New York Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© 2017 SUNHEE JANG All Rights Reserved

© 2017 SUNHEE JANG All Rights Reserved CONTEMPORARY ART AND THE SEARCH FOR HISTORY —THE EMERGENCE OF THE ARTIST-HISTORIAN— BY SUNHEE JANG DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2017 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Terri Weissman, Chair Associate Professor David O’Brien Assistant Professor Sandy Prita Meier Associate Professor Kevin Hamilton ABSTRACT Focusing on the concept of the artist-as-historian, this dissertation examines the work of four contemporary artists in a transnational context. In chapter one, I examine the representations of economic inequality and globalization (Allan Sekula, the United States); in chapter two, the racial memory and remnants of colonialism (Santu Mofokeng, South Africa); and in chapter three, the trauma of civil war and subsequent conflicts (Akram Zaatari, Lebanon and Chan- kyong Park, South Korea). My focus is on photographic projects—a photobook (Sekula), a private album (Mofokeng), and archives and films (Zaatari and Park)—that address key issues of underrepresented history at the end of the twentieth century. Chapter one concentrates on how to make sense of the complex structure of Sekula’s Fish Story (1995) and suggests the concept of surface reading as an alternative to traditional, symptomatic reading and posits that some historical truths can be found by closely examining the surface of events or images. In Fish Story, photographs represent the surface of our globe, while the text reveals the narratives that have been complicated beneath that surface. I then analyze how three types of text—caption, description, and essay—interact with images. -

Meqoqo: He Forces Us All to See Differently | The

HOME CONTRIBUTORS ABOUT US GALLERY CONTACT US SPOTLIGHT KAU KAURU VOICES PIONEERS THE CRAFT THE ARTS Meqoqo: He Forces Us All To See Differently ON THIS PAGE Photos that Inspired A Revolution open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Photos that Inspired A Revolution Omar Badsha In Conversation Did You See the Dog? Happy Native, Contented Native ByLinda Fekisi Chased girls, drank & swam Discussion LINKS Seedtime: An Omar Badsha Retrospective Professor Dilip Menon from Wits University said in an introduction of Badsha’s early work: “It is a critical reminder that the rewriting of South African art history and the full recognition of black South Africans' contributions remain an unfinished task.” Omar Badsha, considered a pioneer of “resistance art”, is one of South Visit Site Africa’s most celebrated documentary photographers. He has exhibited extensively at home and abroad and is our guest this week in our Cultural Activist occasional Meqoqo (Conversations) slot. Iziko Museums is currently Born 27 June 1945, Durban, South Africa, Badsha played an active role in hosting a retrospective exhibition entitled Seedtime at the National the South African liberation struggle, Gallery in Cape Town. It showcases Badsha’s early drawings, artworks and as a cultural and political activist and trade union leader. photographic essays, spanning a period of 50 years. The epitome of the open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com self-taught professional, he currently runs SA History Online (SAHO). Visit Site Changing focus e is a member of the post-Sharpeville generation of activist Badsha is a tall man, bespectacled, artists who, together with his close friend Dumile Feni, with thin gray hair. -

AFRAPIX SOCIAL DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY in 1980S SOUTH AFRICA

Fall 08 AFRAPIX SOCIAL DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY IN 1980s SOUTH AFRICA Amy McConaghy Acknowledgments I would like to thank Paul Weinberg, Eric Miller, Don Edkins, Graham Goddard, Zubeida Vallie and Omar Badsha for taking the time to be interviewed and for all being so incredibly obliging, kind and helpful. I thoroughly enjoyed meeting all of you and listening to your incredible stories. I would also like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Sean Field, for his excellent guidance, support and patience throughout this thesis. i Abstract This thesis examines the development of the Afrapix collective agency throughout the 1980s. It argues that despite often being confined within the context of ‘struggle photography,’ Afrapix produced a broad body of social documentary work that far exceeded the struggle. However, within the socio-political milieu photographers were working, there was limited space for a more nuanced and complex representation of South Africa. Resisting this narrow visual format, Afrapix photographers in the 1980s faced the challenge of documenting the struggle and an extended repertoire of social issues whilst expressing a nuanced and complex point of view that countered the predominant narrative. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 AFRAPIX IN CONTEXT .............................................................................................. 7 FISTS AND FLAGS PHOTOGRAPHY in the 1980s ............................................... -

