Identification and Characterization of TPRKB Dependency in TP53 Deficient Cancers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congenital Cataracts–Facial Dysmorphism–Neuropathy

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases BioMed Central Review Open Access Congenital Cataracts – Facial Dysmorphism – Neuropathy Luba Kalaydjieva* Address: Western Australian Institute for Medical Research and Centre for Medical Research, The University of Western Australia, Hospital Avenue, WA 6009 Nedlands, Australia Email: Luba Kalaydjieva* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 29 August 2006 Received: 11 July 2006 Accepted: 29 August 2006 Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2006, 1:32 doi:10.1186/1750-1172-1-32 This article is available from: http://www.OJRD.com/content/1/1/32 © 2006 Kalaydjieva; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Congenital Cataracts Facial Dysmorphism Neuropathy (CCFDN) syndrome is a complex developmental disorder of autosomal recessive inheritance. To date, CCFDN has been found to occur exclusively in patients of Roma (Gypsy) ethnicity; over 100 patients have been diagnosed. Developmental abnormalities include congenital cataracts and microcorneae, primary hypomyelination of the peripheral nervous system, impaired physical growth, delayed early motor and intellectual development, mild facial dysmorphism and hypogonadism. Para-infectious rhabdomyolysis is a serious complication reported in an increasing number of patients. During general anaesthesia, patients with CCFDN require careful monitoring as they have an elevated risk of complications. CCFDN is a genetically homogeneous condition in which all patients are homozygous for the same ancestral mutation in the CTDP1 gene. Diagnosis is clinical and is supported by electrophysiological and brain imaging studies. -

The Title of the Article

Mechanism-Anchored Profiling Derived from Epigenetic Networks Predicts Outcome in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Xinan Yang, PhD1, Yong Huang, MD1, James L Chen, MD1, Jianming Xie, MSc2, Xiao Sun, PhD2, Yves A Lussier, MD1,3,4§ 1Center for Biomedical Informatics and Section of Genetic Medicine, Department of Medicine, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637 USA 2State Key Laboratory of Bioelectronics, Southeast University, 210096 Nanjing, P.R.China 3The University of Chicago Cancer Research Center, and The Ludwig Center for Metastasis Research, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637 USA 4The Institute for Genomics and Systems Biology, and the Computational Institute, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637 USA §Corresponding author Email addresses: XY: [email protected] YH: [email protected] JC: [email protected] JX: [email protected] XS: [email protected] YL: [email protected] - 1 - Abstract Background Current outcome predictors based on “molecular profiling” rely on gene lists selected without consideration for their molecular mechanisms. This study was designed to demonstrate that we could learn about genes related to a specific mechanism and further use this knowledge to predict outcome in patients – a paradigm shift towards accurate “mechanism-anchored profiling”. We propose a novel algorithm, PGnet, which predicts a tripartite mechanism-anchored network associated to epigenetic regulation consisting of phenotypes, genes and mechanisms. Genes termed as GEMs in this network meet all of the following criteria: (i) they are co-expressed with genes known to be involved in the biological mechanism of interest, (ii) they are also differentially expressed between distinct phenotypes relevant to the study, and (iii) as a biomodule, genes correlate with both the mechanism and the phenotype. -

![Computational Genome-Wide Identification of Heat Shock Protein Genes in the Bovine Genome [Version 1; Peer Review: 2 Approved, 1 Approved with Reservations]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8283/computational-genome-wide-identification-of-heat-shock-protein-genes-in-the-bovine-genome-version-1-peer-review-2-approved-1-approved-with-reservations-88283.webp)

Computational Genome-Wide Identification of Heat Shock Protein Genes in the Bovine Genome [Version 1; Peer Review: 2 Approved, 1 Approved with Reservations]

