Visitor Characteristics, Attitudes, and Use Patterns in the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex, 1970-82

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Department of the Interior Geological

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Mineral resource potential of national forest RARE II and wilderness areas in Montana Compiled by Christopher E. Williams 1 and Robert C. Pearson2 Open-File Report 84-637 1984 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. 1 Present address 2 Denver, Colorado U.S. Environmental Protection Agency/NEIC Denver, Colorado CONTENTS (See also indices listings, p. 128-131) Page Introduction*........................................................... 1 Beaverhead National Forest............................................... 2 North Big Hole (1-001).............................................. 2 West Pioneer (1-006)................................................ 2 Eastern Pioneer Mountains (1-008)................................... 3 Middle Mountain-Tobacco Root (1-013)................................ 4 Potosi (1-014)...................................................... 5 Madison/Jack Creek Basin (1-549).................................... 5 West Big Hole (1-943)............................................... 6 Italian Peak (1-945)................................................ 7 Garfield Mountain (1-961)........................................... 7 Mt. Jefferson (1-962)............................................... 8 Bitterroot National Forest.............................................. 9 Stony Mountain (LI-BAD)............................................. 9 Allan Mountain (Ll-YAG)............................................ -

Wilderness-Watcher-Summer-2021

Wilderness WILDERNESS WATCH eeping Wilderness Wild WATCHER The Quarterly Newsletter of Wilderness Watch Volume 32 • Number 2 • Summer 2021 Should We Poison the Scapegoat? by Gary Macfarlane he Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife review of actions that are done pursuant to section 4(c) and Parks (FWP) recently put forth a five- of the Wilderness Act. The extensive helicopter and other year plan to poison 67 miles of the North motorized equipment and transport proposed in this TFork of the Blackfoot River and three lakes in the project are activities that are presumptively prohibited Scapegoat Wilderness. The Scapegoat is the southern in Wilderness under Section 4(c). … If a CE can be used anchor of the famed Bob Marshall Wilderness Com- in Wilderness to exempt projects of this size and scope, plex, an area of 1.6 utilizing a wide array of million unbroken acres generally prohibited uses of designated Wil- and significantly altering derness that is home ecological processes, then to rare species such as one has to wonder if any grizzly bears, wolves, project ever would rise to and wolverines. the level of an EA or EIS in Wilderness no matter The proposal poses a how harmful. myriad of problems beyond poisoning The background behind streams and lakes this shows how ill-ad- and much of the life vised the plan is, beyond that lives in them. its inappropriate impacts There’s the 93 he- to Wilderness. There licopter flights and North Fork of the Blackfoot River, Scapegoat Wilderness. USFS were no trout or likely landings, plus the use other fish historically of motorboats, pumps, above the North Fork and gas-powered generators—all in a place where Falls. -

Native American Collections in the Archives

Examples of collections and resources supporting research about Land, Land Use, the Environment and Conservation in Montana held at Archives & Special Collections at the Mansfield Library, University of Montana-Missoula A separate list is available for collections with content focused on Forests and the Timber Products Industry. Note: In most cases links are provided from the titles of collections to the guides to those collections. The collections themselves are not digitized and therefore are not yet available online. This list is not comprehensive. Papers of Individuals and Families G. M. Brandborg Papers (1893-1977), Mss 691, 14.5 linear feet Papers of Guy M. "Brandy" Brandborg, long-time employee of the U. S. Forest Service, and Forest Supervisor of the Bitterroot National Forest from 1935-1955. The collection includes files related to Brandborg's interest in and activities related to wilderness, conservation, and watershed protection efforts in Montana, and two memorial scrapbooks documenting his activities in favor of sustainable timber harvesting and against extensive clearcutting. Stewart M. Brandborg Papers (1932-2000), Mss 699, 45.0 linear feet This collection consists of the professional papers of environmental activist Stewart M. Brandborg. A graduate of the University of Montana and the University of Idaho, Brandborg was hired as assistant conservation director for the National Wildlife Federation in 1954. In 1956 he was elected to the governing board of The Wilderness Society and in 1960 was hired as their associate executive director. He served as director of The Wilderness Society from 1964-1977. Brandborg’s papers include correspondence, research files and other documents from his time with The Wilderness Society, as well as material documenting his work with the National Wildlife Federation, the National Park Service, Wilderness Watch, and Friends of the Bitterroot (Montana.) Arnold Bolle Papers (1930-1994), Mss 600, 40.7 linear feet Arnold Bolle was a leading figure in the Montana conservation movement. -

