Plastic and Other Microfibers in Sediments, Macroinvertebrates And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Tew and Pirate Settlements of the Indo - Atlantic Trade World, 1645 -1730 1 Kevin Mcdonald Department of History University of California, Santa Cruz

‘A Man of Courage and Activity’: Thomas Tew and Pirate Settlements of the Indo - Atlantic Trade World, 1645 -1730 1 Kevin McDonald Department of History University of California, Santa Cruz “The sea is everything it is said to be: it provides unity, transport , the means of exchange and intercourse, if man is prepared to make an effort and pay a price.” – Fernand Braudel In the summer of 1694, Thomas Tew, an infamous Anglo -American pirate, was observed riding comfortably in the open coach of New York’s only six -horse carriage with Benjamin Fletcher, the colonel -governor of the colony. 2 Throughout the far -flung English empire, especially during the seventeenth century, associations between colonial administrators and pirates were de rig ueur, and in this regard , New York was similar to many of her sister colonies. In the developing Atlantic world, pirates were often commissioned as privateers and functioned both as a first line of defense against seaborne attack from imperial foes and as essential economic contributors in the oft -depressed colonies. In the latter half of the seventeenth century, moreover, colonial pirates and privateers became important transcultural brokers in the Indian Ocean region, spanning the globe to form an Indo-Atlantic trade network be tween North America and Madagascar. More than mere “pirates,” as they have traditionally been designated, these were early modern transcultural frontiersmen: in the process of shifting their theater of operations from the Caribbean to the rich trading grounds of the Indian Ocean world, 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the “Counter -Currents and Mainstreams in World History” conference at UCLA on December 6-7, 2003, organized by Richard von Glahn for the World History Workshop, a University of California Multi -Campus Research Unit. -

The 20 February 2010 Madeira Flash-Floods

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 12, 715–730, 2012 www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci.net/12/715/2012/ Natural Hazards doi:10.5194/nhess-12-715-2012 and Earth © Author(s) 2012. CC Attribution 3.0 License. System Sciences The 20 February 2010 Madeira flash-floods: synoptic analysis and extreme rainfall assessment M. Fragoso1, R. M. Trigo2, J. G. Pinto3, S. Lopes1,4, A. Lopes1, S. Ulbrich3, and C. Magro4 1IGOT, University of Lisbon, Portugal 2IDL, Faculty of Sciences, University of Lisbon, Portugal 3Institute for Geophysics and Meteorology, University of Cologne, Germany 4Laboratorio´ Regional de Engenharia Civil, R.A. Madeira, Portugal Correspondence to: M. Fragoso ([email protected]) Received: 9 May 2011 – Revised: 26 September 2011 – Accepted: 31 January 2012 – Published: 23 March 2012 Abstract. This study aims to characterise the rainfall ex- island of Madeira is quite densely populated, particularly in ceptionality and the meteorological context of the 20 Febru- its southern coast, with circa 267 000 inhabitants in 2011 ary 2010 flash-floods in Madeira (Portugal). Daily and census, with 150 000 (approximately 40 %) living in the Fun- hourly precipitation records from the available rain-gauge chal district, one of the earliest tourism hot spots in Europe, station networks are evaluated in order to reconstitute the currently with approximately 30 000 hotel beds. In 2009, the temporal evolution of the rainstorm, as its geographic inci- archipelago received 1 million guests; this corresponds to an dence, contributing to understand the flash-flood dynamics income of more than 255 Million Euro (INE-Instituto Na- and the type and spatial distribution of the associated im- cional de Estat´ıstica, http://www.ine.pt). -

Analysis of Y-Chromosome and Mtdna Variability in the Madeira Archipelago Population

International Congress Series 1288 (2006) 94–96 www.ics-elsevier.com Analysis of Y-chromosome and mtDNA variability in the Madeira Archipelago population Ana T. Fernandes *, Rita Gonc¸alves, Alexandra Rosa, Anto´nio Brehm Human Genetics Laboratory, University of Madeira, Campus of Penteada, Funchal, Portugal Abstract. The Atlantic archipelago of Madeira is made up of two islands (Madeira and Porto Santo) with 250,000 inhabitants. These islands were discovered and settled by the Portuguese in the 15th century and played an important role in the complex Atlantic trade network in the following centuries. The genetic composition of the Madeira Islands’ population was investigated by analyzing Y-chromosomal bi-allelic and STR markers in three different regions of the main island plus Porto Santo. We compared the results with mtDNA data and used the Y-chromosome STRs to determine the variability within each haplogroup. A sample of 142 unrelated males divided into four groups (Funchal City, West Madeira, North and East Madeira and Porto Santo) were analyzed. Significant genetic differences between these regions and the population of Funchal were found. The population of Funchal had lower gene diversity than expected. D 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Madeira Island; Y-chromosome; mtDNA 1. Introduction The Madeira archipelago is made up of two inhabited islands, Madeira and Porto Santo, and has a population of about 250,000 inhabitants, with more than half living in Funchal. The Portuguese colonized the Madeira Archipelago in the 15th century and, in the beginning of the colonization, the archipelago was divided into three parts (Southwest and Northeast in the Madeira Island, and Porto Santo) and given to three administrators [1]. -

