Circular Motion Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 141. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/141 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 11 Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) 11-1 Motion about a Fixed Axis The motion of the flywheel of an engine and of a pulley on its axle are examples of an important type of motion of a rigid body, that of the motion of rotation about a fixed axis. Consider the motion of a uniform disk rotat ing about a fixed axis passing through its center of gravity C perpendicular to the face of the disk, as shown in Figure 11-1. The motion of this disk may be de scribed in terms of the motions of each of its individual particles, but a better way to describe the motion is in terms of the angle through which the disk rotates. -

L-9 Conservation of Energy, Friction and Circular Motion Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Conservation of Energy Amusement Pa

L-9 Conservation of Energy, Friction and Circular Motion Kinetic energy • If something moves in • Kinetic energy, potential energy and any way, it has conservation of energy kinetic energy • kinetic energy (KE) • What is friction and what determines how is energy of motion m v big it is? • If I drive my car into a • Friction is what keeps our cars moving tree, the kinetic energy of the car can • What keeps us moving in a circular path? do work on the tree – KE = ½ m v2 • centripetal vs. centrifugal force it can knock it over KE does not depend on which direction the object moves Potential energy conservation of energy • If I raise an object to some height (h) it also has • if something has energy W stored as energy – potential energy it doesn’t loose it GPE = mgh • If I let the object fall it can do work • It may change from one • We call this Gravitational Potential Energy form to another (potential to kinetic and F GPE= m x g x h = m g h back) h • KE + PE = constant mg mg m in kg, g= 10m/s2, h in m, GPE in Joules (J) • example – roller coaster • when we do work in W=mgh PE regained • the higher I lift the object the more potential lifting the object, the as KE energy it gas work is stored as • example: pile driver, spring launcher potential energy. Amusement park physics Up and down the track • the roller coaster is an excellent example of the conversion of energy from one form into another • work must first be done in lifting the cars to the top of the first hill. -

Linear and Angular Velocity Examples

Linear and Angular Velocity Examples Example 1 Determine the angular displacement in radians of 6.5 revolutions. Round to the nearest tenth. Each revolution equals 2 radians. For 6.5 revolutions, the number of radians is 6.5 2 or 13 . 13 radians equals about 40.8 radians. Example 2 Determine the angular velocity if 4.8 revolutions are completed in 4 seconds. Round to the nearest tenth. The angular displacement is 4.8 2 or 9.6 radians. = t 9.6 = = 9.6 , t = 4 4 7.539822369 Use a calculator. The angular velocity is about 7.5 radians per second. Example 3 AMUSEMENT PARK Jack climbs on a horse that is 12 feet from the center of a merry-go-round. 1 The merry-go-round makes 3 rotations per minute. Determine Jack’s angular velocity in radians 4 per second. Round to the nearest hundredth. 1 The merry-go-round makes 3 or 3.25 revolutions per minute. Convert revolutions per minute to radians 4 per second. 3.25 revolutions 1 minute 2 radians 0.3403392041 radian per second 1 minute 60 seconds 1 revolution Jack has an angular velocity of about 0.34 radian per second. Example 4 Determine the linear velocity of a point rotating at an angular velocity of 12 radians per second at a distance of 8 centimeters from the center of the rotating object. Round to the nearest tenth. v = r v = (8)(12 ) r = 8, = 12 v 301.5928947 Use a calculator. The linear velocity is about 301.6 centimeters per second. -

