Power Over Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feminist Mobilization and the Abortion Debate in Latin America: Lessons from Argentina

Feminist Mobilization and the Abortion Debate in Latin America: Lessons from Argentina Mariela Daby Reed College [email protected] Mason Moseley West Virginia University [email protected] When Argentine President Mauricio Macri announced in March 2018 that he supported a “responsible and mature” national debate regarding the decriminalization of abortion, it took many by surprise. In a Catholic country with a center-right government, in which public opinion regarding abortion had hardly moved in decades—why would the abortion debate surface in Argentina when it did? Our answer is grounded in the social movements literature, as we argue that the organizational framework necessary for growing the decriminalization movement was already built by an emergent feminist movement of unprecedented scope and influence: Ni Una Menos. Through expanding the movement’s social justice frame from gender violence to encompass abortion rights, feminist social movements were able to change public opinion and expand the scope of debate, making salient an issue that had long been politically untouchable. We marshal evidence from multiple surveys carried out before, during, and after the abortion debate and in-depth interviews to shed light on the sources of abortion rights movements in unlikely contexts. When Argentine President Mauricio Macri announced in March 2018 that he supported a “responsible and mature” national debate regarding the decriminalization of abortion, many were surprised. After all, in 2015 he was the first conservative president elected in Argentina in over a decade, and no debate had emerged under prior center-left governments. Moreover, Argentina is a Catholic country, which has if anything seen an uptick in religiosity over the past decade, and little recent movement in public support for abortion rights preceding Macri’s announcement. -

The Epidemiology of Abortion and Its Prevention in Chile, 79(5) Rev

Gene Gene Start Gene End Motif Start Motif End Motif Strand Exon Start Exon End HS Start HS End Distance NLGN4X 5808082 6146706 5821352 5821364 gtggccacggcgg ‑ 5821117 5821907 5811910 5813910 7442 AFF2 147582138 148082193 148048477 148048489 ccaccatcacctc + 148048319 148048609 148036319 148040319 8158 NLGN3 70364680 70391051 70386983 70386995 gtggatatggtgg + 70386860 70387650 70371089 70377089 9894 MECP2 153287263 153363188 153296166 153296178 gtggtgatggtgg ‑ 153295685 153296901 153306976 153308976 10798 FRMPD4 12156584 12742642 12739916 12739928 ccaccatggccgc + 12738647 12742642 12721454 12727454 12462 PHF8 53963112 54071569 54012352 54012364 ccaccatgtcctc ‑ 54012339 54012382 54025089 54033089 12725 RAB39B 154487525 154493852 154493567 154493579 cctccatggccgc ‑ 154493358 154493852 154478566 154480566 13001 FRMPD4 12156584 12742642 12736309 12736321 ggggcaagggagg + 12735619 12736909 12721454 12727454 14867 GRPR 16141423 16171641 16170710 16170722 cctccgtggccac + 16170378 16171641 16208454 16211454 37732 AFF2 147582138 148082193 148079262 148079274 cccccgtcaccac + 148072740 148082193 148036319 148040319 38943 SH3KBP1 19552082 19905744 19564111 19564123 cctccttatcctc ‑ 19564039 19564168 19610454 19614454 46331 PDZD4 153067622 153096003 153070331 153070343 cccccttctcctc ‑ 153067622 153070355 153013976 153018976 51355 SLC6A8 152953751 152962048 152960611 152960623 ccaccctgacccc + 152960528 152962048 153013976 153018976 53353 FMR1 146993468 147032647 147026533 147026545 gaggacaaggagg + 147026463 147026571 147083193 147085193 56648 HNRNPH2 -

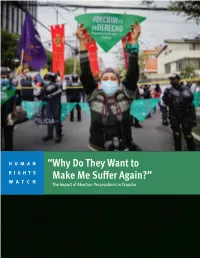

“Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” the Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador

HUMAN “Why Do They Want to RIGHTS WATCH Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ....................................................................................................... 8 To the Presidency ................................................................................................................... -

Should Abortion Be Decriminalized in Korea?