Chapter I the Portuguese Empire

Decay or defeat ? : an inquiry into the Portuguese decline in Asia 1580-1645 Veen, Ernst van Citation Veen, E. van. (2000, December 6). Decay or defeat ? : an inquiry into the Portuguese decline in Asia 1580-1645. Research School of Asian, African, and Amerindian Studies (CNWS), Leiden University. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/15783 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/15783 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). CHAPTER I THE PORTUGUESE EMPIRE The boundaries Until well into the seventeenth century, as far as the Iberians were concerned, the way the world was divided and the role they were to play therein as champions of the church was clear-cut and straightforward. Already in the fifteenth century the rights of the Portuguese monarchs on the portus, insulas, terras et maria still to be conquered had been confirmed by Papal edicts. They bestowed the privilege to intrude into the countries of the Saracenes and heathens, to take them prisoner, take all their possessions and reduce them to eternal slavery. Derived from this right of conquest were the rights of legislation, jurisdiction and tribute and the monopolies of navigation, trade and fishing. Besides, the kings were allowed to build churches, cloisters and other holy places and to send clergy and other volunteers, to spread the true religion, to receive confessions and to give absolutions. Excommunication or interdiction were the penalties for Christians who violated these royal monopolies.1 As the Castilians were just as keen on the collection of slaves and gold and the overseas expansion of the mission, a clash of interests was inevitable.2 In 1479, the Castilians used the opportunity of king Afonso V's defeat, after he attempted to acquire the Castilian throne, to establish their rights on the Canary islands. -

Madeira and the Beginnings of New World Sugar Cane Cultivation and Plantation Slavery: a Study in Institution Building*

MADEIRA AND THE BEGINNINGS OF NEW WORLD SUGAR CANE CULTIVATION AND PLANTATION SLAVERY: A STUDY IN INSTITUTION BUILDING* Sidney M. Greenfield Department of Anthropology The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53201 Although the tropical New World is generally taken as the context for the comparative and historical study of plantation systems and of slavery, the institutional complex of the slave plantation' did not have its origins in the Western Hemisphere. Instead, as Charles Verlinden2 and others have demon- strated so ably, the culture complex can be traced back to the European colonies established in Palestine following the First Crusade. There sugar was grown by a mixed force of free and slave workers. The sugar then was exported, with some of it reaching the developing markets of Western Europe. Sugar cane had been known to Europe at least as far back as antiquity, although its distribution was limited. The cultivation of the crop, and its in- creased availability and wider distribution, came to Mediterranean Europe in the wake of the expansion of Islam. Sugar cane, most probably first domesticated in India, had been grown in Asia Minor and was carried along with the spread of Islam to the coastal regions of North Africa, the islands of the Mediterranean, and eventually to the Moorish kingdoms in the Iberian peninsula.3 Given the intensity of the conflict between Christianity and Islam during the Middle Ages, trade between the areas controlled by the rival religions tended to be minimal. Hence sugars produced in areas under Moslem control went, for the most part, to supply markets in the Near East and North Africa, while the markets of Europe had to be supplied from areas under Christian control. -

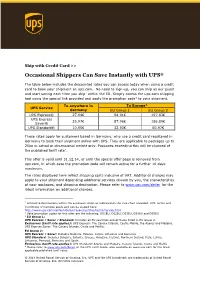

Occasional Shippers Can Save Instantly with UPS®

Ship with Credit Card >> Occasional Shippers Can Save Instantly with UPS® The table below includes the discounted rates you can access today when using a credit card to book your shipment on ups.com. No need to sign-up, you can ship as our guest and start saving each time you ship1 within the EU. Simply access the ups.com shipping tool using the special link provided and apply the promotion code2 to your shipment. To anywhere in To Europe3 UPS Service Germany EU Group 1 EU Group 2 UPS Express® 27.94€ 94.01€ 197.83€ UPS Express 25.97€ 87.96€ 186.89€ Saver® UPS Standard® 10.95€ 32.93€ 50.97€ These rates apply for customers based in Germany, who use a credit card registered in Germany to book their shipment online with UPS. They are applicable to packages up to 20kg in actual or dimensional weight only. Packages exceeding this will be charged at the published tariff rate4. This offer is valid until 31.12.14, or until the special offer page is removed from ups.com, in which case the promotion code will remain active for a further 10 days maximum. The rates displayed here reflect shipping costs inclusive of VAT. Additional charges may apply to your shipment depending additional services chosen by you, the characteristics of your packages, and shipping destination. Please refer to www.ups.com/de/en for the latest information on additional charges. 1 Limited to destinations within the European Union as indicated on the rate chart provided. UPS Terms and Conditions of Carriage apply and can be viewed here: http://www.ups.com/content/de/en/resources/ship/terms/service.html 2 Valid promotion codes for this offer are the following: DE1EU, DE2EU, DE3EU, DE4EU and DE5EU 3 EU Group 1: UPS Express / Saver / Standard: Includes all EU countries except those listed in EU Group 2. -

