Reality and Subjectivity in Alan Moore's Providence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian SF News 28

NUMBER 28 registered by AUSTRALIA post #vbg2791 95C Volume 4 Number 2 March 1982 COW & counts PUBLISH 3 H£W ttOVttS CORY § COLLINS have published three new novels in their VOID series. RYN by Jack Wodhams, LANCES OF NENGESDUL by Keith Taylor and SAPPHIRE IN THIS ISSUE: ROAD by Wynne Whiteford. The recommended retail price on each is $4.95 Distribution is again a dilemna for them and a^ter problems with some DITMAR AND NEBULA AWARD NOMINATIONS, FRANK HERBERT of the larger paperback distributors, it seems likely that these titles TO WRITE FIFTH DUNE BOOK, ROBERT SILVERBERG TO DO will be handled by ALLBOOKS. Carey Handfield has just opened an office in Melbourne for ALLBOOKS and will of course be handling all their THIRD MAJIPOOR BOOK, "FRIDAY" - A NEW ROBERT agencies along with NORSTRILIA PRESS publications. HEINLEIN NOVEL DUE OUT IN JUNE, AN APPRECIATION OF TSCHA1CON GOH JACK VANCE BY A.BERTRAM CHANDLER, GEORGE TURNER INTERVIEWED, Philip K. Dick Dies BUG JACK BARRON TO BE FILMED, PLUS MORE NEWS, REVIEWS, LISTS AND LETTERS. February 18th; he developed pneumonia and a collapsed lung, and had a second stroke on February 24th, which put him into a A. BERTRAM CHANDLER deep coma and he was placed on a respir COMPLETES NEW NOVEL ator. There was no brain activity and doctors finally turned off the life A.BERTRAM CHANDLER has completed his support system. alternative Australian history novel, titled KELLY COUNTRY. It is in the hands He had a tremendous influence on the sf of his agents and publishers. GRIMES field, with a cult following in and out of AND THE ODD GODS is a short sold to sf fandom, but with the making of the Cory and Collins and IASFM in the U.S.A. -

The Unspeakable Oath Issues 1 & 2 Page 1

The Unspeakable Oath issues 1 & 2 Page 1 Introduction to The Annotated Unspeakable Oath ©1993 John Tynes This is a series of freely-distributable text files that presents the textual contents of early issues of THE UNSPEAKABLE OATH, the world’s premiere digest for Chaosium’s CALL OF CTHULHU ™ role-playing game. Each file contains the nearly-complete text from a given issue. Anything missing is described briefly with the file, and is missing either due to copyright problems or because the information has been or will be reprinted in a commercial product. Everything in this file is copyrighted by the original authors, and each section carries that copyright. This file may be freely distributed provided that no money is charged whatsoever for its distribution. This file may only be distributed if it is intact, whole, and unchanged. All copyright notices must be retained. Modified versions may not be distributed — the contents belong to the creators, so please respect their work. Abusing my position as editor and instigator of the magazine and this project, I have taken the liberty of adding comments to some of the contents where I thought I had something interesting or historically worth preserving to say. Yeah, right! – John Tynes, editor-in-chief of Pagan Publishing The Unspeakable Oath issues 1 & 2 Page 2 Table of Contents Introduction to The Annotated Unspeakable Oath...................................................................................2 Introduction to TUO 1.........................................................................................................................4 -

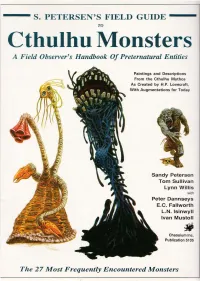

Cthulhu Monsters a Field Observer's Handbook of Preternatural Entities

--- S. PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO Cthulhu Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Paintings and Descriptions From the Cthulhu Mythos As Created by H.P. Lovecraft, With Augmentations for Today Sandy Petersen Tom Sullivan Lynn Willis with Peter Dannseys E.C. Fallworth L.N. Isinwyll Ivan Mustoll Chaosium Inc. Publication 5105 The 27 Most Frequently Encountered Monsters Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 t PETERSEN'S Field Guide To Cthulhu :Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Sandy Petersen conception and text TOIn Sullivan 27 original paintings, most other drawings Lynn ~illis project, additional text, editorial, layout, production Chaosiurn Inc. 1988 The FIELD GUIDe is p «blished by Chaosium IIIC . • PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO CfHUU/U MONSTERS is copyrighl e1988 try Chaosium IIIC.; all rights reserved. _ Similarities between characters in lhe FIELD GUIDE and persons living or dead are strictly coincidental . • Brian Lumley first created the ChJhoniwu . • H.P. Lovecraft's works are copyright e 1963, 1964, 1965 by August Derleth and are quoted for purposes of ilIustraJion_ • IflCide ntal monster silhouelles are by Lisa A. Free or Tom SU/livQII, and are copyright try them. Ron Leming drew the illustraJion of H.P. Lovecraft QIId tlu! sketclu!s on p. 25. _ Except in this p«blicaJion and relaJed advertising, artwork. origillalto the FIELD GUIDE remains the property of the artist; all rights reserved . • Tire reproductwn of material within this book. for the purposes of personal. or corporaJe profit, try photographic, electronic, or other methods of retrieval, is prohibited . • Address questions WId commel11s cOlICerning this book. -