한국의료윤리학회지 제21권제2호(통권 제55호) : 129-142 ⓒ한국의료윤리학회, 2018년 6월 Korean J Med Ethics 21(2) : 129-142 ⓒ The Korean Society for Medical Ethics, June 2018 pISSN 2005-8284 eISSN 2234-3598 투고일: 2018년 5월 28일, 심사일: 2018년 5월 30일, 게재확정일: 2018년 6월 13일 Should Abortion Be Decriminalized in Korea? John McGuire* I. INTRODUCTION petition to the Court, with over 1 million signa- tures on it, urging the Court not to decriminal- The Constitutional Court of Korea is currently ize abortion, Korean women’s groups, such as reviewing a case brought by a Korean doctor who Womenlink and Korea Women’s Hot Line, have is challenging the constitutionality of Korea’s been actively campaigning against the current laws criminal laws on abortion. Not surprisingly, the [2,3]. And although a group of almost 100 pro-life case has exposed deep divisions within Korean so- university professors, have written to the court in ciety and has also attracted considerable attention support of the existing laws on abortion, another from interested groups abroad. While the Korean group of over 100 researchers from the fields of Ministry of Defense has spoken out in favor of the bioethics, philosophy, and theology released a country’s existing abortion laws, the Ministry of public statement calling for the abolition of those Gender Equality has written to the Constitutional laws [1,4]. The international NGO Human Rights Court in opposition to the existing laws, claiming Watch has also weighed into the controversy by that the laws prohibiting abortion are being used submitting an amicus brief urging the Court to against women and are inconsistent with Korea’s decriminalize abortion and ensure safe and legal international treaty obligations, including those access for women in need of abortions [5]. -

Life and Learning Xix

LIFE AND LEARNING XIX PROCEEDINGS OF THE NINETEENTH UNIVERSITY FACULTY FOR LIFE CONFERENCE at THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS SCHOOL OF LAW MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA 2009 edited by Joseph W. Koterski, S.J. KOTERSKI LIFE AND LEARNING XIX UFL University Faculty for Life University Faculty for Life was founded in 1989 to promote research, dialogue, and publication among faculty members who respect the value of human life from its inception to natural death, and to provide academic support for the pro-life position. Respect for life is especially endangered by the current cultural forces seeking to legitimize such practices as abortion, infanticide, euthanasia, and physician-assisted suicide. These topics are controversial, but we believe that they are too important to be resolved by the shouting, the news-bites, and the slogans that often dominate popular presentation of these issues. Because we believe that the evidence is on our side, we would like to assure a hearing for these views in the academic community. The issues of abortion, infanticide, and euthanasia have many dimensions–political, social, legal, medical, biological, psychological, ethical, and religious. Accordingly, we hope to promote an inter-disciplinary forum in which such issues can be discussed among scholars. We believe that by talking with one another we may better understand the values we share and become better informed in our expression and defense of them. We are distressed that the media often portray those favoring the value of human life as mindless zealots acting out of sectarian bias. We hope that our presence will change that image. We also believe that academicians united on these issues can encourage others to speak out for human life in their own schools and communities. -

Induced Abortion in Chile

In Brief Induced Abortion in Chile Chile is one of a small handful of countries worldwide that Abortion-related deaths and injuries appear to have declined dramatically prohibit induced abortion under any circumstance, including In the 1960s, many Chilean women if a woman’s life is at risk. The longstanding ban, which undergoing unsafe abortions died as a result, or suffered serious short- or long- runs counter to Chile’s stated commitment to international term health complications for which they women’s rights treaties, faces a robust challenge in the did not receive the medical treatment they needed.9 In 1960, there were 294 form of a recent bill proposed by the government of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births,10 and one-third of these deaths were at- President Bachelet that would allow the procedure under tributable to unsafe abortion.11 One in limited circumstances. Yet informed debate on the topic is five hospital beds in obstetric depart- ments were occupied by women receiving hindered by the lack of data on the incidence and context of postabortion treatment. clandestine induced abortion. Chile’s maternal mortality ratio fell to 55 deaths per 100,000 live births by In every country, regardless of the legal No data exist on the characteristics of 1990, and to 22 by 2013.12 The precise status of induced abortion, some women women obtaining abortions in Chile, nor contribution of unsafe induced abortion experiencing an unintended pregnancy on their reasons for doing so. As one to overall maternal mortality is unclear, turn to abortion to end it.1 Chile is no researcher points out, “we do not know… but experts agree that far fewer deaths exception to this worldwide pattern. -