Socotra Archipelago – a Lifeboat in the Sea of Changes: Advancement in Socotran Insect Biodiversity Survey

ACTA ENTOMOLOGICA MUSEI NATIONALIS PRAGAE Published 17.xii.2012 Volume 52 (supplementum 2), pp. 1–26 ISSN 0374-1036 Socotra Archipelago – a lifeboat in the sea of changes: advancement in Socotran insect biodiversity survey Jan BATELKA Nad Vodovodem 16, CZ-100 00 Prague 10, Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Nature conditions in the Socotra Archipelago are briefl y summarised, main factors contributing to the composition and diversity of the insect fauna, i.e. geological history, geographic position, geomorphology, climatic conditions and plant diversity, are circumscribed. Results of the Socotran invertebrate biodiversity research are reviewed, the fi rst annotated list of 40 insect genera and subgenera endemic to the Socotra Archipelago is provided. Recorded high level of ende- mism in the Socotra Island is in accordance with the estimated geological age and continuous stability of its ecosystem. Brief comparison of biodiversity in Socotra and Seychelles Islands – both granitic archipelagos of Gondwanan origin in the West Indian Ocean – is performed. Difference in composition of insect fauna in Socotra and allied Abd el Kuri Island is commented. Main threats and conservation issues concerning the fragile Socotran ecosystem are summarised, and examples of possible consequences for insect fauna are given. Based on comparison of scarce outputs and research activities concerning the Socotran insect fauna so far with the number of those elaborated for other countries/islands, establishing of a long-term insect survey is recommended. Key words. Review, insularity, geology, fl ora, climate, biodiversity, endemism, insect genera, habitat conservation, insect survey, Yemen, Socotra Introduction Because of their remarkable richness in endemic forms, study of the isolated biotas (also called ‘insularity’) has been one of the most interesting topics among naturalists and especially evolutionary biologists since the second half of the 19th century (WITT & MALIAKAL-WITT 2007). -

In Our Heritage If the Scholars Were Killed

Aloe vera, Plant Symbolism and the Threshing Floor Item Type Article Authors Crosswhite, Frank S.; Crosswhite, Carol D. Publisher University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Journal Desert Plants Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 25/09/2021 15:59:47 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/552247 Crosswhite and Crosswhite Aloe and the Threshing Floor 43 Introduction Aloevera,Plant Aloe vera figured prominently in the medicine of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. We think that the early medical practitioners Symbolism and the were very skillful and knowledgeable but understandably tight- lipped concerning the sources of their cures, which were also the sources of their livelihood. In these early civilizations, proprietary Threshing Floor: societies were formed around the cultivation and use of certain plants. There was an extremely precarious period before the Light, Life and Good invention of writing when specific knowledge was vested only in the minds of a few scholars in specific societies. When warriors from one city sacked another city, important knowledge was lost in Our Heritage if the scholars were killed. In other instances knowledge was diffused at the point of the sword! In order to preserve secrets, key plants used by a society could be grown in a clandestine location. It would have been difficult, With Special Reference to the but certainly not impossible, to have hidden the huge fields of Akkadians, Akhenaton, Moses, Aloe which must have been required by the practitioners. We suspect that the populations of Aloe on warm islands such as Alexander the Great, Dioscorides Socotra, and later the Canary Islands, Madeira, and the Cape Verdes might have been introduced by man. -

