Pocketing Caspian Black Gold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 12 May 2006 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Hemming, J. (1998) 'The implications of the revival of the oil industry in Azerbaijan.', Working Paper. University of Durham, Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, Durham. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.dur.ac.uk/sgia/ Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk University of Durham Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies *********************************** THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE REVIVAL OF THE OIL INDUSTRY IN AZERBAIJAN *********************************** by Jonathan Hemming CMEIS Occasional Paper No. 58 June 1998 CMEIS Occasional Papers ISSN 1357-7522 No. 58 CMEIS Occasional Papers are published by: Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies University of Durham South End House South Road Durham DH1 3TG United Kingdom Tel: 0191-374 2822 Fax: 0191-374 2830 Editorial board: Professor Timothy Niblock Dr Anoushiravan Ehteshami Dr Paul Starkey Dr Fadia Faqir Series editor: Dr Neil Quilliam The Occasional Papers series covers all aspects of the economy, politics, social science, history, literature and languages of the Middle East. -

Azerbaijan Investment Guide 2015

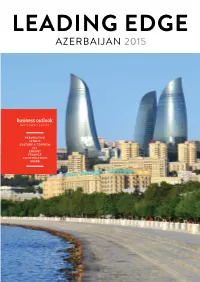

PERSPECTIVE SPORTS CULTURE & TOURISM ICT ENERGY FINANCE CONSTRUCTION GUIDE Contents 4 24 92 HE Ilham Aliyev Sports Energy HE Ilham Aliyev, President Find out how Azerbaijan is The Caspian powerhouse is of Azerbaijan talks about the entering the world of global entering stage two of its oil future for Azerbaijan’s econ- sporting events to improve and gas development plans, omy, its sporting develop- its international image, and with eyes firmly on the ment and cultural tolerance. boost tourism. European market. 8 50 120 Perspective Culture & Finance Tourism What is modern Azerbaijan? Diversifying the sector MICE tourism, economic Discover Azerbaijan’s is key for the country’s diversification, international hospitality, art, music, and development, see how relations and building for tolerance for other cultures PASHA Holdings are at the future. both in the capital Baku the forefront of this move. and beyond. 128 76 Construction ICT Building the monuments Rapid development of the that will come to define sector will see Azerbaijan Azerbaijan’s past, present and future in all its glory. ASSOCIATE PUBLISHERS: become one of the regional Nicole HOWARTH, leaders in this vital area of JOHN Maratheftis the economy. EDITOR: 138 BENJAMIN HEWISON Guide ART DIRECTOR: JESSICA DORIA All you need to know about Baku and beyond in one PROJECT DIRECTOR: PHIL SMITH place. Venture forth and explore the ‘Land of Fire’. PROJECT COORDINATOR: ANNA KOERNER CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: MARK Elliott, CARMEN Valache, NIGAR Orujova COVER IMAGE: © RAMIL ALIYEV / shutterstock.com 2nd floor, Berkeley Square House London W1J 6BD, United Kingdom In partnership with T: +44207 887 6105 E: [email protected] LEADING EDGE AZERBAIJAN 2015 5 Interview between Leading Edge and His Excellency Ilham Aliyev, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan LE: Your Excellency, in October 2013 you received strong reserves that amount to over US $53 billion, which is a very support from the people of Azerbaijan and were re-elect- favourable figure when compared to the rest of the world. -

Companies Involved in Oilfield Services from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Companies Involved in Oilfield Services From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Diversified Oilfield Services Companies These companies deal in a wide range of oilfield services, allowing them access to markets ranging from seismic imaging to deep water oil exploration. Schlumberger Halliburton Baker Weatherford International Oilfield Equipment Companies These companies build rigs and supply hardware for rig upgrades and oilfield operations. Yantai Jereh Petroleum Equipment&Technologies Co., Ltd. National-Oilwell Varco FMC Technologies Cameron Corporation Weir SPM Oil & Gas Zhongman Petroleum & Natural Gas Corpration LappinTech LLC Dresser-Rand Group Inc. Oilfield Services Disposal Companies These companies provide saltwater disposal and transportation services for Oil & Gas.. Frontier Oilfield Services Inc. (FOSI) Oil Exploration and Production Services Contractors These companies deal in seismic imaging technology for oil and gas exploration. ION Geophysical Corporation CGG Veritas Brigham Exploration Company OYO Geospace These firms contract drilling rigs to oil and gas companies for both exploration and production. Transocean Diamond Offshore Drilling Noble Hercules Offshore Parker Drilling Company Pride International ENSCO International Atwood Oceanics Union Drilling Nabors Industries Grey Wolf Pioneer Drilling Co Patterson-UTI Energy Helmerich & Payne Rowan Companies Oil and Gas Pipeline Companies These companies build onshore pipelines to transport oil and gas between cities, states, and countries. -

