Ronald V. Maier, MD President 2000–2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Surgery General Surgery Residency Program

Department of Surgery General Surgery Residency Program Chairman: Fabrizio Michelassi, MD, FACS Vice Chair of Education: Thomas J. Fahey, III, MD, FACS Program Director: Thomas J. Fahey, III, MD, FACS Associate Program Director: Abraham Po-Han Houng, MD Program Manager: David Fehling, MA General Surgery Residency Coordinator: Jennifer Cleaver Welcome from the Chairman We are delighted and proud to be an active part of our institution, which is among the top- ranked clinical and medical research centers in the country. Our affiliation with a major academic medical center underscores our departments three-pronged mission: to provide the highest quality of compassionate care, to educate the surgeons of tomorrow, and to pursue groundbreaking research. As members of the clinical staff of NewYork-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Medicine, our team of experienced surgeons practice at the forefront of their respective specialties, offering patients outstanding, humane and personalized care. As faculty of Weill Cornell Medical College, these physicians are educating future generations of surgeons and advancing state-of-the-art surgical treatment. The history of surgery at the New York Hospital, the second oldest hospital in the United States, reflects the evolution of surgery in America, and is marked by some of the most extraordinary achievements in medicine. The New York Hospital was the cradle of early surgical developments and instruction in America, earning a worldwide reputation for excellence and innovation. Many of today’s practices and techniques arose from our institution. Our department continues to build upon our rich legacy of surgical innovations, making important contributions to the advancement of new surgical procedures. -

Warren Commission, Volume XVII: CE

?rosidont =rived in "'.:0 1":crgency Room .: exactly 12 :43 7 ..^... in his limousine . I:o was in the back seat, Gov. Ccaally was in the front seat of the same car, Gov . Connally was brou£ht out firstand and was put in room two . ?resident was brought out next put in room one . Dr . Clark pronci :nCad the ?residort dead at the 1 p .m . exactly . All of "_esident's bolor2ings except his watch were given to the Sccrot Service . Isis W---Ch was given to Xr . 0 . P. -i a iio loft the Emergency Room, the president, at about 2 p .m . in an O'Neal ambulance . ite was put :r. a bronze colored plastic casket after hoing wrapped in a blanket and was taken out of the hospital . lie was rc:oved from the hospital, . The Gov. was taken from the Emergency Room to the Operating Room . Tha President's wife ro .-"us,:~ :o take off her bloc" grove ., clothes . She did take a tow.: and wipe her face . She took her wedding ring of- r.nc and placed. it on one of tha President's fingers. f 561 COMMISSION EXHIBIT 392 Kasi - S 20, the 2n! W H_ 1 ns in cha ,._at of his of L"O in this C". to Saa t'.1z Zzesident was Dr . jx as Ca:.:.icQ, L 3~"ido= in General surgery. !1Z . Carrico noted thL zo have .. -~a,, agGnt- raspirazory- efforts . K'a COwld a narrzbLat but found in pulse or blood to -:-- ~-ascnt . - t::-:c Z:-.c~a Z- n- ' \:a ew-tarra! wounds, one in of the in zh~ coci?ital ~:agion of terior neck, the other the were noted . -

