Port Tobacco River Watershed Characterization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for The Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds Prepared By: Scott M. Strickland Virginia R. Busby Julia A. King With Contributions From: Francis Gray • Diana Harley • Mervin Savoy • Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland Mark Tayac • Piscataway Indian Nation Joan Watson • Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes Rico Newman • Barry Wilson • Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians Hope Butler • Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians Prepared For: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, Maryland St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland November 2015 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this project was to identify and represent the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman creek watersheds on the north shore of the Potomac River in Charles and Prince George’s counties, Maryland. The project was undertaken as an initiative of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay office, which supports and manages the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. One of the goals of the Captain John Smith Trail is to interpret Native life in the Middle Atlantic in the early years of colonization by Europeans. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept, developed as an important tool for identifying Native landscapes, has been incorporated into the Smith Trail’s Comprehensive Management Plan in an effort to identify Native communities along the trail as they existed in the early17th century and as they exist today. Identifying ICLs along the Smith Trail serves land and cultural conservation, education, historic preservation, and economic development goals. Identifying ICLs empowers descendant indigenous communities to participate fully in achieving these goals. -

Popes Creek Trail Concept Presented

Popes Creek Trail concept presented Posted by TBN_Charles On 06/22/2017 La Plata, MD - The Pope’s Creek Rail Trail is moving forward. Eileen Minnick, Charles County director of recreation, told the Charles County Commissioners Tuesday, June 20 that barring any hiccups along the way, construction on the new trail could begin as early as next summer. In January 2014, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources was awarded a $1 million federal grant to preserve 220 acres of the Popes Creek watershed. The thought was to establish a new rail trail along the abandoned Popes Creek rail bed, a distance of some two miles. “One of the goals of the county recreation and parks and tourism is water access,” said Parks Director Jon Snow. “It’s a real challenge to get waterfront access.” Snow said the county is adding boat ramps and kayak launches at Port Tobacco River Park and Chapel Point. “Everyone in Charles County wants it, but not everyone is a boater,” Snow said. “But they still want water access. These projects will do a really good job of providing that. “Popes Creek is one of our best opportunities for waterfront access,” he added. “We’ve got a really good opportunity to create a water access venue on and off the water. Steve Engle of Vista Design Inc. outlined a conceptual plan for the trail, which includes an elevated observation platform over the Potomac River and a possible museum at the site of the old Southern Maryland Electric Cooperative power plant at Popes Creek, built in 1938. -

Title 26 Department of the Environment, Subtitle 08 Water

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 2 26.08.01.00 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapter 01 General Authority: Environment Article, §§9-313—9-316, 9-319, 9-320, 9-325, 9-327, and 9-328, Annotated Code of Maryland 3 26.08.01.01 .01 Definitions. A. General. (1) The following definitions describe the meaning of terms used in the water quality and water pollution control regulations of the Department of the Environment (COMAR 26.08.01—26.08.04). (2) The terms "discharge", "discharge permit", "disposal system", "effluent limitation", "industrial user", "national pollutant discharge elimination system", "person", "pollutant", "pollution", "publicly owned treatment works", and "waters of this State" are defined in the Environment Article, §§1-101, 9-101, and 9-301, Annotated Code of Maryland. The definitions for these terms are provided below as a convenience, but persons affected by the Department's water quality and water pollution control regulations should be aware that these definitions are subject to amendment by the General Assembly. B. Terms Defined. (1) "Acute toxicity" means the capacity or potential of a substance to cause the onset of deleterious effects in living organisms over a short-term exposure as determined by the Department. -

