Decentralization and Implementation of Climate Change Policy in Uganda Esbern Friis-Hansen, Bernard Bashaasha and Charles Aben

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from the Internet and Distributed Inflammatory Speeches and Images Including Beheadings Carried out by Iraqi Insurgents

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH WORLD REPORT 2006 EVENTS OF 2005 Copyright © 2006 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Co-published by Human Rights Watch and Seven Stories Press Printed in the United States of America ISBN-10: 1-58322-715-6 · ISBN-13: 978-1-58322-715-2 Front cover photo: Oiparcha Mirzamatova and her daughter-in-law hold photographs of family members imprisoned on religion-related charges. Fergana Valley, Uzbekistan. © 2003 Jason Eskenazi Back cover photo: A child soldier rides back to his base in Ituri Province, northeastern Congo. © 2003 Marcus Bleasdale Cover design by Rafael Jiménez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] Rue Van Campenhout 15, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 732 2009, Fax: +32 2 732 0471 [email protected] 9 rue Cornavin 1201 Geneva Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] Markgrafenstrasse 15 D-10969 Berlin, Germany Tel.:+49 30 259 3060, Fax: +49 30 259 30629 [email protected] www.hrw.org Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. -

“Disco Dreads”

“Disco Dreads” Self-fashioning through Consumption in Uganda’s Hip Hop Scene Image-making, Branding and Belonging in Fragile Sites Simran Singh Department of Music, Royal Holloway, University of London Dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Declaration of authorship ……………………………………………………………….5 Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………….6 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………8 List of figures…………………………………………………………………………….7 Chapter 1 Introduction to thesis “The chick with the kicks” ………………………………………………………………9 Self-fashioning through consumption: theoretical frames………………………………21 Thesis outline……………………………………………………………………………38 Chapter 2 Music in Uganda Patronage to persecution: a brief overview of Uganda’s music…………………………42 Global influences, the birth of a music industry and an FM revolution: 1986 onwards………………………………………………………………………… …45 Imagining the popular: 1950s – 1980s…………………………………………………...51 Investigating the traditional……………………………………...………………………57 Music as message in the 21st century…………………………...………………………..61 Chapter 3 Method A Porsche’s place………………………………………………………………………..69 Friendship and the Field………………………………………………………………....73 The epistemic community……………………………………………………………….76 Ethnographic phenomenology…………………………………………………………..78 2 Web 2.0 or social networking………………………………………………………………81 Visualising hip hop…………………………………………………………………………83 Practical tools and concerns in the field……………………………………………………87 Chapter 4 Image-making and the Ugandan hip hop ‘mogul’ The mogul’s visual density…………………………………………………………………..90 -

The Case for Kiswahili As a Regional Broadcasting Language in East Africa

The Case for Kiswahili as a Regional Broadcasting Language in East Africa by Vincent Kawoya [email protected] Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya & J.S. Makokha [email protected] Institut fur Englische Philologie, Freie Universitat Berlin, Germany. Abstract The peoples of East Africa have a long history of a rich and diverse regional heritage. Perhaps one of the most renowned aspects of this heritage is Kiswahili, the language widely spoken and understood across Eastern Africa. As the numbers of people who are proficient in the language continue to grow year after year, there have been numerous enriching perspectives on the anthropological, historical, literary and sociolinguistic aspects of Kiswahili. In this article, we offer a fresh perspective on how Kiswahili can be tapped as a resource for mobilizing popular support for the East African regional integration process across the five member-states of the current East African Community: Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi. Kiswahili should be elevated to the position of a regional broadcasting language for a proposed regional broadcasting network operating under the aegis of the East African Community in Arusha, Tanzania. This is the main argument of the article. The argument is grounded on three main points, namely, media studies indicate that ICT and FM radio stations have become very popular mass media across Africa in the past two decades; radios are ubiquitous media of communication, entertainment and education across East Africa, especially in the rural areas where the vast majority of the people still live; and a regional broadcasting service, using the popular FM mode, can be mooted by the EAC Secretariat in Arusha to promote the programs of the EAC and harness the popular support for its intentions. -

Social Sciences

KIU Journal of Social Sciences College of Humanities and Social Sciences Kampala International University, Uganda. 1 Copyright © 2016 College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Kampala International University. All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of research or private study, or criticism or review, and only as permitted under the Copyright Act, this publication may only be produced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with prior written permission of the Copyright Holder. Published in March, 2016 ISSN: 1996-9023 Published by: College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Kampala International University, Kampala, Uganda. 2 KIU Journal of Social Sciences Copyright©2016 Kampala International University ISSN: 1996902-3; 2(1): 1–2 Editorial This issue of KIU Journal of Social Sciences touches on governance, development, organizational management, social psychology and creative writing. In Governance and Development, Tarabinah discusses the impact of activities of Transnational Oil Corporations, especially Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC) on human rights in Bayelsa state, Nigeria. He advises the Federal Government of Nigeria to establish an effective system of oversight in the oil industry which will factor the externality of oil on social and human rights. Sapele also argues that since NEPAD has not created the desirable changes on the individuals, participating countries should implement the policies and programmes of NEPAD, coordinate and complete poverty projects identified in the poverty -