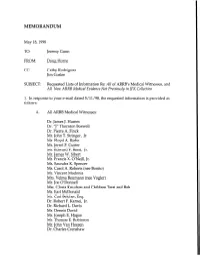

DH Memo: Requested Lists of Information

MEMORANDUM May I&l998 TO: Jeremy Gunn FROM: Doug Horne cc: Cathy Rodriguez Jim Goslee SUBJECT: Requested Lists of Information Re: All of ARRB’s Medical Witnesses, and All New ARRB Medical Evidence Not Previously in JFK Collection 1. In response to your e-mail dated 5/11/98, the requested information is provided as follows: A. All ARRB Medical Witnesses: Dr. James J. Humes Dr. “J” Thornton Boswell Dr. Pierre A. Finck Mr. John T. Stringer, Jr. Mr. Floyd A. Riebe Mr. Jerrol F. Custer Mr. Edward F. Reed, Jr. Mr. James W. Sibert Mr. Francis X. O’Neill, Jr. Ms. Saundra K. Spencer Ms. Carol A. Roberts (nee Bonito) Mr. Vincent Madonia Mrs. Velma Reumann (nee Vogler) Mr. Joe O’Donnell Mrs. Gloria Knudsen and Children Terri and Bob Mr. Earl McDonald Mr. Carl Belcher, Esq. Dr. Robert F. Karnei, Jr. Dr. Richard L. Davis Mr. Dennis David Mr. Joseph E. Hagan Mr. Thomas E. Robinson Mr. John Van Hoesen Dr. Charles Crenshaw 2 Ms. Audrey Bell (R.N.) Dr. Robert G. Grossman Dr. Paul Peters Dr. Leonard D. Saslaw, Ph.D. Mr. Robert I. Bouck Mr. Floyd Boring Mr. Donald A. Purdy, Jr., Esq. Mr. Ken Vrtacnik Mr. James Mastrovito Mr. Michael Rhode Ms. Jamie B. Taylor Children of George Burkley (Ms. Isabel Starling, Mr. Richard Burkley, Mr. George Burkley, and Ms. Nancy Denlea) Dr. Janet Travel1 Dr. James B. Rhoads, Ph.D. Ms. Eve Carr (nee Patricia Eve Walkling) Mr. Roger Boyajian Ms. Cindy C. Smolovik Ms. Lois A. Dillard Dr. John Ebersole (posthumously) B. All New ARRB Medical Evidence Not Previously in JFK Collection (Transcripts of Sworn Testimony from Depositions -

Conspiracy- - Of· Si1lence

. I JFK CONSPIRACY- - OF· SI1LENCE Charles A. Crenshaw, M.D. with Jens Hansen and J� Gary Shaw Introduction by John H. Davis (]) A SIGNET BOOK SIGNET Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books USA Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London WS STZ, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2 Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England Fust published by Signet, an imprint of New American Ubrary, a division of Penguin Books USA Inc. Fust Printing, April, 1992 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Copyright C Dr. Charles A. Crenshaw, lens Hansen, and J. Gary Shaw, 1992 Introductioncopyright C John H. Davis, 1992 AU rights reserved (/)REGISTERED TRADEMARK-MARCA REOISTRADA Printed in the United States of America Without limitingthe rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book. BOOKS ARE AVAILABLE AT QUANTITY DISCOUNI'S WHEN USED TO PROMOTE PRODUCI'S OR SERVICES. FOR INFORMATION PLEASE WRITE TO PREMIUM MARKETING DIVISION, PENGUIN BOOKS USA INC., 375 HUDSON STREET, NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10014. · If you purchased this book without a cover you should be aware that this book is stolen property. -

Doctor Regrets Fateful Words on a Sad Day in Dallas by JIMMY BRESLIN Newsday Tuesday November 18, 2003

Doctor Regrets Fateful Words on a Sad Day in Dallas By JIMMY BRESLIN Newsday Tuesday November 18, 2003 The high wind country sends its strong gusts roaring through the 20 acres of loblolly pines that are up to 14 feet since their harvesting in 1990. Raising trees is a big business in this part of Texas. The pines grow a foot and a half a year, and the wind’s sound increases as they get higher. The trees are in rows as they grow. Someday they will be for Malcolm Perry’s grandchildren, who are now 6 and 8. In a grove alongside the property, pine trees grow to 100 feet into the wind. The hardwood trees on the property, maple and oak, are scattered on hills and run down to a pond. Many of them have not been harvested. They grow 60 and 70 feet high and one tree shading the house is 75 feet. All the trees will grow, slowly, almost unnoticeably until they are high in the sky and in this place where time is measured by a tree’s step from the earth. Malcolm Perry listens to the wind coming through the trees with a low roar, or a whistle, or suddenly, a shriek that sometimes is familiar with him. The shrieks of Parkland Memorial Hospital have run through all the hallways and rooms and arenas of all the years, softening now, diminishing, but burrowing into the wind and reaching the unwilling consciousness of Dr. Malcolm Perry. He was working on John F. Kennedy’s heart when he died in Parkland Hospital on the fall day in 1963. -

