FIELDWORK REPORTS Excavations at the Later Prehistoric Site Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group (TAG) on Polio Eradication in Pakistan

Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group (TAG) on Polio Eradication in Pakistan Karachi & Islamabad, Pakistan, 8-12 January 2019 Acronyms AFP Acute Flaccid Paralysis bOPV Bivalent Oral Polio Vaccine C4E Communication for Eradication CBV Community-Based Vaccination CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CHW Community Health Workers cVDPV2 Circulating Vaccine Derived Polio Virus Type 2 CWDP Central Development Working Party DC Deputy Commissioner DPCR District Polio Control Room DPEC District Polio Eradication Committee EI Essential Immunization ES Environnemental Sample EOC Emergency Operations Centers EPI Expanded Programme on Immunization EV Entero-Virus FCVs Female Community Vaccinators FGD Focus Group Discussion FRR Financial Resource Requirements GAVI Global Alliance for Vaccines GB Gilgit Baltistan GOP Government of Pakistan GPEI Global Polio Eradication Initiative HRMP High-Risk Mobile Populations ICM Intra-campaign Monitoring IPV Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine KP Khyber Pakhtunkhwa KPTD Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Tribal Districts LEAs Law Enforcing Agents LPUCs Low Performing Union Councils LQAS Lot Quality Assurance Sampling mOPV Monovalent Oral Polio Vaccine NA Not Available Children NA3 Not Available Children Out-of-District NEAP National Emergency Action Plan NEOC National Emergency Operation Center NID National Immunization Day NGO Non-Governmental Organization NPAFP Non-Polio Acute Flaccid Paralysis NTF National Task Force NPMT National Polio Management Team N-STOP National Stop Transmission of Poliomyelitis PC1 Planning Commission -

DFG Part-L Development Settled

DEMANDS FOR GRANTS DEVELOPMENTAL EXPENDITURE FOR 2020–21 VOL-III (PART-L) GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA FINANCE DEPARTMENT REFERENCE TO PAGES DFG PART- L GRANT # GRANT NAME PAGE # - SUMMARY 01 – 23 50 DEVELOPMENT 24 – 177 51 RURAL AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT 178 – 228 52 PUBLIC HEALTH ENGINEERING 229 – 246 53 EDUCATION AND TRAINING 247 – 291 54 HEALTH SERVICES 292 – 337 55 CONSTRUCTION OF IRRIGATION 338 – 385 CONSTRUCTION OF ROADS, 56 386 – 456 HIGHWAYS AND BRIDGES 57 SPECIAL PROGRAMME 457 – 475 58 DISTRICT PROGRAMME 476 59 FOREIGN AIDED PROJECTS 477 – 519 ( i ) GENERAL ABSTRACT OF DISBURSEMENT (SETTLED) BUDGET REVISED BUDGET DEMAND MAJOR HEADS ESTIMATES ESTIMATES ESTIMATES NO. -

