Alamo, Page 89.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson Quiz 1 the Alamo and Goliad DIRECTIONS: Matching Match Each Item with Its Description

NAME______________________________________________ DATE ___________________ CLASS _____________ Lesson Quiz 1 The Alamo and Goliad DIRECTIONS: Matching Match each item with its description. 1. river between Texas and Mexico A. Matamoros 2. abandoned mission used as a fortress B. Rio Grande 3. site where the Alamo is located C. Alamo 4. General Urrea led Mexican troops here D. San Antonio 5. Mexican city near the mouth of the Rio Grande E. Goliad DIRECTIONS: Multiple Choice Indicate the answer choice that best answers the question. 6. What were Santa Anna’s ultimate goals? A. to capture the Tejanos and repeal the Constitution of 1824 B. to defeat the rebels in Texas and regain control of the territory C. to hold talks with the rebels to reach a peaceful settlement D. to recruit Texas frontiersmen to his army and rebuild the Alamo 7. What caused a political division among the Texas forces? A. Some wanted to attack Matamoros, and others wanted to invade Mexico. B. Some wanted to hold the Alamo, and others wanted to hold Goliad. C. Some wanted to support Mexican Federalists, and others wanted to declare independence from Mexico. D. Some were led by Sam Houston, and others were led by Santa Anna. 8. How were James Bowie and Davy Crockett similar? A. Both volunteered to fight in Texas. C. Both served as Texas politicians. B. Both left the Alamo before the battle. D. Both were from Ohio. 9. Why couldn’t the Texas forces prepare effectively for Santa Anna’s invasion? A. Most volunteers had joined for the adventure and weren’t serious soldiers. -

Chapter 10: the Alamo and Goliad

The Alamo and Goliad Why It Matters The Texans’ courageous defense of the Alamo cost Santa Anna high casualties and upset his plans. The Texas forces used the opportunity to enlist volunteers and gather supplies. The loss of friends and relatives at the Alamo and Goliad filled the Texans with determination. The Impact Today The site of the Alamo is now a shrine in honor of the defenders. People from all over the world visit the site to honor the memory of those who fought and died for the cause of Texan independence. The Alamo has become a symbol of courage in the face of overwhelming difficulties. 1836 ★ February 23, Santa Anna began siege of the Alamo ★ March 6, the Alamo fell ★ March 20, Fannin’s army surrendered to General Urrea ★ March 27, Texas troops executed at Goliad 1835 1836 1835 1836 • Halley’s Comet reappeared • Betsy Ross—at one time • Hans Christian Andersen published given credit by some first of 168 stories for making the first American flag—died 222 CHAPTER 10 The Alamo and Goliad Compare-Contrast Study Foldable Make this foldable to help you compare and contrast the Alamo and Goliad—two important turning points in Texas independence. Step 1 Fold a sheet of paper in half from side to side. Fold it so the left edge lays about 1 2 inch from the right edge. Step 2 Turn the paper and fold it into thirds. Step 3 Unfold and cut the top layer only along both folds. This will make three tabs. Step 4 Label as shown. -

Texas Revolution Heating up •Get the Handouts Off the Table

Texas Revolution Heating Up •Get the handouts off the table. Write your name on it, fold it and keep it in your Alamo journal. •You need your profile sheets from yesterday. JUMPSTART: Read through the vocabulary list, you will have a test on these words tomorrow! Mark any that you need to review for the test and study!! Texas Revolution Heating Up Analyze the map from the background essay and discuss some of the challenges that the Mexican army might have faced in February of 1836. Texas Revolution Heating Up Write your name and class period on the back cover of your Alamo journal. Using your biography sheet from yesterday, write the name of the person you chose on the cover of your Alamo journal. Inside on the back of the front cover, write the details of your defender. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7xVx1ozrB7c Texas Revolution Timeline 1835 Oct. - General de Cos, acting under the orders of President Santa Anna, fortified the Alamo shortly after his arrival in San Antonio at the head of a small army. Dec. 10- General Cos and about 1,200 troops surrendered the Alamo to a volunteer Texan Army of fewer than 400 after a fierce battle for the city. 1836 Jan. 6- Colonel James Neill, commander of the Alamo, reported to the acting governor that he had 104 men, but they lacked food or clothing. Jan. 7- General Santa Anna and his army arrived at Saltillo, 365 miles from San Antonio. Jan. 14- Col. Neill wrote to Gen. Sam Houston, “Men in field four months. -

