The Corona Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RSF WAS FOUNDED on the CONCEPT of Service Through Finance for Social Benefit

rsf MARCH 31, 2005 QuarterlyAN IMPACT REPORT OF THE RUDOLF STEINER FOUNDATION’S ACTIVITIES IN THIS ISSUE RSF WAS FOUNDED ON THE CONCEPT of service through finance for social benefit. As we look back at 2004 and forge ahead into 2005, we find ourselves, our investors, donors, and RSF Facts at a Glance . 1 borrowers increasingly active and leading partners in the growth of social finance. We Projects Funded This have not only been visible via projects we fund and other activities, but also present at Quarter . 2 many important events that speak to a future in which the world works with money with President’s Letter 3 . a new consciousness. In this issue, we reflect back on 2004 in pictures, financial high- 2004 Year in Review . 4 – 8 lights, and select stories. Most notably, a letter from Mark Finser offers his insights into Stories of how RSF, through its donors, the year just past, and a sense of anticipation for the year ahead. But, we would be remiss investors, borrowers, and grant recipients, if we did not also keep you up to date on the positive impact we are having on the world have effected the lives of many through all of our programs. We hope you enjoy this issue of the RSF Quarterly and we Images and Linkages . 9 look forward to your continued interest. RSF 2004 Consolidated Financial Highlights . 10 New RSF Funds. 11 Creating Social Benefit Through Projects About RSF . 12 We Fund In this issue, we present a few stories of how RSF, through the support of donors, investors, and borrowers, has touched the lives of people around the world in 2004. -

Eurythmy the Word and Music in Movement

Eurythmy The Word and Music in Movement The time is at hand! Dance to the Rhythms of Life! 100Ye a r s Celebration 1912 – 2012 Come and join us 8 –10 June 2012 Workshops • Demonstrations Lectures • Performances Constantia Waldorf School [email protected] Starts at 18.30! 021 797 6802 Dance to the Rhythms of Life We are delighted to celebrate a 100 years of Eurythmy. We believe this art of movement, which integrates Spirit with Matter, is able to contribute in the deepest possible sense towards the healthful con- tinuation of Universal Man. 2 100Ye a r s Celebration Programme The Time is at Hand! Free Entrance (donations welcome). Refreshments available on sale. Friday, 8th June Saturday, 9th June Sunday, 10th June 18.30 Welcome 09.00 Eurythmy ‘Prelude’ 09.00 Workshops ‘Eurythmy 1912 – 2012’ 09.30 Natalia Baker 10.15 Michael Merle and Alex Boraine: ‘Well-being in our Time’ ‘Eurythmy and the ‘A question of Identity’ 10.30 Tea six-fold Path’ 19.30 Eurythmy Performance 11.00 Workshops 11.00 Tea ‘The Time is at Hand!’ 12.30 Lunch 11.30 Eurythmy Performance Man’s Journey through 14.00 Children's Eurythmy ‘The Time is at Hand!’ the Epochs of Time Performance Man’s Journey through Interval 15.30 Tea the Epochs of Time Cello Concerto by A. Dvorák 16.00 Demonstration of Interval arranged for Piano, Flute Tone & Speech Eurythmy Cello Concerto by and Cello 17.15 Michael Merle: A. Dvorák ‘Man as a Being of the Word’ arranged for Piano, Guest Speakers: 18.15 Supper Flute and Cello Alex Boraine 19.30 Eurythmy Performance 13.30 Close Natalia Baker A Bouquet of Speech and Music Pieces – Various Artists Michael Merle Eurythmy100 years Cello `Concerto’ by Antonin Dvorák op 104 for Piano and Cello This concerto comprises three movements. -

Banks' Climate Commitment 2020

Banks’ climate commitment 2020 Insight into measurement methods and climate actions of the banking sector The Dutch financial sector (banks, pension funds, insurers and asset managers) contributes extensively to the government’s climate objectives. These climate objectives were drawn up to reduce greenhouse gas emission by 49% in 2030 compared to 1990 in a cost-effective way. More than 50 financial institutions have committed themselves to report on the climate impact of their relevant financing and investments activities from the 2020 financial year onwards. Moreover, financial institutions will announce their action plans and reduction targets that contribute to the Paris Agreement by no later than 2022. Banks have taken up the challenge energetically, both individually and as a sector. This overview presents examples of joint initiatives from the banking sector. The overview also provides examples of how different banks are already utilising measurement methods. As recently demonstrated, more than half of the financial institutions that signed the Climate Commitment already (partially) report CO2 emissions. Finally, the overview presents examples of the efforts of individual banks. 2021 will see the publication of a sector report that will provide more insight into the financial sector as a whole. Examples of joint initiatives in the banking sector • With the Sustainable Housing Sector Collective, mortgage advisers are offered a Sustainable Housing Adviser training course to better promote the importance of making people's homes sustainable. • The Climate Risk Working Group, united under the Sustainable Finance Platform, published an anthology in which they describe how they manage climate risks in their portfolios and the major insights and challenges involved. -

