Shifting the Geography of Reason in an Age of Disciplinary Decadence ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jean-Luc Nancy and the Deconstruction of Christianity By

Jean-Luc Nancy and the Deconstruction of Christianity by Tenzan Eaghll A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department for the Study of Religion University of Toronto ©Copyright by Tenzan Eaghll 2016 Jean-Luc Nancy and the Deconstruction of Christianity Tenzan Eaghll Doctor of Philosophy Department for the Study of Religion University of Toronto 2016 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the origins and development of the French philosopher Jean- Luc Nancy’s work on the “deconstruction of Christianity.” By situating Nancy's work in light of the broader Continental philosophical analysis of religion in the 20th Century, it argues that what Nancy calls the "deconstruction of Christianity" and the "exit from religion" is his unique intervention into the problem of metaphysical nihilism in Western thought. The author explains that Nancy’s work on religion does not provide a new “theory” for the study of religion or Christianity, but shows how Western metaphysical foundations are caught up in a process of decomposition that has been brought about by Christianity. For Nancy, the only way out of nihilism is to think of the world as an infinite opening unto itself, for this dis- encloses any transcendent principle of value or immanent notion of meaninglessness in the finite spacing of sense, and he finds the resources to think this opening within Christianity. By reading Christian notions like "God" and "creation ex nihilo" along deconstructive lines and connecting them with the rise and fall of this civilization that once called itself "Christendom," he attempts to expose "the sense of an absenting" that is both the condition of possibility for the West and what precedes, succeeds, and exceeds it. -

Habermas's Politics of Rational Freedom: Navigating the History Of

This is a repository copy of Habermas’s politics of rational freedom: Navigating the history of philosophy between faith and knowledge. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/162100/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Verovšek, P.J. (2020) Habermas’s politics of rational freedom: Navigating the history of philosophy between faith and knowledge. Analyse & Kritik, 42 (1). pp. 191-218. ISSN 0171-5860 https://doi.org/10.1515/auk-2020-0008 © 2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH. This is an author-produced version of a paper subsequently published in Analyse and Kritik. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Habermas’s Politics of Rational Freedom: Navigating the History of Philosophy between Faith and Knowledge* Peter J. Verovšek† Department of Politics & International Relations University of Sheffield Elmfield, Northumberland Road Sheffield, S10 2TU United Kingdom [email protected] ABSTRACT Despite his hostility to religion in his early career, since the turn of the century Habermas has devoted his research to the relationship between faith and knowledge. -

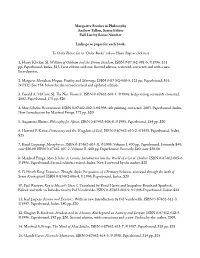

Marquette Studies in Philosophy Andrew Tallon, Series Editor Full List by Series Number

Marquette Studies in Philosophy Andrew Tallon, Series Editor Full List by Series Number Links go to pages for each book. To Order Please Go to “Order Books” tab on Home Page or click here 1. Harry Klocker, SJ. William of Ockham and the Divine Freedom. ISBN 0-87462-001-5. ©1996. 141 pp. Paperbound. Index. $15. First edition sold out. Second edition, reviewed, corrected and with a new Introduction. 2. Margaret Monahan Hogan. Finality and Marriage. ISBN 0-87462-600-5. 121 pp. Paperbound, $15. NOTE: See #34, below for the second revised and updated edition. 3. Gerald A. McCool, SJ. The Neo-Thomists. ISBN 0-87462-601-1. ©1994. 3rd printing, revised & corrected, 2003. Paperbound, 175 pp. $20 4. Max Scheler. Ressentiment. ISBN 0-87462-602-1.©1998. 4th printing, corrected, 2003. Paperbound. Index. New Introduction by Manfred Frings. 172 pp. $20 5. Augustine Shutte. Philosophy for Africa. ISBN 0-87462-608-0. ©1995. Paperbound. 184 pp. $20 6. Howard P. Kainz. Democracy and the ‘Kingdom of God.’ ISBN 0-87462-610-2. ©1995. Paperbound. Index. $25 7. Knud Løgstrup. Metaphysics. ISBN 0-87462-603-X. ©1995. Volume I. 400 pp. Paperbound. Formerly $40; now $20.00 ISBN 0-67462-607-2. Volume II. 400 pp. Paperbound. Formerly $40; now $20.00 8. Manfred Frings. Max Scheler. A Concise Introduction into the World of a Great Thinker. ISBN 0-87462-605-6. ©1996. Paperbound. Second edition, revised. Index. New Foreword by the author. $20 9. G. Heath King. Existence, Thought, Style: Perspectives of a Primary Relation, portrayed through the work of Søren Kierkegaard. -