Recent Histories Contemporary African Photography and Video Art in Dialogue with African Photography from Huis Marseille’S Collection

date/16.10.2018 Press release 1/4 Recent Histories Contemporary African photography and video art in dialogue with African photography from Huis Marseille’s collection 8 September – 2 December 2018 • A unique collaboration between Huis Marseille and The Walther Collection • Work by rising African photographers exhibited for the first time in the Netherlands • Stories of identity, migration, and the legacy of colonialism and apartheid • An ode to the recently deceased South African photographer David Goldblatt For the exhibition Recent Histories, Huis Marseille and The Walther Collection (New York/Neu-Ulm) have joined forces to present a unique collection of African photography and video art. African photography is at the heart of the collection policies of both institutes, and for this exhibition Huis Marseille has been able to make a broad selection from The Walther Collection’s exhibition of the same name that was shown in 2017 in Neu-Ulm. In Amsterdam, Recent Histories combines the recent work of young African photographers with the work of several generations of African photographers in the Huis Marseille collection and the Han Nefkens H+F Collection – from David Goldblatt (1930– 2018), the ‘grand old man’ of South African photography, to Lebohang Kganye (1990), who finished her training in Johannesburg as recently as 2011. The exhibition brings together these photographers’ different perspectives on their countries and their continent. The themes that link their work are concerned with identity, migration, origins, and the legacy of colonialism, in relation to their own personal experiences. 2/4 Stories The title of the exhibition refers to the narratives and histories that meet in the work of these photographers and artists, now overlapping and then going in different directions. -

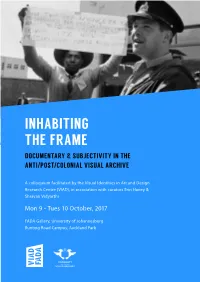

Inhabiting the Frame Documentary & Subjectivity in the Anti/Post/Colonial Visual Archive

INHABITING THE FRAME DOCUMENTARY & SUBJECTIVITY IN THE ANTI/POST/COLONIAL VISUAL ARCHIVE A colloquium facilitated by the Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre (VIAD), in association with curators Erin Haney & Shravan Vidyarthi Mon 9 - Tues 10 October, 2017 FADA Gallery, University of Johannesburg Bunting Road Campus, Auckland Park P R I Y A R A M R A K H A A Pan-African Perspective | 1950-1968 FADA Gallery, 5 October – 1 November 2017 Curated by Erin Haney and Shravan Vidyarthi Presented by the Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre (VIAD) Presented in this exhibition is the first comprehensive survey of images by pioneering Kenyan photo- journalist Priya Ramrakha. Following the recent recovery of his archive in Nairobi, the photographs on show track Ramrakha’s global travels in the 1950s and 1960s, and his sensitive chronicling of anti- colonial and post-independence struggles. Born into an activist journalistic family, Ramrakha contributed to his uncle’s paper, The Colonial Times, which subversively advocated for civil rights in colonial Kenya. Another outlet for his images was the Johannesburg-based Drum magazine, which opened an office in Nairobi in 1954. Photographing life under Kenya’s colour bar, Ramrakha’s images countered the privileged colonial purview of the mainstream press, which consistently reinforced British settler interests. This is especially evident in his coverage of Mau Mau – an anti-colonial movement discredited by British colonial propaganda as both an ‘irrational force of evil’ and a communist-inspired terrorist threat. Ramrakha’s images of detentions, roundups and urban protests tell another story; bearing witness to the severe backlash and State of Emergency enacted by the colonial administration, and characterised by mass displacement, enforced hard-labour, and horrific cases of rape, torture and murder. -

Marian Goodman Gallery David Goldblatt

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY DAVID GOLDBLATT Birth 1930, Randfontein, South Africa Death 2018, Johannesburg, South Africa Awards: 2015 Kraszna-Krausz Fellowship Award 2013 ICP Lifetime Achievement award from the International Center of Photography, New York 2011 Honorary Doctorate San Francisco Art Institute 2011 Kraszna-Krausz Photography Book award (with Ivan Vladislavic) 2010 Lucie Award Lifetime Achievement Honoree 2009 Henri Cartier- Bresson Award, France 2008 Honorary Doctorate of Literature, University of Witwatersrand 2009 Lifetime Achievement Award, Arts and Culture Trust 2006 HASSELBLAD PHOTOGRAPHY AWARD 2004 “Rencontres d’Arles” Book Award for his book ‘Particulars’ 2001 Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts, University of Cape Town 1995 Camera Austria Prize SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 David Goldblatt: 1948-2018, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia David Goldblatt, Structures de domination et de démocratie, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France David Goldblatt, Librairie Marian Goodman, Paris 2016 Ex-Offenders, Pace Gallery, New York, USA 2015 Structures of Dominion and Democracy, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa David Goldblatt, The Pursuit of Values Standard Bank Gallery, Johannesburg, South Africa 2014 Structures of Dominion and Democracy, Galerie Marian Goodman, Paris, France Structures of Dominion and Democracy in South Africa, Minneapolis Institute of Art, USA New Pictures 10: David Goldblatt, Structures of Dominion and Democracy, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, United States 2012 On the Mines, The Goodman -

