Sulphur Springs Stability Study Final Report 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009 Hhtn Djj Directory

Hillsborough Healthy Teen Network 2009-2010 RESOURCE DIRECTORY Questions? Contact Stephanie Johns at [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Organization Page Agenda 4 Alpha House of Tampa Bay, Inc. 5 Bess the Book Bus 5 Bay Area Youth Services – IDDS Program 6 Big Brothers Big Sisters of Tampa Bay 7 Boys and Girls Club of Tampa Bay 7 Center for Autism and Related Disabilities (CARD) 8 Catholic Charities – iWAIT Program 9 The Centre for Women Centre for Girls 9 Family Service Association 10 The Child Abuse Council 11 Family Involvement Connections 11 Breakaway Learning Center 11 Parent as Teachers 12 Children’s Future Hillsborough – FASST Teams 13 Circle C Ranch 14 Citrus Health Care 14 Community Tampa Bay Anytown 15 Hillsborough Youth Collaborative 15 Connected by 25 16 Devereux Florida 17 Falkenburg Academy 17 Family Justice Center of Hillsborough County 18 Sexually Abuse Intervention Network (SAIN) 19 Girls Empowered Mentally for Success (GEMS) 20 Gulfcoast Legal Services 20 Fight Like A Girl (FLAG) 21 For the Family – Motherhood Mentoring Initiative 21 Fresh Start Coalition of Plant City 22 Good Community Alliance 23 He 2 23 Healthy Start Coalition 24 2 Hillsborough County School District Juvenile Justice Transition program 24 Foster Care Guidance Services 25 Hillsborough County Head Start/Early Head Start 25 Expectant Parent Program 27 Hillsborough County Health Department 27 Pediatric Healthcare Program Women’s Health Program 28 House of David Youth Outreach 29 Leslie Peters Halfway House 30 Life Center of the Suncoast 30 Mental Health Care, Inc. 31 Children’s Crisis Stabilization Unit 31 Emotional Behavioral Disabilities Program 31 Empowering Victims of Abuse program 32 End Violence Early Program 32 Family Services Planning Team 33 Home-Based Solutions 34 Life Skills Program 34 Outpatient Program 35 Metro Charities 35 The Ophelia Project and Boys Initiative of Tampa Bay 36 Girls on the Run 36 Ophelia Teen Ambassadors 37 TriBe 37 Project LINK Parent Connect Workshop 38 The Spring of Tampa Bay 39 St. -

![Greenways Trails [EL08] 20110406 Copy.Eps](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8169/greenways-trails-el08-20110406-copy-eps-718169.webp)

Greenways Trails [EL08] 20110406 Copy.Eps

R 17 E R 18 E R 19 E R 20 E R 21 E R 22 E MULTI-USE, PAVED TRAILS Suncoast NAME MILES Air Cargo Road 1.4 G HILLSBOROUGH Al Lopez Park 3.3 BrookerBrooker CreekCreek un n CorridorCorridor Suncoast H Aldermans Ford Park 1.9 w y Trail Amberly Drive 2.8 l B LakeLake DanDan 39 Bayshore Boulevard Greenways 4.4 EquestrianEquestrian TrailTrail Lake s GREENWAYS SYSTEM F z e n Lut rn R P d w OakridgeOakridge Brandon Parkway 1.4 o EquestrianEquestrian TrailTrail HillsboroughHillsborough RRiveriver LLUTZUTZ LAKEAKE FERNF D Bruce B Downs Boulevard 4.8 BrookerBrooker CCreekreek ERN RDRD StateState ParkPark B HeadwatersHeadwaters 75 NNewew TTampaampa Y e Cheney Park 0.3 TrailTrail c A LutzLutz W u Commerce Park Boulevard 1.4 KeystoneKeystone K Tam r BlackwaterBlackwater Bruce B Downs Bl Downs B Bruce R ew pa B A N N Bl FloridaFlorida TrailTrail PPARKWAY L reek CreekCreek PreservePreserve Compton Drive 1.4 C D TrailTrail Bl E E ss Copeland Park 2.3 D K CypressCypress TATAR RRD N SUNSETSUNSET LNLN Cro O R Y P H ON GS T N A I I I O R V CreekCreek SP D G Cross County Greenway 0.8 S 275 G A R H W R H WAYNE RD A YS L R L C T 41 579 C CROOKED LN DairyDairy A O A A Cypress Point Park 1.0 N N L N KeystoneKeystone C P O D E D N LAK R FarmFarm C H D H T r Davis Island Park 0.5 U r O O R U Lake U S D SSUNCOAS 568 D A A Bo N G y S Desotto Park 0.3 co W Keystone T K u P N R I m D L E D BrookerBrooker CreekCreek t Rd 589 l RS EN R V d E VVanan DDykeyke RdRd a GRE DeadDead E Shell Point Road 1.2 Y I NNewew TampaTampa R ConeCone RanchRanch VVanan DDykeyke RRdd AV L LIVINGSTON -