American Association for the Surgery of Trauma 75Th Anniversary 1938 – 2013 American Association for the Surgery of Trauma 75Th Anniversary 1938 – 2013

American Association for the Surgery of Trauma 75th Anniversary 1938 – 2013 American Association for the Surgery of Trauma 75th Anniversary 1938 – 2013 Edited by Martin A. Croce David H. Livingston Frederick A. Luchette Robert C. Mackersie Published by The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma 633 North Saint Clair Street, Suite 2600 Chicago, Illinois 60611 www.aast.org Copyright © 2013 American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Editing and interior design by J.L. Crebs Layout and cover design by Baran Mavzer All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Control Number: 2013949405 ISBN10: 0-9898928-0-8 ISBN13: 978-0-9898928-0-3 First edition Printed in the United States of America Table of Contents Preface Robert C. Mackersie, MD..................................................................................................i Part I • The First 75 Years 1 History of the AAST Steven R. Shackford, MD..................................................................................................1 2 The AAST Gavels Robert C. Mackersie, MD................................................................................................20 3 Conception, Maturation, and Transmogrification of The Journal of Trauma Basil A. Pruitt, Jr, MD, and Ernest -

Price Ex 2-35

TOP SECRET November 23, 1963 Geo=~~ G . B;:r:;ley, tg,D, ..ashin ton, D .C . L .`2ar Dr . -Eurkley, As you requasted, i enclose an abstract of the of t.... late cent John r . Kennedy to :arkla :d `:,=worial Hospital, Da llas $ Texas . hiz su: ary is-prepared from the statements of Love-:::' ph;-Licians w::c were present and administered to statements were written the after- ::oo of the trascdy. ';e havc kept tI= .e copies of this report locally . C:;e,:gas beer, sent to the Dun's Office, The University of _~_...^.s Sout::~cstern Ycdical School, as all the physicians z r, a~:tendance hold positions there . One copy has been zo th.: medical record is Parkland Memorial Hos- pital . : have retained one copy for my files . Please accent this report with my deepest sym- at-y . Shculd ycu sec :.rs . Kennedy, would you convey t-:-Ie deep feelings of grief and sorrow of the entire o= Paraand i Tw'L1~r~G:1 Hospital . My own personal fealinlos of loss and tragedy go with this letter. Yours sincerely, Ke: p Clark, M.D . Director Service of Neurological Surgery . KC :aa cc to Den's Office, Southwestern Medical School ,/cc to 2%:edical Records, Parkland Memorial Hospital TOP SECRE"t, P&ICLr ExHIBIT No. 2 TOP SECRET S RY _l:e ?resident arrived at the Emergency Room at 12 :43 P .M ., the 22nd of November, 1953 . He was in the .,ac?: seat of his liziousirta . Governor Connally or Texas w~as al_-o in this car . -

RON J. ANDERSON, MD in First Person

RON J. ANDERSON, M.D. In First Person: An Oral History American Hospital Association Center for Hospital and Healthcare Administration History and Health Research & Educational Trust 2014 HOSPITAL ADMINISTRATION ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION RON J. ANDERSON, M.D. In First Person: An Oral History Interviewed by Kim M. Garber On February 28, 2014 Edited by Kim M. Garber Sponsored by American Hospital Association Center for Hospital and Healthcare Administration History and Health Research & Educational Trust Chicago, Illinois 2014 ©2014 by the American Hospital Association All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America Coordinated by Center for Hospital and Healthcare Administration History AHA Resource Center American Hospital Association 155 North Wacker Drive Chicago, Illinois 60606 Transcription by Chris D‟Amico Technical assistance by George R. Tafelski Photos courtesy of the American Hospital Association and Kim M. Garber EDITED TRANSCRIPT Interviewed in Dallas, Texas KIM GARBER: Today is Friday, February 28, 2014. My name is Kim Garber, and I will be interviewing Dr. Ron Anderson, a physician and professor of internal medicine, who has championed care of the medically indigent in many ways, most prominently in his three decades as President/CEO of Parkland Memorial Hospital, which is the safety net hospital for Dallas County, Texas. Dr. Anderson, it‟s great to have this opportunity to speak with you. DR. RON ANDERSON: I‟m glad to be here, thank you. GARBER: You were born in Oklahoma in 1946. What was your hometown like? ANDERSON: Chickasha was an agricultural community, with both ranching and farming, but now oil is big. There were perhaps 16,000 people when I grew up there, and there are still 16,000 today. -

