Yin / Yang Theory and Its Relevance in Tai Chi Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article

International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2016) Ancient Emaki "Genesis" Exploration and Practice of Emaki Art Expression Tong Zhang Digital Media and Design Arts College Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications Beijing, China 100876 Abstract—The ancient myths and legends with distinctive generation creators such as A Gen, sheep and others, and a Chinese characteristics, refers to myths and legends from dedicated serial picture book magazine "Paint Heart", Chinese Xia Dynasty until ancient times, it carries the origin of "STORY" appears, the delicate picture and vivid story make Chinese culture and it is the foundation of the Chinese nation, it Chinese picture book also developing rapidly and has formed a influence the formation and its characteristics of the national national reading faction craze for outstanding picture books. spirit to a large extent. The study explore and practice the art expression which combines ancient culture with full visual 1) Picture book traced back to ancient Chinese Emaki: impact Emaki form, learn traditional Chinese painting China has experienced a few stages include ancient Emaki, techniques and design elements, and strive to make a perfect illustrated book in Republican period and modern picture performance for the magnificent majestic ancient myth with a books. "Picture book", although the term originated in Japan, long Emaki. It provides a fresh visual experience to the readers and promotes the Chinese traditional culture, with a certain but early traceable picture books is in China. In Heian research value. Kamakura Period Japanese brought Buddhist scriptures (Variable graph), Emaki (Lotus Sutra) and other religious Keywords—ancient myths; Emaki form; Chinese element Scriptures as picture books back to Japan, until the end of Middle Ages Emaki had developed into Nara picture books. -

Transmission of Han Pictorial Motifs Into the Western Periphery: Fuxi and Nüwa in the Wei-Jin Mural Tombs in the Hexi Corridor*8

DOI: 10.4312/as.2019.7.2.47-86 47 Transmission of Han Pictorial Motifs into the Western Periphery: Fuxi and Nüwa in the Wei-Jin Mural Tombs in the Hexi Corridor*8 ∗∗ Nataša VAMPELJ SUHADOLNIK 9 Abstract This paper examines the ways in which Fuxi and Nüwa were depicted inside the mu- ral tombs of the Wei-Jin dynasties along the Hexi Corridor as compared to their Han counterparts from the Central Plains. Pursuing typological, stylistic, and iconographic approaches, it investigates how the western periphery inherited the knowledge of the divine pair and further discusses the transition of the iconographic and stylistic design of both deities from the Han (206 BCE–220 CE) to the Wei and Western Jin dynasties (220–316). Furthermore, examining the origins of the migrants on the basis of historical records, it also attempts to discuss the possible regional connections and migration from different parts of the Chinese central territory to the western periphery. On the basis of these approaches, it reveals that the depiction of Fuxi and Nüwa in Gansu area was modelled on the Shandong regional pattern and further evolved into a unique pattern formed by an iconographic conglomeration of all attributes and other physical characteristics. Accordingly, the Shandong region style not only spread to surrounding areas in the central Chinese territory but even to the more remote border regions, where it became the model for funerary art motifs. Key Words: Fuxi, Nüwa, the sun, the moon, a try square, a pair of compasses, Han Dynasty, Wei-Jin period, Shandong, migration Prenos slikovnih motivov na zahodno periferijo: Fuxi in Nüwa v grobnicah s poslikavo iz obdobja Wei Jin na območju prehoda Hexi Izvleček Pričujoči prispevek v primerjalni perspektivi obravnava upodobitev Fuxija in Nüwe v grobnicah s poslikavo iz časa dinastij Wei in Zahodni Jin (220–316) iz province Gansu * The author acknowledges the financial support of the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) in the framework of the research core funding Asian languages and Cultures (P6-0243). -

The Symbol of the Dragon and Ways to Shape Cultural Identities in Institute Working Vietnam and Japan Paper Series