Fire-On-Fire Interactions in Three Large Wilderness Areas

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2012 Fire-on-Fire Interactions in Three Large Wilderness Areas Casey Teske The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Teske, Casey, "Fire-on-Fire Interactions in Three Large Wilderness Areas" (2012). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 451. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/451 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FIRE-ON-FIRE INTERACTIONS IN THREE LARGE WILDERNESS AREAS By Casey C. Teske M.S., Forest Resources, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho, 2002 B.S., Chemistry, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho, 1999 Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Forestry The University of Montana Missoula, MT February 2012 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Associate Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School LLoyd P. Queen, Chair Department of Forest Management Carl A. Seielstad Department of Forest Management Ronald H. Wakimoto Department of Ecosystem and Conservation Sciences Anna Klene Department of Geography Colin Hardy Department of Forest Management Teske, Casey, Ph.D., Spring 2012 College of Forestry and Conservation Fire-on-Fire Interactions in Three Large Wilderness Areas Chairperson: Dr. -

Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex Newsletter 2020

Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex VOLUME 29 2020 Newsletter A Note from your lead Ranger 2020 Limits of Acceptable Change Meeting Canceled At the USDA Forest Service, the health and well-being of our employees and the people we serve are our top priority. The LAC (Limits of Acceptable Change) Meeting scheduled for April 4, 2020 has been canceled at this time. We remain committed to public involvement in forest management. Information about the status of the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex will be provided through our website and social media. Every one of you interested in the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex remains key for us as wilderness stewards in staying current on both land and social concerns, wilderness resource issues, and simply general observations. Your feedback on areas of interest remains appreciated! As such, the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex managers, Forest Service representatives from the Helena-Lewis and Clark, Lolo, and Flathead National Forests, and Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks representatives still look forward to hearing from you in other formats or future events. Lastly, we do plan to hold our managers meeting, albeit virtually. Good days to you. -Michael Muñoz, Ranger Rocky Mountain Ranger District, Helena-Lewis and Clark NF Introduction The Bob Marshall Wilderness complex is comprised of the Bob Marshall, Great Bear and Scapegoat designated wildernesses and also has ties with adjacent wildlands that provide the access and trailheads to the wilderness. We the managers or stewards, if you will, really value the opportunity to meet and talk with wilderness users, supporters and advocates. 2019/2020– Although we again, on the RMRD, experienced flooding events that damaged roads on NFS lands, as well as county roads, much of the remaining season was relatively quiet. -