Triodos Bank to Join Energy Efficient Mortgage Label

PRESS RELEASE Triodos Bank to join Energy Efficient Mortgage Label Brussels, 02 July 2021 – For immediate release _____________________________ The Energy Efficient Mortgages Label is pleased to welcome Triodos Bank ( Triodos Belgium – Triodos Netherlands – Triodos Spain) as new member of the Initiative. Active in five European countries with EUR 20 bn of assets under management, Triodos Bank is a leading expert in sustainable banking. Its mission is to make money work for positive change. For many years now, the bank has been taking into consideration the carbon footprint of its loans and investments and of its own activities, publicly reporting on C02 emissions. Triodos Bank opened an energy-neutral office in 2019 in the Netherlands. Acting as a clear and transparent quality benchmark for consumers, lenders and investors, the EEM Label actively demonstrates the commitment of the financial sector to achieve European climate targets, resolutely contributing to the development of sustainable investments through Energy Efficient mortgage loans, and ensuring that the Recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic is ‘green’ and therefore brings support to the NextGenerationEU vision. Finally, the EEM Label is aligned with legal and market best practices and therefore establishes itself as a global reference from the perspective of lending institutions and institutional investors, ensuring transparency on asset portfolios and privileged access to qualitative and quantitative information. Commenting on this, EEM Label Administrator, Luca Bertalot said: “ The membership of Triodos Bank to the EEM Label is a positive signal sent by the market, that sustainable and responsible loans and investments should have a positive impact on society and the planet. -

Triodos Bank: Reset the Economy561 KB

T¬B Reset the Economy An agenda for a resilient and inclusive recovery from the global corona crisis, 28 May 2020 Contents Page Executive summary 5 1. Introduction 9 2. A health crisis rooted in our relationship with nature 11 2.1 Complex systems and their vulnerabilities 11 2.2 Human activity and contagion 11 2.3 Reflections 12 3. Coronavirus as the great unequaliser 13 3.1 Causality 13 3.2 Health inequality 13 3.3 Increasing economic inequality 13 3.4 Increasing inequality between countries 15 3.5 Post-corona equality 16 4. Buffeting the no-buffer economy 18 4.1 A severe economic crisis 18 4.2 The efficient, no-buffer economy 18 4.3 The globalised efficiency economy 20 4.4 The growth-addicted system 21 5. Crisis management: supporting the economy now 22 5.1 The responses of governments and central banks 22 5.2 More is needed 24 5.3 The response of civil society and finance: chains of solidarity 27 6. Building blocks for a resilient and inclusive recovery 28 6.1 Redefine: working out what matters most 29 6.2 Revalue: mixed economy and public values 31 6.3 Redesign: open, circular and diverse markets 32 7. A concrete agenda for the recovery 34 7.1 Redefine: working out what matters most 35 7.2 Revalue: mixed economy and public values 36 7.3 Redesign: open, circular and diverse markets 37 8. The role of finance and money in the recovery 39 8.1 Redefine: all finance is impact finance 39 8.2 Revalue: equity instead of debt 40 8.3 Redesign: changing the financial system 42 8.4 Conscious choices, resilient finance 42 Sources 44 3 Address Nieuweroordweg 1, Zeist PO Box 55 3700 AB Zeist, The Netherlands Telephone +31 (0)30 693 65 00 www.triodos.com Triodos Bank is actively engaged in promoting Production value-based banking communities in the An agenda for a resilient and inclusive recovery from Netherlands and internationally. -

Steiner Academy Bristol

STEINER ACADEMY BRISTOL Free Schools in 2014 Application form Mainstream and 16-19 Free Schools Application checklist Checklist: Sections A-H of your application Yes No 1. You have established a company limited by guarantee. 2. You have provided information on all of the following areas: Section A: Applicant details – including signed declaration Section B: Outline of the school Section C: Education vision Section D: Education plan Section E: Evidence of demand Section F: Capacity and capability Section G: Initial costs and financial viability Section H: Premises 3. This information is provided in A4 format using Arial font, minimum 12 font size, includes page numbers and is no more than 150 pages in total. 4. You have completed two financial plans using the financial template spreadsheet. 5. Independent schools only: you have provided a link to the most recent inspection report. 6. Independent schools only: you have provided a copy of the last two years’ audited financial statements or equivalent. 7. All relevant information relating to Sections A-H of your application has been emailed to [email protected] between 9am on 17 December 2012 and 6pm on 4 January 2013 and the email is no more than 10 MB in size. 8. Two hard copies of the application have been sent by ‘Recorded Signed For’ post to: Free Schools Applications Team, Department for Education, 3rd Floor, Sanctuary Buildings, Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3BT. Checklist: Section I of your application 9. A copy of Section A of the form and as many copies of the Section I Personal Information form as there are members and directors have been sent by ‘Recorded Signed For’ post to: Due Diligence Team, Department for Education, 4th Floor, Sanctuary Buildings, Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3BT, between 9am on 17 December 2012 and 6pm on 4 January 2013. -

