Human Rights Violations Consequent to Transshipment Practices in Fisheries Chelsey F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAF-06-03 Program to Monitor Transshipments At

INTER-AMERICAN TROPICAL TUNA COMMISSION COMMITTEE ON ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE 6th MEETING San Diego, California (USA) 20 August 2018 DOCUMENT CAF-06-03 CORR. IMPLEMENTATION OF THE IATTC REGIONAL OBSERVER PROGRAM FOR TRANSSHIPMENTS AT SEA 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Implementation and operation .............................................................................................................. 1 3. Results to date ...................................................................................................................................... 3 4. Financing .............................................................................................................................................. 6 5. Pending issues ...................................................................................................................................... 8 1. INTRODUCTION The IATTC observer program to monitor transshipments at sea by carrier vessels in the eastern Pacific Ocean (EPO) is regulated by Resolution C-12-07. It started in January 2009, and it will have operated for nine and a half years by August 2018. In 2016, with the approval of the Members that currently participate in the program, the Secretariat signed a three-year contract with the Marine Resources Assessment Group (MRAG) consortium for operating the program through 2019. The rates MRAG charges for services are fixed for the duration -

Compliance and Enforcement for the Exclusive Economic Zone Fisheries Management in the United Republic of Anzaniat

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 11-4-2018 Compliance and enforcement for the exclusive economic zone fisheries management in the United Republic of anzaniaT Christian Alphonce Nzowa Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Economic Policy Commons Recommended Citation Nzowa, Christian Alphonce, "Compliance and enforcement for the exclusive economic zone fisheries management in the United Republic of Tanzania" (2018). World Maritime University Dissertations. 682. https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/682 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non-commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmö, Sweden COMPLIANCE AND ENFORCEMENT FOR THE EXCLUSIVE ECONOMIC ZONE FISHERIES MANAGEMENT IN THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA By CHRISTIAN ALPHONCE NZOWA Tanzania A dissertation submitted to the World Maritime University in partial Fulfillment of the requirement for the award of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In MARITIME AFFAIRS (OCEAN SUSTAINABILITY GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT) 2018 Copyright: Christian Alphonce Nzowa, 2018 Declaration I certify that all the material in the dissertation that is not my own work has been identified, and that no material is included for which a degree has previously been conferred on me.The content of this dissertation reflect my own personal views, and are not necessarily endorsed by the University. -

Shining a Light on High Seas Transhipment: the Need to Strengthen Observer Reporting of Transhipments in the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission

Hastings Environmental Law Journal Volume 26 Number 2 Summer 2020 Article 2 2020 Shining a Light on High Seas Transhipment: The Need to Strengthen Observer Reporting of Transhipments in the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission Chris Wold Alfred “Bubba” Cook Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_environmental_law_journal Part of the Environmental Law Commons Recommended Citation Chris Wold and Alfred “Bubba” Cook, Shining a Light on High Seas Transhipment: The Need to Strengthen Observer Reporting of Transhipments in the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission, 26 Hastings Envt'l L.J. 185 (2019) Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_environmental_law_journal/vol26/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Environmental Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HASTINGS ENVIRONMENTAL LAW JOURNAL (DO NOT DELETE) 11/01/19 Shining a Light on High Seas Transhipment: The Need to Strengthen Observer Reporting of Transhipments in the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission Chris Wold* & Alfred “Bubba” Cook** I. Introduction The oceans are “enormously wide, deep and nontransparent.”1 Light rapidly dissipates beyond a depth of 200 meters,2 hiding the valuable tuna, swordfish, and other marine fish stocks sought by a global fleet of 4.6 million vessels.3 But the oceans also hide a multitude of sins, including illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, human rights violations, wildlife smuggling, and drug and gun smuggling.4 At the United Nations Security Council, transnational crime on the oceans has been linked to conflicts in Africa, millions of dollars of lost revenue, the spread of weapons, and drug and human trafficking.5 Nowhere is the ability to hide more true than the immense Western and Central Pacific Ocean. -