May 2017 New Releases

MAY 2017 NEW RELEASES GRAPHIC NOVELS • MANGA • SCI-FI/ FANTASY • GAMES VORACIOUS : FEEDING TIME Hunting dinosaurs and secretly serving them at his restaurant, Fork & Fossil, has helped Chef ISBN-13: 978-1-63229-235-3 Nate Willner become a big success. But just when he’s starting to make something of his life, Price: $17.99 ($23.99 CAN) Publisher: Action Lab he discovers that his hunting trips with Captain Jim are actually taking place in an alternate Entertainment reality – an Earth where dinosaurs evolve into Saurians, a technologically advanced race that Writer: Markisan Naso rules the far future! Some of these Saurians have mysteriously started vanishing from Artist: Jason Muhr Cretaceous City and the local authorities are hell-bent on finding who’s responsible. Nate’s Page Count: 160 world is about to collide with something much, much bigger than any dinosaur he’s ever Format: Softcover, Full Color Recommended Age: Mature roasted. Readers (ages 16 and up) Genre: Science Fiction Collecting VORACIOUS: Feeding Time #1-5, this second volume of the critically acclaimed Ship Date: 6/6/2017 series serves up a colorful bowl of characters and a platter full of sci-fi adventure, mystery and heart! SELECTED PREVIOUS VOLUMES: • Voracious: Diners, Dinosaurs & Dives (ISBN-13 978-1-63229-165-3, $14.99) PROVIDENCE ACT 1 FINAL PRINTING HC Due to overwhelming demand, we offer one final printing of the Providence Act 1 Hardcover! ISBN-13: 978-1-59291-291-9 Alan Moore’s quintessential horror series has set the standard for a terrifying reinvention of Price: $19.99 ($26.50 CAN) Publisher: Avatar Press the works of H.P. -

The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France

names, Vol. 58 No. 3, September, 2010, 127–38 Teratonymy: The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France Lovecraft’s teratonyms are monstrous inventions that estrange the sound patterns of English and obscure the kinds of meaning traditionally associ- ated with literary onomastics. J.R.R. Tolkien’s notion of linguistic style pro- vides a useful concept to examine how these names play upon a distance from and proximity to English, so as to give rise to specific historical and cultural connotations. Some imitate the sounds and forms of foreign nomen- clatures that hold “weird” connotations due to being linked in the popular imagination with kabbalism and decadent antiquity. Others introduce sounds-patterns that lie outside English phonetics or run contrary to the phonotactics of the language to result in anti-aesthetic constructions that are awkward to pronounce. In terms of sense, teratonyms invite comparison with the “esoteric” words discussed by Jean-Jacques Lecercle, as they dimi- nish or obscure semantic content, while augmenting affective values and heightening the reader’s awareness of the bodily production of speech. keywords literary onomastics, linguistic invention, HP Lovecraft, twentieth- century literature, American literature, weird fiction, horror fiction, teratology Text Cult author H.P. Lovecraft is best known as the creator of an original mythology often referred to as the “Cthulhu Mythos.” Named after his most popular creature, this mythos is elaborated throughout Lovecraft’s poetry and fiction with the help of three “devices.” The first is an outlandish array of monsters of extraterrestrial origin, such as Cthulhu itself, described as “vaguely anthropoid [in] outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind” (1963: 134). -