Tampa's New Housing Wave

Tampa’s New Housing Wave Multifamily Fall Report 2015 Rent Growth Accelerates Tourism, Ports Lead Job Gains Investors Devour Properties TAMPA MULTIFAMILY Market Analysis Population Growth Fuels Tampa Multifamily Fall 2015 The Tampa-St. Petersburg’s multifamily market is rebounding nicely, thanks Contacts to strong economic growth and a booming population. The metro’s housing- Paul Fiorilla sensitive economy was among the hardest hit in the nation by the housing- Associate Director of Research driven recession. The metro’s recovery — although uneven — is now moving in [email protected] earnest. As more and more residents ow into the region, the increased demand (800) 866-1124 x5764 stimulates investors’ interest and motivates developers to act quickly. Dana Seeley Employment is growing at above-trend levels, attracting an in ux of residents. Senior Research Analyst Resultant bene ts include a boost in single-family and apartment construction; in- [email protected] creased consumer spending, which bene ts both retailers and the port; and record (800) 866-1124 x2035 tourism, which is driving the leisure and hospitality segment. What’s more, the re- gion is working on a number of infrastructure projects, such as improving toll routes, Jack Kern the completion of a 2.5-mile section of controlled-access highway in Pinellas County Director of Research and Publications and Tampa Electric Co.’s construction of a 25-megawatt solar array in Apollo Beach. [email protected] (800) 866-1124 x2444 Investors are drawn to Tampa’s growth story, with the metro on pace to record $1.8 billion in transactions for the second straight year. -

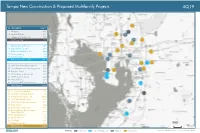

Tampa New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects

Tampa New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 4Q19 ID PROPERTY UNITS 1 Wildgrass 321 3 Union on Fletcher 217 5 Harbour at Westshore, The 192 Total Lease Up 730 15 Bowery Bayside Phase II 589 16 Tapestry Town Center 287 17 Pointe on Westshore, The 444 28 Victory Landing 69 29 Belmont Glen 75 Total Under Construction 1,464 36 Westshore Plaza Redevelopment 500 37 Leisey Road Mixed Used Development 380 38 Progress Village 291 39 Grand Cypress Apartments 324 43 MetWest International 424 44 Waverly Terrace 214 45 University Mall Redevelopment 100 Total Planned 2,233 69 3011 West Gandy Blvd 80 74 Westshore Crossing Phase II 72 76 Village at Crosstown, The 3,000 83 3015 North Rocky Point 180 84 6370 North Nebraska Avenue 114 85 Kirby Street 100 86 Bowels Road Mixed-Use 101 87 Bruce B Downs Blvd & Tampa Palms Blvd West 252 88 Brandon Preserve 200 89 Lemon Avenue 88 90 City Edge 120 117 NoHo Residential 218 Total Prospective 4,525 2 mi Source: Yardi Matrix LEGEND Lease-Up Under Construction Planned Prospective Tampa New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 4Q19 ID PROPERTY UNITS 4 Central on Orange Lake, The 85 6 Main Street Landing 80 13 Sawgrass Creek Phase II 143 Total Lease Up 308 20 Meres Crossing 236 21 Haven at Hunter's Lake, The 241 Total Under Construction 477 54 Bexley North - Parcel 5 Phase 1 208 55 Cypress Town Center 230 56 Enclave at Wesley Chapel 142 57 Trinity Pines Preserve Townhomes 60 58 Spring Center 750 Total Planned 1,390 108 Arbours at Saddle Oaks 264 109 Lexington Oaks Plaza 200 110 Trillium Blvd 160 111 -