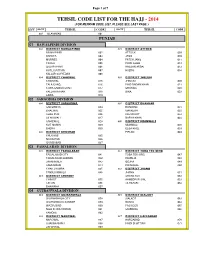

Tehsil Code List for the Hajj

Page 1 of 7 TEHSIL CODE LIST FOR THE HAJJ - 2014 (FOR MEHRAM CODE LIST, PLEASE SEE LAST PAGE ) DIV DISTT TEHSIL CODE DISTT TEHSIL CODE 001 ISLAMABAD 001 PUNJAB 01 RAWALPINDI DIVISION 002 DISTRICT RAWALPINDI 003 DISTRICT ATTOCK RAWALPINDI 002 ATTOCK 009 KAHUTA 003 JAND 010 MURREE 004 FATEH JANG 011 TAXILA 005 PINDI GHEB 012 GUJAR KHAN 006 HASSAN ABDAL 013 KOTLI SATTIAN 007 HAZRO 014 KALLAR SAYYEDAN 008 004 DISTRICT CHAKWAL 005 DISTRICT JHELUM CHAKWAL 015 JHELUM 020 TALA GANG 016 PIND DADAN KHAN 021 CHOA SAIDAN SHAH 017 SOHAWA 022 KALLAR KAHAR 018 DINA 023 LAWA 019 02 SARGODHA DIVISION 006 DISTRICT SARGODHA 007 DISTRICT BHAKKAR SARGODHA 024 BHAKKAR 031 BHALWAL 025 MANKERA 032 SHAH PUR 026 KALUR KOT 033 SILAN WALI 027 DARYA KHAN 034 SAHIEWAL 028 009 DISTRICT MIANWALI KOT MOMIN 029 MIANWALI 038 BHERA 030 ESSA KHEL 039 008 DISTRICT KHUSHAB PIPLAN 040 KHUSHAB 035 NOOR PUR 036 QUAIDABAD 037 03 FAISALABAD DIVISION 010 DISTRICT FAISALABAD 011 DISTRICT TOBA TEK SING FAISALABAD CITY 041 TOBA TEK SING 047 FAISALABAD SADDAR 042 KAMALIA 048 JARANWALA 043 GOJRA 049 SAMUNDARI 044 PIR MAHAL 050 CHAK JHUMRA 045 012 DISTRICT JHANG TANDLIANWALA 046 JHANG 051 013 DISTRICT CHINIOT SHORE KOT 052 CHINIOT 055 AHMEDPUR SIAL 053 LALIAN 056 18-HAZARI 054 BHAWANA 057 04 GUJRANWALA DIVISION 014 DISTRICT GUJRANWALA 015 DISTRICT SIALKOT GUJRANWALA CITY 058 SIALKOT 063 GUJRANWALA SADDAR 059 DASKA 064 WAZIRABAD 060 PASROOR 065 NOSHEHRA VIRKAN 061 SAMBRIAL 066 KAMOKE 062 016 DISTRICT NAROWAL 017 DISTRICT HAFIZABAD NAROWAL 067 HAFIZABAD 070 SHAKAR GARH 068 PINDI BHATTIAN -

ADP 2021-22 Planning and Development Department, Govt of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Page 1 of 446 NEW PROGRAMME

ONGOING PROGRAMME SECTOR : Agriculture SUB-SECTOR : Agriculture Extension 1.KP (Rs. In Million) Allocation for 2021-22 Code, Name of the Scheme, Cost TF ADP (Status) with forum and Exp. upto Beyond S.#. Local June 21 2021-22 date of last approval Local Foreign Foreign Cap. Rev. Total 1 170071 - Improvement of Govt Seed 288.052 0.000 230.220 23.615 34.217 57.832 0.000 0.000 Production Units in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. (A) /PDWP /30-11-2017 2 180406 - Strengthening & Improvement of 60.000 0.000 41.457 8.306 10.237 18.543 0.000 0.000 Existing Govt Fruit Nursery Farms (A) /DDWP /01-01-2019 3 180407 - Provision of Offices for newly 172.866 0.000 80.000 25.000 5.296 30.296 0.000 62.570 created Directorates and repair of ATI building damaged through terrorist attack. (A) /PDWP /28-05-2021 4 190097 - Wheat Productivity Enhancement 929.299 0.000 378.000 0.000 108.000 108.000 0.000 443.299 Project in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Provincial Share-PM's Agriculture Emergency Program). (A) /ECNEC /29-08-2019 5 190099 - Productivity Enhancement of 173.270 0.000 98.000 0.000 36.000 36.000 0.000 39.270 Rice in the Potential Areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Provincial Share-PM's Agriculture Emergency Program). (A) /ECNEC /29-08-2019 6 190100 - National Oil Seed Crops 305.228 0.000 113.000 0.000 52.075 52.075 0.000 140.153 Enhancement Programme in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Provincial Share-PM's Agriculture Emergency Program). -