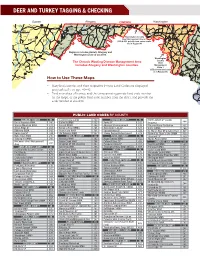

Deer and Turkey Tagging & Checking

DEER AND TURKEY TAGGING & CHECKING Garrett Allegany CWDMA Washington Frederick Carroll Baltimore Harford Lineboro Maryland Line Cardiff Finzel 47 Ellerlise Pen Mar Norrisville 24 Whiteford ysers 669 40 Ringgold Harney Freeland 165 Asher Youghiogheny 40 Ke 40 ALT Piney Groev ALT 68 615 81 11 Emmitsburg 86 ge Grantsville Barrellville 220 Creek Fairview 494 Cearfoss 136 136 Glade River aLke Rid 546 Mt. avSage Flintstone 40 Cascade Sabillasville 624 Prospect 68 ALT 36 itts 231 40 Hancock 57 418 Melrose 439 Harkins Corriganville v Harvey 144 194 Eklo Pylesville 623 E Aleias Bentley Selbysport 40 36 tone Maugansville 550 419410 Silver Run 45 68 Pratt 68 Mills 60 Leitersburg Deep Run Middletown Springs 23 42 68 64 270 496 Millers Shane 646 Zilhman 40 251 Fountain Head Lantz Drybranch 543 230 ALT Exline P 58 62 Prettyboy Friendsville 638 40 o 70 St. aulsP Union Mills Bachman Street t Clear 63 491 Manchester Dublin 40 o Church mithsburg Taneytown Mills Resevoir 1 Aviltn o Eckhart Mines Cumberland Rush m Spring W ilson S Motters 310 165 210 LaVale a Indian 15 97 Rayville 83 440 Frostburg Glarysville 233 c HagerstownChewsville 30 er Springs Cavetown n R 40 70 Huyett Parkton Shawsville Federal r Cre Ady Darlingto iv 219 New Little 250 iv Cedar 76 140 Dee ek R Ridgeley Twiggtown e 68 64 311 Hill Germany 40 Orleans r Pinesburg Keysville Mt. leasP ant Rocks 161 68 Lawn 77 Greenmont 25 Blackhorse 55 White Hall Elder Accident Midlothian Potomac 51 Pumkin Big pringS Thurmont 194 23 Center 56 11 27 Weisburg Jarrettsville 136 495 936 Vale Park Washington -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

Report of Investigations 71 (Pdf, 4.8

Department of Natural Resources Resource Assessment Service MARYLAND GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Emery T. Cleaves, Director REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS NO. 71 A STRATEGY FOR A STREAM-GAGING NETWORK IN MARYLAND by Emery T. Cleaves, State Geologist and Director, Maryland Geological Survey and Edward J. Doheny, Hydrologist, U.S. Geological Survey Prepared for the Maryland Water Monitoring Council in cooperation with the Stream-Gage Committee 2000 Parris N. Glendening Governor Kathleen Kennedy Townsend Lieutenant Governor Sarah Taylor-Rogers Secretary Stanley K. Arthur Deputy Secretary MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 580 Taylor Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21401 General DNR Public Information Number: 1-877-620-8DNR http://www.dnr.state.md.us MARYLAND GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 2300 St. Paul Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218 (410) 554-5500 http://mgs.dnr.md.gov The facilities and services of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion, sex, age, national origin, or physical or mental disability. COMMISSION OF THE MARYLAND GEOLOGICAL SURVEY M. GORDON WOLMAN, CHAIRMAN F. PIERCE LINAWEAVER ROBERT W. RIDKY JAMES B. STRIBLING CONTENTS Page Executive summary.........................................................................................................................................................1 Why stream gages?.........................................................................................................................................................4 Introduction............................................................................................................................................................4 -

