Summary Report of the Situation Analysis of Widows in Religious Places of West Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paper Code: Dttm C205 Tourism in West Bengal Semester

HAND OUT FOR UGC NSQF SPONSORED ONE YEAR DILPOMA IN TRAVEL & TORUISM MANAGEMENT PAPER CODE: DTTM C205 TOURISM IN WEST BENGAL SEMESTER: SECOND PREPARED BY MD ABU BARKAT ALI UNIT-I: 1.TOURISM IN WEST BENGAL: AN OVERVIEW Evolution of Tourism Department The Department of Tourism was set up in 1959. The attention to the development of tourist facilities was given from the 3 Plan Period onwards, Early in 1950 the executive part of tourism organization came into being with the appointment of a Tourist Development Officer. He was assisted by some of the existing staff of Home (Transport) Department. In 1960-61 the Assistant Secretary of the Home (Transport) Department was made Director of Tourism ex-officio and a few posts of assistants were created. Subsequently, the Secretary of Home (Transport) Department became the ex-officio Director of Tourism. Two Regional Tourist Offices - one for the five North Bengal districts i.e., Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, Cooch Behar, West Dinajpur and Maida with headquarters at Darjeeling and the other for the remaining districts of the State with headquarters at Kolkata were also set up. The Regional Office at KolKata started functioning on 2nd September, 1961. The Regional Office in Darjeeling was started on 1st May, 1962 by taking over the existing Tourist Bureau of the Govt. of India at Darjeeling. The tourism wing of the Home (Transport) Department was transferred to the Development Department on 1st September, 1962. Development. Commissioner then became the ex-officio Director of Tourism. Subsequently, in view of the increasing activities of tourism organization it was transformed into a full-fledged Tourism Department, though the Secretary of the Forest Department functioned as the Secretary, Tourism Department. -

The Gazette of India

REGD. NO. D. L.-33004/99 The Gazette of India EXTRAORDINARY PART II—Section 3—Sub-section (i) PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 183] NEW DELHI, THURSDAY, APRIL 15, 1999/CHAITRA 25, 1921 1136 GI/99-1A (i) 2 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC. 3(i)] 3 4 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC. 3(i)] 5 6 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC. 3(i)] 7 8 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA : EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC 3 (i)] 9 10 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA : EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC. 3 (i)] 11 12 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA : EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC. 3 (i)] 13 14 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY PART II—SEC. 3(i)] 15 16 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC 3(i)] 17 18 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA : EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC. 3(i)] 19 20 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC, 3(i)] 21 22 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC. 3(i)] 23 24 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC. 3(i)] 25 26 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC. 3(i)] 27 28 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC. 3(i)] 29 30 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA; EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC. 3(i)] 31 32 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA : EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC. 3 (i)] 33 34 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA • EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC 3(i)] 1136 GI/99 311 35 36 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY |PART II—SEC. 3(i)] 37 38 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC. -

Colonial Transformation and Asian Religions in Modern History

Colonial Transformation and Asian Religions in Modern History Colonial Transformation and Asian Religions in Modern History Edited by David W. Kim Colonial Transformation and Asian Religions in Modern History Edited by David W. Kim This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by David W. Kim and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0559-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0559-9 CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures ......................................................................... vii Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Preface ........................................................................................................ xi Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Part One: South Asia Chapter One ............................................................................................... 10 From Colony to Post-Colony: Animal Baiting and Religious Festivals in South Punjab, Pakistan Muhammad Amjad Kavesh Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