South African Photography of the HIV Epidemic

Strategies of Representation: South African Photography of the HIV Epidemic Annabelle Wienand Supervisor: Professor Michael GodbyTown Co-supervisor: Professor Nicoli Nattrass Cape Thesis presentedof for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Visual and Art History Michaelis School of Fine Art University of Cape Town University February 2014 University of Cape Town The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University This thesis is dedicated to Michael Godby and Nicoli Nattrass Abstract This thesis is concerned with how South African photographers have responded to the HIV epidemic. The focus is on the different visual, political and intellectual strategies that photographers have used to document the disease and the complex issues that surround it. The study considers the work of all South African photographers who have produced a comprehensive body of work on HIV and AIDS. This includes both published and unpublished work. The analysis of the photographic work is situated in relation to other histories including the history of photography in Africa, the documentation of the HIV epidemic since the 1980s, and the political and social experience of the epidemic in South Africa. The reading of the photographs is also informed by the contexts where they are published or exhibited, including the media, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and aid organisations, and the fine art gallery and attendant publications. -

Afrapix: Some Questions Email Interview with Omar Badsha in 2009 Conducted by Marian Nur Goni for a Master’S Thesis

Afrapix: Some Questions Email interview with Omar Badsha in 2009 conducted by Marian Nur Goni for a Master’s Thesis. First, I'd like to ask you if the Culture and Resistance Festival held in Gaborone in 1982 and Afrapix setting up are linked? Yes. Afrapix and the Botswana Festival were linked. In some accounts, on the formation of Afrapix, it is argued that Afrapix was formed as a result of the Botswana Festival - that is not true. I remember seeing a document / a report which claimed that Afrapix was established by the ANC – this is also not true. Some people in Afrapix were underground members of the movement and/or sympathisers, but Afrapix was an initiative that arose out of our own internal needs and independent of the political movement, but I am sure that Paul Weinberg or some other member would have discussed the formation of Afrapix with people in Botswana. I discussed it with people in Durban. Afrapix was formally launched early in 1982. What Botswana did was to act as a platform for Afrapix and other progressive photographers to meet and develop closer working relationships. Afrapix members were closely involved in the organising of the Festival and in organising the photographic component of the Festival. Paul Weinberg and I were part of the internal organising network. We were in charge of making the arrangements for contacting photographers, collecting work and sending it to Botswana. Paul was involved with an organising group in Johannesburg and I was involved in a group around Dikobe Ben Martins in Natal. -

Between States of Emergency

BETWEEN STATES OF EMERGENCY PHOTOGRAPH © PAUL VELASCO WE SALUTE THEM The apartheid regime responded to soaring opposition in the and to unban anti-apartheid organisations. mid-1980s by imposing on South Africa a series of States of The 1985 Emergency was imposed less than two years after the United Emergency – in effect martial law. Democratic Front was launched, drawing scores of organisations under Ultimately the Emergency regulations prohibited photographers and one huge umbrella. Intending to stifle opposition to apartheid, the journalists from even being present when police acted against Emergency was first declared in 36 magisterial districts and less than a protesters and other activists. Those who dared to expose the daily year later, extended to the entire country. nationwide brutality by security forces risked being jailed. Many Thousands of men, women and children were detained without trial, photographers, journalists and activists nevertheless felt duty-bound some for years. Activists were killed, tortured and made to disappear. to show the world just how the iron fist of apartheid dealt with The country was on a knife’s edge and while the state wanted to keep opposition. the world ignorant of its crimes against humanity, many dedicated The Nelson Mandela Foundation conceived this exhibition, Between journalists shone the spotlight on its actions. States of Emergency, to honour the photographers who took a stand On 28 August 1985, when thousands of activists embarked on a march against the atrocities of the apartheid regime. Their work contributed to the prison to demand Mandela’s release, the regime reacted swiftly to increased international pressure against the South African and brutally. -

