Sherman, Joel D. Strategies for Collecting Finance Data from Private

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016–2017 Curriculum Guide

2016–2017 CURRICULUM GUIDE MARET SCHOOL | 3000 CATHEDRAL AVENUE, NW | WASHINGTON DC 20008-3498 | 202.939.8814 | WWW.MARET.ORG 3 MISSION Maret is a vibrant K-12, co-educational, independent school in Washington, DC. We ignite our students’ potential and foster their academic, artistic, and athletic talents. We develop the mind, nurture curiosity, welcome challenge, embrace joy, and build community that is equitable and inclusive. PHILOSOPHY Maret provides a vigorous and dynamic curriculum, created by a skilled faculty of life- long learners. We instill a devotion to academic excellence and a love for discovery and exploration. From our inception in 1911, Maret has adopted proven educational tenets while pursuing innovative approaches to learning. At every grade level, our students receive a broad and deep educational experience that allows them to cultivate individual strengths and interests. Maret believes that social and emotional development is central to students’ well-being and success. We encourage our students to tackle challenges in a culture of nurtured risk taking. We want them to push beyond their comfort zone so they can build resilience, character, and robust problem-solving skills. We understand the need for balance in our lives and seek opportunities to infuse our school day with moments of laughter and surprise. Maret is an inclusive community that embraces diversity of perspective, experience, identity, circumstance, and talent. Our size and single campus foster meaningful connections among students, faculty, and parents. Our historic campus and its location in the nation’s capital are integral to our program. We engage in service opportunities that enhance students’ sense of civic responsibility and leadership. -

2020 ISL Swimming & Diving Championships

Nation's Capital Swim Club HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 7.0 - 6:41 AM 1/25/2020 Page 1 2020 ISL Swimming & Diving Championships - 1/23/2020 to 1/24/2020 Results Event 1 Women 1 mtr Diving Meet: 543.35 ! 2002 Amanda Blong Sidwell Friends League: 543.35 * 2002 Amanda Blong Sidwell Friends Name Yr School Finals Score 1 Thibodeau, Genevieve S SR Stone Ridge-PV 435.70 469.30 2 Mazzara, Michelle E FR Stone Ridge-PV NP 438.60 3 Bramao, Wynter JR The Holton-Arms School 396.25 397.45 4 McDonald, Emma JR The Holton-Arms School 297.85 362.85 5 Fergusson, Claire SR St. Stephen's & St. Agnes-VA 297.10 321.25 6 Berger, Shelby SO Flint Hill School 342.75 283.45 7 Sparks, Stefany R SO Stone Ridge-PV NP 264.05 8 Korff, Alanna SO Madeira Varsity Swim and Dive-PV NP 241.95 9 Raman, Sarah SR Potomac School Swim Team-PV 228.80 239.95 10 Estes, Molly SO Madeira Varsity Swim and Dive-PV NP 218.05 11 Turnage, Danielle JR St. Stephen's & St. Agnes-VA NP 202.95 12 Ewald, Colleen Gds High School NP 202.45 --- Smith, Lyndsey The Bullis School-PV NP DQ --- Min, Lily JR Flint Hill School 303.65 DQ Event 2 Women 200 Yard Medley Relay Meet: 1:48.78 ! 1/26/2018 Stone Ridge SR -PV P Bacon, J LeFauve, T Thomas, N Kronfli League: 1:47.13 * 2017 Stone Ridge Stone Ridge Bacon, Marmolejos, Chen, Higgins Team Relay Seed Time Finals Time 1 Stone Ridge-PV A 1:46.21 1:43.62* 1) Bacon, Phoebe M SR 2) Sun, Eleanor FR 3) Gemmell, Erin M FR 4) Thomas, Tia L JR 24.52 54.57 (30.05) 1:19.86 (25.29) 1:43.62 (23.76) 2 The Holton-Arms School A 1:44.82 1:45.68* 1) Watts, Courtney FR 2) Wu, Joyce FR 3) Johnson, Jillian SR 4) Zupnik, Tatum SR 26.81 56.04 (29.23) 1:21.82 (25.78) 1:45.68 (23.86) 3 Madeira Varsity Swim and Dive-PV A 1:44.69 1:51.47 1) Watts, Molly SR 2) Davis, Sofie SR 3) Arndt, Hannah JR 4) Kelley, Niya SR 28.34 58.19 (29.85) 1:25.94 (27.75) 1:51.47 (25.53) 4 Georgetown Visitation-PV A 1:54.55 1:52.30 1) DeLuca, Caroline R JR 2) Thornett, Sydney-Cate JR 3) McNichols, Inez FR 4) Martin, Allison JR 27.58 59.84 (32.26) 1:27.30 (27.46) 1:52.30 (25.00) 5 St. -

