Sean Jacobs in Conversation with Cedric Nunn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meqoqo: He Forces Us All to See Differently | The

HOME CONTRIBUTORS ABOUT US GALLERY CONTACT US SPOTLIGHT KAU KAURU VOICES PIONEERS THE CRAFT THE ARTS Meqoqo: He Forces Us All To See Differently ON THIS PAGE Photos that Inspired A Revolution open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Photos that Inspired A Revolution Omar Badsha In Conversation Did You See the Dog? Happy Native, Contented Native ByLinda Fekisi Chased girls, drank & swam Discussion LINKS Seedtime: An Omar Badsha Retrospective Professor Dilip Menon from Wits University said in an introduction of Badsha’s early work: “It is a critical reminder that the rewriting of South African art history and the full recognition of black South Africans' contributions remain an unfinished task.” Omar Badsha, considered a pioneer of “resistance art”, is one of South Visit Site Africa’s most celebrated documentary photographers. He has exhibited extensively at home and abroad and is our guest this week in our Cultural Activist occasional Meqoqo (Conversations) slot. Iziko Museums is currently Born 27 June 1945, Durban, South Africa, Badsha played an active role in hosting a retrospective exhibition entitled Seedtime at the National the South African liberation struggle, Gallery in Cape Town. It showcases Badsha’s early drawings, artworks and as a cultural and political activist and trade union leader. photographic essays, spanning a period of 50 years. The epitome of the open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com self-taught professional, he currently runs SA History Online (SAHO). Visit Site Changing focus e is a member of the post-Sharpeville generation of activist Badsha is a tall man, bespectacled, artists who, together with his close friend Dumile Feni, with thin gray hair. -

AFRAPIX SOCIAL DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY in 1980S SOUTH AFRICA

Fall 08 AFRAPIX SOCIAL DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY IN 1980s SOUTH AFRICA Amy McConaghy Acknowledgments I would like to thank Paul Weinberg, Eric Miller, Don Edkins, Graham Goddard, Zubeida Vallie and Omar Badsha for taking the time to be interviewed and for all being so incredibly obliging, kind and helpful. I thoroughly enjoyed meeting all of you and listening to your incredible stories. I would also like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Sean Field, for his excellent guidance, support and patience throughout this thesis. i Abstract This thesis examines the development of the Afrapix collective agency throughout the 1980s. It argues that despite often being confined within the context of ‘struggle photography,’ Afrapix produced a broad body of social documentary work that far exceeded the struggle. However, within the socio-political milieu photographers were working, there was limited space for a more nuanced and complex representation of South Africa. Resisting this narrow visual format, Afrapix photographers in the 1980s faced the challenge of documenting the struggle and an extended repertoire of social issues whilst expressing a nuanced and complex point of view that countered the predominant narrative. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 AFRAPIX IN CONTEXT .............................................................................................. 7 FISTS AND FLAGS PHOTOGRAPHY in the 1980s ............................................... -

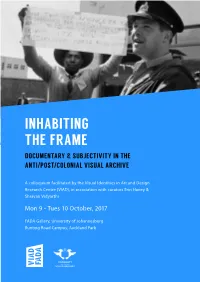

Inhabiting the Frame Documentary & Subjectivity in the Anti/Post/Colonial Visual Archive