Age Structure and Growth of Dracaena Cinnabari Populations on Socotra

Trees (2004) 18:43–53 DOI 10.1007/s00468-003-0279-6 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Radim Adolt · Jindrich Pavlis Age structure and growth of Dracaena cinnabari populations on Socotra Received: 10 January 2003 / Accepted: 28 May 2003 / Published online: 26 July 2003 Springer-Verlag 2003 Abstract Unique Dracaena cinnabari woodlands on blood resin is available (Himmelreich et al. 1995; Socotra Island—relics of the Mio-Pliocene xerophile- Vachalkova et al. 1995), too few studies on growth sclerophyllous southern Tethys Flora—were examined in dynamic, phenology and ageing of arborescent Dracaena detail, especially with regard to their age structure. sp. have been implemented. Detailed statistical analyses of sets of 50 trees at four The age of fabulous dragon trees is thus still generally localities were performed in order to define a model clouded in overestimation by Humboldt (1814) who reflecting relationships between specific growth habit and hypothesized that a huge Dracaena draco with 15 m stem actual age. The problematic nature of determining the age girth from Orotava, Tenerife was several thousand years of an individual tree or specific populations of D. old. A more probable average figure of up to 700 years cinnabari is illustrated by three models relating to orders old was suggested by Bystrm (1960). However, later of branching, frequency of fruiting, etc. which allow the observations by Symon (1974) and Magdefrau (1975) actual tree age to be calculated. Based on statistical brought both a precise record of the age of cultivated trees analyses as well as direct field observations, D. cinnabari and also the first clues on determination of ageing. -

Persistence of the Plantation and National Agricultural Problems

Persistence of the Plantation and National Agricultural Problems MERLE C. PRUNTY Department of Geography University of Georgia There are two objectives that I hope to satisfy in this discussion. The first is to establish the persistence, the viability and. flexibility under a wide variety of conditions, of the plantation as an agricultural operational type from medieval times in the Medi terranean to the present on the American scene. The second objective is to assess some of the problems confronting the management of properties of the plantation type in regard to our national agricultural problems, and the potentials therein for changing the directions of policymaking. It is necessary to define the term "plantation", and the operational system which it compasses, at the outset. Plantations have been variously defined by scholars in different fields. My definition, that of a geographer, is broad enough to encompass the interests of most specialists in other disciplines and it has withstood examination by scholars here and abroad for more than two decades. I have defined the plantation as comprising the following five elements (Prunty, 1955): 1. a large landholding, large enough to be distinguishable from the "family farm"; 2. a distinct division of labor and management functions, with management customarily in the hands of the owner. Generally it has taken the equivalent of at least five full-time employees to permit management to emerge as a full-time function embodied in one individual; 89 MERLE C" PRUNTY 3. specialized agricultural production, usually involving two or three specialties per proprietorship, and most of the production destined for cash sale; 4. -

CLASSIC RAYON 100% Viscose

CLASSIC RAYON 100% viscose While every attempt is made to reproduce thread colors accurately, colors on your monitor or print out may not precisely match thread colors. Color names are for your reference only. When ordering please refer to each color by color number. 1013 Peach Blush 1111 Evening Mist 1015 Desert Bloom 1031 Frosted Lavender 1317 Blush Pink 1235 Crocus 1220 Conch Shell 1320 Purple Heart 1307 Raspberry Punch 1388 Plum 1485 Electric Red 1319 Iris 1039 Brick Red 1488 Dark Magenta 1038 Barn Red 1310 Magenta 1114 Pink Petal 1321 Bubble Gum Pink 1115 Powder Puff 1121 Candy Heart 1315 Pink Grapefruit 1309 Dahlia 1148 Rustic Pink 1109 Pink Rose 1384 Merlot 1110 Fuchsia 1385 Garnet 1383 Pink Pansy 1182 Mulberry 1187 Orchid 1281 Radish 1234 Hibiscus 1184 Scarlet Rose 1117 Flamingo Pink 1154 Lipstick Rose 1183 Cranberry 1107 Honeysuckle 1389 Bordeaux 1014 Bermuda Sand 1034 Vintage Rose 1120 Baby Pink 1119 English Rose 1116 Cotton Candy 1035 Burgundy 1108 Pink Carnation 1386 Eggplant 1354 Watermelon 1356 Pink Pearl 1081 Azalea 1141 Mauve 1186 Ruby Slipper 1382 Colonial Rose 1381 Ripe Raspberry 1236 Plum Brandy 3 4 CLASSIC RAYON 100% viscose While every attempt is made to reproduce thread colors accurately, colors on your monitor or print out may not precisely match thread colors. Color names are for your reference only. When ordering please refer to each color by color number. 1261 Lavendula 1198 Moonstone 1266 Regal Blue 1030 Light Periwinkle 1166 Hanukkah Blue 1364 Storm Sky Blue 1466 Sailor Blue 1365 Dusty Plum 1335 Dark Periwinkle -

The Age of Exploration

HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY Native American The Age of Exploration Teacher Guide Enslaved workers Spice trade John Cabot Crossing the ocean The Age of Exploration Teacher Guide Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free: to Share—to copy, distribute, and transmit the work to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution—You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation (www.coreknowledge.org) made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial—You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Copyright © 2016 Core Knowledge Foundation www.coreknowledge.org All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge®, Core Knowledge Curriculum Series™, Core Knowledge History and Geography™ and CKHG™ are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. References herein should not be regarded as affecting the validity of said trademarks and trade names.