F1000Research 2018, 7:1504 Last updated: 08 AUG 2021 RESEARCH ARTICLE Computational genome-wide identification of heat shock protein genes in the bovine genome [version 1; peer review: 2 approved, 1 approved with reservations] Oyeyemi O. Ajayi1,2, Sunday O. Peters3, Marcos De Donato2,4, Sunday O. Sowande5, Fidalis D.N. Mujibi6, Olanrewaju B. Morenikeji2,7, Bolaji N. Thomas 8, Matthew A. Adeleke 9, Ikhide G. Imumorin2,10,11 1Department of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria 2International Programs, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 14853, USA 3Department of Animal Science, Berry College, Mount Berry, GA, 30149, USA 4Departamento Regional de Bioingenierias, Tecnologico de Monterrey, Escuela de Ingenieria y Ciencias, Queretaro, Mexico 5Department of Animal Production and Health, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria 6Usomi Limited, Nairobi, Kenya 7Department of Animal Production and Health, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria 8Department of Biomedical Sciences, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY, 14623, USA 9School of Life Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, 4000, South Africa 10School of Biological Sciences, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, 30032, USA 11African Institute of Bioscience Research and Training, Ibadan, Nigeria v1 First published: 20 Sep 2018, 7:1504 Open Peer Review https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.16058.1 Latest published: 20 Sep 2018, 7:1504 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.16058.1 Reviewer Status Invited Reviewers Abstract Background: Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are molecular chaperones 1 2 3 known to bind and sequester client proteins under stress. Methods: To identify and better understand some of these proteins, version 1 we carried out a computational genome-wide survey of the bovine 20 Sep 2018 report report report genome. -

Total Synthesis and Chemoproteomics Connect Curcusone Diterpenes with Oncogenic Protein BRAT1

Total Synthesis and Chemoproteomics Connect Curcusone Diterpenes with Oncogenic Protein BRAT1 Chengsen Cui1†, Brendan G. Dwyer2†, Chang Liu1, Daniel Abegg2, Zhongjian Cai1, Dominic Hoch2, Xianglin Yin1, Nan Qiu2, Jieqing Liu3, Alexander Adibekian2*, Mingji Dai1* 1Department of Chemistry and Center for Cancer Research, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, United States 2Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, 130 Scripps Way, Jupiter, FL 33458, United States 3School of Medicine, Huaqiao University, Quanzhou 362021, P. R. China Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M. D. (email: [email protected]) and A. A. ([email protected]) †Contributed equally. Abstract: Natural products are an indispensable source of lifesaving medicine, but natural product-based drug discovery often suffers from scarce natural supply and unknown mode of action. The study and development of anticancer curcusone diterpenes fall into such a dilemma. Meanwhile, many biologically- validated disease targets are considered “undruggable” due to the lack of enzymatic activity and/or predicted small molecule binding sites. The oncogenic BRCA1-associated ATM activator 1 (BRAT1) belongs to such an “undruggable” category. Here, we report our synthetic and chemoproteomics studies of the curcusone diterpenes that culminate in an efficient total synthesis and the identification of BRAT1 as a cellular target. We demonstrate for the first time that BRAT1 can be inhibited by a small molecule (curcusone D), resulting in impaired DNA damage response, reduced cancer cell migration, potentiated activity of the DNA damaging drug etoposide, and other phenotypes similar to BRAT1 knockdown. 1 Natural products have been valuable sources and inspirations of lifesaving drug molecules1. Their accumulated evolutionary wisdom together with their structural novelty and diversity makes them unparalleled for novel therapeutic development. -

Gene Targeting Therapies (Roy Alcalay)