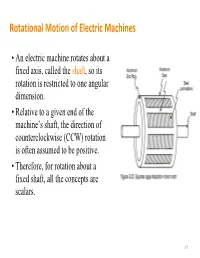

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines • An electric machine rotates about a fixed axis, called the shaft, so its rotation is restricted to one angular dimension. • Relative to a given end of the machine’s shaft, the direction of counterclockwise (CCW) rotation is often assumed to be positive. • Therefore, for rotation about a fixed shaft, all the concepts are scalars. 17 Angular Position, Velocity and Acceleration • Angular position – The angle at which an object is oriented, measured from some arbitrary reference point – Unit: rad or deg – Analogy of the linear concept • Angular acceleration =d/dt of distance along a line. – The rate of change in angular • Angular velocity =d/dt velocity with respect to time – The rate of change in angular – Unit: rad/s2 position with respect to time • and >0 if the rotation is CCW – Unit: rad/s or r/min (revolutions • >0 if the absolute angular per minute or rpm for short) velocity is increasing in the CCW – Analogy of the concept of direction or decreasing in the velocity on a straight line. CW direction 18 Moment of Inertia (or Inertia) • Inertia depends on the mass and shape of the object (unit: kgm2) • A complex shape can be broken up into 2 or more of simple shapes Definition Two useful formulas mL2 m J J() RRRR22 12 3 1212 m 22 JRR()12 2 19 Torque and Change in Speed • Torque is equal to the product of the force and the perpendicular distance between the axis of rotation and the point of application of the force. T=Fr (Nm) T=0 T T=Fr • Newton’s Law of Rotation: Describes the relationship between the total torque applied to an object and its resulting angular acceleration. -

Physics B Topics Overview ∑

Physics 106 Lecture 1 Introduction to Rotation SJ 7th Ed.: Chap. 10.1 to 3 • Course Introduction • Course Rules & Assignment • TiTopics Overv iew • Rotation (rigid body) versus translation (point particle) • Rotation concepts and variables • Rotational kinematic quantities Angular position and displacement Angular velocity & acceleration • Rotation kinematics formulas for constant angular acceleration • Analogy with linear kinematics 1 Physics B Topics Overview PHYSICS A motion of point bodies COVERED: kinematics - translation dynamics ∑Fext = ma conservation laws: energy & momentum motion of “Rigid Bodies” (extended, finite size) PHYSICS B rotation + translation, more complex motions possible COVERS: rigid bodies: fixed size & shape, orientation matters kinematics of rotation dynamics ∑Fext = macm and ∑ Τext = Iα rotational modifications to energy conservation conservation laws: energy & angular momentum TOPICS: 3 weeks: rotation: ▪ angular versions of kinematics & second law ▪ angular momentum ▪ equilibrium 2 weeks: gravitation, oscillations, fluids 1 Angular variables: language for describing rotation Measure angles in radians simple rotation formulas Definition: 360o 180o • 2π radians = full circle 1 radian = = = 57.3o • 1 radian = angle that cuts off arc length s = radius r 2π π s arc length ≡ s = r θ (in radians) θ ≡ rad r r s θ’ θ Example: r = 10 cm, θ = 100 radians Æ s = 1000 cm = 10 m. Rigid body rotation: angular displacement and arc length Angular displacement is the angle an object (rigid body) rotates through during some time interval..... ...also the angle that a reference line fixed in a body sweeps out A rigid body rotates about some rotation axis – a line located somewhere in or near it, pointing in some y direction in space • One polar coordinate θ specifies position of the whole body about this rotation axis. -

Circular Motion Dynamics

Circular Motion Dynamics 8.01 W04D2 Today’s Reading Assignment: MIT 8.01 Course Notes Chapter 9 Circular Motion Dynamics Sections 9.1-9.2 Announcements Problem Set 3 due Week 5 Tuesday at 9 pm in box outside 26-152 Math Review Week 5 Tuesday 9-11 pm in 26-152. Next Reading Assignment (W04D3): MIT 8.01 Course Notes Chapter 9 Circular Motion Dynamics Section 9.3 Circular Motion: Vector Description Position r(t) r rˆ(t) = Component of Angular ω ≡ dθ / dt Velocity z Velocity v = v θˆ(t) = r(dθ / dt) θˆ θ Component of Angular 2 2 α ≡ dω / dt = d θ / dt Acceleration z z a = a rˆ + a θˆ Acceleration r θ a = −r(dθ / dt)2 = −(v2 / r), a = r(d 2θ / dt 2 ) r θ Concept Question: Car in a Turn You are a passenger in a racecar approaching a turn after a straight-away. As the car turns left on the circular arc at constant speed, you are pressed against the car door. Which of the following is true during the turn (assume the car doesn't slip on the roadway)? 1. A force pushes you away from the door. 2. A force pushes you against the door. 3. There is no force that pushes you against the door. 4. The frictional force between you and the seat pushes you against the door. 5. There is no force acting on you. 6. You cannot analyze this situation in terms of the forces on you since you are accelerating. 7. Two of the above. -