Bibliography of Sexuality Studies in Latin America

Bibliography of Sexuality Studies in Latin America In 1997 Donna J. Guy and I published a bibliography of sexuality studies on Latin America in our edited book Sex and Sexuality in Latin America (New York University Press, 1997), including studies in a wide variety of fields. This bibliography was updated for the Spanish edition of that book, Sexo y sexualidades en América Latina (Paidos, Buenos Aires, 1998); that version included a number of items that had come to our attention after we turned in the book to NYU. Interestingly, the number of publications in Latin America (and in Spanish and Portuguese) increased in that brief period, and continues to increase. Adán Griego has added his own bibliography and has agreed to maintain it and keep it current. The bibliography that follows is based on the previous ones but has the advantage of not being fixed in time. —— Daniel Balderston, 1999. This bibliographic list is organized alphabetically by author, or by title in a few cases where no specific author appears. Select the initial letter of the author or the title of the work you are looking for or simply scroll down the list. Please send corrections, additions and comments to: [email protected] A A las orillas de Lesbos. Narrativa lésbica. Lima: MHOL, 1997. Abad, Erika Gisela. "¿La Voz de Quién?" Diálogo, No.12, (Summer 2009): 28. Abdalla, Fernanda Tavares de Mello and Nichiata, Lúcia Yasuko Izumi. A Abertura da privacidade e o sigilo das informações sobre o HIV/Aids das mulheres atendidas pelo Programa Saúde da Família no município de São Paulo, Brasil. -

Amnesty International Report 2014/15 the State of the World's Human Rights

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL OF THE WORLD’S HUMAN RIGHTS THE STATE REPORT 2014/15 AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL REPORT 2014/15 THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S HUMAN RIGHTS The Amnesty International Report 2014/15 documents the state of human rights in 160 countries and territories during 2014. Some key events from 2013 are also reported. While 2014 saw violent conflict and the failure of many governments to safeguard the rights and safety of civilians, significant progress was also witnessed in the safeguarding and securing of certain human rights. Key anniversaries, including the commemoration of the Bhopal gas leak in 1984 and the Rwanda genocide in 1994, as well as reflections on 30 years since the adoption of the UN Convention against Torture, reminded us that while leaps forward have been made, there is still work to be done to ensure justice for victims and survivors of grave abuses. AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL This report also celebrates those who stand up REPORT 2014/15 for human rights across the world, often in difficult and dangerous circumstances. It represents Amnesty International’s key concerns throughout 2014/15 the world, and is essential reading for policy- THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S makers, activists and anyone with an interest in human rights. HUMAN RIGHTS Work with us at amnesty.org AIR_2014/15_cover_final.indd All Pages 23/01/2015 15:04 AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. -

Aesthetics After Finitude Anamnesis Anamnesis Means Remembrance Or Reminiscence, the Collection and Re- Collection of What Has Been Lost, Forgotten, Or Effaced

Aesthetics After Finitude Anamnesis Anamnesis means remembrance or reminiscence, the collection and re- collection of what has been lost, forgotten, or effaced. It is therefore a matter of the very old, of what has made us who we are. But anamnesis is also a work that transforms its subject, always producing something new. To recollect the old, to produce the new: that is the task of Anamnesis. a re.press series Aesthetics After Finitude Baylee Brits, Prudence Gibson and Amy Ireland, editors re.press Melbourne 2016 re.press PO Box 40, Prahran, 3181, Melbourne, Australia http://www.re-press.org © the individual contributors and re.press 2016 This work is ‘Open Access’, published under a creative commons license which means that you are free to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form whatso- ever and that you in no way alter, transform or build on the work outside of its use in normal aca- demic scholarship without express permission of the author (or their executors) and the publisher of this volume. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. For more information see the details of the creative commons licence at this website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Title: Aesthetics after finitude / Baylee Brits, Prudence Gibson and Amy Ireland, editors. ISBN: 9780980819793 (paperback) Series: Anamnesis Subjects: Aesthetics. -