06/03/2021 Time: 9:00 Am

6/3/2021 https://atg.tampagov.net/sirepub/cache/2/ocwqayr3wupthgpg3atx41wu/670206032021103059280.htm The Tampa City Council Tampa City Council Chambers City Hall 315 E. Kennedy Blvd, Third Floor Tampa, Florida 33602 REGULAR FINAL AGENDA DATE: 06/03/2021 TIME: 9:00 A.M. Orlando Gudes, Chair District 5 John Dingfelder, Chair Pro-Tem District 3 At-Large Joseph Citro, District 1 At-Large Charlie Miranda, District 2 At-Large Bill Carlson, District 4 Guido Maniscalco, District 6 Luis Viera, District 7 Marn Shelby, City Council Aorney Any person who decides to appeal any decision of the City Council with respect to any maer considered at this meeng will need a record of the proceedings, and for such purpose, may need to hire a court reporter to ensure that a verbam record of the proceedings is made, which record includes the tesmony and evidence upon which the appeal is to be based. In accordance with the Americans with Disabilies Act (“ADA”) and Secon 286.26, Florida Statutes, persons with disabilies needing a reasonable accommodaon to parcipate in this public hearing or meeng should contact the City of Tampa’s ADA Coordinator at least 48 hours prior to the proceeding. The ADA Coordinator may be contacted via phone at 813-274-3964, email at [email protected], or by subming an ADA - Accommodaons Request form available online at tampagov.net/ADARequest. Shirley Foxx-Knowles, CMC City Clerk MEETING CALLED TO ORDER – Orlando Gudes, CHAIR https://atg.tampagov.net/sirepub/cache/2/ocwqayr3wupthgpg3atx41wu/670206032021103059280.htm 1/18 6/3/2021 https://atg.tampagov.net/sirepub/cache/2/ocwqayr3wupthgpg3atx41wu/670206032021103059280.htm Invocaon Pledge of Allegiance Roll Call APPROVAL OF THE AGENDA AND ADDENDUM TO THE AGENDA: CEREMONIAL ACTIVITIES AND\OR PRESENTATIONS: 1. -

Transforming Tampa's Tomorrow

TRANSFORMING TAMPA’S TOMORROW Blueprint for Tampa’s Future Recommended Operating and Capital Budget Part 2 Fiscal Year 2020 October 1, 2019 through September 30, 2020 Recommended Operating and Capital Budget TRANSFORMING TAMPA’S TOMORROW Blueprint for Tampa’s Future Fiscal Year 2020 October 1, 2019 through September 30, 2020 Jane Castor, Mayor Sonya C. Little, Chief Financial Officer Michael D. Perry, Budget Officer ii Table of Contents Part 2 - FY2020 Recommended Operating and Capital Budget FY2020 – FY2024 Capital Improvement Overview . 1 FY2020–FY2024 Capital Improvement Overview . 2 Council District 4 Map . 14 Council District 5 Map . 17 Council District 6 Map . 20 Council District 7 Map . 23 Capital Improvement Program Summaries . 25 Capital Improvement Projects Funded Projects Summary . 26 Capital Improvement Projects Funding Source Summary . 31 Community Investment Tax FY2020-FY2024 . 32 Operational Impacts of Capital Improvement Projects . 33 Capital Improvements Section (CIS) Schedule . 38 Capital Project Detail . 47 Convention Center . 47 Facility Management . 49 Fire Rescue . 70 Golf Courses . 74 Non-Departmental . 78 Parking . 81 Parks and Recreation . 95 Solid Waste . 122 Technology & Innovation . 132 Tampa Police Department . 138 Transportation . 140 Stormwater . 216 Wastewater . 280 Water . 354 Debt . 409 Overview . 410 Summary of City-issued Debt . 410 Primary Types of Debt . 410 Bond Covenants . 411 Continuing Disclosure . 411 Total Principal Debt Composition of City Issued Debt . 412 Principal Outstanding Debt (Governmental & Enterprise) . 413 Rating Agency Analysis . 414 Principal Debt Composition . 416 Governmental Bonds . 416 Governmental Loans . 418 Enterprise Bonds . 419 Enterprise State Revolving Loans . 420 FY2020 Debt Service Schedule . 421 Governmental Debt Service . 421 Enterprise Debt Service . 422 Index . -