Rainfall, North 24-Parganas

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2016 - 17 NORTHNORTH 2424 PARGANASPARGANAS,, BARASATBARASAT MAP OF NORTH 24 PARGANAS DISTRICT DISASTER VULNERABILITY MAPS PUBLISHED BY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA SHOWING VULNERABILITY OF NORTH 24 PGS. DISTRICT TO NATURAL DISASTERS CONTENTS Sl. No. Subject Page No. 1. Foreword 2. Introduction & Objectives 3. District Profile 4. Disaster History of the District 5. Disaster vulnerability of the District 6. Why Disaster Management Plan 7. Control Room 8. Early Warnings 9. Rainfall 10. Communication Plan 11. Communication Plan at G.P. Level 12. Awareness 13. Mock Drill 14. Relief Godown 15. Flood Shelter 16. List of Flood Shelter 17. Cyclone Shelter (MPCS) 18. List of Helipad 19. List of Divers 20. List of Ambulance 21. List of Mechanized Boat 22. List of Saw Mill 23. Disaster Event-2015 24. Disaster Management Plan-Health Dept. 25. Disaster Management Plan-Food & Supply 26. Disaster Management Plan-ARD 27. Disaster Management Plan-Agriculture 28. Disaster Management Plan-Horticulture 29. Disaster Management Plan-PHE 30. Disaster Management Plan-Fisheries 31. Disaster Management Plan-Forest 32. Disaster Management Plan-W.B.S.E.D.C.L 33. Disaster Management Plan-Bidyadhari Drainage 34. Disaster Management Plan-Basirhat Irrigation FOREWORD The district, North 24-parganas, has been divided geographically into three parts, e.g. (a) vast reverine belt in the Southern part of Basirhat Sub-Divn. (Sundarban area), (b) the industrial belt of Barrackpore Sub-Division and (c) vast cultivating plain land in the Bongaon Sub-division and adjoining part of Barrackpore, Barasat & Northern part of Basirhat Sub-Divisions The drainage capabilities of the canals, rivers etc. -

+91-99117-75120 TRAVEL PLAN Detailed Itinerary

Website: www.alifetimetrip.co.in Email: [email protected] Contact Numbers: +91-99117-75120 Follow us "We specialize in bringing you in-line with the real India - traditions, rituals, beauty, heauty, heritage, festivals, adventures,wild life, carnivals and many more different facets of our country- INDIA". TRAVEL PLAN Dear Traveler Greetings from ALifetimeTrip Thank you for choosing us for your travel needs. Please find herewith all the relevant details (Itinerary, Accommodation) for your trip to Kolkata, Mayapur & Nabadwip.Kindly take a moment to review these. The travel plan is totally customizable. Please reach your tour planner and ask for changes that you would like to incorporate in your vacation. We value your business and look forward to assist you. Detailed Itinerary Tour Itinerary: Kolkata(2N)-Nabadwip(2N) Day 1: Kolkata Arrival to Nabadwip Arrival & welcome to Kolkata. The City of Joy. Meet & greet with our representative at Kolkata airport or Railway station & proceed to Nabadwip. Visit ISCKON Temple of Mayapur. Evening is free for leisure. Overnight stay at Nabadwip. Day 2: Nabadwip & Mayapur Trip After breakfast proceed to visit Conch Shell Handicraft of Nabadwip and Samudragar and its Treasure Trove of handloom Sarees. Also visit Ballal Mound, which is a reminiscent of Bengal king Ballal Sen and the tomb of Chand Kazi etc. Overnight stay at Nabadwip. Day 3: Nabadwip to Kolkata After breakfast check out from the hotel and transfer to Kolkata. Visit Town Hall, Indian Museum, St. Paul Cathedral, Victoria Memorial, and Mother House etc. Reach Kolkata & transfer to your respective hotel & overnight stay in Kolkata. Day 4: Kolkata Sightseeing After breakfast starts for full day tour of Kolkata surrounding - Drive through Howrah Bridge & visit to Belur Math. -

