Urban Growth and Language Shift in County Seats in Transylvania Between 1900 and 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planul De Management Al Sitului Natura 2000 Herculian

Planul de management al sitului de interes comunitar Bazinul Ciucului de Jos ROSCI0007 Planul de Management al sitului de importanță comunitară Bazinul Ciucului de Jos ROSCI0007 Planul de management al sitului de interes comunitar Bazinul Ciucului de Jos ROSCI0007 Cuprins A. INTRODUCERE .................................................................................................................. 7 A.1. Scopul Planului de Management.................................................................................. 10 A.2. Baza legală a Planului de Management ....................................................................... 11 B.1. Informaţii Generale ...................................................................................................... 13 B.1.1. Localizare .................................................................................................................. 13 B.1.2. Cadrul legal şi administrativ pentru management ..................................................... 14 B.1.3. Procedura de elaborare, modificare și actualizare a Planului de Management ......... 21 B.1.4. Procedura de implementare a Planului de Management ........................................... 23 B.1.5. Drepturi de proprietate, administrare și folosință a terenurilor ................................. 24 B.1.6. Factorii interesaţi ....................................................................................................... 26 B.1.7. Resurse pentru management şi infrastructura .......................................................... -

Denumiri Strazi

Proiect: Activitate 1: Schimbarea denumirii străzilor din Timișoara După revoluția din 1989 noile autorități locale au procedat la recensământul străzilor din Municipiul Timișoara ocazie cu care s-au constatat anumite greșeli privind denumirea corectă a străzii dar s-a dezbătut si oportunitatea schimbării numelui unui număr însemnat de Străzi, Bulevarde si Piețe. Astfel au fost schimbate un numar de 1930 de denumiri dupa cum urmeaza: Redenumirea străzilor a avut la bază în primul rând comemorarea martirilor revoluției din decembrie 1989,un număr de străzi purtând numele martirilor revoluției printre care: . Aleea Martir Andrei Istvan0 - Denumire Veche: Rachetei - Cartier: Soarelui . Timișoara, Aleea Martir Andrei Istvan (Vezi pe harta) Aleea Martir Eugen Nagy0- Denumire Veche: Farului - Cartier: Soarelui . Timișoara, Aleea Martir Eugen Nagy (Vezi pe harta) Aleea Martir Gheorghe Cruceru0 - Denumire Veche: Matasii - Cartier: Sagului . Timișoara, Aleea Martir Gheorghe Cruceru (Vezi pe harta) Aleea Martir Gheorghe Iosub0 . Aleea Martir Gheorghe Iosub din Timisoara - Denumire Veche: Afirmarii - Cartier: Aradului Est . Timișoara, Aleea Martir Gheorghe Iosub (Vezi pe harta) Aleea Martir Ioan V. Avram0 . Aleea Martir Ioan V. Avram din Timisoara - Denumire Veche: Merisor - Cartier: Circumvalatiunii . Timișoara, Aleea Martir Ioan V. Avram (Vezi pe harta) Strada Martir Constantin Garjoaba Denumire Veche: Ursului, Cartier: Girocului Timișoara, Strada Martir Constantin Garjoaba Intrarea Martir Slobodanca Ewinger Denumire Veche: Lupului, Cartier: Girocului -