Public Information Officers Contact List

Public Information Officers Contact List S.NO NAME DESIGNATION DEPARTMENT Sub-Department DISTRICT TELEPHONE CELL NUMBER EMAIL 1 Mr. Muhammad Riaz DEO (M) Education ELEMENTARY EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Abbottabad 0992-9310102 3335060225 [email protected] 2 Miss. Samina Altaf DEO (F) Education ELEMENTARY EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Abbottabad 0992-342314 3 Dr. Fazle Rehman Director Livestock, Abbottabad Agriculture DIRECTORATE OF AGRICULTURE (EXTENSION) Abbottabad 0992-382628 4 Dr. Pervez Principal Research Officer/Regional Director Agriculture DIRECTOR GENERAL (RESEARCH) LIVESTOCK & DAIRY DEVELOPMENT Abbottabad 0992-383763 0345-8566012 5 Mr. Waqas Ashraf Assistant Public Prosecutor Law DISTRICT ABBOTTABAD Abbottabad 0992-9310383 0300-9110884 [email protected] 6 Mr. Mussamer Shah Assistant Manager (Legal) Forest Development Corporation Forest & Environment DISTRICT ABBOTTABAD Abbottabad 0992-380897 7 Mr. Naeem Khan Additional Deputy Commissioner Revenue Deputy Commissioner Abbottabad 0992-9310207 [email protected] 8 Mr. Jahanzeb Khan Deputy Director Small Industrial Estate Small Industrial Estate Abbottabad 0992-383770 9 Mr. Zaffar Ali Khan DFO, Gallis, Abbottabad Forest & Environment Environment Abbottabad 0992-9310306 [email protected] 10 Mr. Faiq Khan DFO, Wildlife, Abbottabad Forest & Environment Environment Abbottabad 0992-9310323 0302-193344 [email protected] 11 Mr. Khabir Muhammad Police Hazara Division, Hazara Abbottabad 0992-9310516 12 Mr. Jawad Khan Sub Divisional Officer Irrigation Irrigation Sub Divisional Abbotabad Abbottabad 0992-9310246 0346-9577518 13 Mr. Baber Shamrez Research Officer Agriculture Agriculture Research System Abbottabad 0992-380873 0345-5300126 14 Muhammad Saleem Raza District Sports Officer Abbottabad and Torghar Sports Sports Department Abbottabad 0992-9310224 0334-9067114 15 Abdul Malik Khan DSP/FRP Police Police department Abbottabad 0992-9310020 0300-5796002 16 Waheed Gul District Zakat Officer Zakat and Ushar Zakat & Usher Dept . -

Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group on Polio Eradication in Pakistan

Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group on Polio Eradication in Pakistan Islamabad, Pakistan 30 November – 1 December 2017 Acronyms AFP Acute Flaccid Paralysis bOPV Bivalent Oral Polio Vaccine CBV Community-Based Vaccination CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cVDPV2 Circulating Vaccine Derived Polio Virus Type 2 DPCR District Polio Control Room ES Environmental Sample EOC Emergency Operating Centers EV Entero-Virus FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FCVs Female Community Vaccinators GB Gilgit Baltistan GPEI Global Polio Eradication Initiative HRMP High-Risk Mobile Populations IPV Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine KP Khyber Pakhtunkhwa LEAs Law Enforcing Agents LPUCs Low Performing Union Councils LQAS Lot Quality Assurance Sampling mOPV Monovalent Oral Polio Vaccine NEOC National Emergency Operation Center NID National Immunization Day NGO Non-Governmental Organization NPAFP Non-Polio Acute Flaccid Paralysis PCM Post Campaign Monitoring PC1 Planning Commission 1 PEOC Provincial Emergency Operation Center RI Routine Immunization RSP Religious Support Persons SIA Supplementary Immunization Activity SOP Standard Operating Procedure TAG Technical Advisory Group UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund VDPV Vaccine Derived Polio Virus WHO World Health Organization WPV Wild Polio Virus 1 Table of Contents Acronyms 1 Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Progress 11 Pakistan Program ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Molecular Prevalence of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

International Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences Vol. 4(5), pp. 123-127, July 2012 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/IJMMS DOI: 10.5897/IJMMS12.095 ISSN 2006-9723 ©2012 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Molecular prevalence of Hepatitis B virus infection in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Zia Ur Rahman Awan1*, Abdul Haleem Shah1, Sanaullah Khan2, Saeed Ur Rahman1 and Hafiz Munib Ur Rahman1 1Department of Biological Sciences, Gomal University Dera Ismail Khan, Pakistan. 2Department of Zoology, Kohat University of Sciences and Technology Kohat, Pakistan. Accepted 1 June, 2012 Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major health problem in the developing countries including Pakistan. This study aimed to investigate various risk factors and prevalence of HBV in different areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Pakistan. A total of 1439 individuals (1021 males and 418 females) suspected for hepatitis B infection were screened for HBsAg. All the samples were blindly analyzed for HBV DNA by nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Of the total, 49.5% were found positive for HBsAg. Of these HBsAg positive patients, 83.03% were confirmed for HBV DNA. Of the 726 HBsAg negative individuals, 37 (24 males and 13 females) were found positive for HBV DNA. 629 HBV DNA positive individuals include 70.43% male and 29.57% female. Higher prevalence rate (16.53%) was observed in Malakand and lowest (13.35%) in Mardan. Mostly young people with age 16 to 30 years were infected as compared to other age group. Risk factors observed in HBV positive individuals were unhygienic barber practice, blood transfusion, general and dental surgery, unsafe injection and sharing personal items. -