+91-99117-75120 TRAVEL PLAN Detailed Itinerary

Website: www.alifetimetrip.co.in Email: [email protected] Contact Numbers: +91-99117-75120 Follow us "We specialize in bringing you in-line with the real India - traditions, rituals, beauty, heauty, heritage, festivals, adventures,wild life, carnivals and many more different facets of our country- INDIA". TRAVEL PLAN Dear Traveler Greetings from ALifetimeTrip Thank you for choosing us for your travel needs. Please find herewith all the relevant details (Itinerary, Accommodation) for your trip to Excursion to Gangasagar.Kindly take a moment to review these. The travel plan is totally customizable. Please reach your tour planner and ask for changes that you would like to incorporate in your vacation. We value your business and look forward to assist you. Detailed Itinerary Tour Itinerary: Kolkata(3N) Day 1: Arrival at Kolkata Arrival & welcome to Kolkata, The City of Joy. At airport or Railway station, our representative will meet you & transfer to your respective hotel. On arrival check in to the hotel for refreshment. Then start city tour of Kolkata- Visit-Drive pass BBD Bagh, Writers Building, GPO, Raj Bhavan, Eden Garden, Akashbani Bhawan, High Court etc. Evening is free for leisure or you can enjoy shopping at local market (at your own). Overnight stay at Kolkata. Day 2: Kolkata Sightseeing After breakfast starts for full day tour of Kolkata surrounding - Drive through Howrah Bridge & visit to Belur Math. Drive through Vivekananda Setu & side view of Nivedita setu & to visit Dakshineswar Kali Temple etc. Overnight stay at the hotel. Day 3: Kolkata - Gangasagar - Kolkata After Breakfast full day excursion to Gangasagar - An island in the confluence of river Ganga & embayment of Bengal & well known for Kapil Muni Ashram which is advised to be a great devout significance. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

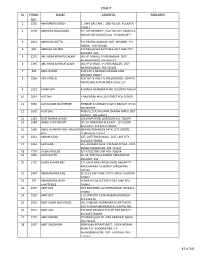

Sl Form No. Name Address Remarks

STARLIT SL FORM NAME ADDRESS REMARKS NO. 1 2235 ABHIMANYU SINGH 2, UMA DAS LANE , 2ND FLOOR , KOLKATA- 700013 2 1998 ABHISHEK MAJUMDER R.P. APPARTMENT , FLAT NO-303 PRAFULLA KANAN (W) KOLKATA-101 P.S-BAGUIATI 3 1922 ABHRANIL DUTTA P.O-PRAFULLANAGAR DIST-24PGS(N) , P.S- HABRA , PIN-743268 4 860 ABINASH HALDER 139 BELGACHIA EAST HB-6 SALT LAKE CITY KOLKATA -106 5 2271 ABU HENA MONIRUL ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI, P.S-REJINAGAR DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 6 1395 ABU HENA SAHINUR ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI , P.S-REGINAGAR , DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 7 446 ABUL HASAN B 32 1AH 3 MIAJAN OSTAGAR LANE KOLKATA 700017 8 3286 ADA AFREEN FLAT NO 9I PINES IV GREENWOOD SONATA NEWTOWN ACTION AREA II KOL 157 9 1623 ADHIR GIRI 8 DURGA CHANDRA ROAD KOLKATA 700014 10 2807 AJIT DAS 6 RAJENDRA MULLICK STREET KOL-700007 11 3650 AJIT KUMAR MUKHERJEE SHIBBARI K,S ROAD P.O &P.S NAIHATI DT 24 PGS NORTH 12 1602 AJOY DAS PO&VILL SOUTH GARIA CHARAK MATH DIST 24 PGS S PIN 743613 13 1261 AJOY KUMAR GHOSH 326 JAWPUR RD. DUMDUM KOL-700074 14 1584 AKASH CHOUDHURY DD-19, NARAYANTALA EAST , 1ST FLOOR BAGUIATI , KOLKATA-700059 15 2460 AKHIL CHANDRA ROY MNJUSRI 68 RANI RASHMONI PATH CITY CENTRE ROY DURGAPUR 713216 16 2311 AKRAM AZAD 227, DUTTABAD ROAD, SALT LAKE CITY , KOLKATA-700064 17 1441 ALIP JANA VILL-KHAMAR CHAK P.O-NILKUNTHIA , DIST- PURBA MIDNAPORE PIN-721627 18 2797 ALISHA BEGUM 5/2 B DOCTOR LANE KOL-700014 19 1956 ALOK DUTTA AC-64, PRAFULLA KANAN KRISHNAPUR KOLKATA -101 20 1719 ALOKE KUMAR DEY 271 SASHI BABU ROAD SAHID NAGAR PO KANCHAPARA PS BIZPUR 24PGSN PIN 743145 21 3447 -