Page 1841 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1857

Page 1841 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1857 to that State and that is not registered under the laws (A) to violate any provision of this chapter of that State, except a law regulating landings. or any regulation or permit issued pursuant ‘‘(d) STATE PERMIT OR TREATY RIGHT REQUIRED.—No to this chapter; vessel may harvest or process Dungeness crab in the ex- (B) to use any fishing vessel to engage in clusive economic zone adjacent to the State of Wash- ington, Oregon, or California, except as authorized by a fishing after the revocation, or during the permit issued by any of those States or pursuant to any period of suspension, of an applicable permit tribal treaty rights to Dungeness crab pursuant to the issued pursuant to this chapter; decision in United States v. Washington, D.C. No. (C) to violate any provision of, or regula- CV–70–09213. tion under, an applicable governing inter- ‘‘(e) STATE AUTHORITY OTHERWISE PRESERVED.—Ex- national fishery agreement entered into pur- cept as expressly provided in this section, nothing in suant to section 1821(c) of this title; this section reduces the authority of any State under (D) to refuse to permit any officer author- the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Man- ized to enforce the provisions of this chapter agement Act (16 U.S.C. 1801 et seq.) to regulate fishing, fish processing, or landing of fish. (as provided for in section 1861 of this title) ‘‘(f) TERMINATION OF AUTHORITY.—The authority of to board a fishing vessel subject to such per- the States of Washington, Oregon, and California under son’s control for purposes of conducting any this section with respect to a Dungeness crab fishery search or inspection in connection with the shall expire on the effective date of a fishery manage- enforcement of this chapter or any regula- ment plan for the fishery under the Magnuson-Stevens tion, permit, or agreement referred to in Fishery Conservation and Management Act [16 U.S.C. -

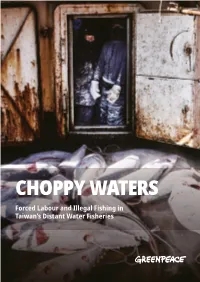

Choppy Waters Report

CHOPPY WATERS Forced Labour and Illegal Fishing in Taiwan’s Distant Water Fisheries TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 2 2. Introduction 3 Published in March 2020 by: Greenpeace East Asia 3. Methodology 6 No.109, Sec. 1, Chongqing S. Rd, Zhongzheng Dist., Taipei City 10045, Taiwan This report is written by Greenpeace East Asia (hereafter re- 4. Findings 8 ferred to as Greenpeace) to assist public education and scien- Indications of forced labour in Taiwan’s distant water fisheries: Cases and evidence 9 tific research, to encourage press coverage and to promote Reports of the fisher story 9 the awareness of environmental protection. Reading this report is considered as you have carefully read and fully un- Reports of abusive working and living conditions 12 derstand this copyright statement and disclaimer, and agree Possible violations of international standards and Taiwanese labour regulations 13 to be bound by the following terms. Potential cases of IUU fishing 18 Copyright Statement: Potential at-sea transshipments based on AIS records 19 This report is published by Greenpeace. Greenpeace is the exclusive owner of the copyright of this report. 5. How tainted tuna catch could enter the market 22 Disclaimer: FCF’s global reach 22 1. This report is originally written in English and translated How tainted catch might enter the global supply chain via FCF 23 into Chinese subsequently. In case of a discrepancy, the English version prevails. 2. This report is ONLY for the purposes of information sha- ring, environmental protection and public interests. There- 6. Taiwan’s responsibilities 25 fore should not be used as the reference of any investment The international environmental and social responsibility of seafood companies 27 or other decision-making process. -

Vanuatu Monitoring, Control, Surveillance (Mcs) and Inspection Plan

“Our Fish, Our Future” VANUATU MONITORING, CONTROL, SURVEILLANCE (MCS) AND INSPECTION PLAN Government of the Republic of Vanuatu Fisheries Department Page 1 of 14 Table of Contents 1. CONTEXT ............................................................................................................................................... 3 2. VISION ................................................................................................................................................... 4 3. GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ....................................................................................................................... 4 4. MONITORING MECHANISM .................................................................................................................. 6 4.1 Observer Program ......................................................................................................................... 6 4.2 High seas transshipment ............................................................................................................... 6 4.3 Vessel monitoring system ............................................................................................................. 7 4.4 Data collection and reporting ....................................................................................................... 7 5. OPERATIONAL REQUIREMENTS ............................................................................................................ 7 5.1 Human resource ........................................................................................................................... -

