The Good, Bad and Ugly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Topic Paper Chilterns Beechwoods

. O O o . 0 O . 0 . O Shoping growth in Docorum Appendices for Topic Paper for the Chilterns Beechwoods SAC A summary/overview of available evidence BOROUGH Dacorum Local Plan (2020-2038) Emerging Strategy for Growth COUNCIL November 2020 Appendices Natural England reports 5 Chilterns Beechwoods Special Area of Conservation 6 Appendix 1: Citation for Chilterns Beechwoods Special Area of Conservation (SAC) 7 Appendix 2: Chilterns Beechwoods SAC Features Matrix 9 Appendix 3: European Site Conservation Objectives for Chilterns Beechwoods Special Area of Conservation Site Code: UK0012724 11 Appendix 4: Site Improvement Plan for Chilterns Beechwoods SAC, 2015 13 Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI 27 Appendix 5: Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI citation 28 Appendix 6: Condition summary from Natural England’s website for Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI 31 Appendix 7: Condition Assessment from Natural England’s website for Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI 33 Appendix 8: Operations likely to damage the special interest features at Ashridge Commons and Woods, SSSI, Hertfordshire/Buckinghamshire 38 Appendix 9: Views About Management: A statement of English Nature’s views about the management of Ashridge Commons and Woods Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), 2003 40 Tring Woodlands SSSI 44 Appendix 10: Tring Woodlands SSSI citation 45 Appendix 11: Condition summary from Natural England’s website for Tring Woodlands SSSI 48 Appendix 12: Condition Assessment from Natural England’s website for Tring Woodlands SSSI 51 Appendix 13: Operations likely to damage the special interest features at Tring Woodlands SSSI 53 Appendix 14: Views About Management: A statement of English Nature’s views about the management of Tring Woodlands Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), 2003. -

Rvk-Diss Digi

University of Groningen Of dwarves and giants van Klink, Roel IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2014 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van Klink, R. (2014). Of dwarves and giants: How large herbivores shape arthropod communities on salt marshes. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 01-10-2021 Of Dwarves and Giants How large herbivores shape arthropod communities on salt marshes Roel van Klink This PhD-project was carried out at the Community and Conservation Ecology group, which is part of the Centre for Ecological and Environmental Studies of the University of Groningen, The Netherlands. -

Atlas of Yorkshire Coleoptera (Vcs 61-65)

Atlas of Yorkshire Coleoptera (VCs 61-65) Part 8 - Elateroidea - Families Eucnemidae to Cantharidae Introduction This is Part 8 of the Atlas and covers the Families Eucnemidae, Throscidae, Elateridae, Drilidae, Lycidae, Lampyridae and Cantharidae Each species in the database is considered and in each case a distribution map representing records on the database (at 1/10/2017) is presented. The number of records on the database for each species is given in the account in the form (a,b,c,d,e) where 'a' to 'e' are the number of records from VC61 to VC65 respectively. These figures include undated records (see comment on undated records in the paragraph below on mapping). As a recorder, I shall continue to use the vice-county recording system, as the county is thereby divided up into manageable, roughly equal, areas for recording purposes. For an explanation of the vice-county recording system, under a system devised in Watson (1883) and subsequently documented by Dandy (1969), Britain was divided into convenient recording areas ("vice-counties"). Thus Yorkshire was divided into vice-counties numbered 61 to 65 inclusive, and notwithstanding fairly recent county boundary reorganisations and changes, the vice-county system remains a constant and convenient one for recording purposes; in the text, reference to “Yorkshire” implies VC61 to VC65 ignoring modern boundary changes. For some species there are many records, and for others only one or two. In cases where there are five species or less full details of the known records are given. Many common species have quite a high proportion of recent records. -

(Other Than Moths) Attracted to Light

Insects (other than moths) attracted to light Prepared by Martin Harvey for BENHS workshop on 9 December 2017 Although light-traps go hand-in-hand with catching and recording moths, a surprisingly wide range of other insects can be attracted to light and appear in light-traps on a regular or occasional basis. The lists below show insects recorded from light-traps of various kinds, mostly from southern central England but with some additions from elsewhere in Britain, and based on my records from the early 1990s to date. Nearly all are my own records, plus a few of species that I have identified for other moth recorders. The dataset includes 2,446 records of 615 species. (See the final page of this document for a comparison with another list from Andy Musgrove.) This isn’t a rigorous survey: it represents those species that I have identified and recorded in a fairly ad hoc way over the years. I record insects in light-traps fairly regularly, but there are of course biases based on my taxonomic interests and abilities. Some groups that come to light regularly are not well-represented on this list, e.g. chironomid midges are missing despite their frequent abundance in light traps, Dung beetle Aphodius rufipes there are few parasitic wasps, and some other groups such as muscid © Udo Schmidt flies and water bugs are also under-represented. It’s possible there are errors in this list, e.g. where light-trapping has been erroneously recorded as a method for species found by day. I’ve removed the errors that I’ve found, but I might not yet have found all of them. -

