Download the Adobe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Swinging Trapeze 1000-01 2:30-3:30PM Swinging Trapeze 1000-02 2:00-3:00PM Hammock 0200-02 3:00-3:30PM Swinging Trapeze 1000-02 2:45-3:30PM Swinging Trapeze 1000-01 2:15-3:15PM 9:00 AM Wings 0000-01 2:30-3:45PM Cloud Swing 1000-01 2:30-3:00PM Revolving Ladder 1000-01 3:15-4:00PM Double Trapeze 0100-04 3:30-4:15PM Duo Trapeze 0100-01 3:15-4:00PM Flying Trapeze 0000-02 3:00 PM 3:00 Mexican Cloud Swing 0100-02 3:30-4:15PM Pas de Deux 0000-01 3:00-4:00PM Swinging Trapeze 0100-02 3:15-4:00PM Handstands 1000-01 3:30-4:15PM Duo Trapeze 0100-03 3:15-4:00PM Globes 0000-01 Swinging Trapeze 0100-01 3:30-4:15PM Double Trapeze 0100-02 3:15-4:00PM Triangle Trapeze 1000-01 3:30-4:15PM Chair Stacking 1000-01 Triangle Trapeze 0100-02 3:15-4:00PM Low Casting Fun 0000-04 4-Girl Spinning Cube 1000-01 3:45-4:30PM Duo Trapeze 0100-02 3:30-4:15PM Static Trapeze 1000-01 4-Girl Spinning Cube 0000-01 3:30-4:00PM Mini Hammock 0000-02 Handstands 1000-01 Manipulation Cube 0000-01 3:30-4:00PM Star 0100-01 High Wire 1000-01 Stilt Walking 1000-01 3:30-4:25PM Toddlers 0200-03 ages 3-4 Mexican Cloud Swing 0100-02 3:30-4:15PM Acrobatics 0205-01 ages 10+ Triangle Trapeze 1000-01 3:30-4:15PM Double Trapeze 0100-04 3:30-4:15PM Stilt Walking 1000-01 3:30-4:25PM Trampoline 0000-04 ages 6-9 Swinging Trapeze 0100-01 3:30-4:15PM Bungee Trapeze 0300-01 Cloud Swing 0100-02 4:00-4:30PM Handstands 1000-01 3:30-4:15PM Duo Hoops 1000-01 4:00-4:30PM 4:00 PM 4:00 4-Girl Spinning Cube 1000-01 3:45-4:30PM Circus Spectacle 0100-01 Pas de Deux -

8 Places to Run Away with the Circus

chicagoparent.com http://www.chicagoparent.com/magazines/going-places/2016-spring/circus 8 places to run away with the circus The Actors Gymnasium Run away with the circus without leaving Chicago! If your child prefers to hang upside down while swinging from the monkey bars or tries to jump off a kitchen cabinet to reach the kitchen fan, he belongs in the circus. He’ll be able to squeeze out every last ounce of that energy, and it’s the one place where jumping, swinging, swirling and balancing on one foot is encouraged. Here are some fabulous places where your child can juggle, balance and hang upside down. MSA & Circus Arts 1934 N. Campbell Ave., Chicago; (773) 687-8840 Ages: 3 and up What it offers: Learn skills such as juggling, clowning, rolling globe, sports acrobatics, trampoline, stilts, unicycle 1/4 and stage presentation. The founder of the circus arts program, Nourbol Meirmanov, is a graduate of the Moscow State Circus school, and has recruited trained circus performers and teachers to work here. Price starts: $210 for an eight-week class. The Actors Gymnasium 927 Noyes St., Evanston; (847) 328-2795 Ages: 3 through adult (their oldest student at the moment is 76) What it offers: Kids can try everything from gymnastics-based circus classes to the real thing: stilt walking, juggling, trapeze, Spanish web, lyra, contortion and silk knot. Classes are taught by teachers who graduated from theater, musical theater and circus schools. They also offer programs for kids with disabilities and special needs. Price starts: $165 for an 8-10 week class. -