Strategia De Dezvoltare Locala a Comunei Sa Ndominic

STRATEGIA DE DEZVOLTARE LOCALA A COMUNEI SA NDOMINIC 2014-2020 Sândominic, 15 decembrie 2014 Cuprins 1. SINTEZA COORDONATORULUI 5 2. METODOLOGIA APLICATĂ 8 3. ANALIZA DE MEDIU 11 3.1. Așezarea geografică 11 3.2. Relații în teritoriu, caracteristici urbanistice 13 3.3. Infrastructura tehnico-edilitară 18 3.4. Gestionarea deșeurilor 21 3.5. Riscuri naturale 22 3.6. Resurse naturale și turistice 23 3.6.1. Arii naturale protejate 23 4. SITUAȚIA COMUNITARĂ ȘI CULTURALĂ 27 4.1. Procese demografice în comună 27 4.2. Spații, evenimente și actori culturali și comunitari 35 4.2.1. Viaţa comunitară 35 4.2.2. Valori spirituale 37 4.2.3. Lumea culturii materiale 39 4.3. Învăţământul local 40 4.4. Sistemul social şi medical 42 5. SITUAŢIE ŞI PROCESE ECONOMICE 45 5.1. Context economico-geografic 45 5.2. Resurse naturale locale şi utilizarea lor 49 5.2.1. Terenuri utilizabile în agricultură şi valorificarea lor în momentul de faţă 49 5.2.2. Gospodărirea pădurilor şi vânătoare 57 5.2.3. Valorificarea altor resurse naturale 58 5.2.4. Turismul 58 5.3. Situaţie şi procese în sectoarele economice 62 5.3.1. Structura economică a judeţului 62 5.4. Structura şi activitatea antreprenorială 64 5.4.1. Situaţia şi procese pe piaţa muncii 68 5.5. Atragerea de fonduri 69 5.1. Economia administraţiei publice locale 71 6. ANALIZA SWOT 75 7. IMAGINEA DE VIITOR A COMUNEI SÂNDOMINIC 79 8. OBIECTIVELE DE DEZVOLTARE 83 9. PRIORITĂȚI DE DEZVOLTARE 84 10. AXE PRIORITARE ȘI MĂSURI DE DEZVOLTARE 85 10.1. -

Ecoterra, No. 26, 2011 55 RELATION BETWEEN SETTLEMENT SYSTEM

Ecoterra, no. 26, 2011 RELATION BETWEEN SETTLEMENT SYSTEM AND NATURAL ENVIRONMENT IN CIUC-BASIN IN THE LAST SEVEN CENTURIES Tibor ELEKES University of Miskolc, Depatment of Geography, Hungary Abstract: In Ciuc-basin the evolution of settlement system is a centuries-old process. In 1567, 42 villages were registered. The evaluation of today’s settlement system lasted till the 20th century. In the years of 1950’s and 1960’s the scattered settlements and detached farms were declared villages. During centuries the town system had changed little. Near Miercurea-Ciuc, which had performed administrative duties for a short periods, Băile Tuşnad was declared to town in the middle of 20th century. The evaluation of settlement system, administration and environment are illustrated as a process on the 18 maps, made by myself. In this paper there are published three of them. They give a historical and stop-gap summary. Mass of facts, relating with settlements, regions, environment, administrative units placed in space can represent a base to the organising microregions in the last few years. In the same time old-centuries processes can be traced back: the natural environment was receded step by step with the evaluation of settlement systems. Keywords: settlement system, natural environment, maps. Introduction In the Carpathians the settlement-systems of intermountain basins had come into being after certain stages of development. In the process of changing settlement systems not only the role of natural features, economic and social factors are determinant, but political decisions are also important. The knowledge of the evaluation of settlements system, changing of administration and settlement-environment system plays an important role in the evaluation of settlement system and in resolving of environmental problems. -