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for The Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds Prepared By: Scott M. Strickland Virginia R. Busby Julia A. King With Contributions From: Francis Gray, Diana Harley, Mervin Savoy, Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland Mark Tayac, Piscataway Indian Nation Joan Watson, Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes Rico Newman, Barry Wilson, Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians Hope Butler, Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians Prepared For: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, Maryland St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland November 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this project was to identify and represent the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman creek watersheds on the north shore of the Potomac River in Charles and Prince George’s counties, Maryland. The project was undertaken as an initiative of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay office, which supports and manages the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. One of the goals of the Captain John Smith Trail is to interpret Native life in the Middle Atlantic in the early years of colonization by Europeans. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept, developed as an important tool for identifying Native landscapes, has been incorporated into the Smith Trail’s Comprehensive Management Plan in an effort to identify Native communities along the trail as they existed in the early17th century and as they exist today. Identifying ICLs along the Smith Trail serves land and cultural conservation, education, historic preservation, and economic development goals. Identifying ICLs empowers descendant indigenous communities to participate fully in achieving these goals. -

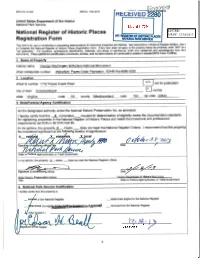

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NOV 0 ·~ 2013 National Register of Historic Places NAT. Re018TiR OF HISTORIC PlACES Registration Form NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name George Washington Birthplace National Monument other names/site number Wakefield. Popes Creek Plantation , VDHR File #096-0026 2. Location 1732 Popes Creek Road not for publication street & number L-----' city or town Colonial Beach ~ vicinity state Vir inia code VA county Westmoreland code _ _;_:19'--=-3- zip code -"'2=2:....;.4"""43.;;...._ ___ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _!__nomination_ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property .K._ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: x_ b state ' Ide "x n J.VIA.rVI In my opinion, the property .x..._ meets_ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Directions to Mattawoman Creek Mattingly Avenue Park - Indian Head, MD 20640

Atlantic Canoe & Kayak Company 13600 King Charles Terrace Fort Washington, Maryland 20744 301.292. 6455 or 703.838.9072 [email protected] www.atlantickayak.com Directions to Mattawoman Creek Mattingly Avenue Park - Indian Head, MD 20640 From the Beltway (495): Take Exit 3 to Indian Head Highway (Route 210) South. Continue approximately 20 miles. Turn left on Mattingly Avenue (just before the military base) and continue approximately 0.6 miles to the park. Please park at the top of the hill in the lot on the left. If the lot is full, you can park on Jennifer Drive, just up from the park. We are located in the building at the bottom of the hill near the boat ramps. Checklist of What to Bring Drinking water or spot drink (plenty) Snack or lunch (waterproof) Sunscreen Shoes you don’t mind getting wet or muddy (aqua shoes or booties) Hat or visor for sun protection and/or warmth Sunglasses with retaining strap (if you want to keep them) Nylon shorts are preferable to cotton—they dry more quickly T-shirt or tank top for warm weather Quick dry shirt for cooler weather Fleece or wool and windbreaker for cooler weather Rain gear if rain is expected Change of clothes and a towel (just in case—leave in car) Binoculars, camera, nature books, if desired Date: RENTAL Single Recreational Kayak Depart Time: RECORD Tandem Kayak Mattawoman Creek Return Time: Name, printed legibly: ______________________________________________________ CELL PHONE ON THE WATER: _______________________________ Home Address: _____________________________________________________________ -

Port Tobacco River Watershed Assessment Summary

LOWER PATUXENT RIVER WATERSHED ASSESSMENT JUNE | 2016 PREPARED FOR Charles County Department of Planning and Growth Management Watershed Protection and Restoration Program 200 Baltimore St., La Plata, MD 20646 PREPARED BY KCI TECHNOLOGIES, INC. 936 RIDGEBROOK ROAD SPARKS, MD 21152 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Lower Patuxent Watershed Assessment was a collaborative effort between Coastal Resources, Inc., KCI Technologies, Inc. and Charles County Department of Planning and Growth Management. The resulting report was authored by the following individuals from KCI Technologies, Inc. and Charles County. Susanna Brellis | KCI Technologies, Inc. Megan Crunkleton | KCI Technologies, Inc. Colin Hill | KCI Technologies, Inc. Bill Frost | KCI Technologies, Inc. Michael Pieper | KCI Technologies, Inc. James Tomlinson | KCI Technologies, Inc. Charles Rice | Charles County P&GM Karen Wiggen | Charles County P&GM Lower Patuxent River Watershed Assessment TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 5 1.1 Background ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 5 1.2 Watershed description --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 1.3 Previous Watershed studies and Assessments -------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.4 Goals --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.4.1 Watershed -