Recent Developments in Gene - Targeted Therapies for Parkinson’s Disease Roy Alcalay, MD, MS Alfred and Minnie Bressler Associate Professor of Neurology Division of Movement Disorders Columbia University Medical Center Disclosures Funding: Dr. Alcalay is funded by the National Institutes of Health, the DOD, the Michael J. Fox Foundation and the Parkinson’s Foundation. Dr. Alcalay receives consultation fees from Genzyme/Sanofi, Restorbio, Janssen, and Roche. Gene Localizations Identified in PD Gene Symbol Protein Transmission Chromosome PARK1 SNCA α-synuclein AD 4q22.1 PARK2 PRKN parkin (ubiquitin ligase) AR 6q26 PARK3 ? ? AD 2p13 PARK4 SNCA triplication α-synuclein AD 4q22.1 PARK5 UCH-L1 ubiquitin C-terminal AD 4p13 hydrolase-L1 PARK6 PINK1 PTEN-induced kinase 1 AR 1p36.12 PARK7 DJ-1 DJ-1 AR 1p36.23 PARK8 LRRK2 leucine rich repeat kinase 2 AD 12q12 PARK9 ATP13A2 lysosomal ATPase AR 1p36.13 PARK10 ? ? (Iceland) AR 1p32 PARK11 GIGYF2 GRB10-interacting GYF protein 2 AD 2q37.1 PARK12 ? ? X-R Xq21-q25 PARK13 HTRA2 serine protease AD 2p13.1 PARK14 PLA2G6 phospholipase A2 (INAD) AR 22q13.1 PARK15 FBXO7 F-box only protein 7 AR 22q12.3 PARK16 ? Discovered by GWAS ? 1q32 PARK17 VPS35 vacuolar protein sorting 35 AD 16q11.2 PARK18 EIF4G1 initiation of protein synth AD 3q27.1 PARK19 DNAJC6 auxilin AR 1p31.3 PARK20 SYNJ1 synaptojanin 1 AR 21q22.11 PARK21 DNAJC13 8/RME-8 AD 3q22.1 PARK22 CHCHD2 AD 7p11.2 PARK23 VPS13C AR 15q22 Gene Localizations Identified in PD Disorder Symbol Protein Transmission Chromosome PD GBA β-glucocerebrosidase AD 1q21 SCA2 -

Seq2pathway Vignette

seq2pathway Vignette Bin Wang, Xinan Holly Yang, Arjun Kinstlick May 19, 2021 Contents 1 Abstract 1 2 Package Installation 2 3 runseq2pathway 2 4 Two main functions 3 4.1 seq2gene . .3 4.1.1 seq2gene flowchart . .3 4.1.2 runseq2gene inputs/parameters . .5 4.1.3 runseq2gene outputs . .8 4.2 gene2pathway . 10 4.2.1 gene2pathway flowchart . 11 4.2.2 gene2pathway test inputs/parameters . 11 4.2.3 gene2pathway test outputs . 12 5 Examples 13 5.1 ChIP-seq data analysis . 13 5.1.1 Map ChIP-seq enriched peaks to genes using runseq2gene .................... 13 5.1.2 Discover enriched GO terms using gene2pathway_test with gene scores . 15 5.1.3 Discover enriched GO terms using Fisher's Exact test without gene scores . 17 5.1.4 Add description for genes . 20 5.2 RNA-seq data analysis . 20 6 R environment session 23 1 Abstract Seq2pathway is a novel computational tool to analyze functional gene-sets (including signaling pathways) using variable next-generation sequencing data[1]. Integral to this tool are the \seq2gene" and \gene2pathway" components in series that infer a quantitative pathway-level profile for each sample. The seq2gene function assigns phenotype-associated significance of genomic regions to gene-level scores, where the significance could be p-values of SNPs or point mutations, protein-binding affinity, or transcriptional expression level. The seq2gene function has the feasibility to assign non-exon regions to a range of neighboring genes besides the nearest one, thus facilitating the study of functional non-coding elements[2]. Then the gene2pathway summarizes gene-level measurements to pathway-level scores, comparing the quantity of significance for gene members within a pathway with those outside a pathway. -

Supplementary Information Integrative Analyses of Splicing in the Aging Brain: Role in Susceptibility to Alzheimer’S Disease