Turning Conflict Into Coexistence: Cross-Cutting Ties and Institutions in the Agro-Pastoral Borderlands of Lake Naivasha Basin, Kenya

Turning conflict into coexistence: cross-cutting ties and institutions in the agro-pastoral borderlands of Lake Naivasha basin, Kenya Inaugural dissertation to complete the doctorate from the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne in the subject, Social and Cultural Anthropology presented by Eric Mutisya Kioko born on 03.05.1983 in Machakos, Kenya Cologne, November 2016 Abstract The Maasai/Kikuyu agro-pastoral borderlands of Maiella and Enoosupukia, located in the hinterlands of Lake Naivasha’s agro-industrial hub, are particularly notorious in the history of ethnicised violence in the Kenya’s Rift Valley. In October 1993, an organised assault perpetrated by hundreds of Maasai vigilantes, with the assistance of game wardens and administration police, killed more than 20 farmers of Kikuyu descent. Consequently, thousands of migrant farmers were violently evicted from Enoosupukia at the instigation of leading local politicians. Nowadays, however, intercommunity relations are surprisingly peaceful and the cooperative use of natural resources is the rule rather than the exception. There seems to be a form of reorganization. Violence seems to be contained and the local economy has since recovered. This does not mean that there is no conflict, but people seem to have the facility to solve them peacefully. How did formerly violent conflicts develop into peaceful relations? How did competition turn into cooperation, facilitating changing land use? This dissertation explores the value of cross-cutting ties and local institutions in peaceful relationships and the non-violent resolution of conflicts across previously violently contested community boundaries. It mainly relies on ethnographic data collected between 2014 and 2015. -

A Review of Key Themes and Issues Emerging from Literature on Hiv/Aids and Higher Education in Africa and Uganda in Particular

A REVIEW OF KEY THEMES AND ISSUES EMERGING FROM LITERATURE ON HIV/AIDS AND HIGHER EDUCATION IN AFRICA AND UGANDA IN PARTICULAR A Review Commissioned by International Institute for Educational Planning UNESCO Paris Anne Ruhweza Katahoire (Ph D) MAKERERE UNIVERSITY Department of Adult Education and Communication Studies October 2004 1 Abbreviations and Acronyms AAAS –American Association for the Advancement of Science AAI-African American Institute AAU- Association of African Universities ACU – Association of Commonwealth Universities ADEA - Association for the Development of Education in Africa ART – Anti Retroviral Therapy AWSE – African Women in Science and Engineering BOMAID – Botswana Medical Aid Society CDC- Centre for Disease Control HIV/AIDS –Human Immunodeficiency Virus/ Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome KIST- Kigali Institute for Technology MEDUNSA- University of the Witwatersrand, Medical University of Southern Africa MFMC – My Future is My Choice MoES- Ministry of Education and Sports MRC- Medical Research Council MUCAP- Makerere University Community Awareness Project MUPEC- Maseno University’s Peer Education Club NORAD- Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation RAU- Rand Afrikaans University SAUVCA – South African Universities Vice-Chancellors Association TASO- The AIDS Support Organization UAC – Uganda AIDS Commission UNAIDS – The joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS UNESCO- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization UNITRA- University of Transkei UNISA- University of South Africa UWC – University -

Sexual Behavioural Change for HIV Where Have Theories Taken

Sexual behavioural change for HIV: Where have theories taken us? Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS UNICEF • UNDP • UNFPA • UNDCP UNESCO • WHO • WORLD BANK The text was written by Rachel King UNAIDS/99.27E (English original, June 1999) © Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) The designations employed and the presentation of the 1999. All rights reserved. This document, which is not a for- material in this work do not imply the expression of any mal publication of UNAIDS may be freely reviewed, quoted, opinion whatsoever on the part of UNAIDS concerning the reproduced or translated, in part or in full, provided the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its source is acknowledged. The document may not be sold or authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers used in conjunction with commercial purposes without and boundaries. prior written approval from UNAIDS (Contact: UNAIDS Information Centre). UNAIDS – 20 avenue Appia – 1211 Geneva 27 – Switzerland Tel.: (+41 22) 791 46 51 – Fax : (+41 22) 791 41 65 e-mail: [email protected] – http://www.unaids.org Sexual behavioural change for HIV: Where have theories taken us? Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS UNICEF • UNDP • UNFPA • UNDCP UNESCO • WHO • WORLD BANK UNAIDS Geneva, Switzerland 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations........................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction............................................................................................................................. -