Multi0page.Pdf

'-4 -. _ ,',-r p4 -. F . - e ; Pt , :L; . *.' . 1H, _= _ - ~~~~~~~~~. c _. .4 . 4 4 ,'_,,*,,,t, 3ta<eniC:-p>S .- c .~ -:;43 .-*- _|~~~~ i V4> f -~ .4' ~ "OR1 ;RL DN B-A N-K5,' CD'l S,C'"jSr I O P A P F. R . N0 O A42 6 3 _. f~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~-' * M j £ *x~~~~~~~~~" , '--. 1-'-' t ~~~~~~WDP426 94 *..- 4 <. s = _ ~~~~~~~~~~~~April 2002 Public Disclosure Authorized l~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~4f .7'R - ..~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~ ~4 ~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 4 ~ ~ ~ ~I U ,_ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ .4 . A- - .. .feN .n~ ~ ~~ ,_> ~ ~ ~ ~ Public Disclosure Authorized 1A~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~1 Public Disclosure Authorized 5 .,- 4-s~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~1 A Ga Public Disclosure Authorized -- .- .A - W :4_ ., ~~~~~. ? * ., o ~~~~ ; is~~~~~~~~-' :_ ., , _ _ '4 ,* 4, - * Recent World Bank Discussion Papers No 351 From Universal Food Subsidies to a Self-Targeted Program A Case Study in Tunisian Reform Laura Tuck and Kathy Lindert No. 352 China's Urban Transport Development Strategy. Proceedings of a Symposium in1 Beijing, November 8-10, 1995. Edited by Stephen Stares and Liu Zhi No. 353 Telecommunications Policiesfor Sub-Saharan Africa. Mohammad A. Mustafa, Bruce Laidlaw, and Mark Brand No. 354 Saving across the World Puzzles and Policies Klaus Schmidt-Hebbel and Luis Serv6n No. 355 AgriculIture and Gernian Reunification. Ulrich E. Koester and Karen M. Brooks No. 356 Evaluating Health Projects Lessonsfrom the Literature. Susan Stout, Alison Evans, Janet Nassim, and Laura Raney, with substantial contributions from Rudolpho Bulatao, Varun Gauri, and Timothy Johnston No. 357 Innovations and Risk Taking The Engine of Reform in Local Government in Latin America and the Caribbean.Tim Campbell No. 358 China's Non-Bank Financial Institutions:Trustand Investment Companies. -

SN3.3.BTC Pipeline.Lessons Learned from ESIA. Pollett, Miller And

BTC Oil Pipeline-Caspian to Mediterranean Seas. Lessons Learned from the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment and Mitigation Process. By Ted Pollett, Patty Miller and Shawn Miller IAIA Conference-Vancouver April 2004 BTC Pipeline Route Pipeline Characteristics » 1760 km in length (Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey) » Capacity: 50 million tonnes crude oil per annum » Avoids Turkish Straits (Bosphorus) » Passes through a wide variety of agro-ecological areas, landforms and land use types Traverses wide variety of land types Background » Pipeline will provide first direct transportation link between hydrocarbon rich, land locked Caspian Sea and Mediterranean » New source of crude oil for global markets » Will enhance Turkey’s strategic significance-hub for energy distribution through Mediterranean » Will establish ‘east-west energy corridor’-already strengthened relations between Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey Project Costs and Funding » Total project Costs: US$3.6 billion (including terminals and associated facilities). » US$ 1 billion from shareholders » US$ 2.6 billion credit by lenders-including IFC and EBRD, export credit agencies (Europe, US and Japan), commercial banks & political risk insurers Facts about IFC » Private sector arm of the World Bank Group » Owned by 176 member countries » Emerging markets focus » Provide loans & equity, advisory services and mobilization of capital » FY03 commitments: $5.03 billion » Total IFC portfolio: $16.78 billion IFC’s Mission We promote sustainable private sector investment in developing countries, -