INHABITING THE FRAME DOCUMENTARY & SUBJECTIVITY IN THE ANTI/POST/COLONIAL VISUAL ARCHIVE A colloquium facilitated by the Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre (VIAD), in association with curators Erin Haney & Shravan Vidyarthi Mon 9 - Tues 10 October, 2017 FADA Gallery, University of Johannesburg Bunting Road Campus, Auckland Park P R I Y A R A M R A K H A A Pan-African Perspective | 1950-1968 FADA Gallery, 5 October – 1 November 2017 Curated by Erin Haney and Shravan Vidyarthi Presented by the Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre (VIAD) Presented in this exhibition is the first comprehensive survey of images by pioneering Kenyan photo- journalist Priya Ramrakha. Following the recent recovery of his archive in Nairobi, the photographs on show track Ramrakha’s global travels in the 1950s and 1960s, and his sensitive chronicling of anti- colonial and post-independence struggles. Born into an activist journalistic family, Ramrakha contributed to his uncle’s paper, The Colonial Times, which subversively advocated for civil rights in colonial Kenya. Another outlet for his images was the Johannesburg-based Drum magazine, which opened an office in Nairobi in 1954. Photographing life under Kenya’s colour bar, Ramrakha’s images countered the privileged colonial purview of the mainstream press, which consistently reinforced British settler interests. This is especially evident in his coverage of Mau Mau – an anti-colonial movement discredited by British colonial propaganda as both an ‘irrational force of evil’ and a communist-inspired terrorist threat. Ramrakha’s images of detentions, roundups and urban protests tell another story; bearing witness to the severe backlash and State of Emergency enacted by the colonial administration, and characterised by mass displacement, enforced hard-labour, and horrific cases of rape, torture and murder. -

Afrapix: Some Questions Email Interview with Omar Badsha in 2009 Conducted by Marian Nur Goni for a Master’S Thesis

Afrapix: Some Questions Email interview with Omar Badsha in 2009 conducted by Marian Nur Goni for a Master’s Thesis. First, I'd like to ask you if the Culture and Resistance Festival held in Gaborone in 1982 and Afrapix setting up are linked? Yes. Afrapix and the Botswana Festival were linked. In some accounts, on the formation of Afrapix, it is argued that Afrapix was formed as a result of the Botswana Festival - that is not true. I remember seeing a document / a report which claimed that Afrapix was established by the ANC – this is also not true. Some people in Afrapix were underground members of the movement and/or sympathisers, but Afrapix was an initiative that arose out of our own internal needs and independent of the political movement, but I am sure that Paul Weinberg or some other member would have discussed the formation of Afrapix with people in Botswana. I discussed it with people in Durban. Afrapix was formally launched early in 1982. What Botswana did was to act as a platform for Afrapix and other progressive photographers to meet and develop closer working relationships. Afrapix members were closely involved in the organising of the Festival and in organising the photographic component of the Festival. Paul Weinberg and I were part of the internal organising network. We were in charge of making the arrangements for contacting photographers, collecting work and sending it to Botswana. Paul was involved with an organising group in Johannesburg and I was involved in a group around Dikobe Ben Martins in Natal. -

Between States of Emergency

BETWEEN STATES OF EMERGENCY PHOTOGRAPH © PAUL VELASCO WE SALUTE THEM The apartheid regime responded to soaring opposition in the and to unban anti-apartheid organisations. mid-1980s by imposing on South Africa a series of States of The 1985 Emergency was imposed less than two years after the United Emergency – in effect martial law. Democratic Front was launched, drawing scores of organisations under Ultimately the Emergency regulations prohibited photographers and one huge umbrella. Intending to stifle opposition to apartheid, the journalists from even being present when police acted against Emergency was first declared in 36 magisterial districts and less than a protesters and other activists. Those who dared to expose the daily year later, extended to the entire country. nationwide brutality by security forces risked being jailed. Many Thousands of men, women and children were detained without trial, photographers, journalists and activists nevertheless felt duty-bound some for years. Activists were killed, tortured and made to disappear. to show the world just how the iron fist of apartheid dealt with The country was on a knife’s edge and while the state wanted to keep opposition. the world ignorant of its crimes against humanity, many dedicated The Nelson Mandela Foundation conceived this exhibition, Between journalists shone the spotlight on its actions. States of Emergency, to honour the photographers who took a stand On 28 August 1985, when thousands of activists embarked on a march against the atrocities of the apartheid regime. Their work contributed to the prison to demand Mandela’s release, the regime reacted swiftly to increased international pressure against the South African and brutally. -

The Political Sublime. Reading Kok Nam, Mozambican Photographer (1939-2012)