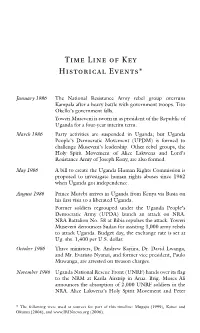

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006). -

The Case of East Africa

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT AND UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME MAINSTREAMING GENDER INTO TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT STRATEGIES: THE CASE OF EAST AFRICA TRADE NEGOTIATIONS AND AFRICA SERIES: No. 5 UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2008 Note • This report was prepared by Jacqueline Maleko, Ministry of Industry, Trade and Marketing, United Republic of Tanzania, within the framework of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)- financed project on Trade Capacity Development for Africa and the Joint (International Trade Centre (ITC)/UNCTAD/World Trade Organization (WTO)) Integrated Technical Assistance Programme (JITAP) to Selected Least Developed and Other African Countries. • The symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. • The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. • Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a reference to the document number. A copy -

Competition Policy Digital Financial Inclusion and Digital Identity on the Development Agenda

Competition Policy in the Digital Age - Case Studies from Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa in the Digital Age Policy Competition COMPETITION POLICY DIGITAL AGE Case Studies from Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa 2016 Competition Policy in the Digital Age: 2 Case Studies from Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa About the GSMA The GSMA represents the interests of mobile operators worldwide, uniting nearly 800 operators with almost 300 companies in the broader mobile ecosystem, including handset and device makers, software companies, equipment providers and internet companies, as well as organisations in adjacent industry sectors. The GSMA also produces industry-leading events such as Mobile World Congress, Mobile World Congress Shanghai and the Mobile 360 Series conferences. For more information, please visit the GSMA corporate website at www.gsma.com Follow the GSMA on Twitter: @GSMA Competition Policy in the Digital Age: Case Studies from Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa 3 Last visited page, press: Competition Policy in the Digital Age: 2 Case Studies from Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa Alt About this booklet This booklet is for you if you have an interest in competition policy in the digital communications sector. There are chapters on Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, so this booklet is for you specifically, if you are considering aspects of competition law and regulation in these regions. You are: • A lawmaker. There is a need to consider the balance between sectoral regulation and competition law. The evidence presented in this booklet points overwhelmingly to the benefits (for the economy as a whole) brought about by enactment of a modern competition law, properly enforced by a well-resourced competition authority. -

Uganda, Country Information

Uganda, Country Information UGANDA ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURE HUMAN RIGHTS HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR EVENTS POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS PROMINENT PEOPLE GLOSSARY REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF THE DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended for use by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Uganda.htm[10/21/2014 10:09:59 AM] Uganda, Country Information 2. -

NOTE the Buwambo Kaolin Deposit in Central Uganda: Mineralogical And

Geochemical Journal, Vol. 35, pp. 245 to 256, 2001 NOTE The Buwambo kaolin deposit in central Uganda: Mineralogical and chemical composition GEORGE W. A. NYAKAIRU,1 CHRISTIAN KOEBERL1* and HANS KURZWEIL2 1Institute of Geochemistry, University of Vienna, Althanstrasse 14, A-1090 Vienna, Austria 2Institute of Petrology, University of Vienna, Althanstrasse 14, A-1090 Vienna, Austria (Received February 12, 2001; Accepted June 20, 2001) Kaolin from the Buwambo deposit, located about 27 km north of Kampala (Uganda), has been analyzed for its mineralogical and chemical composition. The kaolin is derived from granite of the basement, which is exposed due to deeply weathered Buganda-Toro cover rocks. Kaolinite is the dominant mineral, with quartz and muscovite/illite as accessory minerals. Chemical data show that the kaolin is composed mainly of SiO2 and Al2O3, with the other oxides being present in trace amounts. The depletion in Ti, Fe, Mn, Mg, Ca, Na, and K not only shows the extent of the kaolinization, but also gives Buwambo kaolin its almost white color. The kaolinization and weathering processes have enriched Ni and depleted other trace ele- ment contents in the Buwambo kaolin. The chondrite-normalized rare earth element (REE) patterns show enrichment in the light REEs, with a negative Ce anomaly. The REE pattern and the content of the other trace elements, show evidence of alteration and weathering processes related to kaolinization. The minera- logical and chemical compositions indicate that the kaolin is suitable for industrial use. its occur, their industrial use is restricted to manu- INTRODUCTION facturing of bricks and pottery (Nyakairu and In the last decade, the kaolin industry has en- Kaahwa, 1998, and references therein).