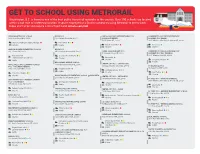

GET to SCHOOL USING METRORAIL Washington, D.C

GET TO SCHOOL USING METRORAIL Washington, D.C. is home to one of the best public transit rail networks in the country. Over 100 schools are located within a half mile of a Metrorail station. If you’re employed at a District school, try using Metrorail to get to work. Rides start at $2 and require a SmarTrip® card. wmata.com/rail AIDAN MONTESSORI SCHOOL BRIYA PCS CARLOS ROSARIO INTERNATIONAL PCS COMMUNITY COLLEGE PREPARATORY 2700 27th Street NW, 20008 100 Gallatin Street NE, 20011 (SONIA GUTIERREZ) ACADEMY PCS (MAIN) 514 V Street NE, 20002 2405 Martin Luther King Jr Avenue SE, 20020 Woodley Park-Zoo Adams Morgan Fort Totten Private Charter Rhode Island Ave Anacostia Charter Charter AMIDON-BOWEN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BRIYA PCS 401 I Street SW, 20024 3912 Georgia Avenue NW, 20011 CEDAR TREE ACADEMY PCS COMMUNITY COLLEGE PREPARATORY 701 Howard Road SE, 20020 ACADEMY PCS (MC TERRELL) Waterfront Georgia Ave Petworth 3301 Wheeler Road SE, 20032 Federal Center SW Charter Anacostia Public Charter Congress Heights BROOKLAND MIDDLE SCHOOL Charter APPLETREE EARLY LEARNING CENTER 1150 Michigan Avenue NE, 20017 CENTER CITY PCS - CAPITOL HILL PCS - COLUMBIA HEIGHTS 1503 East Capitol Street SE, 20003 DC BILINGUAL PCS 2750 14th Street NW, 20009 Brookland-CUA 33 Riggs Road NE, 20011 Stadium Armory Public Columbia Heights Charter Fort Totten Charter Charter BRUCE-MONROE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL @ PARK VIEW CENTER CITY PCS - PETWORTH 3560 Warder Street NW, 20010 510 Webster Street NW, 20011 DC PREP PCS - ANACOSTIA MIDDLE APPLETREE EARLY LEARNING CENTER 2405 Martin Luther -

Benjamin C. Bradlee

Benjamin C. Bradlee: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Bradlee, Benjamin C., 1921-2014 Title: Benjamin C. Bradlee Papers Dates: 1921-2013 Extent: 185 document boxes, 2 oversize boxes (osb) (77.7 linear feet), 1 galley file (gf) Abstract: The Benjamin C. Bradlee Papers consist of memos, correspondence, manuscript drafts, desk diaries, transcripts of interviews and speeches, clippings, legal and financial documents, photographs, notes, awards and certificates, and printed materials. These professional and personal records document Bradlee’s career at Newsweek and The Washington Post, the composition of written works such as A Good Life and Conversations with Kennedy, and Bradlee’s post-retirement activities. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-05285 Language: English and French Access: Open for research. Researchers must register and agree to copyright and privacy laws before using archival materials. Some materials are restricted due to condition, but facsimiles are available to researchers. Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchases, 2012 (12-05-003-D, 12-08-019-P) and Gift, 2015 (15-12-002-G) Processed by: Ancelyn Krivak, 2016 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Bradlee, Benjamin C., 1921-2014 Manuscript Collection MS-05285 Biographical Sketch Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee was born in Boston on August 26, 1921, to Frederick Josiah Bradlee, Jr., an investment banker, and Josephine de Gersdorff Bradlee. A descendant of Boston’s Brahmin elite, Bradlee lived in an atmosphere of wealth and privilege as a young child, but after his father lost his position following the stock market crash of 1929, the family lived without servants as his father made ends meet through a series of odd jobs. -