Challenging Artists to Create Tomorrow's Circus Circadium Is the Only Higher-Education Program for Circus Artists in the United States

Challenging Artists to Create Tomorrow's Circus Circadium is the only higher-education program for circus artists in the United States. We offer a full-time, three-year course that grants a Diploma of Circus Arts, recognized by the Pennsylvania Board of Education. We are committed to radically changing the future of circus, and performing arts as a whole, by bringing a multidisci- plinary and experiment-driven approach to creation and performance. As a 501(c)3 organization, the school relies on individual contributions and foundation support to cover costs that cannot be offset by student tuition. We keep our tuition rates low to encourage students from different backgrounds to attend, and to ensure that they will not launch their artistic careers bur- dened by student debt. Circus Arts are Thriving Worldwide, contemporary representations of circus are thriving and expanding – from Cirque du Soleil, to Pink’s performance at the Grammys, to the wide array of theatre and dance groups that incorporate elements of acrobatics, aerials, and clowning into their performances. Circus is no longer confined to the Big Top, as artists in every discipline discover its rich potential for physical expression. And yet, until now the United States lacked a dedicated facility for training contemporary circus artists. Students who wanted to train intensively in circus traveled to Canada, Europe, or Australia. They often stayed in those countries and established companies, meaning that now virtually all of the edgy, exciting, vibrant new circus companies are based overseas. There are a growing number of arts presenters in the U.S. who are clamoring for these kinds of shows – and the only way to get them has been to import them. -

Florida State University Flying High Circus

Florida State University Flying High Circus There has been an FSU Flying High Circus for almost as long as there has been a Florida State University. When the Florida State College for Women went coeducational in 1947, one of the new faculty members was Jack Haskin. As a high school coach in Pontiac, Illinois, Haskin had staged student gymnastic exhibitions. He wanted to start an activity at the new university which would allow men and women to participate together. His idea was the circus. The Flying High Circus is a self-supporting activity. No student activity fees, tuition payments, university or state funds go towards circus activities. Unlike many other athletic endeavors, the students receive no tuition waivers or university scholarships for their long hours of practice for the nationally famous shows that bring credit to FSU. The acts in the Flying High Circus have evolved from "circus activity" to "circus professionalism.” Performances are often of such high caliber that professional contracts are sometimes offered to student performers, especially on the flying trapeze. In the circus, you will see tricks attempted and completed that are more difficult than many you would see in other American or European circuses. Examples include the triple somersault on the flying trapeze (accomplished by two performers at FSU), the seven man pyramid on the high wire (which has only been performed by two other groups), double back somersaults on the skypole and many more. Some acts are unique to the FSU Circus or are rarely done elsewhere such as triple aerial high casting and three-lane breakaway. -

Circus Report, May 24, 1976, Vol. 5, No. 21

M« Miiiifi eiiHS fllljj 5th Year Ma> 2k, 1976 Number 21 Show Folds in Texas An anticipated circus day at San Antonio (Texas) turned out to be a disappointment for fans and show folks alike. In the midst of a steady rain Circus Galaxy folded in that .city on May 9th. Early this year announcements about the circus indicated it would rival the best shows on the road. Phone crews started their San Antonio promotion about two months ago. While they were vague about the show's name they were positive it was a "large tented show" with the best of everything. CFA's who saw the circus at Victoria described it as "a small show" with no show owned equipment. They called it strictly "a drum and organ show" with the Oscarian Family and some Mexican performers. Six performances were scheduled for San Antonio, but prior to the first show, performers were told they (Continued on Page 16) A VAILABLE fOP LIMITED ENGAGEMENTS HOLLYWOOD ELEPHANTS Contact JUDY JACOBSKAYE Suit* 519 • 1680 North Vine Street • Hollywood, California • 90028 Area Code 213 • 462-6001 Page 2 The Circus Report American Continental by MIKE SPORRER The 1976 circus season got off to a big start with the arriv- al of the American Continental Circus at Seattle, Wash. The May 1-5 engagement was sponsored by the Police Officers Guild, that organi- zation's llth annual circus presentation. This year's Bicentennial edition is a colorful one and is well presented. The center ring is new and all three are painted red, white and blue. -