Proces-Verbal De Desemnare a Operatorilor De Calculator Ai

3URFHVYHUEDOGHGHVHPQDUHDRSHUDWRULORUGHFDOFXODWRUDLELURXULORUHOHFWRUDOHDOHVHFĠLLORU GHYRWDUHFRQVWLWXLWHSHQWUXDOHJHUHDDXWRULWă܊LORUDGPLQLVWUD܊LHLSXEOLFHORFDOHGLQGDWDGH27 septembrie 2020, conform deciziei AEP nr. 52 din 04.09.2020, %LURXO(OHFWRUDOGH&LUFXPVFULS܊LH-XGHĠHDQăQU21 HARGHITA Nr. crt. UAT 1U6HF܊LH ,QVWLWX܊LD Nume Prenume ,QL܊LDOD )XQF܊LD WDWăOXL 1 MUNICIPIUL 1 TEATRUL MUNICIPAL ´CSIKI CÂMPEAN LIVIU-MANOLE Operator MIERCUREA-CIUC JÁTÉKSZÍN´MIERCUREA-CIUC 2 MUNICIPIUL 2 LICEUL DE ARTE ´NAGY ISTVÁN´ MIHALCEA 0$5(܇9,25(/ Operator MIERCUREA-CIUC MIERCUREA-CIUC 3 MUNICIPIUL 3 &$6$'(&8/785Ă$6,1',&$7(/25 PAP MARIA A Operator MIERCUREA-CIUC MIERCUREA-CIUC 4 MUNICIPIUL 4 ܇&2$/$*,01$=,$/Ă´NAGY IMRE´ INCZE RÉKA Operator MIERCUREA-CIUC MIERCUREA-CIUC 5 MUNICIPIUL 5 ù&2$/$*,01$=,$/ĂÄNAGY IMRE´ GABOR LORÁND Operator MIERCUREA-CIUC MIERCUREA-CIUC 6 MUNICIPIUL 6 ܇FRDOD*LPQD]LDOă´Nagy Imre´ POPESCU CRISTINA Operator MIERCUREA-CIUC 7 MUNICIPIUL 7 ܇&2$/$*,01$=,$/Ă´3(7ė), SZÁSZ Zsófia A Operator MIERCUREA-CIUC SÁNDOR´MIERCUREA-CIUC 8 MUNICIPIUL 8 ܇&2$/$*,01$=,$/Ă´3(7ė), OZSVÁTH-BERÉNYI HAJNALKA-JUDIT Operator MIERCUREA-CIUC SÁNDOR´MIERCUREA-CIUC 9 MUNICIPIUL 9 ܇&2$/$*,01$=,$/Ă´LIVIU GYÖRGY Adél A Operator MIERCUREA-CIUC REBREANU´MIERCUREA-CIUC 10 MUNICIPIUL 10 *5Ă',1,ğ$ÄNAPRAFORGÓ´ GALEA MIHAI-VLAD Operator MIERCUREA-CIUC MIERCUREA-CIUC ^ƚƌ͘^ƚĂǀƌŽƉŽůĞŽƐ͕Ŷƌ͘ϲ͕ƵĐƵƌĞƔƚŝ͕^ĞĐƚŽƌϯ͕ϬϯϬϬϴϰ 1/23 Telefon: 021.310.07.69, fax: 021.310.13.86 www.roaep.ro, e-mail: [email protected] 3URFHVYHUEDOGHGHVHPQDUHDRSHUDWRULORUGHFDOFXODWRUDLELURXULORUHOHFWRUDOHDOHVHFĠLLORU -

Some Actual Aspects About the Tourism Accomodation in Harghita County

GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites Year VII, no. 2, vol. 14, November 2014, p.158-167 ISSN 2065-0817, E-ISSN 2065-1198 Article no. 14106-162 SOME ACTUAL ASPECTS ABOUT THE TOURISM ACCOMODATION IN HARGHITA COUNTY George-Bogdan TOFAN* “Babeş-Bolyai” University, Faculty of Geography, Cluj-Napoca, 5-7 Clinicilor Street, 40006, Romania, e-mail: [email protected] Adrian NIŢĂ “Babeş-Bolyai” University, Faculty of Geography, Gheorgheni Branch, Romania, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The aim of the study is to synthetically present the tendencies of one of the most important elements of the tourism, the accommodation, within Harghita County. Analyzed for more than two decades, quantitatively it presents an evolution with different positive and negative rates. By categories, the tourist villas dominate at the beginning of the ’90s, especially in the tourist resorts of the county (Borsec, Lacu Roşu, Izvoru Mureşului, Harghita-Băi, Băile Tuşnad, Băile Homorod). Later the situation changed for newer categories, existing and functioning on private initiatives (tourist pensions, agritourist pensions, bungalows), plus for some of the classic categories, the tourist chalet, adapted for the mountain tourism, the hotel, present especially in urban settlements and several resorts (Miercurea-Ciuc, Gheorgheni, Odorheiu Secuiesc, Topliţa, Băile Tuşnad, Harghita-Băi, Borsec), the motel and the tourist stop, specific to the automobile travel. Key words: accommodation, comfort degree, villas, tourist pensions, Harghita * * * * * * INTRODUCTION Aspects about the evolution of the accommodation in Harghita County were presented before in several studies approaching the geographic domain at national level (Geografia României, Geografia Umană şi Economică, 1984), at county level (the Romanian Academy series about the Romanian Counties, Judeţul Harghita, Pişotă, Iancu, Bugă, 1976; Judeţul Harghita, Cocean et al., 2013) or in some doctoral theses regarding the mountain depressions (Şeer, 2004, Mara, 2008, Tofan, 2013). -