Slussac WP Garnet SOCAR

The State as a (Oil) Company? The Political Economy of Azerbaijan∗ Samuel Lussac, Sciences Po Bordeaux GARNET Working Paper No. 74/10 February 2010 Abstract In 1993, Azerbaijan was a country at war, suffering heavy human and economic losses. It was then the very example of a failing country in the post-soviet in the aftermath of the collapse of the USSR. More than 15 years after, it is one of the main energy partners of the European Union and is a leading actor in the Eurasian oil sector. How did such a change happen? How can Azerbaijan have become so important in the South Caucasian region in such a short notice? This paper will focus on the Azerbaijani oil transportation network. It will investigate how the Azerbaijani oil company SOCAR and the Azerbaijani presidency are progressively taking over this network, perceived as the main tool of the foreign policy of Azerbaijan. Dealing with the inner dynamics of the network, this paper will highlight the role of clanic and crony capitalist structures in the makings of a foreign policy and in the diversification of an emerging oil company. Keywords: Azerbaijan, Network, Oil, South Caucasus, SOCAR. Address for correspondence: 42 rue Daguerre 75014 Paris Email: [email protected] ∗ The author is grateful to Helge Hveem and Dag Harald Claes for their valuable comments on previous versions of this research. This study has mainly been written during a research fellowship at the University of Oslo thanks to the generous support of GARNET (FP 6 Network of Excellence Contract n°513330). 1 Introduction Since 1991, Azerbaijan has drawn the energy sector’s attention, first for its oil reserves and now for its gas ones. -

The Outlook for Azerbaijani Gas Supplies to Europe: Challenges and Perspectives

June 2015 The Outlook for Azerbaijani Gas Supplies to Europe: Challenges and Perspectives OIES PAPER: NG 97 Gulmira Rzayeva OIES Research Associate The contents of this paper are the authors’ sole responsibility. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies or any of its members. Copyright © 2015 Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (Registered Charity, No. 286084) This publication may be reproduced in part for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. ISBN 978-1-78467-028-3 i April 2015: The Outlook for Azerbaijani Gas Supplies to Europe Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. vi Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Natural Gas in Azerbaijan – Historical Context .......................................................................... 4 The first stage of Azerbaijan’s oil and gas history (1846-1920)...................................................... -

SOCAR’S STRATEGY ACG, Shah Deniz and Beyond… April, 2017

SOCAR’S STRATEGY ACG, Shah Deniz and beyond… April, 2017 VITALIY BAYLARBAYOV, Deputy Vice-President for Investments and Marketing Famous Azerbaijan Oil Firsts… Azerbaijan A central hydrocarbon producing region since beginning of oil production age. In late 19th century the country produced half of the world’s consumption of oil. Azerbaijan’s oil production during World War II was crucial to the victory of the Soviet Union over Nazi Germany. SOCAR Founded during the Soviet period under various different names. In September 1992, SOCAR was established by the independent Republic of Azerbaijan. Our vision is to become a vertically integrated international energy company based on advanced experience in operation efficiency, social and environmental responsibility. Famous Azerbaijan Oil Firsts… • First oil well in the world was drilled in 1848 in Baku in Bibi Heybat oil field • In 1900 Azerbaijan produced more than 50% of world’s oil = 11.4 million tons • In 1897-1907 the 1st largest oil pipeline in the world was built from Baku to Batumi (883 km x 200mm) • First oil tanker Zoroaster by Branobel Company owned by Ludvig and Robert Nobel was built in 1885 and delivered to the Caspian Sea • About 80% of oil used during WW II by the USSR was produced in Baku (peak production – 23.5 million tons in 1941) • First offshore oil production in the world started in Azerbaijan (1924 – Bibi Heybat seaside, 1949 – Oily Rocks – in open sea) Company Strategic Goals Maintain position as the leading oil and gas company in Azerbaijan and a key regional player, and become an international oil and gas group with vertically-integrated upstream, midstream and downstream operations. -

Azeri, Chirag, Gunashli Full Field Development Produced Water Disposal Project (ACG FFD PWD)

Azeri, Chirag, Gunashli Full Field Development Produced Water Disposal Project (ACG FFD PWD) Operated by Environmental and Socio-economic Impact Assessment Final Report January 2007 ACG FFD PWD Project ESIA Final Report This page is intentionally blank. January 2007 ACG FFD PWD Project ESIA Final Report Master Table of Contents Glossary................................................................................................................................... i Units and Abbreviations ................................................................................................. xxii References ...................................................................................................................... xxviii Executive Summary ES1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................i ES1.1 Project background and objective .....................................................................i ES2 ESIA process................................................................................................................iii ES3 Project Description.........................................................................................................v ES3.1 Option assessment...........................................................................................v ES3.2 Selected project option....................................................................................vi ES3.3 ACG FFD PWD Project procurement and transportation............................. -