The Political Sublime. Reading Kok Nam, Mozambican photographer (1939-2012) RUI ASSUBUJI History Department, University of the Western Cape PATRICIA HAYES History Department, University of the Western Cape Kok Nam began his photographic career at Studio Focus in Lourenço Marques in the 1950s, graduated to the newspaper Notícias and joined Tempo magazine in the early 1970s. Most recently he worked at the journal Savana as a photojournalist and later director. This article opens with an account of the relationship that developed between Kok Nam and the late President Samora Machel, starting with the photo- grapher’s portrait of Machel in Nachingwea in November 1974 before Independence. It traces an arc through the Popular Republic (1976-1990) from political revelation at its inception to the difficult years of civil war and Machel’s death in the plane crash at Mbuzini in 1986. The article then engages in a series of photo-commentaries across a selection of Kok Nam’s photographs, several published in their time but others selected retrospectively by Kok Nam for later exhibition and circulation. The approach taken is that of ‘association’, exploring the connections between the photographs, their histories both then and in the intervening years and other artifacts and mediums of cultural expression that deal with similar issues or signifiers picked up in the images. Among the signifiers picked up in the article are soldiers, pigs, feet, empty villages, washing, doves and bridges. The central argument is that Kok Nam participated with many others in a kind of collective hallucination during the Popular Republic, caught up in the ‘political sublime’. -

2017 07 31 Leslie Wilson Dissertation Past Black And

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PAST BLACK AND WHITE: THE COLOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN SOUTH AFRICA, 1994-2004 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY BY LESLIE MEREDITH WILSON CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 PAST BLACK AND WHITE: THE COLOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN SOUTH AFRICA, 1994-2004 * * * LIST OF FIGURES iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xv ABSTRACT xx PREFACE “Colour Photography” 1 INTRODUCTION Fixing the Rainbow: 8 The Development of Color Photography in South Africa CHAPTER 1 Seeking Spirits in Low Light: 40 Santu Mofokeng’s Chasing Shadows CHAPTER 2 Dignity in Crisis: 62 Gideon Mendel’s A Broken Landscape CHAPTER 3 In the Time of Color: 100 David Goldblatt’s Intersections CHAPTER 4 A Waking City: 140 Guy Tillim’s Jo’burg CONCLUSION Beyond the Pale 182 BIBLIOGRAPHY 189 ii LIST OF FIGURES All figures have been removed for copyright reasons. Preface i. Cover of The Reflex, November 1935 ii. E. K. Jones, Die Voorloper, 1939 iii. E. B. King, The Reaper, c. 1935 iv. Will Till, Outa, 1946 v. Broomberg and Chanarin, Kodak Ektachrome 34 1978 frame 4, 2012 vi. Broomberg and Chanarin, Shirley 2, 2012 vii. Broomberg and Chanarin, Ceramic Polaroid Sculpture, 2012. viii. Installation view of Broomberg and Chanarin, The Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement at Goodman Gallery, 2013. ix. “Focusing on Black South Africa: Returning After 8 Years, Kodak Runs into White Anger” illustration, by Donald G. McNeil, Jr., The New York Times x. Gisèle Wulfsohn, Domestic worker, Ilovo, Johannesburg, 1986. Introduction 0.1 South African Airways Advertisement, 1973. -

