Psalm 108 and the Quest for Closure to the Exile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psalm 60-64 Monday 22Nd June - Psalm 60

Daily Devotions in the Psalms Psalm 60-64 Monday 22nd June - Psalm 60 For the director of music. To the tune of “The 6 God has spoken from his sanctuary: Lily of the Covenant.” A miktam of David. For “In triumph I will parcel out Shechem teaching. When he fought Aram Naharaim and and measure off the Valley of Sukkoth. Aram Zobah, and when Joab returned and 7 Gilead is mine, and Manasseh is mine; struck down twelve thousand Edomites in the Ephraim is my helmet, Valley of Salt. Judah is my scepter. 8 Moab is my washbasin, You have rejected us, God, and burst upon us; on Edom I toss my sandal; you have been angry—now restore us! over Philistia I shout in triumph.” 2 You have shaken the land and torn it open; 9 Who will bring me to the fortified city? mend its fractures, for it is quaking. Who will lead me to Edom? 3 You have shown your people desperate times; 10 Is it not you, God, you who have now rejected you have given us wine that makes us stagger. us 4 But for those who fear you, you have raised a and no longer go out with our armies? banner 11 Give us aid against the enemy, to be unfurled against the bow. for human help is worthless. 5 Save us and help us with your right hand, 12 With God we will gain the victory, that those you love may be delivered. and he will trample down our enemies. It seems that this Psalm is written against the backdrop of Israel’s army being defeated in the final days of Saul’s reign. -

80 Days in the Psalms (Summer 2016)

80 Days in the Psalms (Summer 2016) June 16 Psalm 1, 2 July 6 Psalm 40, 41 July 26 Psalm 80, 81 August 15 Psalm 119 June 17 Psalm 3, 4 July 7 Psalm 42, 43 July 27 Psalm 82, 83 August 16 Psalm 119 June 18 Psalm 5, 6 July 8 Psalm 44, 45 July 28 Psalm 84, 85 August 17 Psalm 119 June 19 Psalm 7, 8 July 9 Psalm 46, 47 July 29 Psalm 86, 87 August 18 Psalm 119 June 20 Psalm 9, 10 July 10 Psalm 48, 49 July 30 Psalm 88, 89 August 19 Psalm 120, 121 June 21 Psalm 11, 12 July 11 Psalm 50, 51 July 31 Psalm 90, 91 August 20 Psalm 122, 123 June 22 Psalm 13, 14 July 12 Psalm 52, 53 August 1 Psalm 92, 93 August 21 Psalm 124, 125 June 23 Psalm 15, 16 July 13 Psalm 54, 55 August 2 Psalm 94, 95 August 22 Psalm 126, 127 June 24 Psalm 17, 18 July 14 Psalm 56, 57 August 3 Psalm 96, 97 August 23 Psalm 128, 129 June 25 Psalm 19, 20 July 15 Psalm 58, 59 August 4 Psalm 98, 99 August 24 Psalm 130, 131 June 26 Psalm 21, 22 July 16 Psalm 60, 61 August 5 Psalm 100, 101 August 25 Psalm 132, 133 June 27 Psalm 23, 23 July 17 Psalm 62, 63 August 6 Psalm 102, 103 August 26 Psalm 134, 135 June 28 Psalm 24, 25 July 18 Psalm 64, 65 August 7 Psalm 104, 105 August 27 Psalm 136, 137 June 29 Psalm 26, 27 July 19 Psalm 66, 67 August 8 Psalm 106, 107 August 28 Psalm 138, 139 June 30 Psalm 28, 29 July 20 Psalm 68, 69 August 9 Psalm 108, 109 August 29 Psalm 140, 141 July 1 Psalm 30, 31 July 21 Psalm 70, 71 August 10 Psalm 110, 111 August 30 Psalm 142, 143 July 2 Psalm 32, 33 July 22 Psalm 72, 73 August 11 Psalm 112, 113 August 31 Psalm 144, 145 July 3 Psalm 34, 35 July 23 Psalm 74, 75 August 12 Psalm 114, 115 September 1 Psalm 146, 147 July 4 Psalm 36, 37 July 24 Psalm 76, 77 August 13 Psalm 116, 117 September 2 Psalm 148, 149 July 5 Psalm 38, 39 July 25 Psalm 78, 79 August 14 Psalm 118 September 3 Psalm 150 How to use this Psalms reading guide: • Read consistently, but it’s okay if you get behind. -

