Read Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meqoqo: He Forces Us All to See Differently | The

HOME CONTRIBUTORS ABOUT US GALLERY CONTACT US SPOTLIGHT KAU KAURU VOICES PIONEERS THE CRAFT THE ARTS Meqoqo: He Forces Us All To See Differently ON THIS PAGE Photos that Inspired A Revolution open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Photos that Inspired A Revolution Omar Badsha In Conversation Did You See the Dog? Happy Native, Contented Native ByLinda Fekisi Chased girls, drank & swam Discussion LINKS Seedtime: An Omar Badsha Retrospective Professor Dilip Menon from Wits University said in an introduction of Badsha’s early work: “It is a critical reminder that the rewriting of South African art history and the full recognition of black South Africans' contributions remain an unfinished task.” Omar Badsha, considered a pioneer of “resistance art”, is one of South Visit Site Africa’s most celebrated documentary photographers. He has exhibited extensively at home and abroad and is our guest this week in our Cultural Activist occasional Meqoqo (Conversations) slot. Iziko Museums is currently Born 27 June 1945, Durban, South Africa, Badsha played an active role in hosting a retrospective exhibition entitled Seedtime at the National the South African liberation struggle, Gallery in Cape Town. It showcases Badsha’s early drawings, artworks and as a cultural and political activist and trade union leader. photographic essays, spanning a period of 50 years. The epitome of the open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com self-taught professional, he currently runs SA History Online (SAHO). Visit Site Changing focus e is a member of the post-Sharpeville generation of activist Badsha is a tall man, bespectacled, artists who, together with his close friend Dumile Feni, with thin gray hair. -

AFRAPIX SOCIAL DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY in 1980S SOUTH AFRICA

Fall 08 AFRAPIX SOCIAL DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY IN 1980s SOUTH AFRICA Amy McConaghy Acknowledgments I would like to thank Paul Weinberg, Eric Miller, Don Edkins, Graham Goddard, Zubeida Vallie and Omar Badsha for taking the time to be interviewed and for all being so incredibly obliging, kind and helpful. I thoroughly enjoyed meeting all of you and listening to your incredible stories. I would also like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Sean Field, for his excellent guidance, support and patience throughout this thesis. i Abstract This thesis examines the development of the Afrapix collective agency throughout the 1980s. It argues that despite often being confined within the context of ‘struggle photography,’ Afrapix produced a broad body of social documentary work that far exceeded the struggle. However, within the socio-political milieu photographers were working, there was limited space for a more nuanced and complex representation of South Africa. Resisting this narrow visual format, Afrapix photographers in the 1980s faced the challenge of documenting the struggle and an extended repertoire of social issues whilst expressing a nuanced and complex point of view that countered the predominant narrative. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 AFRAPIX IN CONTEXT .............................................................................................. 7 FISTS AND FLAGS PHOTOGRAPHY in the 1980s ............................................... -

Biko Met I Must Say, He Nontsikelelo (Ntsiki) Mashalaba

LOVE AND MARRIAGE In Durban in early 1970, Biko met I must say, he Nontsikelelo (Ntsiki) Mashalaba Steve Biko Foundation was very politically who came from Umthatha in the Transkei. She was pursuing involved then as her nursing training at King Edward Hospital while Biko was president of SASO. a medical student at the I remember we University of Natal. used to make appointments and if he does come he says, “Take me to the station – I’ve Daily Dispatch got a meeting in Johannesburg tomorrow”. So I happened to know him that way, and somehow I fell for him. Ntsiki Biko Daily Dispatch During his years at Ntsiki and Steve university in Natal, Steve had two sons together, became very close to his eldest Nkosinathi (left) and sister, Bukelwa, who was a student Samora (right) pictured nurse at King Edward Hospital. here with Bandi. Though Bukelwa was homesick In all Biko had four and wanted to return to the Eastern children — Nkosinathi, Cape, she expresses concern Samora, Hlumelo about leaving Steve in Natal and Motlatsi. in this letter to her mother in1967: He used to say to his friends, “Meet my lady ... she is the actual embodiment of blackness - black is beautiful”. Ntsiki Biko Daily Dispatch AN ATTITUDE OF MIND, A WAY OF LIFE SASO spread like wildfire through the black campuses. It was not long before the organisation became the most formidable political force on black campuses across the country and beyond. SASO encouraged black students to see themselves as black before they saw themselves as students. SASO saw itself Harry Nengwekhulu was the SRC president at as part of the black the University of the North liberation movement (Turfloop) during the late before it saw itself as a Bailey’s African History Archive 1960s. -