Africa SEEING and BEING SEEN: POLITICS, ART and THE

ٷۗۦۚۆ ېٯۆҖۛۦғۣۙۛۘۦۖۡٷғۗۧ۠ٷۢۦ۩ҖҖ۞ۣۃۤۨۨۜ ằẽẴẮẬڷۦۣۚڷ۪ۧۙۗۦۙۧڷ۠ٷۣۢۨۘۘۆ ۙۦۙۜڷ۟ۗӨ۠ڷۃۧۨۦۙ۠ٷڷ۠ٷۡٮ ۙۦۙۜڷ۟ۗӨ۠ڷۃۣۧۢۨۤۦۗۧۖ۩ۑ ۙۦۙۜڷ۟ۗӨ۠ڷۃۧۨۢۦۤۙۦڷ۠ٷۗۦӨۣۡۡۙ ۙۦۙۜڷ۟ۗӨ۠ڷۃڷۙۧ۩ڷۣۚڷۧۡۦۙے ІөۆڷےېۆڷۃۑӨٲےٲۋۍێڷۃІٮٮۑڷІٰٲٮψڷІөۆڷІٰٲٮٮۑ ІۆψېۓөڷۑھۆٱۑөۆψڷېۆیۍڷІٲڷﯦۆөﯦېٮ۔ٮڷٮٱے ۧڼہۂڽڬۧڼڿۂڽڷۃﯦٱێۆېٰۍےۍٱێ ۧۙۺٷٱڷٷۗۦۨٷێ ڿڿҢڷҒڷۀۀҢڷۤۤڷۃڽڽڼھڷۦІۣ۪ۙۡۖۙڷҖڷۀڼڷۙ۩ۧۧٲڷҖڷڽہڷۙۡ۩ۣ۠۔ڷҖڷٷۗۦۚۆ ڽڽڼھڷۦۣۙۖۨۗۍڷڿڽڷۃۣۙۢ۠ۢڷۘۙۜۧ۠ۖ۩ێڷۃڿۂҢڼڼڼڽڽڼھۀۂڽڼڼڼۑҖۀڽڼڽғڼڽڷۃٲۍө ڿۂҢڼڼڼڽڽڼھۀۂڽڼڼڼۑٵۨۗٷۦۨۧۖٷҖۛۦғۣۙۛۘۦۖۡٷғۗۧ۠ٷۢۦ۩ҖҖ۞ۣۃۤۨۨۜڷۃۙ۠ۗۨۦٷڷۧۜۨڷۣۨڷ۟ۢۋ ۃۙ۠ۗۨۦٷڷۧۜۨڷۙۨۗڷۣۨڷۣ۫ٱ ٮٱےڷІөۆڷےېۆڷۃۑӨٲےٲۋۍێڷۃІٮٮۑڷІٰٲٮψڷІөۆڷІٰٲٮٮۑڷғۀڽڽڼھڿڷۧۙۺٷٱڷٷۗۦۨٷێ ۃٷۗۦۚۆڷғۧڼہۂڽڬۧڼڿۂڽڷۃﯦٱێۆېٰۍےۍٱێڷІۆψېۓөڷۑھۆٱۑөۆψڷېۆیۍڷІٲڷﯦۆөﯦېٮ۔ٮ ڿۂҢڼڼڼڽڽڼھۀۂڽڼڼڼۑҖۀڽڼڽғڼڽۃۣۘڷڿڿҒҢۀۀҢڷۤۤڷۃڽہ ۙۦۙۜڷ۟ۗӨ۠ڷۃڷۣۧۢۧۧۡۦۙێڷۨۧۙ۩ۥۙې ҢڽڼھڷۦٷیڷۀھڷۣۢڷۀڿھҢғڿھғڽڽғڿۂڽڷۃۧۧۙۦۘۘٷڷێٲڷۃېٯۆҖۛۦғۣۙۛۘۦۖۡٷғۗۧ۠ٷۢۦ۩ҖҖ۞ۣۃۤۨۨۜڷۣۡۦۚڷۘۙۘٷөۣۣ۫ۢ۠ Africa 81 (4) 2011: 544–66 doi:10.1017/S0001972011000593 SEEING AND BEING SEEN: POLITICS, ART AND THE EVERYDAY IN OMAR BADSHA’S DURBAN PHOTOGRAPHY, 1960s–1980s Patricia Hayes THE FRAMEWORKS OF DEBATE During the 1980s when the political struggle against apartheid in South Africa was intensifying on various fronts, a photographic image began to circulate that was unusual in the growing iconography of the left (see Figure 1). It joined other social documentary and more overtly political images in press packs and other formats that entered local venues and solidarity networks abroad to muster support for the struggle. Originally taken as part of Omar Badsha’s own ‘visual diary’ in Durban in 1980, the rathi player is framed -