European SRI Transparency Code Triodos Impact Mixed Funds June 2021

European SRI Transparency Code Triodos Impact Mixed Funds June 2021 1 Statement of Commitment Sustainable and Responsible Investing is an essential part of the strategic positioning and behaviour of Triodos Investment Management B.V., a 100% subsidiary of Triodos Bank and responsible for managing the Triodos investment funds. We have been involved in SRI since 1996 and support the European SRI Transparency Code. This is our eleventh statement of commitment and covers the period June 2021 to June 2022. Our full response to the European SRI Transparency Code can be found below and is available on our website www.triodos-im.com. Compliance with the Transparency Code Triodos Investment Management B.V. (Triodos IM) is committed to transparency and we believe that we are as transparent as possible within the regulatory and competitive environments that exist in the countries in which we operate. Triodos IM meets the full recommendations of the European SRI Transparency Code for its Triodos Global Equities Impact Fund, Triodos Pioneer Impact Fund, Triodos Euro Bond Impact Fund, Triodos Impact Mixed Funds and Triodos Sterling Bond Impact Fund. 2 Table of Contents Statement of Commitment .................................................................................................................................... 2 Compliance with the Transparency Code ............................................................................................................. 2 1. List of funds covered by the Code .................................................................. -

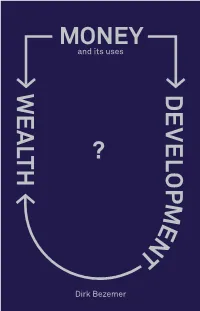

And Its Uses Dirk Bezemer

and its uses Dirk Bezemer Published on the occasion of the farewell reception of Pierre Aeby as Chief Financial Officer (CFO) and member of the Executive Board of Triodos Bank. 2 Money and its uses: development or wealth? Dirk Bezemer Biography Pierre Aeby Dirk Bezemer Pierre Aeby (1956) was CFO and Dirk Bezemer (1971) is Professor in the Executive Board member of Triodos Economics of International Financial Bank NV between 2000 and 2019. Development at the University of His first role, in 1980, was at the Groningen. He developed a research European Credit Bank in Brussels. programme on the consequences of This was followed by fourteen years financial development for financial with the Belgian Generale Bank (now fragility and for equitable and BNP Paribas Fortis). Pierre joined sustainable growth. He published Triodos Bank in 1998 as Managing widely on economic development, Director of Triodos Bank Belgium. on economic methodology, and on During more than two decades with money, credit and financial instability. the bank, as a consistently strong Dirk regularly engages in policy advocate for sustainable economic discussions and contributes to the development, he has helped build its public debate. He is a member of international presence and embed the Sustainable Finance Lab and he the Triodos ethos of consciously writes an economics column for dealing with money. De Groene Amsterdammer. 4 Table of Contents Biography 4 Preface 7 Introduction 11 Features Part 1 1 Money: some history 15 2 Money is a means of settlement 21 3 Money is a social -

Banking to Make a Difference

Banking to make a difference A preliminary research paper on the business models of the founding member banks of the Global Alliance for Banking on Values June 2009 Christophe Scheire Sofie De Maertelaere Artevelde University College, in cooperation with Global Alliance for Banking on Values and supported by European Social Fund Table of Contents Chapter 1 Quick scan research on the characteristics of 12 member banks1 of the Global Alliance for Banking on Values ...................................................... 5 1.1. Description and analysis of (the diversity) of banking practices and banking activities ................................................................................................... 5 1.2. Description and analysis of the structure of the banks .................................... 15 1.3. Description and analysis of the economic performance of these banks .............. 18 Chapter 2 Case study on the business models adopted by four Global Alliance members ............................................................................................ 27 2.1. Introducing the four banks ......................................................................... 27 2.2. Defining the business models applied by the selection of banks ....................... 29 2.3. Conclusion ............................................................................................... 40 Executive summary ......................................................................................... 41 Credits ........................................................................................................... -