Does Black Theology Have a Role to Play in The

Prof. R.T.H. Dolamo Department of DOES BLACK THEOLOGY Philosophy, Practical and Systematic HAVE A ROLE TO PLAY Theology, University of South Africa. IN THE DEMOCRATIC [email protected] SOUTH AFRICA? DOI: http://dx.doi. ABSTRACT org/10.4314/actat. v36i1.4S Black theology was conceived in South Africa in the mid-1960s and flourished from the 1970s, when White ISSN 1015-8758 (Print) supremacy perpetuated by the apartheid state was at its ISSN 2309-9089 (Online) zenith. The struggle against apartheid was aimed mainly at Acta Theologica 2016 attaining national political liberation so much so that other Suppl 24:43-61 forms of freedom, albeit implied and included indirectly in the liberation agenda, were not regarded as immediate © UV/UFS priorities. Yet two decades into our democracy, poverty, racism, gender injustice, patriarchy, xenophobia, bad governance, environmental degradation, and so on need to be prophetically addressed with equal seriousness and simultaneously, for none of these issues can be left for some time in the future. Using Black Consciousness as a handmaid, Black theology can meaningfully play a role in the democratic South Africa. 1. INTRODUCTION According to Motlhabi (2009:173), Black Theology in South Africa (BTSA) needs to develop a new paradigm urgently: a paradigm that will address itself to the multiple present-day problems and evils such as ongoing poverty, slum-dwelling, crime, family violence, and child abuse, HIV/AIDS, corruption and greed in public and private service, and other related evils still bedevilling South Africa today. Prior to 1994, South African liberation movements had their eyes fixed almost exclusively on national political liberation. -

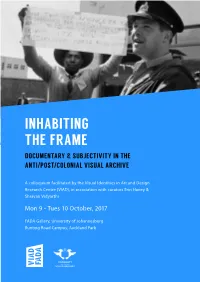

Inhabiting the Frame Documentary & Subjectivity in the Anti/Post/Colonial Visual Archive

INHABITING THE FRAME DOCUMENTARY & SUBJECTIVITY IN THE ANTI/POST/COLONIAL VISUAL ARCHIVE A colloquium facilitated by the Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre (VIAD), in association with curators Erin Haney & Shravan Vidyarthi Mon 9 - Tues 10 October, 2017 FADA Gallery, University of Johannesburg Bunting Road Campus, Auckland Park P R I Y A R A M R A K H A A Pan-African Perspective | 1950-1968 FADA Gallery, 5 October – 1 November 2017 Curated by Erin Haney and Shravan Vidyarthi Presented by the Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre (VIAD) Presented in this exhibition is the first comprehensive survey of images by pioneering Kenyan photo- journalist Priya Ramrakha. Following the recent recovery of his archive in Nairobi, the photographs on show track Ramrakha’s global travels in the 1950s and 1960s, and his sensitive chronicling of anti- colonial and post-independence struggles. Born into an activist journalistic family, Ramrakha contributed to his uncle’s paper, The Colonial Times, which subversively advocated for civil rights in colonial Kenya. Another outlet for his images was the Johannesburg-based Drum magazine, which opened an office in Nairobi in 1954. Photographing life under Kenya’s colour bar, Ramrakha’s images countered the privileged colonial purview of the mainstream press, which consistently reinforced British settler interests. This is especially evident in his coverage of Mau Mau – an anti-colonial movement discredited by British colonial propaganda as both an ‘irrational force of evil’ and a communist-inspired terrorist threat. Ramrakha’s images of detentions, roundups and urban protests tell another story; bearing witness to the severe backlash and State of Emergency enacted by the colonial administration, and characterised by mass displacement, enforced hard-labour, and horrific cases of rape, torture and murder. -