Surgerynews Volume 5 No

SurgeryNews Volume 5 No. 2 Inside the Issue Chairman Message Chairman Distinguished Lecture Thomas J. Fahey III, MD I am very pleased to share with you the 2017 Fall Issue of the Department of Surgery News. In this issue, we highlight several events which took place since the th 17 Annual Hassan Naama, MD, BCh printing of the Spring issue: Memorial Lectureship Alessio Pigazzi, MD - Dr. Thomas J. Fahey III, presented at the first Chairman Distinguished Lecture. 98th ACS President Installed -We were privileged to welcome back Dr. Alessio Pigazzi Barbara Lee Bass, MD, for the 17th Annual Hassan Naama, MD, BCh, Memorial FACS, FRCS (Hon) Lectureship. - Dr. Barbara Lee Bass, the John F. and Carolyn Bookout 16th Annual Department of Surgery Presidential Endowed Chair and chair, Department of Golf Tournament Surgery at the Houston Methodist Hospital, TX, was installed as the 98th President of the American College of Surgeons. 2nd Annual Department of Surgery This issue also features many departmental events including: the 2nd Annual System-Wide Retreat Department of Surgery System-Wide Retreat, the 2nd Annual Big Apple Bootcamp, the ACS Trauma Verification celebration, the 16th Annual Golf Tournament and the 2017 Surgery Graduation. 2nd Annual In addition, we welcome new faculty, residents and fellows to the Department of Big Apple Bootcamp Surgery. We also highlight our faculty’s recent honors and awards, as well as their recent media coverage, Department of Surgery Service Milestones, and the recently completed Department floorplan renovations. American College of Surgeons Trauma Verification I hope you find this issue of interest and welcome your feedback about our E-newsletter. -

Newyork-Presbyterian Department of Surgery General Surgery

EGISTRATION NewYork-Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Center PAID PRESORTED FIRST CLASS omen and Epilepsy: Special Concerns U.S. POSTAGE NEW YORK, N.Y. W PERMIT NO. 9313 turday, May 3, 2008 • 8:00 am - 1:00 pm ase print. Women and Epileps st Name Special Concerns st Name Degree Saturday, May 3, 2008 8:00 am - 1:00 pm dress y/State/Zip ytime Phone ecialty/Affiliation mail Address Department of Surgery General Surgery Residency Program GISTRATION FEE Course Co-Directors 0.00 Fee (non-refundable check or money order) Padmaja Kandula, MD yable to: Comprehensive Epilepsy Center Chairman: Fabrizio Michelassi,Cynthia MD,L. Harden, FACS MD edit cards not accepted. Vice Chair of Education: Thomas J. Fahey, III, MD, FACS ace is limited and registration is available only Program Director: AnthonyUris Auditorium C. Watkins, MD, FACS a first-come, first-served basis. Associate Program Director:1300 York Abraham Avenue Po-Han Houng, MD AIL REGISTRATION FORM AND PAYMENT TO Program Manager: David(at 69thFehling, St.) MA therine Soto Residency Program Coordinator: Joval Wilson, BA mprehensive Epilepsy Center New York, NY ewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center 5 East 68th Street-Room K-615 4.5 AMA PRA ew York, NY 10065 Category 1 Credit(s)™ r more information call 212-746-2625 CATION is Auditorium, 1300 York Avenue (at 69th St.) K-615 Room ew York, NY 10021 • RKING let Parking is available at the East 68th Street entrance and omen d at garages located on York Avenue between 68th and th Streets. There are no vouchers for parking. -