Oblates to Celebrate Life of Mother Mary Lange,Special Care Collection

Oblates to celebrate life of Mother Mary Lange More than 30 years before the Emancipation Proclamation, Mother Mary Lange fought to establish the first religious order for black women and the first black Catholic school in the United States. To honor the 126th anniversary of their founder’s death, the Oblate Sisters of Providence have planned a Feb. 3 Mass of Thanksgiving at 1 p.m., which will be celebrated by Cardinal William H. Keeler in the Our Lady of Mount Providence Convent Chapel in Catonsville. The Mass will be followed by a reception, offering guests the opportunity to view Mother Mary Lange memorabilia. A novena will also be held Jan. 25-Feb. 2 in the chapel. Sister M. Virginie Fish, O.S.P., and several of her colleagues in the Archdiocese of Baltimore have devoted nearly 20 years to working on the cause of canonization for Mother Mary Lange, who, along with Father James Hector Joubert, S.S., founded the Oblate Sisters in 1829. With the help of two other black women, Mother Mary Lange also founded St. Frances Academy, Baltimore, in 1828, which is the first black Catholic school in the country and still in existence. Sister Virginie said the sisters see honoring Mother Mary Lange as a fitting way to kick-start National Black History Month. Father John Bowen, S.S., postulator for Mother Mary Lange’s cause, completed the canonization application three years ago and sent it to Rome, where it is currently under review. There is no timetable for the Vatican to complete or reject sainthood for Mother Mary Lange, Father Bowen said. -

JESSICA LEE! Sheridan Is Excited to Welcome Jessica Lee, Our New Head of School

JESSICA LEE! Sheridan is excited to welcome Jessica Lee, our new head of school. Her term begins July 1st. WelcomeJessica brings with her a true commitment to academic rigor, experiential learning, diversity, and inclusivity, and the skills to make those values manifest at Sheridan. She has tremendous experience as a collaborative and empowering leader and as an adept administrator. Her focus on building strong and trusting relationships with students, faculty, staff, parents, and alumni will make her an excellent guide for Sheridan. Jessica is moving to DC from The Athenian School in Danville, California, where she is the head of middle school and assistant head of school for advancement. Prior to joining Athenian, Jessica was the head of the middle school at Gateway School in Santa Cruz, California, where she also taught algebra, geometry, American history, and English. Jessica holds an M.A. in independent school leadership from Columbia University and a B.A. in English and American literature from the University of California, Santa Cruz. Over the past several months, Jessica has oriented herself to Sheridan’s programs and operations. In addition to working closely with Adele Paynter, our acting head of school, and the Board of Trustees, Jessica has visited the Sheridan campus and has spent time in classrooms, experiencing and absorbing our SHERIDAN SCHOOL unique culture. ALUMNI NEWS During and after her visits, Jessica JUNE 2015 was impressed by our skilled faculty and staff and she noted how enthusiastic Sheridan students are about learning. “Sheridan is a wonderful school that reflects many of the very best practices in progressive education. -

Candidates for the U.S. Presidential Scholars Program January 2018

Candidates for the U.S. Presidential Scholars Program January 2018 [*] Candidate for Presidential Scholar in the Arts. [**] Candidate for Presidential Scholar in Career and Technical Education. [***]Candidate for Presidential Scholar and Presidential Scholar in the Arts [****]Candidate for Presidential Scholar and Presidential Scholar in Career and Technical Education Alabama AL - Ellie M. Adams, Selma - John T Morgan Academy AL - Kaylie M. Adcox, Riverside - Pell City High School AL - Tanuj Alapati, Huntsville - Randolph School AL - Will P. Anderson, Auburn - Auburn High School AL - Emma L. Arnold, Oxford - Donoho School The AL - Jiayin Bao, Madison - James Clemens High School AL - Jacqueline M. Barnes, Auburn - Auburn High School AL - Caroline M. Bonhaus, Tuscaloosa - Tuscaloosa Academy AL - William A. Brandyburg, Mobile - Saint Luke's Episcopal School: Upper School AL - Jordan C. Brown, Woodland - Woodland High School [**] AL - Cole Burns, Lineville - Lineville High School AL - Adelaide C. Burton, Mountain Brk - Mountain Brook High School [*] AL - Willem Butler, Huntsville - Virgil I. Grissom High School AL - Dylan E. Campbell, Mobile - McGill-Toolen Catholic High School AL - Sofia Carlos, Mobile - McGill-Toolen Catholic High School AL - Sara Carlton, Letohatchee - Fort Dale South Butler Academy [**] AL - Keenan A. Carter, Mobile - W. P. Davidson Senior High School AL - Amy E. Casey, Vestavia - Vestavia Hills High School AL - Madison T. Cash, Fairhope - Homeschool AL - Kimberly Y. Chieh, Mobile - Alabama School of Math & Science AL - Karenna Choi, Auburn - Auburn High School AL - Logan T. Cobb, Trussville - Hewitt-Trussville High School AL - Julia Coccaro, Spanish Fort - Spanish Fort High School AL - David M. Coleman, Owens Crossroad - Huntsville High School AL - Marvin C. Collins, Mobile - McGill-Toolen Catholic High School AL - Charlotte M. -