Zsolnai TABEC Paper Final.Pdf

Laszlo Zsolnai Business Ethics Center Corvinus University of Budapest Materialistic versus Non-materialistic Value-orientation in Management* The Occupy Wall Street and other anti-globalization movement show a dramatic loss of confidence in mainstream business. Big businesses lost credibility and trust worldwide. The basic assumptions of business management became questionable. 1 The Materialistic Management Model The dominant management model of today's business is based on a materialistic conception of man. Human beings are considered as body-mind encapsulated egos having only materialistic desires and motivation. This kind of creature is modeled as Homo Oeconomicus in economics and business. Homo Oeconomicus represents an individual being which seeks to maximize his or her self- interest. He or she is interested only in material utility defined in the terms of money. The Materialistic Management Model uses money-driven extrinsic motivation and measures success by the generated profit. The economic and financial crisis of 2008-2009 has deepened our understanding of the problems of mainstream businesses which base their activities on unlimited greed and the “enrich yourself” mentality. ---------------------------------- * The paper was completed when the author was Visiting International Scholar at the Jepson School of Leadership Studies, University of Richmond , Virginia, USA in February – May 2013. 1 There are two distinct but interrelated problems with the underlying assumptions of the materialistic management model. One deals with profit as the sole measure of success of economic activities while the other deals with money as the main motivation of economic activities. (Zsolnai, L. 2011) Profit as measure of success Profit is inadequate as the sole measure of the success of economic activities. -

A New Prospectus in Respect of Depository Receipts of Triodos Bank Is Published Which Will Replace the Current Prospectus

DR Prospectus 24 September 2020 STICHTING ADMINISTRATIEKANTOOR AANDELEN TRIODOS BANK (established in The Netherlands as a foundation, having its corporate seat in Zeist, The Netherlands) Offering of up to 3,000,000 new depository receipts for ordinary shares with a nominal value of EUR 50 each in TRIODOS BANK N.V. (incorporated in The Netherlands as a public company with limited liability, having its corporate seat in Zeist, The Netherlands) Triodos Bank N.V. (Triodos Bank) is offering through Stichting Administratiekantoor Aandelen Triodos Bank (the Issuer) up to 3,000,000 depository receipts in registered form (the Depository Receipts) in respect of ordinary shares in registered form with a nominal value of EUR 50 each (the Shares) in the capital of Triodos Bank (the Offering). The Offering consists of a public offering being made to the public in Belgium, Germany, The Netherlands and Spain. This document (the Prospectus) constitutes a prospectus for the purposes of the Regulation (EU) 2017/1129 (the Prospectus Regulation) and has been prepared in accordance with this Regulation and the rules thereunder. This Prospectus has been approved by and filed with The Netherlands Authority for the Financial Markets (Autoriteit Financiële Markten, the AFM). The AFM only approves this Prospectus as meeting the standards of completeness, comprehensibility and consistency imposed by the Prospectus Regulation. Such approval should not be considered as an endorsement of the quality of the Depository Receipts and of the Issuer or Triodos Bank that are the subject of this Prospectus. Investors should make their own assessment as to the suitability of investing in the Depository Receipts. -

General Anthroposophical Society Anthroposophy Worldwide 6/18

General Anthroposophical Society Anthroposophy Worldwide 6/18 ■ antroposophical society June 2018 • N° 6 General Anthroposophical Society Anthroposophical Society 1 Contact by email? May we contact you by email? 2018 Annual Conference and agm 4 Switzerland: Respecting, understanding and Dear Members, implementing the results @ 5 Switzerland: Open discussion Anthroposophy Worldwide will take a new 6 Netherlands: A question step in 2019 and the General Anthroposophi- This shared awareness and participation is of perspective cal Society will make another attempt at to become possible for many more members 7 More members’ voices reaching as many members as possible in the future! 9 Meeting of all treasurers 13 Annual motif: The second electronically – wherever this is feasible. It can be achieved today via email and Foundation Stone For this we will need your help. the internet which means that there will be rhythm as a seed As an association of people of many no expensive printing and dispatching and 15 Membership News coun t ries, languages and cultural regions the most remote places can be reached be- the Anthroposophical Society and many cause most members have internet access. Anthroposophy Worldwide 2 Ireland: conference institutions inspired by Rudolf Steiner have We will make sure, however, that printed «Exploring Hibernia» spread across the whole world. To create a versions go out to those who wish for this newsletter for as many of the more than (subject to a charge). Goetheanum 40,000 members as possible and promote 3 Leadership: Second a shared awareness regarding questions of Fast and direct letter to the Members anthroposophy requires multilingualism In order to reach you quickly and directly 12 Leadership: World Goetheanum Association founded and the use of emails and the internet.