Cthulhu Through the Ages Is Copyright © 2014 by Chaosium Inc

AUTHORS Mike Mason, Pedro Ziviani, John French, and Chad Bowser EDITING Mike Mason and Dustin Wright CARTOGRAPHY Stephanie McAlea INVESTIGATOR SHEETS Dean Engelhardt LAYOUT Nicholas Nacario COVER ILLUSTRATION Paul Carrick INTERIOR ILLUSTRATIONS Steven Gilberts, Sam Lamont, Florian Stitz, Paul Carrick, Goomi, Raymond Bayless, Nicholas Nacario. Some images were taken from Wikicommons and are in the public domain. THANKS TO Alan Bligh, John French, Matt Anderson, Penda Tomlin- son, and Dustin Wright. A special thanks to all of our 7th edition kickstarter backers who helped make this book possible. This supplement is best used with the roleplaying game CALL OF CTHULHU, available separately. Find more Chaosium Inc. products at www.chaosium.com Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 Cthulhu Through the Ages is copyright © 2014 by Chaosium Inc. All rights reserved. The names of public personalities may be referred to, but any resemblance of a scenario character to persons liv- ing or dead is strictly coincidental. Except in this publication and associated advertising, all illustrations for CTHULHU THROUGH THE AGES remain the property of the artists, who otherwise reserve all rights. This adventure pack is best used with the roleplaying game CALL OF CTHULHU, available separately. Find more Chaosium Inc. products at www.chaosium.com Item # 23146 ISBN10: 1568824386 ISBN13: 978-1568824383 Printed in USA Contents Introduction ������������������������������������������������������������������������ 5 Cthulhu Invictus ������������������������������������������������������������������ -

Lovecraft Patrons

Lovecraft Patrons Subclasses Specific to Various Great Old Ones of the Cthulhu Mythos By Zach Hitzeroth DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission Sampleof Wizards of the Coast. file ©2020 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057-0707, USA. Manufactured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 4 The Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, UK. Note on Expanded Spell Lists Player's Handbook Only Spells Spells marked with an asterisk are from Xanathar's 4th Level: fabricate Guide to Everything. If your DM does not allow these spells, alternate spells from the Player's Handbook can be found at the end of each subclass. Abhoth Also known as the Source of Uncleanliness, Abhoth is an Outer God depicted as an ooze or slime from which monsters and unnamable horrors crawl from. Followers of Abhoth tend to spread disease and carry oozes around with them to symbolize their patron. Expanded Spell List Abhoth lets you choose from an expanded list of spells when you learn a warlock spell. -

ENC 1145 3309 Chalifour

ENC 1145: Writing About Weird Fiction Section: 3309 Time: MWF Period 8 (3:00-3:50 pm) Room: Turlington 2349 Instructor: Spencer Chalifour Email: [email protected] Office: Turlington 4315 Office Hours: W Period 7 and by appointment Course Description: In his essay “Supernatural Horror in Fiction,” H.P. Lovecraft defines the weird tale as having to incorporate “a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.” This course will focus on “weird fiction,” a genre originating in the late 19th century and containing elements of horror, fantasy, science fiction, and the macabre. In our examination of weird authors spanning its history, we will attempt to discover what differentiates weird fiction from similar genres and will use several theoretical and historical lenses to examine questions regarding what constitutes “The Weird.” What was the cultural and historical context for the inception of weird fiction? Why did British weird authors receive greater literary recognition than their American counterparts? Why since the 1980s are we experiencing a resurgence of weird fiction through the New Weird movement, and how do these authors continue the themes of their predecessors into the 21st century? Readings for this class will span from early authors who had a strong influence over later weird writers (like E.T.A. Hoffman and Robert Chambers) to the weird writers of the early 20th century (like Lovecraft, Robert Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, Lord Dunsany, and Algernon Blackwood) to New Weird authors (including China Miéville, Thomas Ligotti, and Laird Barron). -

Disciples of the Outer Gods Homebrewed Cthulhu Mythos Themed Options for Dnd 5Th Edition

Disciples of the Outer Gods Homebrewed Cthulhu Mythos Themed Options for DnD 5th Edition While not everybody worshiping or studying these eldritch Foreword entities is a raving cultist, long-term exposure to unearthly The purpose of this document is to provide alternative powers and being in contact with even the unconscious mind character building options themed around H.P Lovecraft's of such utterly alien beings is not something a mortal mind is Cthulhu Mythos. It originally started as a list of alternative built to handle, eventually rendering the person insane by warlock patrons based on Lovecraft's Outer Gods, but after conventional standards, although in truth it is perhaps more some positive feedback I decided to expand the scope to accurate to say that they have merely come to see the cover other classes as well, giving them specialization related universe from a very different point of view, one that might to serving or fighting eldritch horrors. actually be closer to the true nature of existence. Now, I know the traditional Lovecraftian horror isn't very compatible with a game like DnD, as one of the major themes of Lovecraft's stories was the insignificance and New Warlock Patrons: The powerlessness of humans, which goes out of the window Outer Gods when the player characters are all powerful heroes. However, The PHB already has the Great Old One patron, which is even during Lovecraft's own times the Mythos was used as a your generic Lovecraftian horror as a warlock patron, but I backdrop for multiple kinds of stories: Lovecraft's own wanted to create ones based on particular well-known deities “Dreamland” stories could be adapted to a fantasy game of Lovecraft's mythos. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} in a Lonely Place by Karl Edward Wagner in a Lonely Place by Karl Edward Wagner