Supplementary Information Integrative analyses of splicing in the aging brain: role in susceptibility to Alzheimer’s Disease Contents 1. Supplementary Notes 1.1. Religious Orders Study and Memory and Aging Project 1.2. Mount Sinai Brain Bank Alzheimer’s Disease 1.3. CommonMind Consortium 1.4. Data Availability 2. Supplementary Tables 3. Supplementary Figures Note: Supplementary Tables are provided as separate Excel files. 1. Supplementary Notes 1.1. Religious Orders Study and Memory and Aging Project Gene expression data1. Gene expression data were generated using RNA- sequencing from Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC) of 540 individuals, at an average sequence depth of 90M reads. Detailed description of data generation and processing was previously described2 (Mostafavi, Gaiteri et al., under review). Samples were submitted to the Broad Institute’s Genomics Platform for transcriptome analysis following the dUTP protocol with Poly(A) selection developed by Levin and colleagues3. All samples were chosen to pass two initial quality filters: RNA integrity (RIN) score >5 and quantity threshold of 5 ug (and were selected from a larger set of 724 samples). Sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq with 101bp paired-end reads and achieved coverage of 150M reads of the first 12 samples. These 12 samples will serve as a deep coverage reference and included 2 males and 2 females of nonimpaired, mild cognitive impaired, and Alzheimer's cases. The remaining samples were sequenced with target coverage of 50M reads; the mean coverage for the samples passing QC is 95 million reads (median 90 million reads). The libraries were constructed and pooled according to the RIN scores such that similar RIN scores would be pooled together. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Figure S1. The functionality of the tagged Arp6 and Swr1 was confirmed by monitoring cell growth and sensitivity to hydeoxyurea (HU). Five-fold serial dilutions of each strain were plated on YPD with or without 50 mM HU and incubated at 30°C or 37°C for 3 days. Figure S2. Localization of Arp6 and Swr1 on chromosome 3. The binding of Arp6-FLAG (top), Swr1-FLAG (middle), and Arp6-FLAG in swr1 cells (bottom) are compared. The position of Tel 3L, Tel 3R, CEN3, and the RP gene are shown under the panels. Figure S3. Localization of Arp6 and Swr1 on chromosome 4. The binding of Arp6-FLAG (top), Swr1-FLAG (middle), and Arp6-FLAG in swr1 cells (bottom) in the whole chromosome region are compared. The position of Tel 4L, Tel 4R, CEN4, SWR1, and RP genes are shown under the panels. Figure S4. Localization of Arp6 and Swr1 on the region including the SWR1 gene of chromosome 4. The binding of Arp6- FLAG (top), Swr1-FLAG (middle), and Arp6-FLAG in swr1 cells (bottom) are compared. The position and orientation of the SWR1 gene is shown. Figure S5. Localization of Arp6 and Swr1 on chromosome 5. The binding of Arp6-FLAG (top), Swr1-FLAG (middle), and Arp6-FLAG in swr1 cells (bottom) are compared. The position of Tel 5L, Tel 5R, CEN5, and the RP genes are shown under the panels. Figure S6. Preferential localization of Arp6 and Swr1 in the 5′ end of genes. Vertical bars represent the binding ratio of proteins in each locus. -

Supplement 1 Microarray Studies

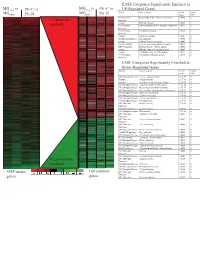

EASE Categories Significantly Enriched in vs MG vs vs MGC4-2 Pt1-C vs C4-2 Pt1-C UP-Regulated Genes MG System Gene Category EASE Global MGRWV Pt1-N RWV Pt1-N Score FDR GO Molecular Extracellular matrix cellular construction 0.0008 0 110 genes up- Function Interpro EGF-like domain 0.0009 0 regulated GO Molecular Oxidoreductase activity\ acting on single dono 0.0015 0 Function GO Molecular Calcium ion binding 0.0018 0 Function Interpro Laminin-G domain 0.0025 0 GO Biological Process Cell Adhesion 0.0045 0 Interpro Collagen Triple helix repeat 0.0047 0 KEGG pathway Complement and coagulation cascades 0.0053 0 KEGG pathway Immune System – Homo sapiens 0.0053 0 Interpro Fibrillar collagen C-terminal domain 0.0062 0 Interpro Calcium-binding EGF-like domain 0.0077 0 GO Molecular Cell adhesion molecule activity 0.0105 0 Function EASE Categories Significantly Enriched in Down-Regulated Genes System Gene Category EASE Global Score FDR GO Biological Process Copper ion homeostasis 2.5E-09 0 Interpro Metallothionein 6.1E-08 0 Interpro Vertebrate metallothionein, Family 1 6.1E-08 0 GO Biological Process Transition metal ion homeostasis 8.5E-08 0 GO Biological Process Heavy metal sensitivity/resistance 1.9E-07 0 GO Biological Process Di-, tri-valent inorganic cation homeostasis 6.3E-07 0 GO Biological Process Metal ion homeostasis 6.3E-07 0 GO Biological Process Cation homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Biological Process Cell ion homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Biological Process Ion homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Molecular Helicase activity 2.3E-06 0 Function GO Biological -