A Review of the Beetles of Great Britain

Natural England Commissioned Report NECR134 A review of the beetles of Great Britain The Soldier Beetles and their allies Species Status No.16 First published 20 January 2014 www.gov.uk/natural-england Foreword Natural England commission a range of reports from external contractors to provide evidence and advice to assist us in delivering our duties. The views in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Natural England. Background Making good decisions to conserve species should primarily be based upon an objective process of determining the degree of threat to the survival of a species. The recognised international approach to undertaking this is by assigning the species to one of the IUCN threat categories. This report was commissioned to update the threat status of beetles from the named families from work originally undertaken in 1987, 1992 and 1994 respectively using the IUCN methodology for assessing threat. It is expected that further invertebrate status reviews will follow. Natural England Project Manager - Jon Webb, [email protected] Contractor - Buglife (project management), K.N.A. Alexander (author) Keywords - beetles, invertebrates, red list (iucn), status reviews Further information This report can be downloaded from the Natural England website: www.naturalengland.org.uk. For information on Natural England publications contact the Natural England Enquiry Service on 0845 600 3078 or e-mail [email protected]. This report is published by Natural England under the Open Government Licence - OGLv3.0 for public sector information. You are encouraged to use, and reuse, information subject to certain conditions. -

Scientific Studies in the Field of Sciences

SCIENTIFIC STUDIES IN THE FIELD OF SCIENCES EDITED BY Dr. Neslhan BAL AUTHORS Prof. Dr. İlknur DAĞ Assoc. Prof. Betül YILMAZ ÖZTÜRK Assst. Prof. Dr. Elf AKSÖZ Lecturer Dr. Bükay YENİCE GÜRSU Lecturer Dr. Dervş ÖZTÜRK Dr. Neslhan BAL Büşra ASLAN Nurbanu GÜRSOY SCIENTIFIC STUDIES IN THE FIELD OF SCIENCES EDITED BY Dr. Neslihan BAL AUTHORS Prof. Dr. İlknur DAĞ Assoc. Prof. Betül YILMAZ ÖZTÜRK Assist. Prof. Dr. Elif AKSÖZ Lecturer Dr. Bükay YENİCE GÜRSU Lecturer Dr. Derviş ÖZTÜRK Dr. Neslihan BAL Büşra ASLAN Nurbanu GÜRSOY Copyright © 2020 by iksad publishing house All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Institution of Economic Development and Social Researches Publications® (The Licence Number of Publicator: 2014/31220) TURKEY TR: +90 342 606 06 75 USA: +1 631 685 0 853 E mail: [email protected] www.iksadyayinevi.com It is responsibility of the author to abide by the publishing ethics rules. Iksad Publications – 2020© ISBN: 978-625-7139-43-4 Cover Design: İbrahim KAYA October / 2020 Ankara / Turkey Size = 16 x 24 cm CONTENTS EDITED BY PREFACE Dr. Neslihan BAL ....................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 INVESTIGATION OF MORPHOLOGICAL AND ULTRASTRUCTURAL EFFECTS OF METFORMIN ON RAT KIDNEY TISSUES Prof. Dr. İlknur DAĞ, Assoc. Prof. Betül YILMAZ ÖZTÜRK, Lecturer Dr. Bükay YENİCE GÜRSU, Büşra ASLAN, Assist. -

SYNTHESIS and PHYLOGENETIC COMPARATIVE ANALYSES of the CAUSES and CONSEQUENCES of KARYOTYPE EVOLUTION in ARTHROPODS by HEATH B

SYNTHESIS AND PHYLOGENETIC COMPARATIVE ANALYSES OF THE CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES OF KARYOTYPE EVOLUTION IN ARTHROPODS by HEATH BLACKMON Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2015 Copyright © by Heath Blackmon 2015 All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements I owe a great debt of gratitude to my advisor professor Jeffery Demuth. The example that he has set has shaped the type of scientist that I strive to be. Jeff has given me tremendous intelectual freedom to develop my own research interests and has been a source of sage advice both scientific and personal. I also appreciate the guidance, insight, and encouragement of professors Esther Betrán, Paul Chippindale, John Fondon, and Matthew Fujita. I have been fortunate to have an extended group of collaborators including professors Doris Bachtrog, Nate Hardy, Mark Kirkpatrick, Laura Ross, and members of the Tree of Sex Consortium who have provided opportunities and encouragement over the last five years. Three chapters of this dissertation were the result of collaborative work. My collaborators on Chapter 1 were Laura Ross and Doris Bachtrog; both were involved in data collection and writing. My collaborators for Chapters 4 and 5 were Laura Ross (data collection, analysis, and writing) and Nate Hardy (tree inference and writing). I am also grateful for the group of graduate students that have helped me in this phase of my education. I was fortunate to share an office for four years with Eric Watson. -