The Political Sublime. Reading Kok Nam, Mozambican Photographer (1939-2012)

The Political Sublime. Reading Kok Nam, Mozambican photographer (1939-2012) RUI ASSUBUJI History Department, University of the Western Cape PATRICIA HAYES History Department, University of the Western Cape Kok Nam began his photographic career at Studio Focus in Lourenço Marques in the 1950s, graduated to the newspaper Notícias and joined Tempo magazine in the early 1970s. Most recently he worked at the journal Savana as a photojournalist and later director. This article opens with an account of the relationship that developed between Kok Nam and the late President Samora Machel, starting with the photo- grapher’s portrait of Machel in Nachingwea in November 1974 before Independence. It traces an arc through the Popular Republic (1976-1990) from political revelation at its inception to the difficult years of civil war and Machel’s death in the plane crash at Mbuzini in 1986. The article then engages in a series of photo-commentaries across a selection of Kok Nam’s photographs, several published in their time but others selected retrospectively by Kok Nam for later exhibition and circulation. The approach taken is that of ‘association’, exploring the connections between the photographs, their histories both then and in the intervening years and other artifacts and mediums of cultural expression that deal with similar issues or signifiers picked up in the images. Among the signifiers picked up in the article are soldiers, pigs, feet, empty villages, washing, doves and bridges. The central argument is that Kok Nam participated with many others in a kind of collective hallucination during the Popular Republic, caught up in the ‘political sublime’. -

Sean Jacobs in Conversation with Cedric Nunn

This article was downloaded by: [The Library, University of Witwatersrand] On: 30 July 2012, At: 23:14 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Social Dynamics: A journal of African studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsdy20 Sean Jacobs in conversation with Cedric Nunn Sean Jacobs a & Cedric Nunn b a International Affairs, The New School, New York, USA b KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa Version of record first published: 13 Oct 2011 To cite this article: Sean Jacobs & Cedric Nunn (2011): Sean Jacobs in conversation with Cedric Nunn, Social Dynamics: A journal of African studies, 37:2, 278-288 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02533952.2011.603601 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Afrique Du Sud. Photographie Contemporaine

David Goldblatt, Stalled municipal housing scheme, Kwezidnaledi, Lady Grey, Eastern Cape, 5 August 2006, de la série Intersections Intersected, 2008, archival pigment ink digitally printed on cotton rag paper, 99x127 cm AFRIQUE DU SUD Cours de Nassim Daghighian 2 Quelques photographes et artistes contemporains d'Afrique du Sud (ordre alphabétique) Jordi Bieber ♀ (1966, Johannesburg ; vit à Johannesburg) www.jodibieber.com Ilan Godfrey (1980, Johannesburg ; vit à Londres, Grande-Bretagne) www.ilangodfrey.com David Goldblatt (1930, Randfontein, Transvaal, Afrique du Sud ; vit à Johannesburg) Kay Hassan (1956, Johannesburg ; vit à Johannesburg) Pieter Hugo (1976, Johannesburg ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) www.pieterhugo.com Nomusa Makhubu ♀ (1984, Sebokeng ; vit à Grahamstown) Lebohang Mashiloane (1981, province de l'Etat-Libre) Nandipha Mntambo ♀ (1982, Swaziland ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) Zwelethu Mthethwa (1960, Durban ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) Zanele Muholi ♀ (1972, Umlazi, Durban ; vit à Johannesburg) Riason Naidoo (1970, Chatsworth, Durban ; travaille à la Galerie national d'Afrique du Sud au Cap) Tracey Rose ♀ (1974, Durban, Afrique du Sud ; vit à Johannesburg) Berni Searle ♀ (1964, Le Cap / Cape Town ; vit au Cap) Mikhael Subotsky (1981, Le Cap / Cape Town ; vit à Johannesburg) Guy Tillim (1962, Johannesburg ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) Nontsikelelo "Lolo" Veleko ♀ (1977, Bodibe, North West Province ; vit à Johannesburg) Alastair Whitton (1969, Glasgow, Ecosse ; vit au Cap) Graeme Williams (1961, Le Cap / Cape Town ; vit à Johannesburg) Références bibliographiques Black, Brown, White. Photography from South Africa, Vienne, Kunsthalle Wien 2006 ENWEZOR, Okwui, Snap Judgments. New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, cat. expo. 10.03.-28.05.06, New York, International Center of Photography / Göttingen, Steidl, 2006 Bamako 2007.