Rotation: Moment of Inertia and Torque

Rotation: Moment of Inertia and Torque Every time we push a door open or tighten a bolt using a wrench, we apply a force that results in a rotational motion about a fixed axis. Through experience we learn that where the force is applied and how the force is applied is just as important as how much force is applied when we want to make something rotate. This tutorial discusses the dynamics of an object rotating about a fixed axis and introduces the concepts of torque and moment of inertia. These concepts allows us to get a better understanding of why pushing a door towards its hinges is not very a very effective way to make it open, why using a longer wrench makes it easier to loosen a tight bolt, etc. This module begins by looking at the kinetic energy of rotation and by defining a quantity known as the moment of inertia which is the rotational analog of mass. Then it proceeds to discuss the quantity called torque which is the rotational analog of force and is the physical quantity that is required to changed an object's state of rotational motion. Moment of Inertia Kinetic Energy of Rotation Consider a rigid object rotating about a fixed axis at a certain angular velocity. Since every particle in the object is moving, every particle has kinetic energy. To find the total kinetic energy related to the rotation of the body, the sum of the kinetic energy of every particle due to the rotational motion is taken. The total kinetic energy can be expressed as .. -

Average Angular Velocity’ As the Solution This Problem and Discusses Some Applications Briefly

Average Angular Velocity Hanno Ess´en Department of Mechanics Royal Institute of Technology S-100 44 Stockholm, Sweden 1992, December Abstract This paper addresses the problem of the separation of rota- tional and internal motion. It introduces the concept of average angular velocity as the moment of inertia weighted average of particle angular velocities. It extends and elucidates the concept of Jellinek and Li (1989) of separation of the energy of overall rotation in an arbitrary (non-linear) N-particle system. It gen- eralizes the so called Koenig’s theorem on the two parts of the kinetic energy (center of mass plus internal) to three parts: center of mass, rotational, plus the remaining internal energy relative to an optimally translating and rotating frame. Published in: European Journal of Physics 14, pp.201-205, (1993). arXiv:physics/0401146v1 [physics.class-ph] 28 Jan 2004 1 1 Introduction The motion of a rigid body is completely characterized by its (center of mass) translational velocity and its angular velocity which describes the rotational motion. Rotational motion as a phenomenon is, however, not restricted to rigid bodies and it is then a kinematic problem to define exactly what the rotational motion of the system is. This paper introduces the new concept of ‘average angular velocity’ as the solution this problem and discusses some applications briefly. The average angular velocity concept is closely analogous to the concept of center of mass velocity. For a system of particles the center of mass velocity is simply the mass weighted average of the particle velocities. In a similar way the average angular velocity is the moment of inertia weighted average of the angular velocities of the particle position vectors. -

7 Rotational Motion

7 Rotational Motion © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Slide 7-2 © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Slide 7-3 Recall from Chapter 6… . Angular displacement = θ . θ= ω t . Angular Velocity = ω (Greek: Omega) . ω = 2 π f and ω = θ/ t . All points on a rotating object rotate through the same angle in the same time, and have the same frequency. Angular velocity: all points on a rotating object have the same angular velocity, ω, but different speeds, v, and v =ωr. v =ωr © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. ω is positive if object is rotating counterclockwise. (Negative if rotation is clockwise.) . Conversion: 1 revolution = 2 π rad © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Checking Understanding Two coins rotate on a turntable. Coin B is twice as far from the axis as coin A. A. The angular velocity of A is twice that of B. B. The angular velocity of A equals that of B. C. The angular velocity of A is half that of B. © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Slide 7-13 Answer Two coins rotate on a turntable. Coin B is twice as far from the axis as coin A. A. The angular velocity of A is twice that of B. B. The angular velocity of A equals that of B. C. The angular velocity of A is half that of B. All points on the turntable rotate through the same angle in the same time. ω = θ/ t All points have the same period, therefore, all points have the same frequency. ω = 2 π f © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Slide 7-14 Checking Understanding Two coins rotate on a turntable. -