Philosophy of Education

PHILOSOPHY OF EDUCATION phainomena 28 | 110-111 | November 2019 28 | 110-111 November PHAINOMENA Revija za fenomenologijo in hermenevtiko Journal of Phenomenology and Hermeneutics 28 | 110-111 | November 2019 Andrzej Wierciński & Andrej Božič (eds.): PHILOSOPHY OF EDUCATION Institute Nova Revija for the Humanities * Phenomenological Society of Ljubljana * In collaboration with: IIH International Institute for Hermeneutics Institut international d’herméneutique Ljubljana 2019 UDC 1 p-ISSN 1318-3362 e-ISSN 2232-6650 PHAINOMENA Revija za fenomenologijo in hermenevtiko Journal of Phenomenology and Hermeneutics Glavna urednica: | Editor-in-Chief: Andrina Tonkli Komel Uredniški odbor: | Editorial Board: Jan Bednarik, Andrej Božič, Tine Hribar, Valentin Kalan, Branko Klun, Dean Komel, Ivan Urbančič+, Franci Zore. Tajnik uredništva: | Secretary: Andrej Božič Mednarodni znanstveni svet: | International Advisory Board: Pedro M. S. Alves (University of Lisbon, Portugal), Babette Babich (Fordham University, USA), Damir Barbarić (University of Zagreb, Croatia), Renaud Barbaras (University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, France), Miguel de Beistegui (The University of Warwick, United Kingdom),Azelarabe Lahkim Bennani (Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Morocco), Rudolf Bernet (KU Leuven, Belgium), Petar Bojanić (University of Belgrade, Serbia), Philip Buckley (McGill University, Canada), Umesh C. Chattopadhyay (University of Allahabad, India), Gabriel Cercel (University of Bucharest, Romania), Cristian Ciocan (University of Bucharest, Romania), Ion Copoeru -