Annex K: Invertebrate Survey Report Rail Central

Ashfield Land Management Annex K: Invertebrate Survey Report Rail Central 855950 CONSULTATION DRAFT - JULY 2017 Commissioned by RSK Environment Ltd Abbey Park Humber Road Coventry CV3 4AQ RAIL CENTRAL SITE, NORTHAMPTON INVERTEBRATE SURVEY REPORT Report number BS/3015/16 October 2016 Prepared by Colin Plant Associates (UK) Consultant Entomologists 14 West Road Bishops Stortford Hertfordshire CM23 3QP 01279-507697 [email protected] Rail Central Site, Northamptonshire 2 Colin Plant Associates (UK) Invertebrate Survey Report Consultant Entomologists October 2016 Report number BS/3015/16 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Colin Plant Associates (UK) are pleased to credit the input of the following personnel: Field work for this project has been undertaken by Marcel Ashby Tristan Bantock Colin W. Plant Identification of samples has been undertaken by Marcel Ashby Tristan Bantock Peter Chandler Norman Heal Edward Milner Colin W. Plant Rail Central Site, Northamptonshire 3 Colin Plant Associates (UK) Invertebrate Survey Report Consultant Entomologists October 2016 Report number BS/3015/16 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introductory comments 1.1.1 Colin Plant Associates (UK) was commissioned on 12 th July 2016 by RSK Ltd to undertake an assessment of terrestrial invertebrate ecology at the Rail Central Site in Northamptonshire (“the site”). 1.1.2 Three sampling sessions were undertaken. An initial walkover survey of the whole site was performed on 21 st July 2016; on this date, all areas of the site were seen and most were visited, with the aim of defining the areas likely to be most representative of the whole site. 1.1.3 Invertebrate species sampling was then undertaken on the next day, 22 nd July, on 7 th August and finally on 18 th September 2016. -

Terrestrial Invertebrate Survey for Cardiff Parkway, St. Mellons, Cardiff

TERRESTRIAL INVERTEBRATE SURVEY FOR CARDIFF PARKWAY, ST. MELLONS. CARDIFF 2019 Bowden Hall, Bowden Lane, Marple, Stockport, Cheshire SK6 6ND Tel: 0161 465 8971 [email protected] www.rachelhackingecology.co.uk CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION Page 2 2. METHODOLOGY 4 3. RESULTS 7 4. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS 15 REFERENCES 16 APPENDIX 1 – TERRESTRIAL INVERTEBRATE RAW DATA 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Rachel Hacking Ecology Limited was commissioned in 2019 by Ove Arup & Partners (Arup) to undertake a terrestrial invertebrate survey of a parcel of land east of Cardiff city centre. Cardiff Parkway Developments Limited are proposing to develop a Scheme that is an Employment-led development including a new railway station and park & ride facility. An Outline Planning Application is to be made and for the following: • Railway station: New mainline train station served by Great Western Railway (GWR), Cross Country and Wales and Borders (W & B) trains; • Park & Ride facility: a car park of 500 – 2,000 spaces; • Business park: new business park accommodating 5,000 – 20,000 jobs; • Ancillary Development: Landscaping, infrastructure works (e.g. energy, water), and access. 1.2 The proposed development site lies to the east of Cardiff, in St. Mellons (O.S. gird reference: ST251808 - see Figure 1). The site currently comprises numerous reens, woodland, semi-improved grassland, arable, marshy grassland and scrub. Hendre Lake lies within the western part of the site and a main railway line bisects the site. The site lies within the Gwent Levels – Rumney & Peterstone Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). The Gwent Levels SSSI is renowned for its aquatic and terrestrial invertebrate assemblages. -