2015 - HARVARD-YENCHING THE SYMBOL OF THE DRAGON AND WAYS TO SHAPE CULTURAL IDENTITIES IN INSTITUTE WORKING VIETNAM AND JAPAN PAPER SERIES Nguyen Ngoc Tho | University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vietnam National University – Ho Chi Minh City THE SYMBOL OF THE DRAGON AND WAYS TO SHAPE 1 CULTURAL IDENTITIES IN VIETNAM AND JAPAN Nguyen Ngoc Tho University of Social Sciences and Humanities Vietnam National University – Ho Chi Minh City Abstract Vietnam, a member of the ASEAN community, and Japan have been sharing Han- Chinese cultural ideology (Confucianism, Mahayana Buddhism etc.) and pre-modern history; therefore, a great number of common values could be found among the diverse differences. As a paddy-rice agricultural state of Southeast Asia, Vietnam has localized Confucianism and absorbed it into Southeast Asian culture. Therefore, Vietnamese Confucianism has been decentralized and horizontalized after being introduced and accepted. Beside the local uniqueness of Shintoism, Japan has shared Confucianism, the Indian-originated Mahayana Buddhism and other East Asian philosophies; therefore, both Confucian and Buddhist philosophies should be wisely laid as a common channel for cultural exchange between Japan and Vietnam. This semiotic research aims to investigate and generalize the symbol of dragons in Vietnam and Japan, looking at their Confucian and Buddhist absorption and separate impacts in each culture, from which the common and different values through the symbolic significances of the dragons are obviously generalized. The comparative study of Vietnamese and Japanese dragons can be enlarged as a study of East Asian dragons and the Southeast Asian legendary naga snake/dragon in a broader sense. The current and future political, economic and cultural exchanges between Japan and Vietnam could be sped up by applying a starting point at these commonalities. -

Asian Studies (ASST) 1

Asian Studies (ASST) 1 Asian Studies (ASST) Courses ASST 0811. Asian Behavior & Thought. 3 Credit Hours. This course is an introduction to some of the major philosophical and religious traditions of Asia, and their roles in Asia and the world today. You will learn about some of the dominant features of these traditions and be exposed to several important ideas, institutions, and practices. How do these ideas influence the behavior of individuals and communities? How does individual and communal behavior and beliefs differ regionally and historically? We will read and discuss selections from primary works as well as secondary scholarship, while surveying key doctrines and historical developments. Note: This course fulfills the Human Behavior (GB) requirement for students under GenEd and Individual & Society (IN) for students under Core. Students cannot receive credit for this course if they have successfully completed any of the following: CRIT 0811, PHIL 0811, CHI 0811, JPNS 0811, REL 0811, or REL 0911. Course Attributes: GB Repeatability: This course may not be repeated for additional credits. ASST 0815. Language in Society. 3 Credit Hours. How did language come about? How many languages are there in the world? How do people co-exist in countries where there are two or more languages? How do babies develop language? Should all immigrants take a language test when applying for citizenship? Should English become an official language of the United States? In this course we will address these and many other questions, taking linguistic facts as a point of departure and considering their implications for our society. Through discussions and hands-on projects, students will learn how to collect, analyze, and interpret language data and how to make informed decisions about language and education policies as voters and community members. -

Hmong Religion

Hmong Religion N ic h o l a s T a p p The Chinese University of Hong Kong I. THE OTHERWORLD I ntroduction The Hmong are pantheists, believing in a variety of natural and super natural spiritual forces living in and animating all things. The Hmong world is inhabited by a variety of natural, ancestral, and supernatural spirits or gods. As with much in Hmong religion, Chinese influence is strong, and the Hmong Otherworld is closely modelled on the Chinese Otherworld, which in turn represents an inversion of the classical Chi nese bureacracy. The Hmong world of yeeb ceeb parallels the Chinese world of y in , the dark world 01 the spirits: the Hmong world of y a j ceeb parallels the Chinese world of yang, the bright world of men and women, of material objects and nature. In previous times, the Hmong often say, men and spirits could meet and talk to each other, and the passage between the two worlds was much easier. Now that the two worlds have become divided, only the shaman may, with impunity, venture into the Otherworld and return safely to this one. S p ir it u a l B e in g s In the Hmong song of Creation which is sung during the funeral rites, it is told how it was the frog, Nplooj Lwg, who first created the world of men and spirits. However, he was killed by the first humans, in a rage because he had lied to them about the size of the world (he had said it was no larger than the palm of a hand, the sole of a foot).1 The frog’s dying curse was that henceforth mankind would know sickness and death, the leaves would fall from the trees and the forests grow thinner. -