2020–2021 UPPER SCHOOL CURRICULUM GUIDE MISSION Maret Is a Vibrant, K–12, Coeducational, Independent School in Washington, DC

2020–2021 UPPER SCHOOL CURRICULUM GUIDE MISSION Maret is a vibrant, K–12, coeducational, independent school in Washington, DC. We ignite our students’ potential; foster their academic, artistic, and athletic talents; and promote their well-being. We develop the mind, nurture curiosity, welcome challenge, embrace joy, and build community that is equitable and inclusive. PHILOSOPHY Maret provides a vigorous and dynamic curriculum, created by a skilled faculty of lifelong learners. We instill a devotion to academic excellence and a love for discovery and exploration. From our inception in 1911, Maret has adopted proven educational tenets while pursuing innovative approaches to learning. At every grade level, our students receive a broad and deep educational experience that allows them to cultivate individual strengths and interests. Maret believes that social and emotional development is central to students’ well-being and success. We encourage our students to tackle challenges in a culture of nurtured risk taking. We want them to push beyond their comfort zone so they can build resilience, character, and robust problem-solving skills. We understand the need for balance in our lives and seek opportunities to infuse our school day with moments of laughter and surprise. Maret is an inclusive community that embraces diversity of perspective, experience, identity, circumstance, and talent. Our size and single campus foster meaningful connections among students, faculty, and parents. Our historic campus and its location in the nation’s capital are integral to our program. We engage in service opportunities that enhance students’ sense of civic responsibility and leadership. Students graduate from Maret well equipped to excel in future academic endeavors and to lead confident and fulfilling lives in an ever-changing world. -

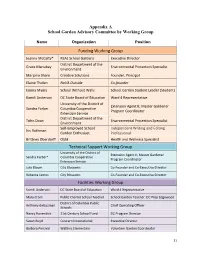

Farm to School and School Garden Report Appendix

Appendix A School Garden Advisory Committee by Working Group Name Organization Position Funding Working Group Jeanne McCarty* REAL School Gardens Executive Director District Department of the Grace Manubay Environmental Protection Specialist Environment Marjorie Share Creative Solutions Founder, Principal Elaine Tholen NoVA Outside Co-founder Emma Myers School Without Walls School Garden Student Leader (Student) Kamili Anderson DC State Board of Education Ward 4 Representative University of the District of Extension Agent II; Master Gardener Sandra Farber Columbia Cooperative Program Coordinator Extension Service District Department of the Trihn Doan Environmental Protection Specialist Environment Self-Employed School Independent Writing and Editing Iris Rothman Garden Enthusiast Professional Brittney Oberdorff OSSE Health and Wellness Specialist Technical Support Working Group University of the District of Extension Agent II; Master Gardener Sandra Farber* Columbia Cooperative Program Coordinator Extension Service Lola Bloom City Blossoms Co-Founder and Co-Executive Director Rebecca Lemos City Blossoms Co-Founder and Co-Executive Director Facilities Working Group Kamili Anderson DC State Board of Education Ward 4 Representative Mary Crom Public Charter School Teacher School Garden Teacher: DC Prep Edgewood District of Columbia Public Anthony deGuzman Chief Operating Officer Schools Nancy Huvendick 21st Century School Fund DC Program Director Susan Boyd Concern International Executive Director Barbara Percival Watkins Elementary Volunteer -