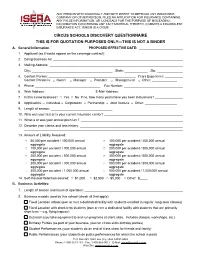

Circus Schools Discovery Questionnaire This Is for Quotation Purposes Only—This Is Not a Binder A

ANY PERSON WHO KNOWINGLY AND WITH INTENT TO DEFRAUD ANY INSURANCE COMPANY OR OTHER PERSON, FILES AN APPLICATION FOR INSURANCE CONTAINING ANY FALSE INFORMATION, OR CONCEALS FOR THE PURPOSE OF MISLEADING, INFORMATION CONCERNING ANY FACT MATERIAL THERETO, COMMITS A FRAUDULENT INSURANCE ACT, WHICH IS A CRIME. CIRCUS SCHOOLS DISCOVERY QUESTIONNAIRE THIS IS FOR QUOTATION PURPOSES ONLY—THIS IS NOT A BINDER A. General Information PROPOSED EFFECTIVE DATE: 1. Applicant (as it would appear on the coverage contract): 2. Doing Business As: 3. Mailing Address: City: State: Zip: 4. Contact Person: Years Experience: Contact Person is: □ Owner □ Manager □ Promoter □ Management □ Other: 5. Phone: Fax Number: 6. Web Address: E-Mail Address: 7. Is this a new business? □ Yes □ No If no, how many years have you been in business? 8. Applicant is: □ Individual □ Corporation □ Partnership □ Joint Venture □ Other: 9. Length of season: 10. Who was your last or is your current insurance carrier? 11. What is or was your annual premium? 12. Describe your claims and loss history: 13. Amount of Liability Required: □ 50,000 per accident / 100,000 annual □ 100,000 per accident / 200,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 100,000 per accident / 300,000 annual □ 200,000 per accident / 300,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 200,000 per accident / 500,000 annual □ 300,000 per accident / 500,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 300,000 per accident / 300,000 annual □ 500,000 per accident / 500,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 300,000 per accident / 1,000,000 annual □ 500,000 per accident / 1,000,000 annual aggregate aggregate 14. Self-Insured Retention desired: □ $1,000 □ $2,500 □ $5,000 □ Other: $ B. -

Acrobatics Acts, Continued

Spring Circus Session Juventas Guide 2019 A nonprofit, 501(c)3 performing arts circus school for youth dedicated to inspiring artistry and self-confidence through a multicultural circus arts experience www.circusjuventas.org Current Announcements Upcoming Visiting Artists This February, we have THREE visiting artists coming to the big top. During the week of February 4, hip hop dancer and choreographer Bosco will be returning for the second year to choreograph the Teeterboard 0200 spring show performance along with a fun scene for this summer's upcoming production. Also arriving that week will be flying trapeze expert Rob Dawson, who will attend all flying trapeze classes along with holding workshops the following week. Finally, during our session break in February, ESAC Brussels instructor Roman Fedin will be here running Hoops, Mexican Cloud Swing, Silks, Static, Swinging Trapeze, Triple Trapeze, and Spanish Web workshops for our intermediate-advanced level students. Read more about these visiting artists below: BOSCO Bosco is an internationally renowned hip hop dancer, instructor, and choreographer with over fifteen years of experience in the performance industry. His credits include P!nk, Missy Elliott, Chris Brown, 50 Cent, So You Think You Can Dance, The Voice, American Idol, Shake It Up, and the MTV Movie Awards. Through Bosco Dance Tour, he’s had the privilege of teaching at over 170 wonderful schools & studios. In addition to dance, he is constantly creating new items for BDT Clothing, and he loves honing his photo & video skills through Look Fly Productions. Bosco choreographed scenes in STEAM and is returning for his 2nd year choreographing spring and summer show scenes! ROB DAWSON As an aerial choreographer, acrobatic equipment designer, and renowned rigger, Rob Dawson has worked with entertainment companies such as Cirque du Soleil, Universal Studios, and Sea World. -