Myths of the Yellow Emperor

6 Myths of the Yellow Emperor T h e god called the Yellow Emperor played a minor role in the early tradition, but he gradually acquired a complex biography, an elab orate genealogy, and a cycle o f folkloristic legends that gave him an exalted status in the divine pantheon. Although later tradition made the Yellow Emperor the supreme deity of the Taoist pantheon, when philo sophical Taoism had acquired a more religious coloration and was espoused by imperial rulers, and although traditional histories have presented this god as the pacific culture bearer, the early tradition clearly shows that the Yellow Emperor (Huang Ti) is first and foremost a warrior-god who successfully fought against a series o f enemies — the Flame Emperor, Ch’ih Yu the god o f war, the Four Emperors, the hero Hsing T ’ien, and the one-legged god K ’uei, besides many other lesser known mythical figures. When the warrior function of the Yellow Emperor is compared with gods in mythology worldwide, his battles are violent but not frenzied, purposeful but not mindless, pacific in motive but not anarchic in the way that Thorr, Indra, and Odin are in their warrior function. In addition to his functions as warrior and peacemaker, this god also had the function o f culture bearer in later local traditions. For the Han historian Ssu-ma Ch’ien, the Yellow Em peror symbolized the fountainhead of Chinese culture and civilization. 130 Myths o f the Yellow Emperor — 131 The Battle between the Yellow Emperor and the Flame Emperor The first two readings, from the early and later tradition, narrate the battle between the Yellow Emperor and his brother, the Flame Em peror, Yen Ti. -

Handbook of Chinese Mythology TITLES in ABC-CLIO’S Handbooks of World Mythology

Handbook of Chinese Mythology TITLES IN ABC-CLIO’s Handbooks of World Mythology Handbook of Arab Mythology, Hasan El-Shamy Handbook of Celtic Mythology, Joseph Falaky Nagy Handbook of Classical Mythology, William Hansen Handbook of Egyptian Mythology, Geraldine Pinch Handbook of Hindu Mythology, George Williams Handbook of Inca Mythology, Catherine Allen Handbook of Japanese Mythology, Michael Ashkenazi Handbook of Native American Mythology, Dawn Bastian and Judy Mitchell Handbook of Norse Mythology, John Lindow Handbook of Polynesian Mythology, Robert D. Craig HANDBOOKS OF WORLD MYTHOLOGY Handbook of Chinese Mythology Lihui Yang and Deming An, with Jessica Anderson Turner Santa Barbara, California • Denver, Colorado • Oxford, England Copyright © 2005 by Lihui Yang and Deming An All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yang, Lihui. Handbook of Chinese mythology / Lihui Yang and Deming An, with Jessica Anderson Turner. p. cm. — (World mythology) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57607-806-X (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 1-57607-807-8 (eBook) 1. Mythology, Chinese—Handbooks, Manuals, etc. I. An, Deming. II. Title. III. Series. BL1825.Y355 2005 299.5’1113—dc22 2005013851 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116–1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Noah's Ark Hidden in the Ancient Chinese Characters