Abortion Law and Policy Around the World: in Search of Decriminalization Marge Berer

HHr Health and Human Rights Journal HHR_final_logo_alone.indd 1 10/19/15 10:53 AM Abortion Law and Policy Around the World: In Search of Decriminalization marge berer Abstract The aim of this paper is to provide a panoramic view of laws and policies on abortion around the world, giving a range of country-based examples. It shows that the plethora of convoluted laws and restrictions surrounding abortion do not make any legal or public health sense. What makes abortion safe is simple and irrefutable—when it is available on the woman’s request and is universally affordable and accessible. From this perspective, few existing laws are fit for purpose. However, the road to law reform is long and difficult. In order to achieve the right to safe abortion, advocates will need to study the political, health system, legal, juridical, and socio-cultural realities surrounding existing law and policy in their countries, and decide what kind of law they want (if any). The biggest challenge is to determine what is possible to achieve, build a critical mass of support, and work together with legal experts, parliamentarians, health professionals, and women themselves to change the law—so that everyone with an unwanted pregnancy who seeks an abortion can have it, as early as possible and as late as necessary. Marge Berer is international coordinator of the International Campaign for Women’s Right to Safe Abortion, London, UK, and was the editor of Reproductive Health Matters, which she founded, from 1993 to 2015. Please address correspondence to Marge Berer. Email: [email protected]. -

Access to Abortion Reports

ACCESS TO ABORTION: An Annotated Bibliography of Reports and Scholarship Second edition (as of April 1, 2020) prepared by The International Reproductive and Sexual Health Law Program Faculty of Law, University of Toronto, Canada, 2020 http://www.law.utoronto.ca/documents/reprohealth/abortionbib.pdf Online Publication History: This edition: Access to Abortion: An Annotated Bibliography of Reports and Scholarship. “Second edition,” current to April 1 2020, published online August 31, 2020 at: http://www.law.utoronto.ca/documents/reprohealth/abortionbib.pdf Original edition: “Access to Abortion Reports: An Annotated Bibliography” (published online January 2008, slightly updated January 2009) has been moved to: http://www.law.utoronto.ca/documents/reprohealth/abortionbib2009.pdf Publisher: The International Reproductive and Sexual Health Law Program Faculty of Law, University of Toronto, 78 Queen’s Park Crescent, Toronto Canada M5S 2A5 Website Reprohealthlaw Blog Contact: reprohealth.law{at}utoronto.ca Acknowledgements: We are most grateful to Professor Joanna Erdman for founding this bibliography in 2008-9. We are also indebted to Katelyn Sheehan (LL.M.) and Sierra Farr (J.D. candidate) for expertly collecting and analyzing new resources up to April 1, 2020, and to Sierra Farr for updating the introduction to this second edition. Updates: Kindly send suggestions for the next edition of this bibliography to: Professor Joanna Erdman, MacBain Chair in Health Law and Policy, Health Law Institute, Schulich School of Law, Dalhousie University, Email: joanna.erdman{at}dal.ca ACCESS TO ABORTION: An Annotated Bibliography of Reports and Scholarship, 2020 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY: Widespread evidence indicates that abortion services remain inaccessible and inequitably available for many people despite legal entitlement.1 This is true in jurisdictions that permit abortion for specific indications (e.g. -

The Uruguayan Model for Reducing the Risk and Harm of Unsafe Abortions

Changing relationships in the health care context: the Uruguayan model for reducing the risk and harm of unsafe abortions Montevideo, Uruguay Also published in Spanish (2012) with the title: Cambio en la relación sanitaria: modelo uruguayo de educación de riesgo y daño del aborto inseguro. The Pan American Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications, in part or in full. Applications and inquiries should be addressed to Editorial Services, Entity of Knowledge Management and Communications (KMC), Pan American Health Organization, Washington, D.C., U.S.A. The Office of Gender, Diversity, and Human Rights of PAHO will be glad to provide the latest information on any changes made to the text, plans for new editions, and reprints and translations already available. © Pan American Health Organization, 2012. All rights reserved. Publications of the Pan American Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accordance with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. All rights are reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the Pan American Health Organization concerning the status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the Pan American Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.