Download Download

Eurasian Dynamics: From Agrarian Axiality to the Connectivities of the Capitalocene Chris Hann ABSTRACTS Der einleitende Beitrag umreißt einen Rahmen, der die Dynamik der eurasischen Landmasse (flexibel definiert) in den Mittelpunkt der Weltgeschichte der letzten drei Jahrtausende stellt. Konzepte von Kulturraum, Zivilisation und Weltsystem werden kritisch überprüft. Besonderes Augenmerk gilt den Theorien der Achsenzeit, die sowohl religiöse als auch säkulare Varianten der Transzendenz umfassen, sowie deren Rolle bei der Legitimation politischer Institutionen. Diese Ansätze werden durch den Rückgriff auf den anthropo-archäologischen Materialismus von Jack Goody ergänzt, der die „alternierende Führung“ zwischen Ost und West betont. Der Fokus von Goody auf die wachsende städtische Differenzierung in den agrarischen Reichen der Bronzezeit kann erweitert werden, indem das Spektrum der Zivilisationen über die der intensi- ven Landwirtschaft hinaus ausgedehnt wird. Dieser Ansatz lässt sich mit theoretischen Erkennt- nissen von Karl Polanyi gewinnbringend kombinieren, um eine neue historische ökonomische Anthropologie anzuregen, die es uns ermöglicht, verschiedene Varianten des Sozialismus auf die Formen der sozialen Inklusion und der „imperialen sozialen Verantwortung“ zurückzufüh- ren, die in der Achsenzeit entstanden sind. Der Aufsatz argumentiert weiterhin, dass die eu- rasischen Zivilisationen, die die „große Dialektik“ zwischen Umverteilung und Marktaustausch hervorgebracht haben, angesichts der Widersprüche der heutigen neoliberalen politischen -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 517 Proceedings of the 6th Annual International Conference on Social Science and Contemporary Humanity Development (SSCHD 2020) On Value Goals of State Governance Modernization Xiaodong Li 1, 2,* 1 School of Marxism at Beijing Jiaotong University 2 CITIC Institute for Reform and Development Studies *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT As the value goals change as per the varying theme of the times, people desired for the unity and harmony during war and unrest years, but fought for democracy and freedom under great empire’s ruling. However, at present, as the social conflicts and economic stagnation occur, people are longing for communion and resurgence. The previous goals will become the subsequent tools, namely, the unity and harmony are the precondition to achieve the democracy and freedom, and the democracy and freedom is also the tool to realize the communion-resurgence. As endangering the economic development and social harmony, the western democracy and freedom are lagging behind our time, while the new age needs to construct the new state governance system carrying forward communion and resurgence. Keywords: State-Governance, Modernization, Unity-Harmony, Democracy & Freedom, Communion- resurgence. 1. INTRODUCTION governance [1]. On February 17th, 2014, Xi Jinping delivered an opening ceremony speech at the Workshop In 2020, we were not only shocked with the horrible of Learning and Implementing the Spirit of 3rd Plenary number of death and infections from the pandemic Session of the 18th CPCCC and comprehensively COVID-19, but also astonished with the distinct deepening the reform Attended by the Provincial-and- performance between the “decadent” Democracy and Ministerial-Level Leading Cadres, stressing that “the “responsive” authoritarianism, with American and general objective of comprehensively deepening the China as distinctive representative. -

Jaspers on Death Kiki Berk Southern New Hampshire University [email protected]

Volume 14, No 2, Fall 2019 ISSN 1932-1066 Jaspers on Death Kiki Berk Southern New Hampshire University [email protected] Abstract: This essay offers an analytic engagement with Karl Jaspers' philosophy of death. One of the central ideas in Jaspers' philosophy of death is that the way in which one confronts one's mortality and responds to the existential Angst it generates has profound existential significance. Particularly, Jaspers holds that one can achieve genuine authenticity only by facing up to one's mortality and by confronting it with courage. This essay situates Jaspers' philosophy of death within the current analytic philosophy of death and presents Jaspers' answers to its main questions including whether death is bad, whether one should fear death, whether death can be survived, and whether immortality is desirable. Keywords: Jaspers, Karl; death; mortality; Angst; authenticity; philosophy of death; analytic existentialism. Death has become a popular topic in contemporary The Existential Significance of Death analytic philosophy. Analytic existentialism addresses Viewed Analytically questions such as what happens at the time of death, whether death is bad for the one who dies, whether we In a nutshell, Jaspers' philosophy of death can be ought to fear death, and whether it is rational to want to understood as follows: What makes death existentially live forever. Unfortunately, this literature rarely engages significant is not the fact that one must die but rather the work of traditional existentialist philosophers such the confrontation with mortality that it generates. This as Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Simone de Beauvoir, confrontation gives rise to existential Angst, and it is Martin Heidegger, and Karl Jaspers. -

A Philosophical Understanding of Communication As Testimony Jessica Nicole Sturgess Purdue University