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} In a Lonely Place by Karl Edward Wagner In a Lonely Place by Karl Edward Wagner. In a Lonely Place by Karl Edward Wagner (Collected 1983): This mid-1980’s collection of short stories and novellas by Wagner includes probably his most famous story, the award-winning “Sticks” from the mid-1970’s. Wagner, who died too young in 1995, was a major writer, publisher and anthologist in the horror, dark-fantasy, and sword-and-sorcery genres for more than 20 years, with his annual Year’s Best Horror anthology from DAW pretty much setting the gold standard for genre ‘Best of’ collections from the early 1980’s until Wagner’s death and resultant cancellation of the series. Here, we get many of his best horror stories, including the forementioned “Sticks”, a whopper of a Lovecraft homage that also references the artwork and lifestory of pulp illustrator Lee Brown Coye. Did the makers of The Blair Witch Project read “Sticks” at some point? If not, it’s an incredible coincidence. Other stories bounce off Lovecraft, Manly Wade Wellman and Robert Chambers’ seminal The King in Yellow in interesting and productive ways, all without requiring any actual knowledge of the references for readerly enjoyment. The novella “Beyond Any Measure” remains, nearly thirty years after its first appearance, one of the five or six cleverest vampire stories ever written. Highly recommended . Lonely Place by Karl Edward Wagner. Connecting readers with great books since 1972. Used books may not include companion materials, some shelf wear, may contain highlighting/notes, may not include cdrom or access codes. -

Eldritch Horrors: the Modernist Liminality of H.P

ELDRITCH HORRORS: THE MODERNIST LIMINALITY OF H.P. LOVECRAFT’S WEIRD FICTION DALE ALLEN CROWLEY Bachelor of Arts in English Baldwin-Wallace University December 2014 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH at CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May 2017 THIS THESIS IS HEREBY APPROVED FOR Dale Allen Crowley candidate for the Master of Arts in English degree for the Department of English & CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY’S College of Graduate Studies by ____________________________________________________ ~ ~ ~ Dr. James Marino _______________________________________ ~ department & date ____________________________________________________ ~ ~ ~ Dr. Adam Sonstegard _______________________________________ ~ department & date ____________________________________________________ ~ ~ ~ Dr. Julie Burrell _______________________________________ ~ department & date 9 May 2017 Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank the members of my thesis committee – Dr. James Marino, Dr. Adam Sonstegard, and Dr. Julie Burrell – for their help in bringing this project to fruition. I’d also like to acknowledge their patience and understanding with regards to my fascination with a very small subsect of genre fiction. Through them, I gained a deeper understanding of early twentieth century literature and I am thoroughly grateful for it. I would especially like to thank Dr. James Marino for his always insightful critical thought, his frequent challenging of my arguments, and his erudite and often witty observations of H.P. Lovecraft and New England. I would also like to express my deep love, gratitude, and appreciation for my wife, Michelle, and my children – Connor, and Meghann – who tolerated many long nights and weekends without me as I attended class, studied, and obsessed over H.P. Lovecraft in pursuit of my graduate degree. I could not have done this without you. -

A Structuralist Approach to Understanding the Fiction of HP Lovecraft

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 1992 Out of the Shadows: A Structuralist Approach to Understanding the Fiction of H. P. Lovecraft James A. Anderson University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Anderson, James A., "Out of the Shadows: A Structuralist Approach to Understanding the Fiction of H. P. Lovecraft" (1992). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 696. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/696 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OUT OF THE SHADOWS: A STRUCTURALIST APPROACH TO UNDERSTANDING THE FICTION OF H.P. LOVECRAFT BY JAMES A. ANDERSON A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 1992 Abstract Although Howard Phillips Lovecraft (1890-1937) is generally regarded as one of the world's finest writers of horror and science fiction, his work has received little critical attention by mainstream critics. This study takes Lovecraft out of the shadows of literature by shedding light upon his work through a structural analysis of fifteen of his stories. This analysis shows that Lovecraft's fiction, while it may appear fantastic, expresses early twentieth century naturalism in a cosmic context. Part One subjects four of Lovecraft's best known stories to a detailed structural analysis using the theories of Roland Barthes and Gerard Genette to isolate Lovecraft's major themes and narrative techniques.