Southwest MONTANA Visitvisit Southwest MONTANA

visit SouthWest MONTANA visitvisit SouthWest MONTANA 2016 OFFICIAL REGIONAL TRAVEL GUIDE SOUTHWESTMT.COM • 800-879-1159 Powwow (Lisa Wareham) Sawtooth Lake (Chuck Haney) Pronghorn Antelope (Donnie Sexton) Bannack State Park (Donnie Sexton) SouthWest MONTANABetween Yellowstone National Park and Glacier National Park lies a landscape that encapsulates the best of what Montana’s about. Here, breathtaking crags pierce the bluest sky you’ve ever seen. Vast flocks of trumpeter swans splash down on the emerald waters of high mountain lakes. Quiet ghost towns beckon you back into history. Lively communities buzz with the welcoming vibe and creative energy of today’s frontier. Whether your passion is snowboarding or golfing, microbrews or monster trout, you’ll find endless riches in Southwest Montana. You’ll also find gems of places to enjoy a hearty meal or rest your head — from friendly roadside diners to lavish Western resorts. We look forward to sharing this Rexford Yaak Eureka Westby GLACIER Whitetail Babb Sweetgrass Four Flaxville NATIONAL Opheim Buttes Fortine Polebridge Sunburst Turner remarkable place with you. Trego St. Mary PARK Loring Whitewater Peerless Scobey Plentywood Lake Cut Bank Troy Apgar McDonald Browning Chinook Medicine Lake Libby West Glacier Columbia Shelby Falls Coram Rudyard Martin City Chester Froid Whitefish East Glacier Galata Havre Fort Hinsdale Saint Hungry Saco Lustre Horse Park Valier Box Belknap Marie Elder Dodson Vandalia Kalispell Essex Agency Heart Butte Malta Culbertson Kila Dupuyer Wolf Marion Bigfork Flathead River Glasgow Nashua Poplar Heron Big Sandy Point Somers Conrad Bainville Noxon Lakeside Rollins Bynum Brady Proctor Swan Lake Fort Fairview Trout Dayton Virgelle Peck Creek Elmo Fort Benton Loma Thompson Big Arm Choteau Landusky Zortman Sidney Falls Hot Springs Polson Lambert Crane CONTENTS Condon Fairfield Great Haugan Ronan Vaughn Plains Falls Savage De Borgia Charlo Augusta Winifred Bloomfield St. -

Southwest MONTANA

visitvisit SouthWest MONTANA 2017 OFFICIAL REGIONAL TRAVEL GUIDE SOUTHWESTMT.COM • 800-879-1159 Powwow (Lisa Wareham) Sawtooth Lake (Chuck Haney) Horses (Michael Flaherty) Bannack State Park (Donnie Sexton) SouthWest MONTANABetween Yellowstone National Park and Glacier National Park lies a landscape that encapsulates the best of what Montana’s about. Here, breathtaking crags pierce the bluest sky you’ve ever seen. Vast flocks of trumpeter swans splash down on the emerald waters of high mountain lakes. Quiet ghost towns beckon you back into history. Lively communities buzz with the welcoming vibe and creative energy of today’s frontier. Whether your passion is snowboarding or golfing, microbrews or monster trout, you’ll find endless riches in Southwest Montana. You’ll also find gems of places to enjoy a hearty meal or rest your head — from friendly roadside diners to lavish Western resorts. We look forward to sharing this Rexford Yaak Eureka Westby GLACIER Whitetail Babb Sweetgrass Four Flaxville NATIONAL Opheim Buttes Fortine Polebridge Sunburst Turner remarkable place with you. Trego St. Mary PARK Loring Whitewater Peerless Scobey Plentywood Lake Cut Bank Troy Apgar McDonald Browning Chinook Medicine Lake Libby West Glacier Columbia Shelby Falls Coram Rudyard Martin City Chester Froid Whitefish East Glacier Galata Havre Fort Hinsdale Saint Hungry Saco Lustre Horse Park Valier Box Belknap Marie Elder Dodson Vandalia Kalispell Essex Agency Heart Butte Malta Culbertson Kila Dupuyer Wolf Marion Bigfork Flathead River Glasgow Nashua Poplar Heron Big Sandy Point Somers Conrad Bainville Noxon Lakeside Rollins Bynum Brady Proctor Swan Lake Fort Fairview Trout Dayton Virgelle Peck Creek Elmo Fort Benton Loma Thompson Big Arm Choteau Landusky Zortman Sidney Falls Hot Springs Polson Lambert Crane Condon Fairfield Great Ronan Vaughn Haugan Falls Savage De Borgia Plains Charlo Augusta CONTENTS Paradise Winifred Bloomfield St. -

