Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HERALD Issue See Insert the Only English-Jewish Weekly in Rhode Island and Southeastern Massachusetts

+uuu-H,t-ll-H·H·4H,4H·tr•5-DIGIT 02906 2239 11 /30/93 H bl R. I. JEWISH HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 130 SESSIONS ST. ,.. t PROVIDEN CE, Rl _____0290b h Rhode I'---- ...... Special Passover --HERALD Issue See Insert The Only English-Jewish Weekly in Rhode Island and Southeastern Massachusetts VOLUME LXXVIV, NUMBER 19 NISAN 10, 5753 / THURSDAY, APRIL 1, 1993 35t PER COPY Knesset Elects Ezer Weizman Celia Zuckerberg, Longtime Herald as Israel's Seventh President Editor, Dies at 74 by Cynthia Mann come under intense criticism by Anne S. Davidson JERUSALEM (JT A) - The for its inability to curb an unre Heuld Editor election last week of Ezer lenting wave of Arab violence. 4 Weizman to be Israel's seventh Al though Weizman was Celia G. Zuckerberg, 74 , a president is being seen here as favored to win, tension was in longtime editor of the RhoJ1• /s la11d Jrwis/i Herald , died March a much-needed victory for the (Continued on Page 6) beleaguered Labor Party. 27 at Miriam Hospital after a Weizman, 68, a national war brief illness. A resident of 506 hero and former defense min Morris Ave., Providence, she ister known for his outspoken Jewish Settler worked for the He rald from the individualism, was elected by late 1950s to the late 1970s, the Knesset on March 24 in a Kills an Arab holding the title of managing t'" 66-53 vote with one absten by Cynthia Mann editor for about 20 years. tion. JERUSA LEM UTA)-AJew But his victory over Ukud ish settler shot and killed a 20- "She was like a one-man Knesset member Dov Shi\ year-old Palestinian whose feet editor. -

Sessions at a Glance

SESSIONS AT A GLANCE WEEK ONE Morning Seminars CLICK A BLUE SCIENCE/COOKING Science of Food HEADER TO JUMP THEATER Fun and Magic of Mime TO THAT SECTION OF YOUR GUIDE LIFESKILLS An Introduction to Fullforce Self Defense MATH The Mathematics of Tilings JOURNALISM Journalism: Reporting, Writing, and Publishing the News THEATER Dialects for Stage and Film ART/SCIENCE Making a Dinosaur POSITIVE PSYCHOLOGY Happiness 101: Positive Psychology ART The Art of Making Art: An Introduction to Process Art FILM/TECHNOLOGY Filmmaking and Visual Effects BUSINESS So You Want to be a VC FIELD SCIENCE/HISTORY Hannibal: Interactive Field Science, Maps, and GIS HISTORY/FASHION Image and Fashion: The Bizarre History LANGUAGE Foreign Language: Intro to Russian LAW/SOCIAL STUDIES American Criminal Law: With Case Studies and Visuals MUSIC Beginning Guitar SCIENCE/WRITING Modern Science Communication MATH Creative Math: How Does UPS Get Your Package to its Destination on Time WEEK ONE Afternoon Seminars ART Rangoli Art BUSINESS The Language of Leadership DANCE Hip-Hop Dance & Choreography Intersession Guide 2018 SESSIONS AT A GLANCE WEEK ONE Afternoon Seminars Continued CLICK A BLUE MATH How Big is Big: An Exploration of Infinity HEADER TO JUMP WRITING Nonfiction Writing: The Art of Crafting True Stories TO THAT SECTION OF YOUR GUIDE ART/SCIENCE Making a Dinosaur ART/COOKING Cake Decorating FILM/WRITING Screenwriting SCIENCE Forensic Science MUSIC/TECHNOLOGY Electronic Music Production HISTORY/LITERATURE Hannibal in Roman Literature, Hands-On Literary Sleuthing -

January 26-28, 2018

2 January 26-28, 2018 ramahdarom.org Exceptional experiences in Jewish living and learning all year long. Welcome! Thank you for joining Ramah Darom for our second annual Farm 2 Table Tu B’Shevat. We are so excited about the retreat, and hope that you have an amazing experience! This weekend we will come together to celebrate Tu B’Shevat, the Jewish festival of trees, with delicious, organic, locally-sourced meals prepared by our stellar Ramah Darom Executive Chef Todd Jones, in partnership with Souper Jenny, our farm to table guest chef. Throughout the weekend you will have the opportunity to experience ways YOU can make a difference through inspiring learning sessions with Rabbi Justin Goldstein, Jeffrey Cohan, and Naftali & Anna Hanau. You will have the opportunity to spend time with the farm animals of Ivy Rose Farms, learn about urban farm- ing and get your hands dirty planting with Jonathan Tescher, Robby Astrove, and Laura Labovitz. And while you are connecting to the Earth and your Jewish roots, we will all have a chance to connect to one another, as we grow and build this special community through Shabbat and the weekend. If you have any questions throughout the weekend, please do not hesitate to fine one of our amazing Ramah Darom Staff—we are always happy to help! Looking forward to a beautiful weekend together, Eliana Leader and the Ramah Darom Retreat Center Team 2 Daily Schedule FRIDAY: JANUARY 26 TIME ACTIVITY LOCATION 3:00 pm - Registration Welcome 5:00 pm Center 4:00 pm - Pita Making for Shabbat Pizza Oven 5:30 pm 4:00 -