7D6n Kolkata Golden Triangle Tour

Highlights: Explore the best highlights of North India. Delhi the political hub nerve center of India – an amazing amalgamation of various Indian culture. Delhi is where history has given way to modernity without loosing its identity. Agra the city of Taj Mahal the greatest monument of love a man ever built for his love and Jaipur the capital Rajasthan which culturally and historically one of the most richest region of India. Day 01 Singapore-Kolkata (-/L/D) Depart: FRI & SUN only. G8 36 – SIN/CCU 0450/0625 Upon arrival at Kolkata airport, meet our representative at the airport. The representative would arrange transfer to hotel. (Check-in time 1200 Hrs.- Early check-in subject to availability of rooms) Tourist attraction to visit includes the Victoria Memorial Hall, Science City, Metro Rail, Memorial Hall, Mother Teresa Home, China Town, Rabindra Setu, and Vidyasagar Setu. Lunch at local restaurant. Later in the evening take a leisure walk to the markets of Kolkata. Dinner and overnight in hotel. Day 02 Kolkata-Delhi (B/L/D) G8 102 CCU/DEL 1420/1650 Breakfast. Morning visit Dakshineswar Kali Temple. Continue visit to Belur Math. After lunch proceed to airport. Transfer to airport to board flight to Delhi- 1420/1650 Hrs. G8 102. Upon arrival at Delhi, transfer to hotel. Dinner and overnight in hotel. Day 03 Delhi-Agra (B/L/D) Breakfast. Half day tour of New Delhi. New Delhi: India’s capital, an important gateway into the country. Visit Lutyen’s Delhi-drive past President’s palace and also known as Rashtrapati Bhawan, India gate, a World War I memorial. -

Aesthetics of Dakhineswar Temple: an Empirical Study on the Temple Architecture Through the Lens of Contemporary Time

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 Received: 23-11-2019; Accepted: 25-12-2019 www.socialsciencejournal.in Volume 6; Issue 1; January 2020; Page No. 100-108 Aesthetics of dakhineswar temple: An empirical study on the temple architecture through the lens of contemporary time Animesh Manna1, Soumita Chatterjee2 1 Assistant Professor, Department of History, Shyampur Shiddheswari Mahavidyalaya Ajodhya, Howrah, West Bengal, India 2 Guest Lecturer, Department of Anthropology, Shyampur Shiddheswari Mahavidyalaya Ajodhya, Howrah, West Bengal, India Abstract The term temple is an oblivious expression of Hinduism which is most often unheeded. The temple architecture generally exhibits the social condition, material culture as well as the ideological paradigms of a particular community. Dakhineswar Kali temple has more than hundred year’s heritage records in West Bengal and India too. The present study is an attempt to understand how different cultural patterns and impact of various Indian historical time period embedded in an architectural style. For this paper, the data were collected through observation, interview methods. This research reveals the impact of Indo- Islamic style as a form of ‘ratna’ or towered structure, European influence as a presence of flat roof temple pattern and ‘aat- chala’ form expressing the Bengal Temple Terracotta style. Furthermore, the presence of skywalk, car parking area, specially designed security witnessing the touches of modernization through the shades of cultural heritage. Keywords: architecture, Dakhineswar, modernization, temple 1. Introduction Northern style, the ‘Dravida’ or the Southern style and the Every stone is sacred and everyone is devotee in Hinduism. -