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Dissertations Theses and Dissertations January 2016 Saying the World Anew: A Philosophical Understanding of Communication as Testimony Jessica Nicole Sturgess Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations Recommended Citation Sturgess, Jessica Nicole, "Saying the World Anew: A Philosophical Understanding of Communication as Testimony" (2016). Open Access Dissertations. 1276. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/1276 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Graduate School Form 30 Updated 12/26/2015 PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Jessica N. Sturgess Entitled SAYING THE WORLD ANEW: A PHILOSOPHICAL UNDERSTANDING OF COMMUNICATION AS TESTIMONY For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Is approved by the final examining committee: Dr. Patrice Buzzanell Dr. Ramsey Eric Ramsey Co-chair Dr. Daniel W. Smith Co-chair Dr. Stacey Connaughton Dr. Calvin O. Schrag To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Thesis/Dissertation Agreement, Publication Delay, and Certification Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 32), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy of Integrity in Research” and the use of copyright material. Approved by Major Professor(s): Dr. Patrice Buzzanell and Dr. Daniel W. Smith Dr. Marifran Mattson 4/11/2016 Approved by: Head of the Departmental Graduate Program Date i SAYING THE WORLD ANEW: A PHILOSOPHICAL UNDERSTANDING OF COMMUNICATION AS TESTIMONY A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Jessica N. -

Toward a Holistic Interpretation of Karl Jaspers' Philosophy Endre Kiss Eötvös Loránd University Budapest, Hungary [email protected]

Volume 13, No 1, Spring 2018 ISSN 1932-1066 Toward a Holistic Interpretation of Karl Jaspers' Philosophy Endre Kiss Eötvös Loránd University Budapest, Hungary [email protected] Abstract: Of three typological characteristics that can be found in Karl Jaspers' thought, the first is the sequence of thorough transformations, if not revaluations, by which he changed existential thought. Jaspers separates into two parts the existential complex that traditionally has not only been unified but also constituted existential thought par excellence through its unity. By way of juxtaposing philosophical creation of meaning to existentiality, Jaspers goes beyond the boundaries of the fundamental self-identification of existential thought, for it is a trait of existential thought that it does not accept an assignment of extraneous meaning; in this respect the existential point of departure constitutes also a negative determination that heralds a provocative negation of any and all attempts for providing extraneous meaning. The second characteristic of Jaspers' philosophy that could hardly be integrated into existing philosophical typologies consists in the relation between science and philosophy. What is at stake here is not an exclusive primacy of philosophy at the expense of science. Both sides of the relation between science and philosophy are of a unique quality in the twentieth century, with equal relevance given to both. Additionally to the distinctive primacy of philosophy that is conspicuous, also the simultaneous and completely transparent normativity claim of this primacy is conspicuous. The third typological characteristic I would call perspectivism. At this juncture it ought to be already clear that this characteristic provisionally only shares the name with Friedrich Nietzsche's fundamental concept of philosophical perspectivism. -

KARL JASPERS (1883-1969) Hermann Horn1

The following text was originally published in Prospects: the quarterly review of comparative education (Paris, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education), vol. XXIII, no. 3/4, 1993, p. 721-739. ©UNESCO: International Bureau of Education, 2000 This document may be reproduced free of charge as long as acknowledgement is made of the source. KARL JASPERS (1883-1969) Hermann Horn1 Karl Jaspers lived in an age that witnessed far-reaching political changes. He grew up in the sheltered environment of a prosperous family with a democratic, liberal and conservative bent. His objections to the authoritarian, militaristic State and a society with a caste structure, which typified the German empire, are rooted in that background. Jaspers interpreted the outbreak of the First World War as a great fault line in the Western tradition. He believed that the Weimar Republic was threatened: politically by communism and fascism; socially by the mass consumption which was made possible by technology and machinery; and spiritually by the biased statements on man embodied in Marxism, psycho-analysis and racial theory. His life and work were at risk during the Hitler dictatorship. He was compulsorily retired in 1937. Publication of his works was banned in 1938. The entry of the American troops into Heidelberg on 1 April 1945 saved him and his Jewish wife from deportation to a concentration camp. Hope and concern mingled in his critical appraisal of the reconstruction and political process in the new Federal Republic of Germany. When he moved to Basle in Switzerland in 1948, he found a new home in a traditional European centre of liberty. -