(SARS-Cov-2) Safety Protocols Is to Provide an En

TSNY DC CORONAVIRUS PHASE 2 SAFETY PROTOCOLS The goal of TSNY’s coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) safety protocols is to provide an environment that is as safe as possible for both students and staff during Phase 2 of Washington, D.C.’s phased re-opening. Safety will depend on equipment and personal sanitization procedures, social distancing, controlled behavior patterns, utilization of natural factors that reduce risk, and testing. These protocols are designed to minimize risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, however given the nature of what we do, we recognize that this risk cannot be eliminated entirely. Any staff or students who are not comfortable with the protocols and procedures outlined below may elect not to return to work/participate in the session without penalty. In addition, we recognize that due to pre-existing conditions or other obstacles, not all students will be able to adhere to these regulations. In the name of public safety, we cannot make exceptions to our policies. While TSNY is always committed to providing an individualized circus experience to all participants, current procedures related to social distancing and mask wearing will impact our ability to make certain accommodations in our sessions. We look forward to a time when all students can return safely to our space. We may revisit or revise these protocols at any time based on guidance from local, national, and international public health authorities. We will provide up-to-date copies of these protocols online here: https://washingtondc.trapezeschool.com/about/COVID-19_Safety_Procedures, and hard copies will be posted widely on site. -

Trapeze in the Circus Warehouse!

Trapeze in the Circus Warehouse! Ever thought of trying out trapeze classes? Well now you definitely can at the Circus Warehouse located in Long Island City Queens. Founded in September of 2010, Circus Warehouse not only works on producing the next generation of circus performers, but also focuses on training non- pro circus enthusiasts. Static Trapeze Static Trapeze is a type of circus art performed on the trapeze bar. Unlike flying trapeze, on static trapeze the bars and ropes mainly stay in place. Most often, the static trapeze is about 1.5 feet wide and the bar is generally 2 inches in diameter. While taking a static trapeze class, you will learn to use the bar and ropes to pose, invert, balance and drop into thrilling positions. But before you get into the exciting part, there is a 30 minute workout session in order to get loosen up and get the blood flowing. After growing comfortable with solo work, you can also learn to work in pairs and teams to build shapes in the air, turning them inside out and upside down in poses that highlight both strength and flexibility. Class Prices If you are dropping in to take a single class, it will cost $65. However, you can purchase class cards depending on how many classes you are looking to take, and that also includes unlimited workout time during regular Warehouse hours until the card expires. All the equipment necessary is provided by the warehouse, so all you need to bring is a bottle of water, perhaps a towel and of course, yourself! Circus Warehouse 53-21 Vernon Blvd Long Island City, NY 11101 www.circuswarehouse.com . -

The Flying La Vans

“The Flying La Vans,” were first known by the name the “La Van Brothers” or the “Brothers La Van.” They were the first of many Bloomington born-and-bred aerial acts that formed during the ‘Golden Age’ of the circus in the U.S. in the late 1800s and continued to perform into the early twentieth century. Originally, the troupe was organized by brothers Fred and Howard Green (Greene) in 1877. Later the group include the younger brother Harry following Howard’s retirement. The La Van act, in all of its incarnations, commands a pivotal place in the history of the practice and development of the art of trapeze in the United States. FRED GREEN (1858-1897), son of John Lester Green and Harriet A. (Van Alstine) Green, was born in Bloomington, IL on March 2, 1858. Fred was one of seven children (the oldest of four sons). Like his younger brothers, Fred had a “penchant for athletics” as a child that continued to thrive in his teen years and beyond.1 Fred and his younger brother Howard (1867-1952) chose to dedicate this prowess to the study of the trapeze.2 Despite their father’s known disfavor and desire that his sons would continue the family confectionary business, Fred and Howard formed the “La Van Brothers” around 1878.”3 It is difficult to determine the exact nature of the brothers’ aerial act or exactly when the brothers first performed. For example, contrary to select sources local historian and circus enthusiast Steve Gossard proposes that the original La Van Brothers act was first a stationary bar act and not a trapeze act.4 Similarly, though some sources claim that the La Vans were the first to 1 “Fred Green is Dead; Famous Bloomington Athlete Expires in the Prime of Life,” The Pantagraph (June 15, 1897). -