Psalms Commentary

I YOU CAN UNDERSTAND THE BIBLE PSALMS: THE HYMNAL OF ISRAEL BOOK I BOB UTLEY PROFESSOR OF HERMENEUTICS (BIBLE INTERPRETATION) STUDY GUIDE COMMENTARY SERIES OLD TESTAMENT, VOL. 9B BIBLE LESSONS INTERNATIONAL MARSHALL, TEXAS 2012 www.BibleLessonsIntl.com www.freebiblecommentary.org Copyright ©2012 by Bible Lessons International, Marshall, Texas All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any way or by any means without the written permission of the publisher. Bible Lessons International P. O. Box 1289 Marshall, TX 75671-1289 1-800-785-1005 ISBN 978-1-892691-37-8 The primary biblical text used in this commentary is: New American Standard Bible (Update, 1995) Copyright ©1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation P. O. Box 2279 La Habra, CA 90632-2279 The paragraph divisions and summary captions as well as selected phrases are from: 1. The New King James Version, Copyright ©1979, 1980, 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. 2. The New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, Copyright ©1989 by the Division of Christian Education of National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U. S. A. Used by permission. All rights reserved. 3. Today’s English Version is used by permission of the copyright owner, The American Bible Society, ©1966, 1971. Used by permission. All rights reserved. 4. The New Jerusalem Bible, copyright ©1990 by Darton, Longman & Todd, Ltd. and Doubleday, a division of Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. www.freebiblecommentary.org The New American Standard Bible Update — 1995 Easier to read: } Passages with Old English “thee’s” and “thou’s” etc. -

Daily Lectionary This Outline Is a Devotional Reading Plan That Covers the Entire Sacred Scriptures Each Year

Daily Lectionary This outline is a devotional reading plan that covers the entire Sacred Scriptures each year. The selections are based on ancient models and are generally in harmony with the liturgical church year. The average reading is three chapters daily. A seasonal can- ticle is assigned for each month and is scheduled to replace the psalm on the first and last days of the month. All of the psalms are read twice a year. The lectionary is in accordance with Martin Luther’s suggestions: “But let the entire Psalter, divided in parts, remain in use and the entire Scriptures, divided into lections, let this be preserved in the ears of the church.” Also: “After that another book should be se- lected, and so on, until the entire Bible has been read through, and where one does not understand it, pass that by and glorify God.” Page 295, Lutheran Worship Concordia Publishing House Those participating in the Daily Lectionary are encouraged to be part of Bethany’s Small Group ministry. An emphasis of these small groups will not only be to discuss the Scripture that we have read, but also to devote ourselves to good works together. Chris- tians sometimes forget that our “devotional lives,” according to Paul, should not only include studying God’s Word (an absolute necessity), but also good works that are just as important. These good works in small groups could be anything that is profitable for others such as: making quilts for Lutheran World Relief, host- ing a meal for Family Promise, volunteering at a charity 5K race, giving rides to health care appointments, or picking up trash in God’s creation. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