June 9, 2021 by Email and Overnight Delivery Tom Vilsack Secretary U.S

June 9, 2021 By Email and Overnight Delivery Tom Vilsack Leanne Marten Secretary Regional Forester U.S. Department of Agriculture Northern Region 1400 Independence Ave. S.W. U.S. Forest Service Washington, DC 20250 26 Fort Missoula Road [email protected] Missoula, MT 59804 [email protected] [email protected] Meryl Harrell Mary Farnsworth Deputy Under Secretary Regional Forester Natural Resources and Environment Intermountain Region U.S. Department of Agriculture U.S. Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave. S.W. 324 25th Street Washington, DC 20250 Ogden, UT 84401 [email protected] [email protected] Chris French Glenn Casamassa Acting Deputy Under Secretary Regional Forester Natural Resources and Environment Pacific Northwest Region U.S. Department of Agriculture U.S. Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave. S.W. 1220 SW 3rd Avenue Washington, DC 20250 Portland, OR 97204 [email protected] [email protected] Vicki Christiansen Chief U.S. Forest Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 1400 Independence Ave. S.W. Washington, DC 20250 [email protected] Re: Petition for Regulatory Protection of Wilderness Character in Response to Idaho and Montana’s New Wolf Laws and Wolf-Removal Programs Dear Secretary Vilsack and Agriculture Department officials, This is a petition for regulatory action by the U.S. Forest Service pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 553(e) and 7 C.F.R. § 1.28. I am writing on behalf of the Center for Biological Diversity, NORTHERN ROCKIES OFFICE 313 EAST MAIN STREET BOZEMAN, MT 59715 T: 406.586.9699 F: 406.586.9695 [email protected] WWW.EARTHJUSTICE.ORG Defenders of Wildlife, Friends of the Clearwater, Humane Society of the United States, Humane Society Legislative Fund, International Wildlife Coexistence Network, Montana Wildlife Federation, Sierra Club, Western Watersheds Project, Wilderness Watch, and Wolves of the Rockies (“Petitioners”). -

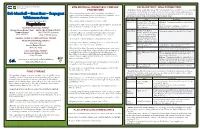

Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex Regulations (Pdf)

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service BOB MARSHALL WILDERNESS COMPLEX LOCAL DISTRICT / AREA PROHIBITIONS PROHIBITIONS • Lakeshore closures and other areas: The following lakeshores and other areas are closed to livestock use as listed below. Livestock is defined as horses, mules, llamas, and/or goats, etc. • Possessing or using a motor vehicle, motorboat, or motorized Containment is defined as tying, picketing, tethering, or hobbling animals to trees or rails by Bob Marshall ~ Great Bear ~ Scapegoat equipment except as authorized by Federal Law or regulation - 18(a). any means available such as rope, nylon, twine or plastic straps. (This includes an unmanned aerial system (drone)). Wilderness Areas Ranger District Area Prohibition Pursuant to 36 CFR 261 • Possessing or using a hang glider or bicycle - 18(b). Hungry Horse Almeda, Dickey, Elk, and All Lakes - Containment prohibited within 200 feet- • Landing of aircraft, or dropping of any material, supplies, or person by Stanton Lakes, and Tranquil (58(aa)). Regulations Basin Lakes, and Castle Creek means of aircraft, including a helicopter. - 18(c). Castle Creek River campsite - Containment FLATHEAD NATIONAL FOREST River Campsite prohibited in the entire area- (58(aa)). Spotted Bear Ranger District Hungry Horse-Glacier View • All commercial activities are prohibited in the wilderness unless Spotted Bear Flotilla, Scott, Doctor, Containment prohibited within 200 feet- (58(aa)). Ranger District (406) 758-5376 (summer) specifically authorized, including mushroom and forest product George, Koessler, Big Salmon, (406) 387-3800 (406) 387-3800 (winter) gathering, filming, and outfitting and guiding - (10(c) and (k)). Lena, Lick, Woodward, Dean and Sunburst Lakes; and all HELENA - LEWIS & CLARK NATIONAL FOREST • Leaving a fire without completely extinguishing it - 5(d). -