Regional Superintendents

Hillsborough County Public Schools Region Superintendent School Assignments Elementary Region 1 Elementary Region 2 Elementary Region 3 Elementary Region 4 Elementary Region 5 School/Center Site School/Center Site School/Center Site School/Center Site School/Center Site Anderson 0121 Alexander 0081 Carrollwood 0701 Alafia 0271 Apollo Beach 0141 Ballast Point 0161 Bay Crest 0191 Chiles 0772 Bailey 0092 Belmont 0009 Chiaramonte 0771 Bellamy 1776 Clark 0851 Bing 0261 Bevis 0361 Dickenson 1101 Bryant 0527 Claywell 0861 Buckhorn 0571 Boyette Springs 0311 Gorrie 1681 Cannella 0691 Essrig 1431 Cimino 0802 Brooker 0401 Grady 1721 Citrus Park 0801 Heritage 1831 Colson 0931 Collins 0065 Just 0282 Crestwood 1021 Hunter's Green 1941 Cork 1001 Corr 0054 Lamb 0128 Davis 0056 Lake Magdalene 2321 Frost 0070 Cypress Creek 1051 Lanier 2361 Deer Park 0100 Lewis 2451 Ippolito 1951 Dawson 0005 Lomax Magnet 2521 Egypt Lake 1401 Limona 2431 Knights 2291 Doby 0072 Mabry 2601 Hammond 0102 Lutz K-8 2561 Lincoln Magnet 2441 FishHawk Creek 0059 MacFarlane Park 0060 Lowry 2551 Maniscalco K-8 2771 Lopez 2531 Kingswood 2261 Mendenhall 2961 McKitrick 3082 Muller Magnet 3181 Nelson 3141 Lithia Springs 2461 Mitchell 3081 Morgan Woods 3101 Oak Grove 3161 Pinecrest 3362 Mintz 3061 Rampello K-8 4251 Northwest 3151 Pride 3441 Robinson Elem. 3681 Riverview Elem. 3641 Roland Park K-8 3802 Schwarzkopf 3861 Riverhills 3622 Springhead 4161 Ruskin 3841 Roosevelt 3801 Seminole Heights 3921 Schmidt 3851 Trapnell 4481 Sessums 3922 Shore Magnet 3961 Sullivan Part. 0123 Seffner 3881 Valrico 4581 Stowers 0085 Tampa Bay Blvd 4241 Town & Country 4441 Tampa Palms 4261 Walden Lake 4591 Summerfield 4211 Tinker K-8 4381 Twin Lakes 4561 Turner/Bartels K-8 0069 Wilson Elem. -

Tampa Early Lighting and Transportation Arsenio M

Sunland Tribune Volume 17 Article 7 2018 Tampa Early Lighting and Transportation Arsenio M. Sanchez Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune Recommended Citation Sanchez, Arsenio M. (2018) "Tampa Early Lighting and Transportation," Sunland Tribune: Vol. 17 , Article 7. Available at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune/vol17/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sunland Tribune by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAMPA EARLY LIGHTING AND TRANSPORTATION By ARSENIO M. SANCHEZ An early Tampa Electric Company (not the After signing the contract the electric present Co.) was organized on January 29, company became expansion-minded. More 1887. powerful generators were needed; and to obtain money to buy them, the company was About three months later the company reorganized, becoming Tampa Light & brought the first Electric lights to the city of Power Company, with Solon B. Turman as Tampa. A small Westinghouse generator President. was brought in and two arc lights were erected, one at the corner of Franklin and Tampa had to wait for its lights, however. Washington Streets; and one in front of the An epidemic of yellow fever struck the city, brand new "Dry Goods Palace." bringing progress to a halt; and the new electric light system was not installed until Tampa's first "light show" took place May of 1888. A power plant was built at the Monday, April 28, 1887. Word got around corner of Tampa and Cass Streets. -