CAREERS in ANESTHESIOLOGY Two Posthumous Memoirs

CAREERS IN ANESTHESIOLOGY Two Posthumous Memoirs M.T. JENKINS BY ADOLPH H. GIESECKE FRANCIS F. FOLDES AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY WITH - ONTRIBUTIONS BY EPHRAIM S. SIKER Ci CAREERS IN ANESTHESIOLOGY HeadquartersBuilding of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Almost one third of the three spaciousfloors is devoted to the collections of the Wood Library-Museum. (From a painting by ProfessorLeroy Vandam) - 11- CAREERS IN ANESTHESIOLOGY Two Posthumous Memoirs M.T. JENKINS, M.D. A Biography by ADOLPH H. GIESECKE, M.D. FRANCIS F. FOLDES, M.D. An Autobiography with Contributions by EPHRAIM S. SIKER, M.D. EDITED BY B. Raymond Fink Kathryn E. McGoldrick THE WOOD LIBRARY-MUSEUM OF ANESTHESIOLOGY PARK RIDGE, ILLINOIS 2000 Published By Wood Library-Museum of Anesthesiology Copyright © 2000 Wood Library-Museum of Anesthesiology All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical or electronic including recording, photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Number 97-60921 Hard Cover Edition: ISBN 1-889595-03-9 Printed in the United States of America Published by: WOOD LIBRARY-MUSEUM OF ANESTHESIOLOGY 520 N. Northwest Highway Park Ridge, Illinois 60068-2573 (847) 825-5586 / FAX 847-825-1692 [email protected] - iv TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORS' NOTE Page vii EDITORS' PREFACE TWO POSTHUMOUS MEMOIRS Page ix M.T. JENKINS, M.D. A Biography by ADOLPH H. GIESECKE, M.D. Page 1 FRANCIS F. FOLDES, M.D. An Autobiography with Contributions by EPHRAIM S. SIKER, M.D. Page 121 -- V PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE B. -

Bulletin May 2003

MAY 2003 Volume 88, Number 5 _________________________________________________________________ FEATURES Stephen J. Regnier Editor Training the rural surgeon: A proposal 13 John G. Hunter, MD, FACS, and Karen E. Deveney, MD, FACS Linn Meyer Director of Training in rural surgery: A resident’s perspective 18 Communications Garrett R. Vangelisti, MD Diane S. Schneidman Senior Editor Trauma Awareness Month offers opportunity to boost support 21 Adrienne Roberts Tina Woelke Graphic Design Specialist When a surgeon becomes a patient 24 Alden H. Harken, Victor A. Silberman, MD, FACS MD, FACS Charles D. Mabry, MD, FACS Jack W. McAninch, MD, FACS DEPARTMENTS Editorial Advisors From my perspective Tina Woelke Editorial by Thomas R. Russell, MD, FACS, ACS Executive Director 3 Front cover design Tina Woelke FYI: STAT 5 Back cover design Dateline: Washington 6 Division of Advocacy and Health Policy About the cover... Rural surgery is a wide-open What surgeons should know about... 8 field. To encourage young sur- Coding breast procedures and other cancer operations geons to explore this alternative John Preskitt, MD, FACS, Albert Bothe, Jr., MD, FACS, to big-city or academic practice and Jean A. Harris and to prepare them for the range of procedures they would encounter in pastoral settings, In compliance... 26 the Oregon Health & Science ...with HIPAA rules University, Portland, has devel- Division of Advocacy and Health Policy oped a new training program. The purposes and design of the program are discussed by John Keeping current 27 G. Hunter, MD, FACS, on page What’s new in ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice 13. Additionally, the first surgi- Erin Michael Kelly cal resident to participate in the Oregon experiment recounts his experience in a companion piece on page 18.