Timisoara Ultracentral 0 918 Str

R MPRICE Studiu de piață privind valorile minime ale imobilelor din județul Timiș - 2019 Timișoara - 300002 Str. Lucian Blaga, nr. 2, ap. 6 Tel. + 40 769 68 89 98 + 40 726 19 97 99 Fax: + 40 356 42 27 20 e-mail: [email protected] www.romprice.ro Studiu de piață privind valorile minime ale imobilelor din județul Timiș Acest studiu are ca scop estimarea valorilor de piață minime pentru fiecare tip de proprietate imobiliară, așa cum au fost enumerate mai jos și care să servească Camerei Notarilor Publici Timișoara în vederea calculării venitului impozabil rezultat din transferul proprietăților imobiliare din patrimoniul personal, a tarifului ANCPI și a onorariul notarilor publici. În elaborarea acestuia au fost avute în vedere normele legale prevăzute de Legea nr. 227/2015 privind Codul fiscal, precum și normele de aplicare a Codului Fiscal, Cap. IX, art. 33, al. 4, lit. B: “ Studiul de piață reprezintă colectarea informațiilor de pe piața imobiliară în ceea privește oferta/cererea și valorile de piață corespunzătoare proprietăților imobiliare care fac obiectul transferului dreptului de proprietate potrivit prevederilor art. 111 din Codul fiscal. Acesta trebuie să conțină informații privind valorile minime consemnate pe piața imobiliară în anul precedent în funcție de tipul proprietății imobiliare, de categoria localității unde se află situată aceasta, respectiv zone în cadrul localității/rangul localității. Studiile de piață sunt comunicate de către Camerele Notarilor Publici, după fiecare actualizare, direcțiilor generale regionale ale finanțelor publice din cadrul Agenției Naționale de Administrare Fiscală, pentru a fi utilizate începând cu data de întâi a lunii următoare primirii acestora”. Conform art. -

Evidenta-Proiectanti-Final

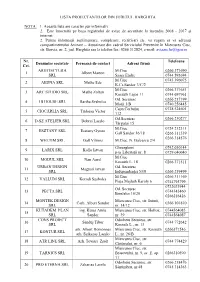

LISTA PROIECTANTILOR DIN JUDETUL HARGHITA NOTA: 1. Această lista are caracter pur informativ 2. Este întocmită pe baza registrului de avize de securitate la incendiu 2008 - 2017 şi internet. 2. Pentru informaţii suplimentare, completare, rectificări etc. vă rugam să vă adresați compartimentului Avizare – Autorizare din cadrul Serviciului Prevenire în Miercurea Ciuc, str. Borviz, nr. 2, jud. Harghita sau la telefon/fax: 0266 312824, e-mail: [email protected] Nr. Telefoane Denumire societate Persoană de contact Adresă firmă Crt. ARHITECTURA M.Ciuc 0266 371690 1 Albert Marton SRL Szasz Endre 0744 593694 M.Ciuc 0745 396075 2 AEDNA SRL Mathe Ede K.Cs.Sandor 3/C/2 M.Ciuc 0266 371651 3 ARC STUDIO SRL Mathe Zoltan Kossuth Lajos 11 0744 697961 Od. Secuiesc 0266 217199 4 1B HOUSE SRL Bartha Szabolcs Morii 1/B 0740 256445 Capu Corbului 0728 524601 5 CIOCÂRLIA SRL Tudoran Victor 112 Od.Secuiesc 0266 210277 6 D-SZ ATELIER SRL Dobrai Laszlo Târgului 15 M.Ciuc 0724 212311 7 ESZTANY SRL Esztany Gyozo Gall Sandor 16/18 0266 311539 0266 314576 8 WELTIM SRL Gall Vilmos M.Ciuc, N. Balcescu 2/4 Gheorgheni 0742 010144 9 LARIX SRL Kollo Istvan p-ţa Libertăţii nr. 8 0729 040040 M.Ciuc 10 MODUL SRL Nan Aurel Kossuth L. 18 0266 371511 URBAN DESIGN Od. Secuiesc 11 Magyari Istvan SRL Independenţei 53/8 0266 219499 M.Ciuc 0266 311169 12 VALLUM SRL Korodi Szabolcs Piaţa Majlath Karoly 6 0744793799 0732633944 Od. Secuiesc 13 PECTA SRL 0744345460 Breslelor 16/20 0266216426 MONTEK DESIGN Miercurea Ciuc, str. Inimii, 14 Carh. -