Abbreviations and Acronyms

P ART III] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., NOV. 21, 2019 1945 ISLAMABAD, FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2019 PART III Other Notifications, Orders, etc. ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN NOTIFICATION Islamabad, the 26th November, 2019 No. F. 12(3)/2019-E/Rolls(3).—In exercise of the powers conferred by section 29 of the Election Act, 2017, the Election Commission of Pakistan is pleased to appoint for the purpose of receiving and deciding claims, objections and applications of correction of votes, the officers specified in column 2 of the schedule below, to be the Revising Authorities in the Province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, for the electoral areas falling within the jurisdiction mentioned against each in the corresponding entry in the column 3 of the said schedule. (1945) Price: Rs. 5.00 [1856(2019)/Ex.Gaz.] 1946 THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., NOV. 29, 2019 [PART III SCHEDULE Sl. Revising Authority Jurisdiction No. 1 2 3 Regional Election Commissioner, 1. District Peshawar (including Sub-Division Hassan Khel) 1. Peshawar Division 2 District Charsadda 3. District Nowshera Regional Election Commissioner, 1. District Mardan 2. District Swabi 2. Mardan Division 1. District Kohat (including Sub-Division Dara Adam Khel) Regional Election Commissioner, 3. Kohat Division 2. District Karak 3. District Hangu 4. District Okrakzai 5. District Kurrum 1. Bannu (including Sub-Division Wazir) Regional Election Commissioner, 4. 2. District Lakki Marwat (including Sub-Division Bhettani) Bannu Division 3. District North Wazirstan 1. District D. I. Khan (including Sub-Division Darazanda) Regional Election Commissioner, 5. D.I. Khan Division 2. District Tank (including Sub-Division Jandola) 3. -

4582 Opt.Pdf, PDF, 5.95MB

4'5 2J fL),1u ') jry 2 -LLL) jj )1 -i )11P J 7Yt1L)' cJb'L&J) ) 2019 _2O13 7 uestion No. 2355 Form Mst. Shagufta Malik, MPA Details of Purchased vehicles for Secretaries, Additional Secretaries, Deputy Secretaries, Commissioners, Deputy Commissioners, Additional Commissioners, Assistant Commissioners etc. during financial year 2013-2019. The Govt. of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Administration Department had purchased nineteen (19) no. of vehicles by approval of the Competent Authority (Annex-I, II, III) during the year 2013-2019. Furthermore, allotment (handing/taking) of these vehicles are placed at Annex-IV. The Details of each vehicle is tabulated as below: S.NO VEHICLE NO MAKE/TYPE/ENGINE CAPACITY MODEL ALLOTED TO Amount Purchased from: Mr. Bakhtiar (BPS-20) 1 AB-1606 Toyota Corolla GLI 1300 CC 2018 Toyota khyber Motors -Ring Road Special Secretry Esatblishment Peshawar - Mr. Shahid Sohail Khan (BPS-19) 2 AB-2210 Toyota khyber Motors Ring Road Toyota Corolla GLI 1300 cc 2018 Additional Secretary Administration 1,989,500/- Peshawar Department AB-2214 Mr. NasirAman(BPS-19) Toyota khyber Motors Ring Road Toyota Corolla GLI 1300 cc 2018 1,989,500/- Additional Secretary (Regulation) Peshawar 4 AB-1879 Capt.(R) Abdur Rehman BS-18) Toyota khyber Motors Ring Road Toyota Corolla GLI 1300 cc 2018 1,989,500/- P50 to chief Secretary Peshawar 5 AB-2212 Syed Jamal uddin Shah (BS-20) Toyota khyber Motors Ring Road Toyota Corolla GLI 1300 cc 2018 1,989,500/- Secretary Establishment Peshawar 6 Toyota khyber Motors Ring Road AB-2213 Toyota Corolla GLI 1300 -