Maret College Counseling Handbook 2016-2017

Maret College Counseling Handbook 2016-2017 Maret School 3000 Cathedral Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20008 CEEB Code - 090115 Copyright © Maret School 2016 Table of Contents Our Values in the College Process Page 3 College Counseling Contacts Page 4 A Note to Parents and Guardians Page 5 The College Search: Questions, Resources, and College Visits Page 6 How Colleges Make Their Decisions Page 10 A Completed College Application Page 13 Your Academic Record/Computing GPA Page 14 Standardized Testing Page 16 Interviews Page 21 The Essay and Personal Statements Page 23 Types of College Applications Page 25 Financial Aid Page 27 Athletic Recruitment Information Page 31 Useful Readings Page 35 Taking a Gap Year Page 38 Admissions Data from Maret Page 39 2 Our Values in the College Process We in the Maret College Counseling Office are excited to embark upon the college search and application process with you and your families. We recognize that this is an important time for you. For students, this is a time of self-discovery, reflection, and thinking about who you are and who you want to be. For families, this is a major transition, as the student leaves home, perhaps for the first time, to pursue new adventures in a new setting. This handbook contains advice, important information, and activities for you to complete as you go through the college search, application, and admissions processes. Examine it carefully, as there are sections on just about every aspect of the college admissions process! Through honest self-reflection, students are able to identify institutions that will meet their needs. -

Term Potomacthe Alumni Magazine of the Potomac School • Fall 2010

The Term PotomacThe Alumni Magazine of The Potomac School • Fall 2010 The Power of Tradition Save the Date: April 29-30, 2011 The Potomac School Alumni Association and the Alumni Governing Council present Join your friends as we honor classes ending in 1 and 6. Reconnect with classmates, friends, faculty and staff. Not a milestone year? All alumni are welcome! Back to Class • May Day • All-Alumni Cocktail Party Trail Walk • Tour the Campus • and More! Want to volunteer? We need Class Reunion Chairs. Contact Laura Miller at [email protected] or 703-749-6356. For more information, go to www.potomacschool.org/alumni. Registration materials will be mailed in February ‘11. II ■ The Potomac Term Dear Potomac Community, Perhaps nothing binds us as a community as much as our Po- tomac traditions. These annual rituals and celebrations provide a connection through time with people we knew and those we have yet to meet. Ask any alum who performed in Kindergar- ten Circus, May Day or St. George and the Dragon, or com- peted in Red and Blue, and the detailed recall will astound you. Many alumni parents continue to relive those magical moments through their own children, and new parents delight in the sense of community these occasions bring. At Potomac we focus on developing exemplary habits of heart and mind, recognizing and nurturing that relationship through the learning traditions that are at the core of a Potomac education. From song to play to as- sembly to the exploration of our woods and streams, these are “everyday” kinds of traditions that also frame our school experience. -

Ssatb Member Schools in the United States Arizona

SSATB MEMBER SCHOOLS IN THE UNITED STATES ALABAMA CALIFORNIA Indian Springs School Adda Clevenger Pelham, AL San Francisco, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 4084 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1110 Saint Bernard Preparatory School, Inc. All Saints' Episcopal Day School Cullman, AL Carmel, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 6350 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1209 ARKANSAS Athenian School Danville, CA Subiaco Academy SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1414 Subiaco, AR SSAT Score Recipient Code: 7555 Bay School of San Francisco San Francisco, CA ARIZONA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1500 Fenster School Bentley School Tucson, AZ Lafayette, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 3141 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1585 Orme School Besant Hill School of Happy Valley Mayer, AZ Ojai, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 5578 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 3697 Phoenix Country Day School Brandeis Hillel School Paradise Valley, AZ San Francisco, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 5767 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1789 Rancho Solano Preparatory School Branson School Glendale, AZ Ross, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 5997 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 4288 Verde Valley School Buckley School Sedona, AZ Sherman Oaks, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 7930 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1945 Castilleja School Palo Alto, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2152 Cate School Dunn School Carpinteria, CA Los Olivos, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2170 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2914 Cathedral School for Boys Fairmont Private Schools ‐ Preparatory San Francisco, CA Academy SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2212 Anaheim, CA SSAT Score Recipient