APPENDIX 2A Azeri Chirag Gunashli Production Sharing Agreement

APPENDIX 2A Azeri Chirag Gunashli Production Sharing Agreement Extract Azeri Central East Project Appendix 2A Environmental & Social Impact Assessment ARTICLE 26 - Environmental Protection and Safety 26.1 Conduct of Operations Contractor shall conduct the Petroleum Operations in a diligent, safe and efficient manner in accordance with Good International Petroleum Industry Practice and shall take all reasonable actions in accordance with said standards to minimise any potential disturbance to the general environment, including the surface, subsurface, sea, air, lakes, rivers, animal life, plant life, crops, other natural resources and property. The order of priority for actions shall be the protection of life, environment and property. 26.2 Emergencies In the event of emergency and accidents, including explosions, blow-outs, leaks and other incidents which damage or might damage the environment, Contractor shall promptly notify SOCAR and MENR of such circumstances and of its first steps to remedy this situation and the results of said efforts. Contractor shall use all reasonable endeavours to take immediate steps to bring the emergency situation under control and protect against loss of life and loss of or damage to property and prevent harm to natural resources and to the general environment. Contractor shall also report to SOCAR and appropriate Government authorities on the measures taken 26.3 Compliance Contractor shall comply with present and future Azerbaijani laws or regulations of general applicability with respect to public health, safety and protection and restoration of the environment, to the extent that such laws and regulations are no more stringent than the then current Good International Petroleum Industry Practice being at the date of execution of this Contract those shown in Appendix 9, with which Contractor shall comply. -

Oil and Networks in Azerbaijan*

한국지역지리학회지 제11 권 제 6 호 (2005) 640-656 Black Gold or the Devil’s Curse? Oil and Networks in Azerbaijan* Chaimun Lee** 검은 황금인가 악마의 저주인가? 아제르바이쟌의 석유와 연줄망 * 이 채 문** Abstract :A chronic depression in the Korean economy, which depends mostly on imported oil, has been attributed partly to rising crude oil prices recently. Against the backdrop of these realities in Korea, Azerbaijan in the Caspian region, with vast oil and gas deposits, has been greeted enviously by some Koreans. Many transition economies, especially on the Caspian region trumpeted by the oil boom, however, are rich in natural resources, but the benefits of those resources are appropriated by the local elite in collusion with foreign companies. Azerbaijan, in particular, is dominated by a series of internal and external patronage networks. Foreign capital nourishes those networks surrounding President Aliev. Thus, the case of Azerbaijan shows that resource rents in the transition economies sometimes do not help in improving the living conditions of ordinary people. Rather rich resource rents turn out to be a major impediment to the emerging development of the transition economy, lessening the incentives to reform in the country. The result was the possibility of the so-called Dutch Disease, in which disproportionate growth in a certain energy sector tends to crowd out investment in other sectors of the economy. Key Words: Azerbaijan, oil, network, PSA 요약:주로 수입원유에 의존하는 한국경제의 만성적 불황은 최근 급등하고 있는 수입 원유가에 기인하는 바가 상당히 크다. 이러한 한국의 현실을 감안할 때 풍부한 유전과 가스전을 보유하고 있는 카스피해 연안의 아제르바이쟌은 일부 한국인들로부터 선망의 대상이 되고 있다. -

ENERGY TRANSIT and SECURITY IMBALANCE in SOUTH CAUCASUS: the ROAD BETWEEN RUSSIA and the EUROPEAN UNION by Tamar Pataraia

ENERGY TRANSIT AND SECURITY IMBALANCE IN SOUTH CAUCASUS: THE ROAD BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE EUROPEAN UNION by Tamar Pataraia TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 1 2. CHALLENGES TO THE SECURITY OF TRANSIT INFRASTRUCTURE IN SOUTH CAUCASUS ................................. 2 3. THE EUROPEAN UNION’S ROLE IN REACTING TO THE EXISTING CHALLENGES .............................................. 4 3.1. POLITICAL ASPECTS OF TRANSIT INFRASTRUCTURE ............................................................................. 6 4. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................................. 8 1. INTRODUCTION The political development of the countries of South Caucasus after the breakup of the Soviet Union is defined by the variety of fissures – the countries’ fragmentation through ethnic and territorial conflicts; the social and economic fragmentation of the societies, a lack of solidarity; the rise of nationalistic ideologies; the wide amplitude of the crises; striving towards and distancing from democracy in a changing frequency; and many others. The complexity of this region is further enhanced by its geographic location in-between the Middle East, Europe and Russia. However, this is not an issue of geography alone, but an issue of struggle between these large energy producing and consuming markets in order to control the energy channels. As a result of the disruption of the Soviet energy and economic space and infrastructure during the 1990s, energy and economic potential of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia were virtually nullified. Dragged into the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and a civil war, Azerbaijan found it problematic to utilise its oil resources and make it available to the external market. Armenia, as a result of fight with Azerbaijan and civil wars in Georgia, found itself completely cut off from the vital Russian energy resources.