• Joe ALFERS • Peter AUF DER HEYDE • Omar BADSHA • Rodger

• Joe ALFERS • Peter AUF DER HEYDE • Omar BADSHA • Rodger BOSCH • Julian COBBING • Gille DE VLIEG • Brett ELOFF • Don EDKINS • Ellen ELMENDORP • Graham GODDARD • Paul GRENDON • George HALLETT • Dave HARTMAN • Steven HILTON-BARBER • Mike HUTCHINGS • Lesley LAWSON • Chris LEDOCHOWSKI • John LIEBENBERG • Herbert MABUZA • Humphrey Phakade "Pax" MAGWAZA • Kentridge MATABATHA • Jimi MATTHEWS • Rafs MAYET • Vuyi Lesley MBALO • Peter MCKENZIE • Gideon MENDEL • Roger MEINTJES • Eric MILLER • Santu MOFOKENG • Deseni MOODLIAR (Soobben) • Mxolisi MOYO • Cedric NUNN • Billy PADDOCK • Myron PETERS • Biddy PARTRIDGE • Chris QWAZI • Jeevenundhan (Jeeva) RAJGOPAUL • Wendy SCHWEGMANN • Abdul SHARIFF • Cecil SOLS • Lloyd SPENCER • Guy TILLIM • Zubeida VALLIE • Paul WEINBERG • Graeme WILLIAMS • Gisele WULFSOHN • Anna ZIEMINSKI • Morris ZWI 1 AFRAPIX PHOTOGRAPHERS, BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES • Joe ALFERS Joe (Joseph) Alfers was born in 1949 in Umbumbulu in Kwazulu Natal, where his father was the Assistant Native Commissioner. He attended school and university in Pietermaritzburg, graduating from the then University of Natal with a BA.LLB in 1972. At University, he met one of the founders of Afrapix, Paul Weinberg, who was also studying law. In 1975 he joined a commercial studio in Pietermaritzburg, Eric’s Studio, as an apprentice photographer. In 1977 he joined The Natal Witness as a photographer/reporter, and in 1979 moved to the Rand Daily Mail as a photographer. In 1979, Alfers was offered a position as Photographer/Fieldworker at the National University of Lesotho on a research project, Analysis of Rock Art in Lesotho (ARAL) which made it possible for him to evade further military service. The ARAL Project ran for four years during which time Alfers developed a photographic recording system which resulted in a uniform collection of 35,000 Kodachrome slides of rock paintings, as well as 3,500 pages of detailed site reports and maps. -

Muslim Portraits: the Anti-Apartheid Struggle

Muslim Portraits: The Anti-Apartheid Struggle Goolam Vahed Compiled for SAMNET Madiba Publishers 2012 Copyright © SAMNET 2012 Published by Madiba Publishers University of KwaZulu Natal [Howard College] King George V Avenue, Durban, 4001 No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. First Edition, First Printing 2012 Printed and bound by: Impress Printers 150 Intersite Avenue, Umgeni Business Park, Durban, South Africa ISBN: 1-874945-25-X Graphic Design by: NT Design 76 Clark Road, Glenwood, Durban, 4001 Contents Foreword 9 Yusuf Dadoo 83 Faried Ahmed Adams 17 Ayesha Dawood 89 Feroza Adams 19 Amina Desai 92 Ameen Akhalwaya 21 Barney Desai 97 Yusuf Akhalwaya 23 AKM Docrat 100 Cassim Amra 24 Cassim Docrat 106 Abdul Kader Asmal 30 Jessie Duarte 108 Mohamed Asmal 34 Ebrahim Ismail Ebrahim 109 Abu Baker Asvat 35 Gora Ebrahim 113 Zainab Asvat 40 Farid Esack 116 Saleem Badat 42 Suliman Esakjee 119 Omar Badsha 43 Karrim Essack 121 Cassim Bassa 47 Omar Essack 124 Ahmed Bhoola 49 Alie Fataar 126 Mphutlane Wa Bofelo 50 Cissie Gool 128 Amina Cachalia 51 Goolam Gool 131 Azhar Cachalia 54 Halima Gool 133 Firoz Cachalia 57 Jainub Gool 135 Moulvi Cachalia 58 Hoosen Haffejee 137 Yusuf Cachalia 60 Fatima Hajaig 140 Ameen Cajee 63 Imam Haron 142 Yunus Carrim 66 Enver Hassim 145 Achmat Cassiem 68 Kader Hassim 148 Fatima Chohan 71 Nina -