A Reading of Porphyry's on Abstinence From

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Justice Purity Piety: A Reading of Porphyry’s On Abstinence from Ensouled Beings A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Classics by Alexander Press 2020 © Copyright by Alexander Press 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Justice Purity Piety: A Reading of Porphyry’s On Abstinence from Ensouled Beings by Alexander Press Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Los Angeles, 2020 Professor David Blank, Chair Abstract: Presenting a range of arguments against meat-eating, many strikingly familiar, Porphyry’s On Abstinence from Ensouled Beings (Greek Περὶ ἀποχῆς ἐµψύχων, Latin De abstinentia ab esu animalium) offers a sweeping view of the ancient debate concerning animals and their treatment. At the same time, because of its advocacy of an asceticism informed by its author’s Neoplatonism, Abstinence is often taken to be concerned primarily with the health of the human soul. By approaching Abstinence as a work of moral suasion and a work of literature, whose intra- and intertextual resonances yield something more than a collection of propositions or an invitation to Quellenforschung, I aim to push beyond interpretations that bracket the arguments regarding animals as merely dialectical; cast the text’s other-directed principle of justice as wholly ii subordinated to a self-directed principle of purity; or accept as decisive Porphyry’s exclusion of craftsmen, athletes, soldiers, sailors, and orators from his call to vegetarianism. -

Shanlax International Journal of Arts, Science and Humanities

Shanlax International Journal of Arts, Science and Humanities (A PEER-Reviewed-Refereed/Scholarly Quarterly Journal with Impact Factor) Vol. 5 Special Issue 2 September, 2017 Impact Factor: 3.025 ISSN: 2321 – 788X UGC approved Journal No: 43960 National Seminar on GENDER AND LAW: A CHALLENGE TO SAFE WORLD ORDER 20 & 21 September 2017 Organized By RC: 10 Gender Studies - Indian Sociological Society (ISS) And Department of Sociology Volume – 2 Special Issue Editor Dr.C.Hilda Devi Professor Department of Sociology Mother Teresa Women's University MOTHER TERESA WOMEN’S UNIVERSITY Kodaikanal PREFACE GENDER AND LAW: A CHALLENGE TO SAFE WORLD ORDER Law and Gender equality, maps the issue of Gender and Law reforms upon a canvas of History and Politics, and explores strategies which could safeguard women’s rights within India’s fear of complex social and political boundaries. Law is pervasive and affects many aspects of people’s lives, women and men alike. Law and justice impact people’s capacity to accumulate endowments, enjoy returns to such endowments, access rights and resources, and act as free, autonomous agents in society. The World Development Report (WDR) 2012 on Gender Equality and Development highlights the relevant role of law and justice in achieving gender equality. Teaching about gender is increasingly looked as a way to make progress in a global culture that continues to uphold men and boys' entitlement to control women and girls. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, ratified by the UK in April 1986, is an international bill of rights for women which recognizes the role of culture and tradition in perpetuating gender discrimination. -

Animal-Industrial Complex‟ – a Concept & Method for Critical Animal Studies? Richard Twine

ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 1 2012 Journal for Critical Animal Studies ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 1 2012 EDITORAL BOARD Dr. Richard J White Chief Editor [email protected] Dr. Nicole Pallotta Associate Editor [email protected] Dr. Lindgren Johnson Associate Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Laura Shields Associate Editor [email protected] Dr. Susan Thomas Associate Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Richard Twine Book Review Editor [email protected] Vasile Stanescu Book Review Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Carol Glasser Film Review Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Adam Weitzenfeld Film Review Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Matthew Cole Web Manager [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD For a complete list of the members of the Editorial Advisory Board please see the Journal for Critical Animal Studies website: http://journal.hamline.edu/index.php/jcas/index 1 Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume 10, Issue 1, 2012 (ISSN1948-352X) JCAS Volume 10, Issue 1, 2012 EDITORAL BOARD .............................................................................................................. -