Purpose. Sec. 3. Designation of Wild and Scenic River

1 Title: To Amend the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act to Designate Important Headwaters Streams in 2 the Crown of the Continent and Greater Yellowstone in Montana as components of the Wild and 3 Scenic Rivers System. 4 5 6 Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in 7 Congress assembled, 8 SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. 9 This Act may be cited as the “Montana Headwaters Security Act”. 10 SEC. 2. FINDINGS; PURPOSE. 11 (a) Findings.—Congress finds that— 12 (1) The streams designated herein are cherished by the people of Montana and visitors 13 from across the United States for their clean and copious water, abundant fish and wildlife, 14 spectacular natural settings, contribution to irrigation for agriculture, and outstanding 15 recreational opportunities; 16 (2) Recreational activities (including fishing, hunting, camping, paddling, hiking, 17 swimming, rock climbing, and wildlife watching) on these streams and the surrounding land 18 generate millions of dollars annually for the local economy; 19 (3) Montana’s multi-billion dollar agricultural industry thrives on the availability of clean 20 water that originates in headwaters streams, often found on public lands; 21 (4) All streams noted herein — 22 (A) are national treasures; 23 (B) possess outstandingly remarkable values; and 24 (C) merit the high level of protection afforded by the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act 25 (16 U.S.C. 1271 et seq.) in order to maintain the benefits provided, as described in 26 paragraphs (1), (2) and (3), for future generations to enjoy; and 27 (5) Designation of select public land segments of these streams under the Wild and 28 Scenic Rivers Act (16 U.S.C. -

Wilderness in the Northern Rockies| a Missoula-Lolo National Forest Perspective

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1993 Wilderness in the northern Rockies| A Missoula-Lolo National Forest perspective Todd L. Denison The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Denison, Todd L., "Wilderness in the northern Rockies| A Missoula-Lolo National Forest perspective" (1993). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4091. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4091 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY Copying allowed as provided under provisions of the Fair Use Section of the U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW, 1976. Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's written consent. MontanaUniversity of WILDERNESS IN THE NORTHERN ROCKIES: A MISSOULA-LOLO NATIONAL FOREST PERSPECTIVE By Todd L. Denison B.A. University of Montana, 1986 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1993 Approved by Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School UMI Number: EP36297 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Wilderness Act the Wilderness Act of 1964 Established the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS) to Designate and Preserve Pristine Undeveloped Lands

Policy Brief Series Wilderness Act The Wilderness Act of 1964 established the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS) to designate and preserve pristine undeveloped lands. President Johnson and Congress recognized the importance of preserving wild lands, including wildlife habi- tat, for future generations of Americans.1 Methods 62 The Wilderness Act defines wilderness as, “an area of undeveloped federal 60 land retaining its primeval character and influence…and which generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnotice- able.” Wilderness land does not have to be virgin land, however the land should be returned to a pristine or wild condi- tion before being designated. Only ex- isting federal lands can be chosen for wilderness designation. Congress has the exclusive power to designate wilderness and to change the boundaries or un-designate a wilder- Figure 1. Number of wilderness acres designated by Congress each year (Adapted from ness area.2 Citizens can develop their Wilderness.net). own wilderness proposals and submit them directly to a member of Congress. Wilderness areas are managed by four federal agencies: the U.S. Forest Ser- vice, the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Park Service. When an area is designated as wilderness it usually continues to be managed by the same agency; for example a national forest that is designated wilderness continues to be managed by the U.S. Forest Service. Results NWPS designated 54 Wilderness Areas encompassing 9.1 million acres across 13 states at its inception in 1964.