Final Research Paper Industrial Policy (Khyber

FINAL RESEARCH PAPER INDUSTRIAL POLICY (KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA) PAKISTAN SUBMITTED BY: Syed Zaigham Kazmi SUBMITTED TO: Dr. Velma Grover This document is purely an academic exercise submitted in partial fulfillment for the Masters program of Engineering & Public Policy 1 CONTENT ABSTRACT………………………………………….. 3 INTRODUCTION…………………………………… 3 ABOUT KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA…………….. 4 INDUSTRIAL BACKGROUND……………………. 8 PRESENT STATUS…………………………………. 12 OBJECTIVE…………………………………………. 14 CONSIDERATION…………………………………. 15 RECENT POLICIES………………………………… 16 INDUSTRIAL SURVEY…………………………….. 25 CHALLENGES & STRATEGY……………………. 27 OTHER POLICY OPTIONS………………………... 31 CONCLUSSION……………………………………… 33 APPENDIX……………………………………………. 35 ACRONYMS KP: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa NMC: National Management Consultant SDA: Sarhad Development Authority BSS: Business Support Services SEZ: Special Economic Zones IGC: International Growth Center FATA: Federally Administrated Tribal Area KPCCI: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Chamber of Commerce and Industry SMEDA: Small & Medium Enterprises Development Authority 2 ABSTRACT: To development more sustainable society as industry in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and needs to better understand how to respond to environmental, social and economic challenges and transform industrial behavior. At the center of the industrial sustainability, the purpose is to develop knowledge and tools that help accelerate the transition towards a sustainable industrial system. Industrial sustainability now appears to be moving up the management agenda in many organizations. [1] Industry is a key player in the -

Request for Proposal

GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY Request for Proposal For Consultancy Services for “UPDATION OF REVISED ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA 3rd Floor, SDU Building, Khyber Road, Peshawar. EPA/RFP/______/______ Request for Proposal (RFP) Dear Sir/Madam, You are requested to submit a proposal for Updating of revised environmental Profile of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). 1. Under regular budget object head A03919 others for the services rendered as per enclosed Terms of Reference (TOR). The offeror(s)should submit single proposal for the assignment mentioned below: Expected Outputs and Deliverables 1. Collection of Primary Data at district level of all Industrial units/factories mentioned in Schedule(IEE/EIA/ developmental work, Crush plants, Marble units, Poultry farms, Brick Kilns, Housing Schemes etc along with GIS Coordinates ,GIS Mapping , Status of Pollution Control System, NEQS Status ,Status of Environmental approval from EPA KP, location of the unit ( within or outside industrial estate). 2. Collection of secondary Data of forestation, deforestation, BTS Towers and Population. 3. Collection of primary data in all 35 districts on Environmental Segments i.e. Air, Water, soil, mentioned in the TORS. GIS Mapping/GIS data at the district and provincial level. 4. GIS data on prescribed Survey Form (provided by EPA). 5. Deliver GIS database sets, metadata, and cartographic productions to EPA KP. 6. All GIS and other data and work would be property of EPA and should not be utilized anywhere else without prior permission from the EPA. 7. Workshop after submission of each divisional data. 8. Final workshop after submission of final report. 9. -

Adp 2021-2022

ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2021-22 PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA JUNE, 2021 ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2021-22 GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT http://www. pndkp.gov.pk Annual Development Programme 2021-22 Table of Contents S.No. Description Page No. 1 Abstract-I i 2 Abstract-II ii 3 Abstract-III iii 4 Abstract-IV ix 5 Abstract-V x 6 Abstract-VI xi 7 Agriculture 1 8 Auqaf, Hajj 41 9 Board of Revenue 53 10 Districts ADP 63 11 DWSS 65 12 E&SE 84 13 Energy & Power 107 14 Environment 118 15 Establishment & Administration 121 16 Excise, Taxation & NC 125 17 Finance 127 18 Food 130 19 Forestry 134 20 Health 146 21 Higher Education 167 22 Home 186 23 Housing 200 24 Industries 203 25 Information 223 26 Labour 227 27 Law & Justice 228 28 Local Government 235 29 Mines & Minerals 245 30 Multi Sectoral Dev. 249 31 Population Welfare 271 32 Public Private Partnership 274 33 Relief and Rehab. 292 34 Roads 299 35 Science Technology & Information Technology 364 36 Social Welfare 372 37 Sports, Tourism 380 38 Transport 405 39 Urban Development 408 40 Water 419 41 Annex-I - List of Foreign Aided Projects - 42 Annex-II - District Development Plan - Annual Development Programme 2021-22 Sector Wise Ongoing / New Programme Ongoing New Total S # Sector % No. Alloc. No. Alloc. No. Alloc. 1 Agriculture 115 6,036.154 20 2,311.847 135 8,348.001 3.67 2 Auqaf, Hajj, Religious & Minority Affairs 30 798.161 19 201.840 49 1,000.001 0.44 3 Board of Revenue 37 1,019.402 5 246.598 42 1,266.000