PSALMS 60 and 61

PSALMS 60 and 61 Old Testament history confirms the truth that when God has been rejected by his people-- the nation of Israel--he delivers them into the hands of her enemies. In this 60st psalm, Israel is suffering persecution from the Arameans. This psalm commemorates one memorable part of that battle, when Joab returns and kills 12,000 Edomites in the Valley of Salt. David praises God for the triumph, recognizing that the help of man is vain. Psalm 60 For the choir director; according to Shushan Eduth. A Mikhtam of David, to teach; when he struggled with Aram-naharaim and with Aram-zobah, and Joab returned, and smote twelve thousand of Edom in the Valley of Salt. 1 O God, You have rejected us. You have broken us; You have been angry; O, restore us. 2 You have made the land quake, You have split it open; heal its breaches, for it totters. 3 You have made Your people experience hardship; You have given us wine to drink that makes us stagger. 4 You have given a banner to those who fear You, that it may be displayed because of the truth. Selah 5 That Your beloved may be delivered, save with Your right hand, and answer us! 6 God has spoken in His holiness: “I will exult, I will portion out Shechem and measure out the valley of Succoth. 7 “Gilead is Mine, and Manasseh is Mine; Ephraim also is the helmet of My head; Judah is My scepter. 8 “Moab is My washbowl; over Edom I shall throw My shoe; shout loud, O Philistia, because of Me!” 9 Who will bring me into the besieged city? Who will lead me to Edom? 10 Have not You Yourself, O God, rejected us? And will You not go forth with our armies, O God? 11 O give us help against the adversary, for deliverance by man is in vain. -

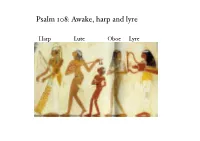

Psalm 108: Awake, Harp and Lyre

Psalm 108: Awake, harp and lyre Harp Lute Oboe Lyre Psalm 108 (107) (Mode 3. 3….12 / 4……271) Psalm 108:1-5 is borrowed from Psalm 57:7-11 and Psalm 108:6-13 is borrowed from Psalm 60:5-12. This gives us an idea how psalms were ‘up-dated’. It also gives us an indication of how careful the writers were in quoting their sources. Psalm 108 seems to belong to the Persian period (5th century BC?) when Judah, along with her neighbours, was part of a Persian province (‘satrapy’). My heart is steadfast, O God, my heart is steadfast. I will sing and make melody. Awake, my soul! Awake, O harp and lyre! I will awake the dawn. Harp Lute Oboe Lyre He stirs himself. It is not God who needs awakening, it is our hearts. ‘Awake, awake, put on strength, O arm of the Lord! … Rouse yourself, rouse yourself! Stand up, O Jerusalem!’(Isaiah 51:9,17). I will give thanks to you, O Lord, among the peoples. I will sing praises to you among the nations. For your kindness is as high as the heavens; your faithfulness extends to the clouds. Rise up, O God, above the heavens. Let your glory fill the earth. ‘By the tender mercy of our God, the dawn from on high will break upon us’(Luke 1:78). ‘Arise, shine; for your light has come, and the glory of the Lord has risen upon you’(Isaiah 60:1). Resurrection through death ‘When you have lifted up the Son of Man, then you will realise that I am he’(John 8:28). -

Psalm Praise: Declarations of Praise from the Psalms

Psalm Praise: Declarations of praise from the Psalms Glory to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit; as it was in the beginning is now and shall be for ever. Amen. □ I will give thanks to the LORD because of his righteousness; Psalm 7:17 and will sing praise to the name of the LORD Most High. □ I will praise you, O LORD, with all my heart; Psalm 9:1-2 I will tell of all your wonders. I will be glad and rejoice in you; I will sing praise to your name, O Most High. □ Sing praises to the LORD, enthroned in Zion; Psalm 9:11 proclaim among the nations what he has done. □ I trust in your unfailing love; Psalm 13:5-6 my heart rejoices in your salvation. I will sing to the LORD, for he has been good to me. □ I will praise the LORD, who counsels me; Psalm 16:7 even at night my heart instructs me. □ The LORD lives! Praise be to my Rock! Psalm 18:46 Exalted be God my Saviour! □ Be exalted O LORD, in your strength; Psalm 21:13 we will sing and praise your might. □ Praise be to the LORD, Psalm 28:6-7 for he has heard my cry for mercy. The LORD is my strength and my shield; my heart trusts in him, and I am helped. My heart leaps for joy, and I will give thanks to him in song. □ Sing to the LORD, you saints of his; Psalm 30:4 praise his holy name. -