A Global Analysis to Explore the Links Between Tuna Diversity And

Tuna and transshipment: a global analysis to explore the links between tuna diversity and transshipment vessel location By Claire Christie Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Environmental Science and Environmental Sustainability and Society At Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia © Copyright by Claire Christie, 2017 Linkages between tuna diversity and transshipment vessel location 2 DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY AUTHOR: Claire Christie DATE: April 17th, 2017 TITLE: Tuna and transshipment: a global analysis to explore the links between tuna diversity and transshipment vessel location DEPARTMENT OR SCHOOL: College of Sustainability DEGREE: Bachelor of Arts Convocation: May, 2018 Environmental Science and Environment, Sustainability and Society Permission is herewith granted to Dalhousie University to circulate and to have copied for non- commercial purposes, at its discretion, the above title upon the request of individuals or institutions. I understand that my thesis will be electronically available to the public. The author reserves other publication rights, and neither the thesis nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author’s written permission. The author attests that permission has been obtained for the use of any copyrighted material appearing in the thesis (other than the brief excerpts requiring only proper acknowledgement in scholarly writing), and that all such use is clearly acknowledged. Claire Christie Signature of Author Linkages between tuna diversity and transshipment vessel location 3 Abstract Transshipment at sea is a practice where refrigerated cargo vessels, also known as reefers, meet with fishing boats to exchange catch, fresh water, food and crew. Transshipment makes economic sense as it greatly extends the time a vessel can spend at sea fishing. -

1 12-06 Gen Recommendation by Iccat on a Programme

12-06 GEN RECOMMENDATION BY ICCAT ON A PROGRAMME FOR TRANSSHIPMENT TAKING ACCOUNT of the need to combat illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing activities because they undermine the effectiveness of the conservation and management measures already adopted by ICCAT; EXPRESSING GRAVE CONCERN that organized tuna laundering operations have been conducted and a significant amount of catches by IUU fishing vessels have been transshipped under the names of duly licensed fishing vessels; IN VIEW THEREFORE OF THE NEED to ensure the monitoring of the transshipment activities by large- scale pelagic longline vessels (LSPLVs) in the Convention area, including the control of their landings; TAKING ACCOUNT of the need to ensure collection of catch data from such LSPLVs to improve the scientific assessments of those stocks; THE INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION FOR THE CONSERVATION OF ATLANTIC TUNAS (ICCAT) RECOMMENDS THAT: SECTION 1. GENERAL RULES 1. Except under the program to monitor transshipment at sea established in Section 2 below, all transshipment operations: a) within the Convention area of tuna and tuna-like species and other species caught in association with these species, and b) outside the Convention area of tuna and tuna-like species and other species caught in association with these species that were harvested in the ICCAT Convention area, must take place in port. 2. The flag Contracting Party, Cooperating non-Contracting Party, Entity or Fishing Entity (hereafter referred to as CPCs) shall take the necessary measures to ensure that fishing vessels flying their flag comply with the obligations set out in Annex 3, when transshipping tuna and tuna-like species and any other species caught in association with these species in port. -

Best Practices for At-Sea Transshipment Regulation

Best Practices for At-Sea Transshipment Regulation June 30, 2020 Holly Koehler Vice President for Policy and Outreach GTA Webinar [email protected] Transshipment At Sea • Widely used in distant water longline tuna fishing fleets • Reduces operational costs • Maximizes time on fishing grounds ▪ No RFMO has a complete prohibition of at-sea transshipment ▪ Tropical tuna RFMOs (IATTC, ICCAT, WCPFC, IOTC) General prohibition of at-sea transshipment for certain gear types (PS) Rules to permit at-sea transshipment by other specific gear types/vessel types (LSLL mostly) under certain conditions/rules Issues with At-Sea Transshipment § Takes place far from land or ports ? § There is a lack of effective monitoring, control, verification & management of at sea- transshipment § The result is that transshipment ? at sea can occur in a black box increasing risks of IUU activities Misreporting of catch Non-reporting of data Overfishing quotas or catch limits Fishing in closed or restricted areas Non-compliance with bycatch measures Labor and human rights issues Issues with Transshipment At Sea INCREASING GLOBAL USE Issues with Transshipment At Sea WEAK COMPLIANCE ▪ EXAMPLE: In IOTC, in 2018: § Out of 1300+ t/ship events there were ~250 reported infractions § 62% level of compliance with IOTC rules § 6 out of 7 fleets that transshipped (86%) had vessels with one or more repeated infringements INSUFFICIENT RFMOs REGULATIONS ▪ EXAMPLE: In IATTC, at-sea transshipment increased significantly (67% jump between 2012–2017)… but its transshipment measure -