Unlocking Tampa Bay – Treasure Awaits

Media Contact: Kelly Prieto, APR Hayworth Public Relations (813) 318-9611 [email protected] Culinary Related media inquiries: Brooke Palmer Bern’s Steak House (727) 235-2389 Year 2017 [email protected] Unlocking Tampa Bay – Treasure Awaits TAMPA – The Epicurean Hotel rises from the heart of the vibrant city of Tampa, Fla., bringing a new level of contemporary comfort and style to the Hyde Park historic district. From the thrill of major league sports to the authentic charm of Tampa’s unique history, the Epicurean is the gateway to exploring one of Florida’s most beloved destinations. With distinctive vibes and cultures emanating from each of the city’s districts, Tampa always surprises visitors with something new to explore and experience. While staying at the Epicurean, guests can expect anything but a generic hotel experience. The hotel’s well-connected Epicurean Hosts give adventurous guests an inside track for finding the area’s genuine and enriching local experiences. From “locals-only” restaurants and hidden shopping gems, to the best bike routes and museum exhibitions, a chat with the Epicurean Hosts will leave guests feeling as if they own the city. Guests don’t have to travel far from the hotel to experience more of Tampa’s premier dining, nightlife and shopping. Directly across the street, the legendary Bern’s Steak House is a destination all its own, where diners can tour the kitchen and wine cellar and pay a visit to the famous Harry Waugh Dessert Room. Bern’s sister restaurant, Haven, thrills foodies with whimsical small plates, housemade charcuterie, cultured artisanal cheeses, crafted cocktails and cellared wine selections. -

Title I Public Schools 2020-2021

TITLE I PUBLIC SCHOOLS 2020-2021 ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS (91) MIDDLE SCHOOLS (26) EXCEPTIONAL/ALT CENTERS (10) Alexander McDonald T3* Adams* Brandon EPIC 3 Center Bailey Mendenhall Buchanan Caminiti Exceptional Bay Crest Miles T2* Burnett Carver Exceptional Bellamy Mintz Dowdell Dorothy Thomas Bing T1 Morgan Woods Eisenhower Lavoy Exceptional Broward T1* Mort T2* Ferrell Lopez Exceptional Bryan T2 Muller Franklin Mendez Exceptional Burney T1* Oak Grove Giunta* North Tampa EPIC 3 Center Cannella Oak Park T3* Greco T2 Simmons Exceptional Chiaramonte Palm River T3 Jennings T1* Willis Peters Clair Mel T2 Pinecrest Madison CHARTER SCHOOLS (17) Cleveland T2* Pizzo K-6 T2* Mann Advantage Academy K-8 Colson Potter T3* Marshall BridgePrep Academy of Riverview K-8 Cork Reddick T2 McLane T2 BridgePrep Academy of Tampa K-8 Corr Riverview Elem Memorial T2 East Tampa K-2 Crestwood Robinson Monroe Excelsior Prep Charter School K-5 Cypress Creek Robles T3* Orange Grove Florida Autism Charter School PK-12 Davis Ruskin T1 Pierce Henderson Hammock K-8 Desoto* Schmidt Sgt. Smith Legacy Preparatory Academy K-8 Dickenson Seffner Shields T2 New Springs School K-8 Dover T3 Seminole Sligh T2 RCMA Wimauma Academy K-8 Dunbar T1* Shaw T3* Stewart Seminole Heights Charter School 9-12 Edison T2 Sheehy T3 Tomlin The Collaboratory Preparatory Academy K-8 Egypt Lake Shore Turkey Creek Village of Excellence Elem K-5 Folsom T3* Springhead Webb Village of Excellence Middle School 6-8 Forest Hills T3 Sullivan T2 Young Walton Academy for the Performing Arts K-5 Foster T3* Sulphur -