A Day in Kolkata"

"A Day in Kolkata" Realizado por : Cityseeker 14 Ubicaciones indicadas Mother House "A Glimpse into the Finest Life" 54 Bose Road is one of the most famous addresses in Kolkata and an important stopover for every tourist visiting the city. The building aptly called Mother House is the headquarters of the Missionaries of Charity, Mother Teresa's vision to spread hope and love to the despair. Even today, Mother Teresa’s sisters of charity, clad in their trademark blue- by Hiroki Ogawa bordered saris, continue to carry forward her legacy. Visitors can pay their respects at the Mother's tomb and visit the museum displaying objects from her routine life – sandals and a worn-out bowl that stand as true reflections of her simplicity. Invoking peace and a range of different emotions, this place allows you to catch a glimpse into the life of one of the finest human beings to have ever lived. +91 33 245 2277 www.motherteresa.org/ 54/A A.J.C. Bose Road, Missionaries of Charity, Calcuta Raj Bhavan "Royal Residence" During the colonial rule, the Britishers erected magnificent structures and palatial residences, that often replicated buildings and government offices back in England. Raj Bhavan is one of such splendid heritage landmarks in the city of Kolkata. Spread across 27 acres, the wrought iron gates and imposing lions atop, create a majestic allure to the whole place and draw a clear line of distinction between the powerful rulers and the powerless common man. It continued to be the official residence of Governor- Generals and Viceroy until Kolkata ceased to be the capital of India and Delhi came into prominence. -

Government of West Bengat District Health & Family Wetfare Samiti Office of the Chief Medicat Officer of Heait North 24 Parg

GOVERNMENTOFWEST BENGAT DISTRICTHEALTH & FAMILYWETFARE SAMITI OFFICEOF THECHIEF MEDICAT OFFICER OF HEAIT NORTH24 PARGANAS,BARASAT PHONENO. 2552312?,tAX NO.25624789 /258425 'itrit fli[q-q rrqn t:'JiE *E:r+uP:*'l E-MAILlD: [email protected] / 2&*&- 2*12 [email protected] MemoNo. DH&FWS/NRHM/20 12/97 4 Dote: 27t'September 2012 To TheExecuiive Directol WestBengolStote heolth & FomilyWelfore Somity Deportmentof Heolth& FomilyWelfore Governmentof WestBengol Sir. With reference to your communicotion Vide Memo No. H/SFWB/20P-O3-2O12/55212)11,doted, 14.O9.2012regording recruitment under Adolescent Heolth Progromme (RCH-ll), enclosed pleose find the list of 152condidotes for the postof LodyCounselor in the districiof North24 Porgonosmentioning the oddress of the condidotes,dote & venue of exominoiion. .Youore olsorequested to disploythe website(www.north24porgcncs.gov.in) of the districtNorth 24 Porgonosfor furthercommunicotion of both the lody counselor& ProgrommeAssociote. (The sort list condidotesnome isolso send herewith) You ore requestedto kindly orronge to disploythe soid list in the officiol website of Swosthyo Bhowon. tr),/ Dy. Chief Health - III MemoNo.- DH&FWS/NRHM/20 12/97 4 / 1(5) Date>27h September, 20 12 CopyForwarded for information& necessaryaction l) The CommissionerFW & Secretary,Govt. of WestBengal 2) The SFWO,Addl. DHS, Dept of FW, Govt.of WestBengal 3) The ChiefMedical Officer of Health,North 24 Parganas 4) TheManager - HR Cell, WBSH&FW Samiti,Swasthya Bhawan 5) GuardFile \rv' Dy. Chief Health - III North 24 Short Listed Candidate for Written Examination of Lady Counsellor District - North 24 Parganas Date of Examination - 14.10.2012, Time of Arrival - 10.30 AM. Duration of Examination - 11.00 A.M.