Battle of the Alamo 1 Battle of the Alamo

Battle of the Alamo 1 Battle of the Alamo The Battle of the Alamo (February 23 – March 6, 1836) was a pivotal event in the Texas Revolution. Following a 13-day siege, Mexican troops under President General Antonio López de Santa Anna launched an assault on the Alamo Mission near San Antonio de Béxar (modern-day San Antonio, Texas). All but two of the Texian defenders were killed. Santa Anna's perceived cruelty during the battle inspired many Texians—both Texas settlers and adventurers from the United States—to join the Texian Army. Buoyed by a desire for revenge, the Texians defeated the Mexican Army at the Battle of San Jacinto, on April 21, 1836, ending the revolution. Several months prior, Texians had driven all Mexican troops out of Mexican Texas. Approximately 100 Texians were then garrisoned at the Alamo. The Texian force grew slightly with the arrival of reinforcements led by eventual Alamo co-commanders James Bowie and William B. Travis. On February 23, approximately 1,500 Mexican troops marched into San Antonio de Béxar as the first step in a campaign to re-take Texas. For the next 12 days the two armies engaged in several skirmishes with minimal casualties. Aware that his garrison could not withstand an attack by such a large force, Travis wrote multiple letters pleading for more men and supplies, but fewer than 100 reinforcements arrived. In the early morning hours of March 6, the Mexican Army advanced on the Alamo. After repulsing two attacks, Texians were unable to fend off a third attack. -

Mapping-Texas-History-Colonization-To

INTRODUCTION TO SECOND EDITION The Alamo's Texas Maps for Teachers recognizes that history and geography are inseparable. This project was conceived after listening to teachers voice their concerns that current maps detailing Texas early history were inadequate for their needs. These new maps have been designed by educators for educators. A textual description for each map was written by Dr. Richard B. Winders, Historian & Curator for the Alamo. Dr. Donald S. Frazier, Professor of History at McMurry University in Abilene, Texas, produced the maps. The two educators have worked together on other projects for publishers Houghton Mifflin and Macmillan Reference. Texas Maps for Teachers has several different uses: It is a supplemental reader for teachers unfamiliar with Texas History. The comprehensive overview of important events and themes should be useful to any teacher. Overhead transparencies of the maps it can be produced for use in the classroom by scanning them into a computer and printing them onto commercially available transparency film. Used in combination with the textual descriptions, Texas Maps for Teachers can be used as a mini-textbook for Texas history from 1700 through 1850. The Alamo would like to thank several individuals who contributed their time by reviewing and commenting on this project at various stages. Dr. Ron Tyler, Executive Director of the Texas State Historical Association, offered valuable suggestions that were incorporated into the text and maps. Two teacher in San Antonio's North East Independent School District provided input from their respective grade levels: Barbara Yost, Windcrest Elementary School and Michael Bailey, Omar N. Bradley Middle School. -

Salsa2docprod 1..2

By:AAPhillips H.R.ANo.A258 RESOLUTION 1 WHEREAS, Residents of Fannin County are gathering at the 2 Texas State Capitol on February 13, 2013, to celebrate Fannin 3 County Day, and this occasion provides an opportunity to recognize 4 the rich history and significant accomplishments of this attractive 5 part of the Lone Star State; and 6 WHEREAS, The first nonnative settlements in the area that 7 would become Fannin County were established in 1836, the year Texas 8 won its independence from Mexico; when the county was formed the 9 following year, it took its name from Colonel James Walker Fannin, 10 Jr., a commander in the Texas revolutionary army, who had been 11 killed in the Goliad Massacre; Bonham, the county seat, was named 12 for another hero of the Texas Revolution, James Bonham, who died at 13 the Alamo and who is now honored with a statue at the county 14 courthouse; and 15 WHEREAS, A land of gently rolling hills that are bounded by 16 the Red River to the north, Fannin County provides good land for 17 farming and ranching, and those pursuits have been economic 18 mainstays since the county was established; today, cattle, corn, 19 wheat, milo, pecans, and hay are key products, and the many acres of 20 farmland in the county create a tranquil, pastoral landscape; other 21 industries, such as communications and manufacturing, help to 22 strengthen and diversify the economy; and 23 WHEREAS, Bonham, with a population of approximately 10,000, 24 is the county 's largest city; it was the hometown of Sam Rayburn, 83R5334 JGH-D 1 H.R.ANo.A258 1 the legendary Texas politician who was a member of Congress for 48 2 years and who still ranks as the longest-serving speaker of the U.S. -