Tampa Heights Historic District

'-~=------. i;f/~-: NPS Form 10-900 (Oct. 1990) ~-ECEIVE(?"IJ~''::'1 '• l UnlJedUnijted State,States D~rtmttntDea)artinent .of thethe.. lnJe(lorInferior . -, / ! National Park Seiylcfl , , National Park Secyicd , JJ. National Register of Historic Places _____6- __. ~ . National Register of Historic Places Registration Form INTERAGENCY RESOURCE;. :f This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individualindividuai properties and tthliiiili■· ’ISSSE*' faaJnattuctionsNA~IONA~,fs~~~~te m"ftd>ftrBv66»tefe t~the I; National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by mariiidikliiy ing X lli<th»«pp(aB(iatgJox· x or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property bebeinging documented, enter "NIA"“N/A” for "not“not applicable."applicable.” For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter,typewriter, word processorprocessor,, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property .. , historic name __Tanpa='-'-"--C..C........CHei.~'-·Tampa Heightsgh.,__ts-'---_Hi_._s_to_r_i_c_D_i_s_tr_i_c_t Historic District____ _ ______________ other names/site number .__-'N'"'--A N/A____________________________ _ 2. Location Bounded by Adal6eAdalee St., I-275,1-275, 7th Ave. street & number and N. TairpaTampa Ave._____________________ N/lt:J not for -

Chicago Downtown Chicago Connections

Stone Scott Regional Transportation 1 2 3 4 5Sheridan 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Dr 270 ter ss C en 619 421 Edens Plaza 213 Division Division ne 272 Lake Authority i ood s 422 Sk 422 u D 423 LaSalle B w 423 Clark/Division e Forest y okie Rd Central 151 a WILMETTE ville s amie 422 The Regional Transportation Authority r P GLENVIEW 800W 600W 200W nonstop between Michigan/Delaware 620 421 0 E/W eehan Preserve Wilmette C Union Pacific/North Line 3rd 143 l Forest Baha’i Temple F e La Elm ollw Green Bay a D vice 4th v Green Glenview Glenview to Waukegan, Kenosha and Stockton/Arlington (2500N) T i lo 210 626 Evanston Elm n (RTA) provides financial oversight, Preserve bard Linden nonstop between Michigan/Delaware e Dewes b 421 146 s Wilmette 221 Dear Milw Foster and Lake Shore/Belmont (3200N) funding, and regional transit planning R Glenview Rd 94 Hi 422 221 i i-State 270 Cedar nonstop between Delaware/Michigan Rand v r Emerson Chicago Downtown Central auk T 70 e Oakton National- Ryan Field & Welsh-Ryan Arena Map Legend Hill 147 r Cook Co 213 and Marine/Foster (5200N) for the three public transit operations Comm ee Louis Univ okie Central Courts k Central 213 93 Maple College 201 Sheridan nonstop between Delaware/Michigan Holy 422 S 148 Old Orchard Gross 206 C Northwestern Univ Hobbie and Marine/Irving Park (4000N) Dee Family yman 270 Point Central St/ CTA Trains Hooker Wendell 22 70 36 Bellevue L in Northeastern Illinois: The Chicago olf Cr Chicago A Harrison 54A 201 Evanston 206 A 8 A W Sheridan Medical 272 egan osby Maple th Central Ser 423 201 k Illinois Center 412 GOLF Westfield Noyes Blue Line Haines Transit Authority (CTA), Metra and Antioch Golf Glen Holocaust 37 208 au 234 D Golf Old Orchard Benson Between O’Hare Airport, Downtown Newberry Oak W Museum Nor to Golf Golf Golf Simpson EVANSTON Oak Research Sherman & Forest Park Oak Pace Suburban bus.