Watersheds.Pdf

Watershed Code Watershed Name 02130705 Aberdeen Proving Ground 02140205 Anacostia River 02140502 Antietam Creek 02130102 Assawoman Bay 02130703 Atkisson Reservoir 02130101 Atlantic Ocean 02130604 Back Creek 02130901 Back River 02130903 Baltimore Harbor 02130207 Big Annemessex River 02130606 Big Elk Creek 02130803 Bird River 02130902 Bodkin Creek 02130602 Bohemia River 02140104 Breton Bay 02131108 Brighton Dam 02120205 Broad Creek 02130701 Bush River 02130704 Bynum Run 02140207 Cabin John Creek 05020204 Casselman River 02140305 Catoctin Creek 02130106 Chincoteague Bay 02130607 Christina River 02050301 Conewago Creek 02140504 Conococheague Creek 02120204 Conowingo Dam Susq R 02130507 Corsica River 05020203 Deep Creek Lake 02120202 Deer Creek 02130204 Dividing Creek 02140304 Double Pipe Creek 02130501 Eastern Bay 02141002 Evitts Creek 02140511 Fifteen Mile Creek 02130307 Fishing Bay 02130609 Furnace Bay 02141004 Georges Creek 02140107 Gilbert Swamp 02130801 Gunpowder River 02130905 Gwynns Falls 02130401 Honga River 02130103 Isle of Wight Bay 02130904 Jones Falls 02130511 Kent Island Bay 02130504 Kent Narrows 02120201 L Susquehanna River 02130506 Langford Creek 02130907 Liberty Reservoir 02140506 Licking Creek 02130402 Little Choptank 02140505 Little Conococheague 02130605 Little Elk Creek 02130804 Little Gunpowder Falls 02131105 Little Patuxent River 02140509 Little Tonoloway Creek 05020202 Little Youghiogheny R 02130805 Loch Raven Reservoir 02139998 Lower Chesapeake Bay 02130505 Lower Chester River 02130403 Lower Choptank 02130601 Lower -

Chesapeake Bay Trust Maryland Outdoor Spaces - Legislator Favorites 1/21/21

Chesapeake Bay Trust Maryland Outdoor Spaces - Legislator Favorites 1/21/21 On January 21, 2021, more than 60 legislators attended the Chesapeake Bay Trust’s virtual legislative reception. They were invited to share some of their favorite outdoor spots in their districts and throughout Maryland. Their contributions were so wonderful that we were asked to compile them and send them to attendees. As Senate President Bill Ferguson said, “Our parks are those spaces that bring Marylanders together to get that fundamental belief in love of family, of friends, of each other.” “Our 6,400 parks and green spaces are a great way to boost your mental and overall health” added House Speaker Adrienne Jones.” Maryland Department of Natural Resources Secretary Jeanne Haddaway-Riccio reminded us all how diverse Maryland is, and we see this in the list of favorite spots below. Below is YOUR list! The sites on the list below are not exhaustive, but were those suggested by legislators and guests present that evening as places they visit to get outdoors and feel refreshed and recharged. The entries include a word or two about the site, at times thoughts from your colleagues, the name of the legislator suggesting the site, and a website for more information. You can visit by yourself or call up your colleagues and ask for a personal tour! Anne Arundel County B&A Trail, great for walking, biking, rollerblading, and more, stretches from Boulters Way in Annapolis to Dorsey Road in Glen Burnie, Maryland. The Earleigh Heights Ranger Station (ca. 1889) is located in Severna Park with parking available on the premises.