Two Bowies, One Knife - Not Even Past

Two Bowies, One Knife - Not Even Past BOOKS FILMS & MEDIA THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN BLOG TEXAS OUR/STORIES STUDENTS ABOUT 15 MINUTE HISTORY "The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Tweet 122 Like THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Two Bowies, One Knife by Erika Bsumek and Penne Restad Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the Confederacy” Bowie was a “tall, raw-boned man with deep set eyes, fair hair, and an open and frank disposition.” Convivial and generous, he was a man, it was said, who loved music. That Bowie was James, not David. May 06, 2020 More from The Public Historian BOOKS America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States by Erika Lee (2019) Street sign for Bowie St., Austin, Texas, changed by a fan the week of January 10, 2016, when David Bowie died. Born in 1796, Jim Bowie was a speculator, a solider, and an adventurer who worked smuggling slaves with his brothers. Bowie was ambitious and scheming. He gambled at cards and knew how to fight. His weapon of choice, a very large hunting knife, secured him a reputation as the South’s most formidable knife fighter. He famously disemboweled one opponent in a brutal fight. Noah Smithwick, who was with him at the Battle of Concepción, called him “a born leader.” He eventually made his way to Texas and, like other legendary figures, died in 1836 defending the Alamo. April 20, 2020 More Books DIGITAL HISTORY Más de 72: Digital Archive Review https://notevenpast.org/two-bowies-one-knife/[6/16/2020 12:34:05 PM] Two Bowies, One Knife - Not Even Past March 16, 2020 More from Digital History FILMS & MEDIA Ayka (Dir: Sergei Dvortsevoy, 2018) James Bowie by George Peter Alexander Healey (c. -

Alamo Primary Sources

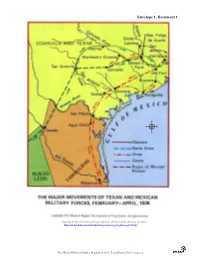

Envelope 1, Document 1 Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/atlas_texas/tex_mex_forces_1836.jpg Fort Worth ISD Social Studies Department 2013, Texas History Unit 5 resources Envelope 1, Document 2 Map of the Alamo showing the "Ground plan compiled from drawings by Capt. B. Green Jameson, Texan Army, January, 1826,Col. Ignacio de Labastida, Mexican Army, March, 1836, Capt. Ruben M. Potter, United States Army, 1841." http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth30285/m1/1/ Fort Worth ISD Social Studies Department 2013, Texas History Unit 5 resources http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/texas-maps-1.htm Envelope 2, Document 3 Fort Worth ISD Social Studies Department 2013, Texas History Unit 5 resources Defenders of the Alamo - http://www.thealamo.org/history/the-1836-battle/the-defenders/index.html Envelope 2, Document 4 Juan Abamillo, San Antonio James W. Garrand, La. James Nowlan, Ireland R. Allen James Girard Garrett, Tenn. George Pagan, Miss. Mills DeForrest Andross, Vermont John E. Garvin Christopher Parker, Miss. Micajah Autry, N.C. John E. Gaston. Ky. William Parks, N.C. Juan A. Badillo, San Antonio James George Richardson Perry Peter James Bailey, Ky. John Camp Goodrich, Tenn. Amos Pollard, Mass. Isaac G. Baker, Ark. Albert Calvin Grimes, Ga. John Purdy Reynolds, Pa. William Charles M. Baker, Mo. Jose Maria Guerrero, Laredo, Tex. Thomas H. Roberts John J. Ballentine James C. Gwynne, England James Robertson, Tenn. Richard W. Ballantine, Scotland James Hannum Isaac Robinson, Scotland John J. Baugh, Va John Harris, Ky. James M. Rose, Va. -

"James Bowie", a Hero of the Alamo

F 390 .B85 Copy 1 Jli Willi m^ ^*'i?j^-^ '''' ' ,(>', V'. > ^^/* ':''<^^^":'>^' ^60 JAMES BOWIE "JAMES BOWIE" A HERO OF THE ALAMO BY EVELYN BROGAN AUTHOR OF ••The Old Spanish Trail." SAN ANTONIO. TEXAS Theodore Kunzman"<,^^»l Printer & Publisher 1922 COPYRIGHT 1922 BY EVELYN BROGAN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FEB 14 72 ©C1A656775 TO The Heroes of the Alamo. PREFACE. James Bowie, a hero of the Alamo, and one of the most noted characters not only of Texas but of the United States, was born in South Carolina in 1805 of pioneer American parents. While still a child they moved to New Orleans and there James Bowie grew to manhood. The famous "Bowie Knife" received its name from James Bowie. He or his brother (Rezin Bowie) was the inventor of it. Love of adventure, so strong in youths of the pioneer age, mani- fested itself in James Bowie and he came to Texas, then a Mexican state, about 1828. He spent much fruitless time in searching for the famous silver mine chronicled in the old Spanish Records, as being located near the site of the former San Saba Mission. Failing to find the mine, he settled in San Antonio de Bexar, where he mar- ried Miss Ursula de Veramendi^ the daughter of Vice Governor Juan Martin de Veramendi, of Texas. Their beautiful home, the Vera- mendi Palace located on Soledad Street, was the center of Spanish hospitality and culture in the early days of San Antonio. The fam- ous old Veramendi Palace has since been torn down to make room for a modern building much to the regret of tourists and loyal citi- zens of old San Antonio. -