Course Title Religion and Politics: an Old Inheritance of Fears and Facts

Année universitaire 2014/2015 Collège universitaire Semestre d’automne Course title Religion and Politics: an old Inheritance of Fears and Facts Lecturer Véronique ALBANEL Session1 : Introducing session Session 2: The "Axial Period": The diversity of religions versus the unity of Humanity Key words : Universal History, mytholgy; Confucius and Lao-Tseu (China), Bouddha (India), Zarathoustra (Persia), Prophets (Israël), philosophers (Greece) Key dates: -800 to -200 BC Karl Jaspers (1883-1969), The Origin and Goal of History. Yale University Press (New Haven, CT: 1953), pp. 1-21, 51-70. http://www.collegiumphaenomenologicum.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/Jaspers-The-Origin-and-Goal-of-History.pdf Session 3: JUDAISM (1): Time of persecution Keywords: YHWH, Torah, Talmud, Shema, halacha, theocracy, Haskalah. Key Dates: c. 1000 BC: Kingship of David; 587 BC: destruction of the first Temple and exile to Babylon; 70 AD: fall of Jerusalem and destruction of the Temple. Founding Text: Deuteronomy 6: 4-9 (Shema Israel). Moses Maimonides (1135-1204), "The Epistle on Martyrdom", in Epistles of Maimonides: Crisis and Leadership (The Jewish Publication Society: Philadelphia, 1985), p. 15-22 and 22-34 (especially p.30-34). http://books.google.fr/books?id=7zAlxRzcUoEC&pg=PA13&lpg=PA13&dq=maimonide+the+epistle+of+martyrdom&source=bl&ots= NYbh1sBns&sig=ioj2qp2CYX4FlSQHVqQ0G2Q3R0s&hl=fr&sa=X&ei=INLQU8bbMaaw0QWfwICgDA&ved=0CB4Q6AEwAA#v=on epage&q=maimonide%20the%20epistle%20of%20martyrdom&f=false Session 4: JUDAISM (2): The Holocaust, Zionism and universalism Keywords: Zionism, Eretz Israel, election, messianism, Diaspora Jewry. Key Dates: 1099: the crusaders took Jerusalem. Massacre of the Jewish population; 1939-1945: the Holocaust; 1948: Proclamation of the State of Israel. -

Simone De Beauvoir

H-France Review Volume 13 (2013) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 13 (August 2013), No. 130 Margaret A. Simons and Marybeth Timmerman, eds., Simone de Beauvoir. Political Writings. Urbana- Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2012. 384 pp. $42.00 U.S. (cl). ISBN-10: 0252036948. Review by Tove Pettersen, University of Oslo. Simone de Beauvoir. Political Writings is the latest volume in the University of Illinois Press’s monumental Beauvoir Series, a seven-volume collaborative book project, edited by Margaret A. Simons and Sylvie Le Bon de Beauvoir. The aim of the series is to make available scholarly English translations of Beauvoir's writings. Most of the texts presented have previously been difficult to access; some because they were not translated into English, others because they were published in newspapers and editions that are now out of circulation. Some have not been published before. Simons and Le Bon have organized Beauvoir’s writings thematically, with philosophical, literary, political and feminist texts collected in each volume (the latter is not published yet). Additionally, the Beauvoir Series includes two volumes of Beauvoir’s Diary (a third is to be published). These volumes underlay her autobiographical writings, and also interestingly prefigure many ideas more fully developed in Beauvoir’s later works. The Beauvoir Series covers more than fifty years of writings, demonstrating her theoretical development and growing commitment to ethical and political questions of her time. At the same time, an impressive consistency with regard to her basic philosophical ideas and values is displayed. In addition to being mandatory reading for all Beauvoir scholars, the analyses carried out are unique and provocative, also in context with our contemporary issues.