Cirque Mechanics: Jan

Cirque Mechanics: Jan. 17, 2020 Cirque Cirque Mechanics 42FT – A Menagerie of Mechanical Marvels Friday, Jan. 17, 7:30 p.m. Program Act One Act Two Opening Poster Wall Justin Finds the Circus Revolving Ladder Matinee Finale Rosebud Returns The Suitcase Animal Trainer Circus Parade Knife Throwing Wheel Charivari Sword Swallowing Juggling with Rosebud Slack Wire Duo Trapeze Strong Man Log Zombie Cape Russian Swing Strong Man Bowling Balls Justin Joins the Circus Bravado Brothers Finale Juggle Go Round There will be one 20-minute intermission between acts one and two. CIRQUE MECHANICS IS REPRESENTED BY PLEASE NOTE • Latecomers will be seated at the house manager’s discretion. • Photography and video recordings of any type are strictly prohibited during the performance. • Smoking is not permitted anywhere. CU Boulder is a smoke-free campus! · cupresents.org · 303-492-8008 C-1 energy led him to “run away” with his own circus Program notes company, Cirque Mechanics. About 42ft – A Menagerie of Lashua believes that innovative mechanical Mechanical Marvels apparatus and the relationship between performer and machine sets his company apart and is at the Forty-two feet in diameter has been the measure heart of what makes Cirque Mechanics unique. of the circus ring for 250 years. Englishman Philip Lashua has delivered on this approach in the Astley discovered that horses galloping inside this company’s theatrical productions. His innovative ring provide the ideal platform for acrobatic feats. machines interact with acrobats, dancers, jugglers These equestrian acrobatics, along with clowns and contortionists on a 1920s factory floor in and flyers, are a large part of what we’ve all come Birdhouse Factory, a gold rush-era town in Boom to know as the circus. -

Academic Staff Teachers Circus Trainers

STAFF NICA Teaching Staff List Academic Staff Academic Leader Jenny Game-Lopata Head of Circus Studies James Brown – Acrobatics, Adagio, Handstands, Russian Bar, Roue Cyr, Teeterboard, Foundations VE Coordinator Tegan Carmichael – Foundations, Acrobatics, Dance Trap, Static Trap, Swinging, Single Point Aerial, Hula Hoops, Roller Skating, Group Pitching and Acrobatics Performance Coordinator Zebastian Hunter Movement Studies Coordinator Meredith Kitchen Third Year Coordinator Aaron Walker - Vertical Aerials, Dance Trapeze Second Year Coordinator Vasily Ivanov - Adagio, Contortion, Handstands, Korean Plank, Pitching, Russian Bar, Russian Swing First Year Coordinators Andrea Ousley – Performance, Aerials Emily Hughes – Cloudswing and Swinging Trapeze, Skipping, Static Trapeze, Dance Trapeze, Foundations Certificate IV Coordinator Alex Gullan - Foundations, Group Acrobatics, Trickline, Straps, Korean Plank, Wall Trampoline Certificate III Coordinator, Social Circus Coordinator Andrea Ousley - Performance, Aerials Consultant Jenni Hillman Senior Administrator Catherine Anderson Senior Administrator Jenny Vanderhorst Teachers Debra Batton – Performance Teacher Dr Rosemary Farrell – Circus History John Paul Fischbach – Arts Management Jamie Henson – Technical Aspects of Circus Dr David Munro – Anatomy & Physiology Circus Trainers Stephen Burton – Acrobatics, Comedy Acro, Hoop Diving Gang (Charlie) Cheng – Acrobatics, Chinese Pole, Handstands, Happy Cook, Unicycle, Chair Handstands Adam Davis – Chinese Pole, Acrobatics, Trampoline, Foundations,