbird” from FOSSE ............................... Music by Ray Henderson Lyrics by Mort Dixon Charlotte Krieger and Company “All Falls Down” from CHAPLIN .............. Music and Lyrics by Christopher Curtis Lindsay Gross “Stay” from THE NOTEWORTHY LIFE OF HOWARD BARNES ... Music by Michael Kooman Lyrics by Christopher Dimond Audree Hedequist “Singin’ in the Rain” from SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN ....... Music by Nacio Herb Brown Lyrics by Arthur Freed Student Choreographers: Mia McManamy, Charlotte Krieger “Nowadays/Hot Honey Rag” from CHICAGO .................... Music by John Kander Lyrics by Fred Ebb Paris Manzanares and Myles Mathews Student Choreographer: Myles Mathews “Don’t Wanna Be Here” from ORDINARY DAYS ..... Music & Lyrics by Adam Gwon JT Langlas “No One Else” from NATASHA, PIERRE AND THE GREAT COMET OF 1812 ......... Music and Lyrics by Dave Malloy Mia McManamy “Run, Freedom, Run” from URINETOWN ...................... Music by Mark Hollmann Lyrics by Mark Hollmann and Greg Kotis Scout Carter and Company “Forget About the Boy” from THOROUGHLY MODERN MILLIE ........................... Music by Jeanine Tesori Lyrics by Dick Scanlan Hannah Bank and Company Student Choreographer: Nicole Pellegrin “She Used to Be Mine” from WAITRESS ........ Music and Lyrics by Sara Bareilles Caroline Bowers “Change” from A NEW BRAIN ......................... Music and Lyrics by William Finn Shea Grande “We Both Reached for the Gun” from CHICAGO .............. Music by John Kander Lyrics by Fred Ebb Theo Gyra and Company Student Choreographer: Myles Mathews “Love is an Open Door” from FROZEN ............ Music & Lyrics by Kristen Anderson-Lopez & Robert Lopez Charlotte Krieger and Daniel Rosales “Being Alive” from COMPANY ............... -

Issue 2 2015|2016 SEASON

2015|2016 SEASON Issue 2 TABLE OF Dear Friend, It has finally happened. It always CONTENTS seemed that Kiss Me, Kate was the perfect show for the Shakespeare 1 Title page Theatre Company to produce. It is Recipient of the 2012 Regional Theatre Tony Award® one of the wittiest musical comedies 3 Cast in the canon, featuring the finest Artistic Director Michael Kahn score Cole Porter ever wrote, Executive Director Chris Jennings 4 Director’s Word stuffed to the brim with songs romantic, hilarious, and sometimes both. It is also, not coincidentally, a landmark 8 Story, Musical Numbers adaptation of Shakespeare, a work that no less a critic than and Orchestra W.H. Auden considered greater than Shakespeare’s own The Taming of the Shrew. 9 Music Director’s Word All I can say to the multitudes who have suggested this show to me over the past 29 years is that we waited 13 About the Authors until the moment was right: until we knew we could do a production that could satisfy us, with a cast that could 14 The Taming of work wonders with this material. music and lyrics by Cole Porter the Screwball book by Samuel and Bella Spewack Also, of course, with the right director. He doesn’t need 18 It Takes Two any introduction, having directed two classic (and Performances begin November 17, 2015 classically influenced) musicals for us—2013–2014’s Opening Night November 23, 2015 (Times Two) award-winning staging of A Funny Thing Happened on the Sidney Harman Hall Way to the Forum and 2014–2015’s equally magnificent 24 Mapping the Play Man of La Mancha—but nonetheless I am very happy that STC Associate Artistic Director Alan Paul has agreed to Director Fight Director 26 Kiss Me, Kate and complete his trifecta with Kiss Me, Kate.