Circular Motion Angular Velocity

PHY131H1F - Class 8 Quiz time… – Angular Notation: it’s all Today, finishing off Chapter 4: Greek to me! d • Circular Motion dt • Rotation θ is an angle, and the S.I. unit of angle is rad. The time derivative of θ is ω. What are the S.I. units of ω ? A. m/s2 B. rad / s C. N/m D. rad E. rad /s2 Last day I asked at the end of class: Quiz time… – Angular Notation: it’s all • You are driving North Highway Greek to me! d 427, on the smoothly curving part that will join to the Westbound 401. v dt Your speedometer is constant at 115 km/hr. Your steering wheel is The time derivative of ω is α. not rotating, but it is turned to the a What are the S.I. units of α ? left to follow the curve of the A. m/s2 highway. Are you accelerating? B. rad / s • ANSWER: YES! Any change in velocity, either C. N/m magnitude or speed, implies you are accelerating. D. rad • If so, in what direction? E. rad /s2 • ANSWER: West. If your speed is constant, acceleration is always perpendicular to the velocity, toward the centre of circular path. Circular Motion r = constant Angular Velocity s and θ both change as the particle moves s = “arc length” θ = “angular position” when θ is measured in radians when ω is measured in rad/s 1 Special case of circular motion: Uniform Circular Motion A carnival has a Ferris wheel where some seats are located halfway between the center Tangential velocity is and the outside rim. -

Lecture 24 Angular Momentum

LECTURE 24 ANGULAR MOMENTUM Instructor: Kazumi Tolich Lecture 24 2 ¨ Reading chapter 11-6 ¤ Angular momentum n Angular momentum about an axis n Newton’s 2nd law for rotational motion Angular momentum of an rotating object 3 ¨ An object with a moment of inertia of � about an axis rotates with an angular speed of � about the same axis has an angular momentum, �, given by � = �� ¤ This is analogous to linear momentum: � = �� Angular momentum in general 4 ¨ Angular momentum of a point particle about an axis is defined by � � = �� sin � = ��� sin � = �-� = ��. � �- ¤ �⃗: position vector for the particle from the axis. ¤ �: linear momentum of the particle: � = �� �⃗ ¤ � is moment arm, or sometimes called “perpendicular . Axis distance.” �. Quiz: 1 5 ¨ A particle is traveling in straight line path as shown in Case A and Case B. In which case(s) does the blue particle have non-zero angular momentum about the axis indicated by the red cross? A. Only Case A Case A B. Only Case B C. Neither D. Both Case B Quiz: 24-1 answer 6 ¨ Only Case A ¨ For a particle to have angular momentum about an axis, it does not have to be Case A moving in a circle. ¨ The particle can be moving in a straight path. Case B ¨ For it to have a non-zero angular momentum, its line of path is displaced from the axis about which the angular momentum is calculated. ¨ An object moving in a straight line that does not go through the axis of rotation has an angular position that changes with time. So, this object has an angular momentum. -

Rotational Motion and Angular Momentum 317

CHAPTER 10 | ROTATIONAL MOTION AND ANGULAR MOMENTUM 317 10 ROTATIONAL MOTION AND ANGULAR MOMENTUM Figure 10.1 The mention of a tornado conjures up images of raw destructive power. Tornadoes blow houses away as if they were made of paper and have been known to pierce tree trunks with pieces of straw. They descend from clouds in funnel-like shapes that spin violently, particularly at the bottom where they are most narrow, producing winds as high as 500 km/h. (credit: Daphne Zaras, U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Learning Objectives 10.1. Angular Acceleration • Describe uniform circular motion. • Explain non-uniform circular motion. • Calculate angular acceleration of an object. • Observe the link between linear and angular acceleration. 10.2. Kinematics of Rotational Motion • Observe the kinematics of rotational motion. • Derive rotational kinematic equations. • Evaluate problem solving strategies for rotational kinematics. 10.3. Dynamics of Rotational Motion: Rotational Inertia • Understand the relationship between force, mass and acceleration. • Study the turning effect of force. • Study the analogy between force and torque, mass and moment of inertia, and linear acceleration and angular acceleration. 10.4. Rotational Kinetic Energy: Work and Energy Revisited • Derive the equation for rotational work. • Calculate rotational kinetic energy. • Demonstrate the Law of Conservation of Energy. 10.5. Angular Momentum and Its Conservation • Understand the analogy between angular momentum and linear momentum. • Observe the relationship between torque and angular momentum. • Apply the law of conservation of angular momentum. 10.6. Collisions of Extended Bodies in Two Dimensions • Observe collisions of extended bodies in two dimensions. • Examine collision at the point of percussion.