Studiu De Piaţă Judeţul Harghita

CAMERA NOTARILOR PUBLICI TÂRGU MUREŞ Târgu Mureş, str. Căprioarei, nr. 7., jud. Mureş Telefon +40 265 250 050 Fax 0372 255 097 e-mail: [email protected] STUDIU DE PIAŢĂ JUDEŢUL HARGHITA -ANUL 2020- EXPERŢILOR TEHNICI MUREŞ S.R.L. Târgu Mureş, str. Arany János, nr. 18., jud. Mureş Telefon +40 265 214 169 Fax +40 265 250 021 e-mail: [email protected] Studiu de piaţă privind valorile minime consemnate pe piaţa imobiliară - Judeţul Harghita CUPRINS Introducere 6 Capitolul 1. Prezentarea datelor 9 Apartamente situate în clădiri - blocuri de locuințe - 12 condominiu – cu destinație rezidențială Clădiri de locuit individuale (familiale) şi anexele acestora 15 Clădiri-construcţii nerezidenţiale 21 Terenuri situate în intravilanul localităţilor 30 Terenuri situate în extravilanul localităţilor 34 Capitolul 2. Tabele privind valorile minime 42 Judeţul Harghita, Circumscripţia Notarială Miercurea Ciuc 43 o Apartamente din clădiri - blocuri de locuințe - condominiu – cu 44 destinație rezidențială o Apartamente cu suprafaţă utilă ≤ 40 mp 44 o Apartamente cu suprafaţă utilă > 40 şi ≤ 70 mp 45 o Apartamente cu suprafaţă utilă >70 mp 46 o Anexe ale apartamentelor 47 o Clădiri de locuit individuale (familiale) şi anexele acestora 48 o Anexe gospodăreşti la clădirile de locuit individuale (familiale) 50 o Clădiri - costrucţii cu detinație nerezidenţială 54 o Costrucţii administrative și social-culturale 54 o Construcţii industriale și edilitare 57 o Costrucţii anexă 59 o Terenuri situate în intravilanul localităţilor 62 o Terenuri situate -

RAPORT VACCINARE.Pdf 528,1 KO

D I R E C Ţ I A D E S Ă N Ă T A T E P U B L I C Ă H A R G H I T A 530180, Miercurea-Ciuc, Str.Mikó nr. 1 tel: 0266-310423, fax: 0266-371142 e-mail: [email protected]; http://www.dspharghita.ro Nr. 1125/19.02.2021 Către, INSTITUȚIA PREFECTULUI JUDEȚUL HARGHITA Raport vaccinări COVID-19 în județul Harghita Vaccinarea împotriva COVID-19 în România se realizeză în trei etape, în care vor fi vaccinate grupele populaționale eligibile pentru etapa respectivă. Recomandările privind grupurile prioritare au fost elaborate în concordanţă cu documente emise de OMS şi ECDC în urma consultărilor de ţară realizate cu 19 ţări din Europa şi a analizei situaţiei existente în România. Recomandările STRATEGIEI DE VACCINARE ÎMPOTRIVA COVID 19 ÎN ROMÂNIA sunt în dinamică şi pot fi actualizate în funcţie de evoluţia pandemiei de COVID-19 şi de eficienţa tipurilor de vaccinuri aprobate şi disponibile pentru diferite categorii populaţionale. Aceste grupuri prioritare sunt cele care ar trebui vaccinate în prima etapă, urmând ca, odată epuizată această etapă, vaccinarea să fie disponibilă pentru toată populaţia, în vederea asigurării protecţiei faţă de formele severe şi realizării imunităţii colective, estimată în prezent la circa 70% din totalul populaţiei. (STRATEGIE din 27 noiembrie 2020 de vaccinare împotriva COVID-19 în România - MONITORUL OFICIAL nr. 1171 din 3 decembrie 2020, actualizat) Conform strategiei pentru vaccinarea împotriva COVID-19 în România vaccinarea este voluntară, ne-obligatorie și gratuită. Documentul are în vedere întregul proces și lanț de vaccinare împotriva COVID 19, de la principiile generale, până la organizarea vaccinării, depozitarea vaccinurilor, păstrarea lanțului de frig, monitorizarea siguranței și eficacității și managementul deșeurilor. -