(Leptosphaeria Maculans) Among Winter

IOBC / WPRS Working Group “Integrated Control in Oilseed Crops” OILB / SROP Groupe de Travail “Lutte Intégrée en Culture d’Oléagineux” Proceedings of the meeting at Rothamsted (UK) March 30 - 31, 2004 Edited by Birger Koopmann, Neal Evans, Samantha Cook and Ingrid H. Williams IOBC wprs Bulletin Bulletin OILB srop Vol. 27 (10) 2004 The IOBC/WPRS Bulletin is published by the International Organization for Biological and Integrated Control of Noxious Animals and Plants, West Palearctic Regional Section (IOBC/WPRS) Le Bulletin OILB/SROP est publié par l‘Organisation Internationale de Lutte Biologique et Intégrée contre les Animaux et les Plantes Nuisibles, section Regionale Ouest Paléarctique (OILB/SROP) Copyright: IOBC/WPRS 2004 The Publication Commission of the IOBC/WPRS: Horst Bathon Luc Tirry Federal Biological Research Center University of Gent for Agriculture and Forestry (BBA) Laboratory of Agrozoology Institute for Biological Control Department of Crop Protection Heinrichstr. 243 Coupure Links 653 D-64287 Darmstadt (Germany) B-9000 Gent (Belgium) Tel +49 6151 407-225, Fax +49 6151 407-290 Tel +32-9-2646152, Fax +32-9-2646239 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: luc.tirry@ rug.ac.be Address General Secretariat: INRA – Centre de Recherches de Dijon Laboratoire de recherches sur la Flore Pathogène dans le Sol 17, Rue Sully, BV 1540 F-21034 DIJON CEDEX France ISBN 92-9067-172-4 i Dedication Bent Bromand in memoriam Bent Bromand, the first Convenor of the IOBC Working Group on Oilseed Rape sadly died last year. Bent was Danish and worked for most of his life as an entomologist and field trial officer at the Danish Research Centre for Plant Protection. -

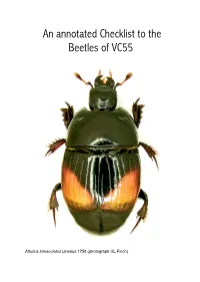

An Annotated Checklist to the Beetles of VC55

An annotated Checklist to the Beetles of VC55 Atholus bimaculatus Lineaus 1758 (photograph GL Finch) An annotated Checklist to the Beetles of VC55 Special thanks and respect must go to Derek Lott, who had solely been responsible for maintaining the database for many years on which this checklist draws so heavily upon. Forever helpful to all, regardless of ability or knowledge Derek was always happy to give advice on his favourite subject. Ever enthusiastic to promote the study of our beetles using any means he could. Although perhaps not quite up to Derek’s standard, it would be nice to think this checklist gets his approval and we are doing our bit. First edition 28th March 2015, included all known records to the end of 2014 GL Finch Revised edition February 28th 2018, includes an additional 9200 records to end of 2017 GL Finch 2 Contents Introduction 5 Sphaeriusidae 10 Elmidae 188 Gyrinidae 10 Dryopidae 189 Haliplidae 11 Limnichidae 189 Noteridae 13 Heteroceridae 190 Hygrobidae 13 Psephenidae 190 Dytiscidae 13 Ptilodactylidae 190 Carabidae 23 Eucnemidae 190 Helophoridae 49 Throscidae 191 Georissidae 51 Elateridae 191 Hydrochidae 51 Drilidae 196 Spercheidae 52 Lycidae 196 Hydrophilidae 52 Lampyridae 196 Sphaeritidae 59 Cantharidae 197 Histeridae 57 Derodontidae 201 Hydraenidae 63 Dermestidae 201 Ptilidae 65 Bostrichidae 203 Leiodae 70 Ptinidae 203 Silphidae 78 Lymexylidae 206 Staphylinidae 80 Phloiophilidae 207 Geotrupidae 174 Trogossitidae 207 Trogidae 174 Cleridae 207 Lucanidae 175 Dasytidae 208 Scarabaeidae 175 Malachiidae 209 Eucinetidae -

A Comparative Study of Arthropod Diversity on Conventional and Bt-Maize at Two Irrigation Schemes in South Africa

A comparative study of arthropod diversity on conventional and Bt-maize at two irrigation schemes in South Africa Jean-Maré Truter Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Environmental Science at the North-West University (Potchefstroom Campus) May 2011 Supervisor: J. Van den Berg Co-supervisor: H. van Hamburg i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are several people without whom this dissertation and the work it describes would not have been possible. I would like to thank all those people who have contributed towards the successful completion of this work. God our saviour who held his hand over us with every road trip we made. Without His guidance nothing I have done would have been possible. My sincere thanks to Prof. Johnnie van den Berg, my supervisor and mentor during this project. His patience, guidance, constructive criticism, sound advice and encouragement throughout the course of the study are greatly appreciated. It is due to Prof. that I have developed an interest in entomology. Prof. Huib van Hamburg, co-supervisor, thank you for your contribute and patience with all the questions and for assistance in statistical analyses. Dr. Suria Ellis of the statistical consultation service, which provided assistance with statistical analyses, a warm thanks for the time and patience. The assistance of Prof. Pieter Theron with identification of Acari is highly appreciated. Then I am truly grateful to my student colleagues that patiently helped with sampling. This work forms part of the Environmental Biosafety Cooperation Project between South Africa and Norway coordinated by the South African National Biodiversity Institute and we accordingly give due acknowledgment.