South Africa's Elections

South Africa’s elections: no change? Standard Note: SN05983 Last updated: 15 May 2014 Author: Jon Lunn Section International Affairs and Defence Section On 7 May 2014, South Africa held its fifth national and provincial elections since the end of Apartheid. The four best performing parties in the 400-seat National Assembly elections were as follows: Share Seats Party of vote AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 62.15% 249 DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE 22.23% 89 ECONOMIC FREEDOM FIGHTERS 6.35% 25 INKATHA FREEDOM PARTY 2.40% 10 The remaining 27 seats were shared amongst nine parties each of which gained less than 2%. The ruling ANC won all the provincial elections with the exception of the Western Cape, where the DA retained power. So were the elections a case of no change? Yes and no. The ANC’s political dominance remains unchallenged. Its overall share of the vote in 2014 was down 3.75% on 2009. But this seems a small drop in support given the relatively poor ratings given by some commentators to President Jacob Zuma, who is now set for a second term in office, for his performance over the past five years. The centre-right DA added 7.57% to its vote as compared with last time around. It improved its political position without transforming it. The Inkatha Freedom Party continued its gradual political decline, losing 2.15%. Last but not least, the EFF, which is largely composed of ex- ANC radicals, largely supplanted the Congress of the People, also the creation of disillusioned ANC members, which scored 7.42% in 2009 but then subsequently imploded. -

Dispossession, Displacement, and the Making of the Shared Minibus Taxi in Cape Town and Johannesburg, South Africa, 1930-Present

Sithutha Isizwe (“We Carry the Nation”): Dispossession, Displacement, and the Making of the Shared Minibus Taxi in Cape Town and Johannesburg, South Africa, 1930-Present A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Elliot Landon James IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Allen F. Isaacman & Helena Pohlandt-McCormick November 2018 Elliot Landon James 2018 copyright Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................. ii List of Abbreviations ......................................................................................................iii Prologue .......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1 ....................................................................................................................... 17 Introduction: Dispossession and Displacement: Questions Framing Thesis Chapter 2 ....................................................................................................................... 94 Historical Antecedents of the Shared Minibus Taxi: The Cape Colony, 1830-1930 Chapter 3 ..................................................................................................................... 135 Apartheid, Forced Removals, and Public Transportation in Cape Town, 1945-1978 Chapter 4 .................................................................................................................... -

Mont Fleur Scenarios

T he story of South Africas transition in 1994 to a non-racial democracy has been told many times, principally from the perspective of the political forces for change. But many other factors were at work, over many years, BREAKING THE MOULD which influenced not only the political outcome but also the economic philosophy of the new ANC government. This pioneering study explores one such set of factors, viz the ideas generated by three quite different privately initiated but publicly disseminated scenario exercises undertaken in the period 1985-1992. In doing so, and in locating the scenarios within the turbulent context of the times, it offers fresh and compelling insights into the transition as well as into the fierce contestation over political and economic ideas, which continues to the present day. The book goes beyond this. It draws on South Africas unusually rich experience of scenario work to illuminate the circumstances in which the method can be fruitfully used as well as the key factors that must be taken into account in designing, conducting and communicating the projects output. And it points to the pitfalls if these matters are not properly addressed. Nick Segal has had a varied career. He has held senior positions in the World Bank in Washington DC and in a major consultancy in the City of London and was the founder of SQW, an economic development and public policy consultancy headquartered in Cambridge, England. In South Africa he has been a director of mining companies (and served as the president of the Chamber of Mines) and dean/director of the Graduate School of Business NICK SEGAL at the University of Cape Town, and is currently an extraordinary professor at the Gordon Institute of Business Science of the University of Pretoria. -

South Africa: the 2014 National and Provincial Elections, In: Africa Spectrum, 49, 2, 79-89

Africa Spectrum Engel, Ulf (2014), South Africa: The 2014 National and Provincial Elections, in: Africa Spectrum, 49, 2, 79-89. URN: http://nbn-resolving.org/urn/resolver.pl?urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-4-7550 ISSN: 1868-6869 (online), ISSN: 0002-0397 (print) The online version of this and the other articles can be found at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Published by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Institute of African Affairs in co-operation with the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation Uppsala and Hamburg University Press. Africa Spectrum is an Open Access publication. It may be read, copied and distributed free of charge according to the conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. To subscribe to the print edition: <[email protected]> For an e-mail alert please register at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Africa Spectrum is part of the GIGA Journal Family which includes: Africa Spectrum ●● Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs ●● Journal of Politics in Latin America <www.giga-journal-family.org> Africa Spectrum 2/2014: 79-89 South Africa: The 2014 National and Provincial Elections Ulf Engel Abstract: On 7 May 2014, South Africa held its fifth national and pro- vincial elections since the end of apartheid in 1994. Despite a degree of discontent, the ANC remained firmly in power, receiving 62.15 per cent of the vote. Frustration about non-delivery of services, autocratic tendencies within the ruling party and widespread corrupt practices did not translate into substantially more votes for opposition parties, except in the Western Cape and Gauteng regions (and a swing vote from COPE to DA in Northern Cape). -