1 Rabbi Challenges Synagogues to Go Vegan

The pictured: rabbi dr. shmuly yanklowitz rabbi challenges synagogues since 1966 No. 202 to go vegan, page 4 autumn 2017 elul 5777 ‘They shall not hurt nor destroy 1 on all my holy mountain’ (Isaiah) on the renovation of our building, which Welcome to will become Europe’s first Jewish centre dedicated to ethical eating. the jewish From all of us at JVS, we wish you Shana Tovah U’Metukah, a very happy vegetarian new year and sweet New Year. ith Rosh Hashana, the Jewish new year,just around Lara Smallman the corner, we’ve got a very Director, Jewish Vegetarian Society Wspecial cookery corner, packed full of sweet recipes. Find more inspiration on our website jvs.org.uk/ recipes. An increasing number of kosher bakeries offer water challot, which contain no eggs or milk. If you are keen to make your own, we recommend JVS member Jemma Jacobs’ recipe, see the back page. In this issue we meet the inspirational Rabbi who is inviting synagogues to try veganism, see page 4 for the full story. We get a behind the scenes look at what happened on Birthright’s first ever vegan trip over on page 26. Read about the British politicians and the vegan synagogue celebrities who are joining forces to call for challenge, p4 an end to foie gras - a product of immense of cruelty - the liver of a duck or goose fattened by force-feeding corn with a feeding tube, page 6. We are delighted to once again be working with Limmud Conference, newly renamed Limmud Festival, which attracts over 2,500 people to the week-long winter event. -

Wildlife Rights and Human Obligations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Central Archive at the University of Reading Wildlife Rights and Human Obligations A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy Julius Kapembwa June 2017 DECLARATION I confirm that this is my own work and the use of materials from other sources has been properly and fully acknowledged. Julius Kapembwa __________________ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A look back at early drafts of some chapters in this thesis reminds me how easy it is to underestimate my debt to Brad Hooker and Elaine Beadle—my supervisors—for the state of the finished thesis. With their intellectual guidance and moral support, which sometimes extended beyond my research, my supervisors helped me settle with relative ease into my research. My supervisors will surely be my models for fairness, firmness, and professionalism in any supervision work I will undertake in the future. I was fortunate to have presented my thesis work-in-progress on five occasions in the Department of Philosophy’s vibrant weekly Graduate Research Seminar (GRS). I would like to thank all graduate students for their engagement and critical feedback to my presentations. Special thanks to David Oderberg, who directed the GRS programme and offered important feedback during the sessions. I am thankful to Julia Mosquera, Joseph Connelly, and Matteo Benocci, who were enthusiastic respondents to my presentations. Thank you to George Mason, who kindly read and gave me some written feedback on parts of Chapter 5. This thesis has resulted in, and benefited from, four conference presentations. -

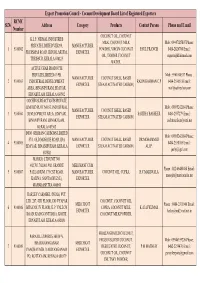

Exporters List

Export Promotion Council - Coconut Development Board List of Registered Exporters RCMC Sl.No Address Category Products Contact Person Phone and E mail Number COCONUT OIL, COCONUT K.L.F. NIRMAL INDUSTRIES MILK, COCONUT MILK Mob : 09447025807 Phone : PRIVATE LIMITED VIII/295, MANUFACTURER 1 9100002 POWDER, VIRGIN COCONUT PAUL FRANCIS 0480-2826704 Email : FR.DISMAS ROAD, IRINJALAKUDA, EXPORTER OIL, TENDER COCONUT [email protected] THRISSUR, KERALA 680125 WATER, ACTIVE CHAR PRODUCTS PRIVATE LIMITED 63/9B, Mob : 9961000337 Phone : MANUFACTURER COCONUT SHELL BASED 2 9100003 INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT RAZIN RAHMAN C.P 0484-2556518 Email : EXPORTER STEAM ACTIVATED CARBON, AREA, BINANIPURAM, EDAYAR, [email protected] ERNAKULAM, KERALA 683502 COCHIN SURFACTANTS PRIVATE LIMITED PLOT NO.63, INDUSTRIAL Mob : 09895242184 Phone : MANUFACTURER COCONUT SHELL BASED 3 9100004 DEVELOPMENT AREA, EDAYAR, SAJITHA BASHEER 0484-2557279 Email : EXPORTER STEAM ACTIVATED CARBON, BINANIPURAM, ERNAKULAM, [email protected] KERALA 683502 INDO GERMAN CARBONS LIMITED Mob : 09895242184 Phone : 57/3, OLD MOSQUE ROAD, IDA MANUFACTURER COCONUT SHELL BASED DR.MOHAMMED 4 9100005 0484-2558105 Email : EDAYAR, BINANIPURAM, KERALA EXPORTER STEAM ACTIVATED CARBON, ALI.P. [email protected] 683502 MARICO LTD UNIT NO. 402,701,702,801,902, GRANDE MERCHANT CUM Phone : 022-66480480 Email : 5 9100007 PALLADIUM, 175 CST ROAD, MANUFACTURER COCONUT OIL, COPRA, H.C MARIWALA [email protected] KALINA, SANTACRUZ (E), EXPORTER MAHARASHTRA 400098 HARLEY CARMBEL (INDIA) PVT. LTD. 287, -