Raport Corel 15 Final Tipar.Cdr

Building foundations 2012 for stronger communities Community foundations contribute to the for the future community foundations in transformation of local communities, so Oradea, Prahova, Bacău and Țara they can reach their development Făgărașului were also launched. potential, based on the opportunities, the resources and the ideals of their Two regional funds are also established inhabitants. They help build dynamic, based on local leadership: in Cristuru connected and supportive communities, Secuiesc, hosted by Odorheiu Secuiesc with a higher living standard. Community Foundations and in Reghin, hosted by Mureș Community Foundation. Community foundations are local organizations; they support philanthropy, The Romanian Community Foundations encourage the community spirit and offer Federation was created in 2012, as a financial support to projects from various representation platform for community areas – education, culture, environment foundation, supporting the development protection, and youth development. of philanthropy at a national level. Community foundations build funds, This report presents the framework, starting from the philanthropic interests of participants and results of a national donors, which they channel back towards support program to help develop communities as grants and scholarships. At community foundations in Romania. The the same time, they also support non- program was initiated by Association of profit organizations, initiative groups and Community Relations (ARC) and had two individuals and take leadership in building main stages so far: 2006-2008 and 2009- dialogue and cooperation platforms to 2012. address community needs or opportunities. The current stage of the program has been implemented in cooperation with The first community foundations were Romanian Environmental Partnership established in Romania five years ago in Foundation and PACT Foundation and is Cluj and Odorheiu Secuiesc. -

Nomenclator Stradal Timisoara PROPUNERE

NOMENCATORUL STRADAL AL MUNICIPIULUI TIMISOARA ANEXA NR. 4 LA HCL NR. ............. Nr. Denumire actuală Denumire veche Tip Act/an Cartier Careu Denumire an 1956 Denumire an 1946 Denumire an 1936 Denumire Sarme 1940 crt. arteră ghid 1 1 DECEMBRIE 1 DECEMBRIE STR. PA CRUCII,STAD,PL.IND.BUZ D6,D7, Muhle Wilhelm Muhle Wilhelm Muhle Wilhelm 1 Decembrie E6,F6 2 16 DECEMBRIE 1989 MARTIE ASE BV. DECIZIA260/199 IOSEFIN, ELISABET,ODOBESCU B6,B7,C5, ase Martie ase Martie ase Martie 0 C 3 20 DECEMBRIE 1989 SĂVINETI STR. HCJ 23/1993 CETATE D4, D5 Wilson Wilson 4 3 AUGUST 1919 APRILIE 12 1961 BV. DEC.505/1990 FABRIC E4, F3, F4 August 3 1919 August 3 1919 August 3 1919 5 9 MAI 9 MAI STR. CETATE D4 Eminescu Mihai 10 Mai 10 Mai 9 Mai 6 ABRUD ABRUD STR. FABRIC E3, F3 Abrud Abrud 7 ACA DE BARBU PORTIEI INTR. HCJ 23/1993 LIPOVEI VIILOR E II 8 ACAD. ALEXANDRU BORZA TRANDAFIRILOR STR. HCJ 23/1993 LOGA E4,E5,D5 Gheorghiu tefan Carp Petru Carp Petru 9 ACAD. AUREL BĂRGLĂZAN între Taborului i Semicerc STR. HCL 169/2004 BOGDĂNETILOR 10 ACAD. CORNELIU MICLOI MIRCETI PIAĂ HCJ 23/1993 FABRIC E3, F3 Miron Românul Miron Românul Miron Românul Miron 11 ACAD. DIMITRIE GUSTI BRĂILA (din Bd.Take Ionescu) STR. HCJ 23/1993 MEDICINEI E 3 Fonagy Fonagy Fonagy 12 ACAD. PETRE P. NEGULESCU BĂNCII STR. HCJ 23/1993 VIILOR E1, F1 13 ACAD. REMUS RĂDULE BOEMIA STR. HCJ 23/1993 ARADULUI EST D 1 Boemia 14 ACAD. SEXTIL PUCARIU fosta Popa Laureniu nr.9 i 11 STR.