Papers Noah’s Ark hidden in the ancient Chinese characters — Voo, Sheeley & Hovee from chapters six to nine.4 The Chinese also have a similar Noah’s Ark story. Notably, a great flood that occurred as a result of the rebellion of a group of people during the legendary period hidden in the (about 2500 BC). In the text of Huai Nan Zi (南子, written in 200 BC),5 legend states that in ancient times, the poles (north, south, east and west) that supported the roof of the ancient Chinese world were broken. As a result, the heavens were broken and the nine states of China experienced continental shift characters and split. Fire broke out and the water from the heavens could not be stopped, causing a flood. Shu Jing (書經, writ- Kui Shin Voo, Rich Sheeley and Larry ten 1000 BC) relates how there was grieving and mourning Hovee all over the earth, and also describes the extent of the flood; how the water reached the sky, and flooded the mountains Legends from ancient China describe a global cata- and drowned all living things. In the midst of this global strophic flood so vast that the waters reached the calamity, a hero by the name of ‘Nüwa’ (女媧) appeared sun and covered the mountains, drowning all the and sealed the flood holes with colourful stones and repaired land-dwelling creatures, including mankind. In the the broken poles using four turtle legs. Nüwa used earth to midst of this global calamity, there stood a legend- create humans to replenish mankind after the flood (Feng ary hero named Nüwa (女媧) who turned back the Su Tong Yi, 風俗通義).6,7 Although the name Nüwa (女 flood and helped to repopulate the world. -

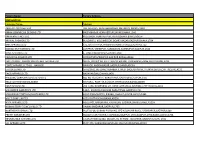

Factory Name

Factory Name Factory Address BANGLADESH Company Name Address AKH ECO APPARELS LTD 495, BALITHA, SHAH BELISHWER, DHAMRAI, DHAKA-1800 AMAN GRAPHICS & DESIGNS LTD NAZIMNAGAR HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,1340 AMAN KNITTINGS LTD KULASHUR, HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH ARRIVAL FASHION LTD BUILDING 1, KOLOMESSOR, BOARD BAZAR,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,1704 BHIS APPARELS LTD 671, DATTA PARA, HOSSAIN MARKET,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1712 BONIAN KNIT FASHION LTD LATIFPUR, SHREEPUR, SARDAGONI,KASHIMPUR,GAZIPUR,1346 BOVS APPARELS LTD BORKAN,1, JAMUR MONIPURMUCHIPARA,DHAKA,1340 HOTAPARA, MIRZAPUR UNION, PS : CASSIOPEA FASHION LTD JOYDEVPUR,MIRZAPUR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH CHITTAGONG FASHION SPECIALISED TEXTILES LTD NO 26, ROAD # 04, CHITTAGONG EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE,CHITTAGONG,4223 CORTZ APPARELS LTD (1) - NAWJOR NAWJOR, KADDA BAZAR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH ETTADE JEANS LTD A-127-131,135-138,142-145,B-501-503,1670/2091, BUILDING NUMBER 3, WEST BSCIC SHOLASHAHAR, HOSIERY IND. ATURAR ESTATE, DEPOT,CHITTAGONG,4211 SHASAN,FATULLAH, FAKIR APPARELS LTD NARAYANGANJ,DHAKA,1400 HAESONG CORPORATION LTD. UNIT-2 NO, NO HIZAL HATI, BAROI PARA, KALIAKOIR,GAZIPUR,1705 HELA CLOTHING BANGLADESH SECTOR:1, PLOT: 53,54,66,67,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH KDS FASHION LTD 253 / 254, NASIRABAD I/A, AMIN JUTE MILLS, BAYEZID, CHITTAGONG,4211 MAJUMDER GARMENTS LTD. 113/1, MUDAFA PASCHIM PARA,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1711 MILLENNIUM TEXTILES (SOUTHERN) LTD PLOTBARA #RANGAMATIA, 29-32, SECTOR ZIRABO, # 3, EXPORT ASHULIA,SAVAR,DHAKA,1341 PROCESSING ZONE, CHITTAGONG- MULTI SHAF LIMITED 4223,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH NAFA APPARELS LTD HIJOLHATI, -