Celebrating Women in South African History ,, ,, for Freedom and Equality’ Celebrating Women in South African History

The Legacy Series’ ,, ,, For Freedom and Equality’ Celebrating Women in South African History ,, ,, For freedom and equality’ celebrating women in south african history For more information on the role of women in our history The Legacy Series visit www.sahistory.org.za , wathint , ’ abafazi, wathint ’ imbokotho , This Booklet was produced for the Department of you ve tampered with the women 978-1-4315-03903-2 , Basic Education by South African History Online you ve knocked against a rock Foreword - Celebrating the role of women in South African History and Heritage t gives me great pleasure that since I took office i as Minister of Basic Education, my Department is, for the first time, launching a publication that showcases the very important role played by the past valiant and fearless generations of women in our quest to rid our society of patriarchal oppres- sion. While most of our contemporaries across the globe had, since the twentieth century, benefited from the international instruments such as the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights and the Convention for the Elimination of Discrimina- tion against Women (CEDAW), which barred all forms of discrimination, including gender discrimi- nation, we in this Southernmost tip of the African continent continued to endure the indignity of gender discrimination across all spheres of national life. Gender oppression was particularly inhuman Minister Angie Motshekga. during apartheid, where women suffered a triple Source: Department of Basic Education. oppression of race, class and gender. The formal promulgation of the Constitution of the Republic in 1996 was an important milestone, par- ticularly for women, in our new democracy. -

Natal Indian Congress (NIC)

Natal Indian Congress (NIC) Home > Organisations > Natal Indian Congress (NIC) TOPICS1 INDIAN COMMUNITY ARCHIVE10 Resistance Politics In Retreat: Cabalism, The ANC Underground and Gandhi, 1985 -1989 View Reports of the Passive Resistance Councils: Natal and Transvaal 1946 - 1947 by E.S. Reddy & Fatima Meer View Passive Resistance 1946 - A Selection of Documents compiled by E.S. Reddy & Fatima Meer - 1948 - Press Reports on the Campaign View Passive Resistance 1946 - A Selection of Documents compiled by E.S. Reddy & Fatima Meer - Special Focus: Wrangling between political groups - 1946 View Passive Resistance 1946 - A Selection of Documents compiled by E.S. Reddy & Fatima Meer - Special Focus: Wrangling between political groups - 1947 View Passive Resistance, 1946 by E.S. Reddy & Fatima Meer - Special Focus: Wrangling between political groups - 1948View view full archive TIMELINES3 A HISTORY OF INDIANS IN SOUTH AFRICA TIMELINE: 1654-2008 MAHATMA KARAMCHAND GANDHI TIMELINE 1920-1929 INDIAN SOUTH AFRICANS TIMELINE 1940-1949 PEOPLE22 Dr Sathasivan “Saths” Cooper Professor Hoosen Mahomed "Jerry" Coovadia Abdul Khalek Mohamed Docrat Ebrahim Ismail Ebrahim Abdullah Haji Adam Jhaveri Abdulla Ismail Kajee Ismail Chota Meer Phyllis Naidoo Mewa Ramgobin Richard Albert Turner Professor Fatima Meer Kesval “Kay” Moonsamy Sorabjee Rustomjee Fatima Seedat Hassim Ebrahim Mall Roy Padayachie Rustomjee Jiwanji Ghorkhodu Cassim Amra Pravin Jamnadas Gordhan David Perumal Natvarlal Dayalji “Natoo” Babenia Subbiah Moodley ORGANISATIONS1 African National Congress (ANC) 1946 Resistance Camp. Private Collection, Omar Badsha The NIC (Natal Indian Congress) was the first of the Indian Congresses to be formed. It was established in 1894 by Mahatma Gandhi to fight discrimination against Indian traders in Natal.