History Makers Second Was a Company of About 180 Volunteers at the Alamo

CHAPTER 13 • SECTION 2 Juan Seguín (wahn seh•GEEN) led a band of 25 Tejanos in support of revolt. Also among the Texas volunteers were free African Americans, but the Texas army hardly existed. There were two small RESEARCH & forces ready to stand up to Santa Anna’s army. One Go online to explore WRITINGmore of the CENTER heated was a company of 420 men, led by James Fannin, debate at ClassZone.com stationed at Goliad, a fort in southeast Texas. The History Makers second was a company of about 180 volunteers at the Alamo. Headed by James Bowie and William Juan Seguín Travis, this small force also included such famous Find links to biographies of Juan Seguín frontiersmen as Davy Crockett. at the Research and Writing Center @ On February 23, 1836, Santa Anna’s troops ClassZone.com. An active military leader surrounded San Antonio. The next day, Mexicans for Texas during the Revolution, Seguín began their siege of the Alamo. Two nights later, led the only Tejano unit at the Battle of Travis scrawled a message to the world: “The enemy San Jacinto and commanded the army that has demanded surrender. I have answered . with a cannon shot. I shall never surrender or accepted Mexico’s surrender at San Antonio. retreat.” Juan Seguín, a Tejano, spoke Spanish, so He was elected to the Texas Senate, where he was chosen to carry the declaration through he fought to have the laws of the new enemy lines. Seguín got the message through to Republic of Texas written in Spanish. Seguín other Texas defenders. -

THE REAL RIPPER by William R

THE REAL RIPPER By William R. Williamson "The glory of the "knife-men" wearing proudly their ivory handled Bowies in embroidered sheaths has indeed faded. Nevertheless the traditional tales of the frontier - tales yet to be heard all over the Southwest - Bowie's knife has become nothing less than the American counter- part of King Arthur's "Excalibur" or of Sigmund's great sword "Gram" forged with runic rhymes by the dwarf smiths of the old Norse gods. And its origin is wrapped in multiplied legends as conflicting and fantastic as those that glorify the master weapons of the old world." (1) In addressing the society this morning on the subject of James Bowie and the Bowie knife what location could be more apropos than the queen city of the Mississippi delta, historic and colorful old New Orleans. It was in this area and in this city that Bowie spent his formative years. The New Orleans of Bowie's time was less than genteel, it had become the melting pot of every nation and every color. Gamblers, mulatto tradesmen, plantation men, filibusters, pirates, slave traders, river boatmen trod its streets and sampled its life. If arranged in a WILLIAM R. WILLIAMSON circle the saloons, bordellos, cabarets and hostelrys would have surrounded the entire city. One traveler wrote, "There is, perhaps, no place in the civilized world where the influence of the gospel is more needed than in New Orleans." Dr. Thomas Nichols said, "it is notorious that the worst Southerners are Northerners." Northern businessmen arrived at the St. Charles hotel in a state of highly aroused expectancy. -

Unit 5 Texas Revolution Notes.Pdf

Unit 5 Unrest and Revolt in Texas 1821-1836 Texas Revolution For these notes – you write the slides with the red titles!!! Timeline • 1824 – Mexican Constitution of 1824 • 1828 – Mier y Teran Report • April 6, 1830 – Law of April 6 • 1832 – Turtle Bayou Resolution • January 1834 – Austin’s Arrest • 1835- Battle of Gonzales • March 2, 1836 Declaration of Independence • February 23 – March 6, 1836 Battle of the Alamo • March 6, 1836 Fall of the Alamo • March 27, 1836 – Mass Execution of men at Goliad • April 21, 1836 Battle of San Jacinto • May 1836 Treaties of Velasco Important People • George Childress – chaired the committee in charge of writing the Texas Declaration of Independence • Lorenzo de Zavala – helped write the Texas Declaration of Independence and helped design the ad interim government at Washington-on-the Brazos; was elected Vice President of the new republic • James Fannin – led the Texans at Coleto Creek and surrendered to Urrea; later he was executed at Goliad by order of Santa Anna • Sam Houston – leader of the Revolutionary Army during the Texas Revolution • Antonio López de Santa Anna – dictator of Mexico, and military leader of the Mexican Army during the Texas Revolution • Juan Seguín – served with Travis at the Alamo, but survived because he was sent out as a messenger to warn Sam Houston about the events at the Alamo. He continued to serve under Sam Houston at the Battle of San Jacinto. • William B. Travis –military leader of the Texas forces at the Alamo; was killed by Mexican forces at the Alamo • James (Jim) Bowie - Pioneer, knife fighter, soldier, & military leader at the Alamo until he fell sick.