Afrapix: Some Questions Email Interview with Omar Badsha in 2009 Conducted by Marian Nur Goni for a Master’S Thesis

Afrapix: Some Questions Email interview with Omar Badsha in 2009 conducted by Marian Nur Goni for a Master’s Thesis. First, I'd like to ask you if the Culture and Resistance Festival held in Gaborone in 1982 and Afrapix setting up are linked? Yes. Afrapix and the Botswana Festival were linked. In some accounts, on the formation of Afrapix, it is argued that Afrapix was formed as a result of the Botswana Festival - that is not true. I remember seeing a document / a report which claimed that Afrapix was established by the ANC – this is also not true. Some people in Afrapix were underground members of the movement and/or sympathisers, but Afrapix was an initiative that arose out of our own internal needs and independent of the political movement, but I am sure that Paul Weinberg or some other member would have discussed the formation of Afrapix with people in Botswana. I discussed it with people in Durban. Afrapix was formally launched early in 1982. What Botswana did was to act as a platform for Afrapix and other progressive photographers to meet and develop closer working relationships. Afrapix members were closely involved in the organising of the Festival and in organising the photographic component of the Festival. Paul Weinberg and I were part of the internal organising network. We were in charge of making the arrangements for contacting photographers, collecting work and sending it to Botswana. Paul was involved with an organising group in Johannesburg and I was involved in a group around Dikobe Ben Martins in Natal. -

Between States of Emergency

BETWEEN STATES OF EMERGENCY PHOTOGRAPH © PAUL VELASCO WE SALUTE THEM The apartheid regime responded to soaring opposition in the and to unban anti-apartheid organisations. mid-1980s by imposing on South Africa a series of States of The 1985 Emergency was imposed less than two years after the United Emergency – in effect martial law. Democratic Front was launched, drawing scores of organisations under Ultimately the Emergency regulations prohibited photographers and one huge umbrella. Intending to stifle opposition to apartheid, the journalists from even being present when police acted against Emergency was first declared in 36 magisterial districts and less than a protesters and other activists. Those who dared to expose the daily year later, extended to the entire country. nationwide brutality by security forces risked being jailed. Many Thousands of men, women and children were detained without trial, photographers, journalists and activists nevertheless felt duty-bound some for years. Activists were killed, tortured and made to disappear. to show the world just how the iron fist of apartheid dealt with The country was on a knife’s edge and while the state wanted to keep opposition. the world ignorant of its crimes against humanity, many dedicated The Nelson Mandela Foundation conceived this exhibition, Between journalists shone the spotlight on its actions. States of Emergency, to honour the photographers who took a stand On 28 August 1985, when thousands of activists embarked on a march against the atrocities of the apartheid regime. Their work contributed to the prison to demand Mandela’s release, the regime reacted swiftly to increased international pressure against the South African and brutally. -

The Political Sublime. Reading Kok Nam, Mozambican Photographer (1939-2012)

The Political Sublime. Reading Kok Nam, Mozambican photographer (1939-2012) RUI ASSUBUJI History Department, University of the Western Cape PATRICIA HAYES History Department, University of the Western Cape Kok Nam began his photographic career at Studio Focus in Lourenço Marques in the 1950s, graduated to the newspaper Notícias and joined Tempo magazine in the early 1970s. Most recently he worked at the journal Savana as a photojournalist and later director. This article opens with an account of the relationship that developed between Kok Nam and the late President Samora Machel, starting with the photo- grapher’s portrait of Machel in Nachingwea in November 1974 before Independence. It traces an arc through the Popular Republic (1976-1990) from political revelation at its inception to the difficult years of civil war and Machel’s death in the plane crash at Mbuzini in 1986. The article then engages in a series of photo-commentaries across a selection of Kok Nam’s photographs, several published in their time but others selected retrospectively by Kok Nam for later exhibition and circulation. The approach taken is that of ‘association’, exploring the connections between the photographs, their histories both then and in the intervening years and other artifacts and mediums of cultural expression that deal with similar issues or signifiers picked up in the images. Among the signifiers picked up in the article are soldiers, pigs, feet, empty villages, washing, doves and bridges. The central argument is that Kok Nam participated with many others in a kind of collective hallucination during the Popular Republic, caught up in the ‘political sublime’.