Religion and Nationalism in Chinese Societies

RELIGION AND SOCIETY IN ASIA Kuo (ed.) Kuo Religion and Nationalism in Chinese Societies Edited by Cheng-tian Kuo Religion and Nationalism in Chinese Societies Religion and Nationalism in Chinese Societies Religion and Society in Asia The Religion and Society in Asia series presents state-of-the-art cross-disciplinary academic research on colonial, postcolonial and contemporary entanglements between the socio-political and the religious, including the politics of religion, throughout Asian societies. It thus explores how tenets of faith, ritual practices and religious authorities directly and indirectly impact on local moral geographies, identity politics, political parties, civil society organizations, economic interests, and the law. It brings into view how tenets of faith, ritual practices and religious authorities are in turn configured according to socio-political, economic as well as security interests. The series provides brand new comparative material on how notions of self and other as well as justice and the commonweal have been predicated upon ‘the religious’ in Asia since the colonial/imperialist period until today. Series Editors Martin Ramstedt, Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle Stefania Travagnin, University of Groningen Religion and Nationalism in Chinese Societies Edited by Cheng-tian Kuo Amsterdam University Press This book is sponsored by the 2017 Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange (Taiwan; SP002-D-16) and co-sponsored by the International Institute of Asian Studies (the Netherlands). Cover illustration: Chairman Mao Memorial Hall in Beijing © Cheng-tian Kuo Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Typesetting: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. -

The Legendary Emperors

Indiana University, History G380 – class text readings – Spring 2010 – R. Eno 1.3 THE LEGENDARY EMPERORS During the Classical era, the patrician elite was highly concerned with learning about the past and understanding the lessons it taught. In some cases, the effort was a sincere attempt to become enlightened; in other cases, the search for the past was actually a search for more practical tools, such as justifications for contemporary political goals. It is unclear to us just how much material was actually available for constructing an account of the distant past. What is clear is that the narratives of China’s earliest history were cobbled together out of a mix of outright myths, legends with some historical basis, and the political and ethical prejudices of their authors. It is easiest to conceive of the narrative of the past as being constructed backwards from the early Zhou. The Zhou people knew that before them had come a series of rulers belonging to a single ruling house, the Shang Dynasty. A clear picture existed for only a few Shang kings, but the Shang founder, at least, was seen as an heroic man, quite similar in many ways to the Zhou founders. Prior to the Shang, it was believed that there had been a dynasty called the Xia. Although these kings were mostly indistinguishable, again, the founding king, a man known as the Emperor Yu, was clearly conceived. Yu represents a transitional figure. Prior to Yu, history was seen as a succession of emperors, mostly sages, rather than as a succession of dynasties. -

Fabled Flora and Fauna

14 Fabled Flora and Fauna IV lyth ic nature manifests itself as a god-haunted world under the sway of supernatural beings. Nature is subordinated to the gods, who are immanent in sacred mountains, streams, rocks, and trees. Nature reveals the potency o f the gods; they are elemental, controlling light, heat, wind, and rain; they are generative, producing irrigated fields, fer tile soil, and abundant crops. And the gods can be jealous and punitive, withholding life and creative energy. Humans are in and o f nature, and the gods belong to the world o f nature and o f humans. The two spheres o f the human and the divine interact in terms o f form and function. When the gods manifest themselves, they appear as half-human, half animal beings, or as hybrid creatures. Nii Kua and Fu Hsi took on half human, half-serpentine form. Many deities are described as having a bird’s body and a human face. And the metamorphoses o f gods and demigods demonstrate the easy transference from one state to another. The epitome o f this interaction is the myth o f the dying god P’an Ku. This interconnectedness between the gods, nature, and humans has a negative and a positive dimension. Its negative dimension is visible in its congeries o f hybrid monsters and beasts such as Hsiang Liu or the Wu-chih-ch’i, who wreak havoc on the human world. Conversely, the concept o f perfect harmony among the three worlds is visible in the earthly paradises o f K’un-lun or the Isles o f the Immortals in the east 230 Fabled Flora and Fauna — 231 ern sea.