Fish Species Transshipped at Sea (Saiko Sh) in Ghana with a Note On

Fish species transshipped at sea (Saiko ƒsh) in Ghana with a note on implications for marine conservation Denis Worlanyo Aheto ( [email protected] ) Centre for Coastal Management - Africa Centre of Excellence in Coastal Resilience (ACECoR), University of Cape Coast, Ghana https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5722-1363 Isaac Okyere ( [email protected] ) Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, School of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Coast, Ghana https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8725-1555 Noble Kwame Asare Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, School of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Coast, Ghana Jennifer Eshilley Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, School of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Coast, Ghana Justice Odoiquaye Odoi Nature Today, A25 Standards Estates, Sakumono, Tema, Ghana Research Article Keywords: Fish transshipment, saiko, IUU ƒshing, Marine Conservation, Sustainability, Ghana DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-41329/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/18 Abstract Increasing global seafood demand over the last couple of decades has resulted in overexploitation of certain ƒsh species by both industrial and small-scale artisanal ƒshers. This phenomenon has threatened the livelihoods and food security of small-scale ƒshing communities especially in the West African sub- region. In Ghana, ƒsh transshipment (locally referred to as saiko) has been catalogued as one more negative practice that is exacerbating an already dire situation. The goal of this study was to characterise transshipped ƒsh species landed in Ghana on the basis of composition, habitat of origin, maturity and conservation status on the IUCN list of threatened species to enhance understanding of the ecological implications of the practice and inform regulatory enforcement and policy formulation. -

A Comparative Analysis of AIS Data with Reported Transshipments Occurring in the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission Convention Area in 2018

A Comparative Analysis of AIS Data with Reported Transshipments Occurring in the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission Convention Area in 2018 1 Acknowledgements This report was funded in part by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and produced in cooperation with The Pew Charitable Trusts (“Pew”). The authors would like to thank Mark Young, Executive Director of the International Monitoring, Control, and Surveillance (IMCS) Network, and Claire van der Geest for reviewing this study. Prepared by: Global Fishing Watch 2 AIS-Detected Transshipment Activity Occurring in the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission Convention Area in 2018 Transshipment of catch at-sea is a major part of the global fishing industry, particularly the tuna sector. However, existing monitoring and regulatory controls over transshipment at-sea are widely considered insufficient, with no guarantee that all transfers are being reported or observed in accordance with Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) Conservation and Management Measures (CMMs). Ineffective and/or incomplete monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS) of at-sea transshipment creates opportunities for illegally caught seafood to enter the supply chain, and may perpetuate human rights abuses aboard vessels and provide an enabling environment for other illicit activities. To increase the transparency and understanding of at-sea transshipment activities, Global Fishing Watch (GFW), in partnership with The Pew Charitable Trusts (Pew), is undertaking an assessment of at-sea transshipment activities occurring inside the Convention Areas of the five global tuna RFMOs. Together, GFW and Pew have also launched the Carrier Vessel Portal (CVP). The first of its kind, the CVP is a publicly facing tool focused on at-sea transshipment, that seeks to provide policymakers, authorities, fleet operators, and other fisheries stakeholders information on when and where at-sea transshipment activities are occurring. -

Competence-Based Approaches for Fisheries Enforcement Officers

POLICY NOTES Competence-Based Approaches for Fisheries Enforcement Officers Presentation By: Kyei Kwadwo YAMOAH Friends of the Nation Importance of Fisheries • About 10 % of Ghana’s population is dependent on the Fisheries sector - direct employment & support services • Fish is a cheap source of protein – providing 60% of animal protein to Ghanaians • High fish per capita consumption of Ghana - 23-25 kg/person/yr against the world average of 13 kg • Multi-million $$ value of fish exports to the EU market Urgently need to protect the resources to prevent a total collapse of the fisheries Major Issues in the Fisheries • Overcapitalization and open access – Increasing numbers of fishing fleet – No licensing in the artisanal sector – Subsidy on fishing inputs for artisanal fishers • Use of unapproved methods of fishing – Undersized mesh & monofilament nets – Chemical and explosives fishing – Light fishing • Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU)fishing – Fishing for undersized/juvenile fish & marine protected species – Unsupervised transshipment at sea – Discard of fish at sea (as by catch) Common Offenses by Fleets Industrial Sector Trawling in the IEZ Tampering with the VMS Semi-industrial/Inshore equipment Use of light/FADs Use of undersized mesh nets Fishing without licenses Use of top-side chafers Artisanal Sector Mesh size problems Transshipment Use of unapproved gears Failure to log operations Building new boats without authorization Use of light /FADs Use of explosives Use of noxious substances 2,000,000 Out of Court Settled Infractions 50 1,800,000 45 44 1,600,000 40 1,400,000 35 1,200,000 30 1,000,000 25 Fines Fines (GHS) 800,000 20 No.of Cases 600,000 15 14 400,000 10 8 6 200,000 5 4 2 0 0 Fishing Canoe light Fishing illegally Undersized Transhipment 30m depth without license fishing in foreign mesh waters Fine Paid No.