Teleological Role of L-2-Hydroxyglutarate

© 2020. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Disease Models & Mechanisms (2020) 13, dmm045898. doi:10.1242/dmm.045898 RESEARCH ARTICLE Teleological role of L-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase in the kidney Garrett Brinkley1, Hyeyoung Nam1, Eunhee Shim1,*, Richard Kirkman1, Anirban Kundu1, Suman Karki1, Yasaman Heidarian2, Jason M. Tennessen2, Juan Liu3, Jason W. Locasale3, Tao Guo4, Shi Wei4, Jennifer Gordetsky5, Teresa L. Johnson-Pais6, Devin Absher7, Dinesh Rakheja8, Anil K. Challa9 and Sunil Sudarshan1,10,‡ ABSTRACT insight into the physiological role of L2HGDH as well as mechanisms L-2-hydroxyglutarate (L-2HG) is an oncometabolite found elevated in that promote L-2HG accumulation in disease states. renal tumors. However, this molecule might have physiological roles that extend beyond its association with cancer, as L-2HG levels are KEY WORDS: L-2-hydroxyglutarate, L-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase, TCA cycle, PPARGC1A elevated in response to hypoxia and during Drosophila larval development. L-2HG is known to be metabolized by L-2HG dehydrogenase (L2HGDH), and loss of L2HGDH leads to elevated INTRODUCTION L-2HG levels. Despite L2HGDH being highly expressed in the kidney, Oncometabolites are small molecules that have been found elevated its role in renal metabolism has not been explored. Here, we report our in various malignancies. To date, these molecules include the findings utilizing a novel CRISPR/Cas9 murine knockout model, with tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates succinate and fumarate a specific focus on the role of L2HGDH in the kidney. Histologically, as well as both enantiomers of 2-hydroxyglutarate (D-2HG and L2hgdh knockout kidneys have no demonstrable histologic L-2HG) (Tomlinson et al., 2002; Baysal et al., 2000; Niemann and abnormalities. -

IL21R Expressing CD14+CD16+ Monocytes Expand in Multiple

Plasma Cell Disorders SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX IL21R expressing CD14 +CD16 + monocytes expand in multiple myeloma patients leading to increased osteoclasts Marina Bolzoni, 1 Domenica Ronchetti, 2,3 Paola Storti, 1,4 Gaetano Donofrio, 5 Valentina Marchica, 1,4 Federica Costa, 1 Luca Agnelli, 2,3 Denise Toscani, 1 Rosanna Vescovini, 1 Katia Todoerti, 6 Sabrina Bonomini, 7 Gabriella Sammarelli, 1,7 Andrea Vecchi, 8 Daniela Guasco, 1 Fabrizio Accardi, 1,7 Benedetta Dalla Palma, 1,7 Barbara Gamberi, 9 Carlo Ferrari, 8 Antonino Neri, 2,3 Franco Aversa 1,4,7 and Nicola Giuliani 1,4,7 1Myeloma Unit, Dept. of Medicine and Surgery, University of Parma; 2Dept. of Oncology and Hemato-Oncology, University of Milan; 3Hematology Unit, “Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda”, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan; 4CoreLab, University Hospital of Parma; 5Dept. of Medical-Veterinary Science, University of Parma; 6Laboratory of Pre-clinical and Translational Research, IRCCS-CROB, Referral Cancer Center of Basilicata, Rionero in Vulture; 7Hematology and BMT Center, University Hospital of Parma; 8Infectious Disease Unit, University Hospital of Parma and 9“Dip. Oncologico e Tecnologie Avanzate”, IRCCS Arcispedale Santa Maria Nuova, Reggio Emilia, Italy ©2017 Ferrata Storti Foundation. This is an open-access paper. doi:10.3324/haematol. 2016.153841 Received: August 5, 2016. Accepted: December 23, 2016. Pre-published: January 5, 2017. Correspondence: [email protected] SUPPLEMENTAL METHODS Immunophenotype of BM CD14+ in patients with monoclonal gammopathies. Briefly, 100 μl of total BM aspirate was incubated in the dark with anti-human HLA-DR-PE (clone L243; BD), anti-human CD14-PerCP-Cy 5.5, anti-human CD16-PE-Cy7 (clone B73.1; BD) and anti-human CD45-APC-H 7 (clone 2D1; BD) for 20 min.