“Crying in a Cave”: Psalm 57

Wheelersburg Baptist Church 7/1/07 Brad Brandt Psalm 57 “Crying in a Cave” ** Setting: David was hiding in a cave (1 Sam. 22:1-2; 24:1-3). 1. When you’re in a cave it’s easy to become self-absorbed. 2. When you’re in a cave you have a wonderful opportunity to do what David did. Main Idea: Rather than looking inward and becoming self-absorbed, in Psalm 57 David by God’s help chose to look in four directions. I. David looked up (1-3). A. He asks for mercy from God (1). B. He cries out to God (2-3). II. David looked around (4-6). A. He sees his enemy (4). B. He sees God’s glory (5). C. He sees his enemy’s plot backfire (6). III. David looked ahead (7-10). A. He prepared his heart (7a). B. He resolved to sing (7b). C. He resolved to awaken the coming days with praise (8). D. He resolved to praise the Lord among the nations (9-10). 1. If you really appreciate God you don’t hoard Him. 2. If you really appreciate God, you do all you can to spread His fame. IV. David looked beyond himself (11). A. What really matters in the world is God’s reputation. B. What really matters in the world is God’s plan. Make It Personal: Am I living my life for the glory of God or for some other agenda? When I was growing up on the farm my brother and I and a few others went on a search and find mission. -

Weekly Spiritual Fitness Plan” but the Basic Principles of Arrangement Seem to Be David to Provide Music for the Temple Services

Saturday: Psalms 78-82 (continued) Monday: Psalms 48-53 81:7 “I tested you.” This sounds like a curse. Yet it FAITH FULLY FIT Psalm 48 This psalm speaks about God’s people, is but another of God’s blessings. God often takes the church. God’s people are symbolized by Jerusa- something from us and then waits to see how we My Spiritual Fitness Goals for this week: Weekly Spiritual lem, “the city of our God, his holy mountain . will handle the problem. Will we give up on him? Mount Zion.” Jerusalem refers to the physical city Or will we patiently await his intervention? By do- where God lived among his Old Testament people. ing the latter, we are strengthened in our faith, and But it also refers to the church on earth and to the we witness God’s grace. Fitness Plan heavenly, eternal Jerusalem where God will dwell among his people into eternity. 82:1,6 “He gives judgment among the ‘gods.’” The designation gods is used for rulers who were to Introduction & Background 48:2 “Zaphon”—This is another word for Mount represent God and act in his stead and with his to this week’s readings: Hermon, a mountain on Israel’s northern border. It authority on earth. The theme of this psalm is that was three times as high as Mount Zion. Yet Zion they debased this honorific title by injustice and Introduction to the Book of Psalms - Part 3 was just as majestic because the great King lived corruption. “God presides in the great assembly.” within her. -

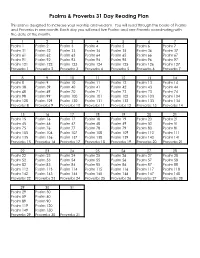

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

PSALMS 90-150 80 Books Four and Five

PSALMS 90-150 80 Books Four and Five BOOK FOUR (Psalms 90-106) Psalm 102: Prayer in time of distress Psalm 90: God and time In this fifth of seven Penitential Psalms, the psalmist experiences emotional and bodily pain and cries out This psalm, amongst other things, reflects on the to God. Because his worldview is that God is the relationship between God and time and the transience cause of all things, he assumes that God is the cause of human life. (See NAB for more.) of his current pain. (See NAB for more.) Psalm 91: God, my shelter Psalm 103: “Thank you, God of Mercy.” Often used for night prayer, this psalm images God This is a psalm of thanksgiving to the God who is full with big wings in whom we can find shelter in times of mercy for sinners. of danger. Much of the psalm hints at the story of the Exodus and wilderness wandering as it speaks of Psalm 104: Hymn of praise to God pathways, dangers, pestilence, tents, and serpents. As the psalmist sojourns along paths laden with dangers, This psalm is a hymn of praise to God the Creator the sole refuge is the Lord who “will cover you with whose power and wisdom are manifested in the his pinions, and under his wings you will find refuge” visible universe. (Ps 91:4). (See NAB for more.) Psalm 105: Another hymn of praise to God Psalm 92: Hymn of thanksgiving to God for his Like the preceding psalm, this didactic historical fidelity hymn praises God for fulfilling his promise to Israel.