Now We're Opening the UK's 1St Jewish

JVS has ... been now promoting we’re aopening kinder society the without UK’s killing 1st animals Jewish for foodcentre since for1966 vegetarianism & environment How you can make it happen: back page since 1966 no. 197 summer 2016 iyyar 5776 ‘They shall not hurt nor destroy on all my holy mountain’ (Isaiah) 1 U.S. has opened in Philadelphia. Welcome to the In this issue, we profile Fania Lewando, a woman ahead of her time, summer 2016 cooking vegetarian food in 1930s issue of the Jewish Lithuania. Over on page 12, you can find out about how Animal Equality Vegetarian is using virtual reality to revolutionise animal rights campaigning. e are seeking donations I hope you enjoy reading our from members and magazine. The next issue will be a supporters towards the special one celebrating 50 years of the transformation of the Jewish Vegetarian Quarterly. I wish all Wground floor of our Golders Green HQ into of our readers a lovely summer. We look an open-plan, multi-purpose community forward to welcoming you to our new centre, with a professional kitchen for centre when it opens the autumn. cookery classes, a growing garden and space to house two like-minded charities. Turn to the back page to find out more Lara Smallman about our plans and how you can help. Director, Jewish Vegetarian Society There have been some fantastic developments around the world: • New Zealand now recognises all animals as sentient beings. • Sales of processed meat in Israel have plumetted following the World Health Organization’s decision to classify it as a carcinogen in late 2015. -

Westport Eastbayri.Com THURSDAY, JULY 24, 2014 VOL

ShorelinesShorelinesWestport eastbayri.com THURSDAY, JULY 24, 2014 VOL. 20, NO. 30 $.75 Firm to study Westport kicks up its heels handicapped access options at Beach Avenue BY BRUCE BURDETT [email protected] It was talk of providing a more accessible beach for people with disabilities that led to the year- long debate over Beach Avenue and last week the Board of Select- men voted to launch a study of how such a beach might be set up. The board voted to pay CLE Engineering $13,900 to conduct a preliminary feasibility study, assessment and design of a way to help those with handicaps get easily from Beach Avenue across the dunes to the beach. Although no firm plan has been developed, there has been talk at past meetings of building one or more short boardwalks to the beach. Not yet addressed is how such a beach might be staffed. The idea of opening a more accessible beach surfaced came PHOTOS BY RICHARD W. DIONNE JR. in response to concerns that the town's other beaches, including Cherry & Webb, involve a long After the rain, walk on a cross-dunes path from fair fun returns the parking lot that is difficult or impossible for some people, ABOVE: Tara Reed and her husband Mark including senior citizens. rip into a 10-inch timber during the Jack Along Beach Avenue, however, and Jill crosscut saw competition on Satur- the beach is much closer to the day at the Westport Fair held every summer road. at the Pine Hill Road fairgrounds. RIGHT: That discussion led to often Olivia Purdy, 4, of Portsmouth, pets an heated debate over the question award winning heifer. -

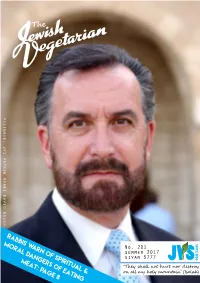

JVS Mag No.201 – June 2017

The pictured: jvs patron rabbi david rosen rabbis warn of spiritual & moral dangers of eating since 1966 No. 201 summer 2017 sivan 5777 meat: page 8 ‘They shall not hurt nor destroy 1 on all my holy mountain’ (Isaiah) which you can read about on page 4. Welcome to See page 6 for details of upcoming events. As always, we love hearing from the jewish you. Please do get in touch with us via [email protected] with ideas you have for vegetarian this magazine, and for our events. hat a busy few months it has been! In May we hosted Lara Smallman our 52nd Annual General Director, Jewish Vegetarian Society WMeeting. A big thank you to Ori Shavit, who joined us live from Israel via Skype to talk about her role in building the vegan movement as well as the many fantastic developments in Israel, see vegansontop.co.il to find out more about Ori. We were also joined by Gavin Fernback who spoke about his personal journey to veganism, and how he veganised his London café The Fields Beneath, which you can read all about on page 13 We were delighted to secure a double page spread in the Jewish Chronicle newspaper during National Vegetarian Week, in which I shared my top tips for going veggie, see campaigning reaches page 10 for more. new heights, p26 Recently the JVS Board met Jeffrey Cohan, Director of Jewish Veg in the US, who is a regular contributor to this magazine. We look forward to collaborating with Jewish Veg in the future on joint projects - watch this space.