Read Sample Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather

Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall A Thesis in the PhD Humanities Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2012 © Heather Macdougall, 2012 ABSTRACT Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2012 This dissertation investigates the history of film production in the minority language of Irish Gaelic. The objective is to determine what this history reveals about the changing roles of both the national language and national cinema in Ireland. The study of Irish- language film provides an illustrative and significant example of the participation of a minority perspective within a small national cinema. It is also illustrates the potential role of cinema in language maintenance and revitalization. Research is focused on policies and practices of filmmaking, with additional consideration given to film distribution, exhibition, and reception. Furthermore, films are analysed based on the strategies used by filmmakers to integrate the traditional Irish language with the modern medium of film, as well as their motivations for doing so. Research methods included archival work, textual analysis, personal interviews, and review of scholarly, popular, and trade publications. Case studies are offered on three movements in Irish-language film. First, the Irish- language organization Gael Linn produced documentaries in the 1950s and 1960s that promoted a strongly nationalist version of Irish history while also exacerbating the view of Irish as a “private discourse” of nationalism. Second, independent filmmaker Bob Quinn operated in the Irish-speaking area of Connemara in the 1970s; his fiction films from that era situated the regional affiliations of the language within the national context. -

Beannachtaí Na Nollaigh Christmas Blessings by Mary Mcsweeney (See Page 3) Page 2 December 2010 BOSTON IRISH Reporter Worldwide At

December 2010 VOL. 21 #12 $1.50 Boston’s hometown journal of Irish culture. Worldwide at bostonirish.com All contents copyright © 2010 Boston Neighborhood News, Inc. Beannachtaí na Nollaigh Christmas Blessings by Mary McSweeney (See Page 3) Page 2 December 2010 BOSTON IRISH RePORTeR Worldwide at www.bostonirish.com John and Diddy Cullinane, and Gerard and Marilyn Doherty, Event Co-chairs Solas Awards Dinner Friday, December 10, 2010 Seaport Hotel, Boston Cash bar reception 5:30pm Dinner 6:30pm Seats are $200 each 2010 Solas Awardees Congressman Richard Neal Robert Glassman This year, the IIC is also pleased to introduce the Humanitarian Leadership award, honoring two exceptional people, who have contributed significantly to the recovery work in Haiti, following the devastating earthquake there. Please join us in honoring Sabine St. Lot, State Street Bank Corporation, and Marie St. Fleur, Director of Intergovernmental Relations, City of Boston Sponsorship opportunities are available for this event. If you or your organization would like to make a tax-deductible contribution to the Irish Immigration Center by sponsoring the Solas Awards Dinner, or you would like to attend the event, please call Mary Kerr, Solas Awards Dinner coordinator, at 617-695-1554 or e-mail her at [email protected]. We wish to thank our generous sponsors: The Law Offices of Gerard Doherty, Eastern Bank and Insurance, Wainwright Bank, State Street Corporation, Arbella Insurance Company, Carolyn Mugar, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, Michael Buckley Worldwide at www.bostonirish.com December 2010 BOSTON IRISH RePORTeR Page 3 ON THE TOWN WITH THE BIR American Ireland Fund Honors Hospice Founder More than 1,000 guests gathered at the Westin Bos- ton Waterfront on Nov. -

Notes on Film Industry SRG, 29 May 1999

The Strategic Development of the Irish Film and Television Industry 2000-2010 Final Report of the Film Industry Strategic Review Group August 1999 1 2 CONTENTS List of Figures List of Tables Members of the Irish Film Industry Strategy Review Group..........................7 Preface...................................................................................................................9 Terms of Reference ............................................................................................10 KEY STRATEGIC ISSUES AND SUMMARY OF MAJOR RECOMMENDATIONS...................................................................................11 A. INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................12 B. KEY CONCLUSIONS....................................................................................12 C. STRATEGIC ISSUES AND MAJOR RECOMMENDATIONS...................17 MAIN REPORT .................................................................................................25 1. INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................27 2. 2010 - PREVIEW OF A “VISION OF THE FUTURE” ................................28 3. IRISH FILM’S EMERGING CAPABILITIES ..............................................30 4. PRODUCING FOR A GLOBAL MARKET...................................................35 A. The Evolution of the International Market......................................................35 B. Products and Markets ......................................................................................36 -

Managing Diversity Governance Series

MANAGING DIVERSITY GOVERNANCE SERIES overnance is the process of eff ective coordination Gwhereby an organization or a system guides itself when resources, power, and information are widely distributed. Studying governance means probing the patt ern of rights and obligations that underpins organizations and social systems; understanding how they coordinate their parallel activities and maintain their coherence; exploring the sources of dysfunction; and suggesting ways to redesign organizations whose governance is in need of repair. The Series welcomes a range of contributions—from conceptual and theoretical refl ections, ethnographic and case studies, and proceedings of conferences and symposia, to works of a very practical nature—that deal with problems or issues on the governance front. The Series publishes works both in French and in English. The Governance Series is part of the publications division of the Program on Governance and Public Management at the School of Political Studies. Nine volumes have previously been published within this series. The Program on Governance and Public Management also publishes electronic journals: the quarterly www.optimumonline.ca and the biannual www.revuegouvernance.ca Editorial Committ ee Caroline Andrew Linda Cardinal Monica Gatt inger Luc Juillet Daniel Lane Gilles Paquet (Director) MANAGING DIVERSITY Practices of Citizenship Edited by Nicholas Brown and Linda Cardinal The University of Ottawa Press Ottawa © University of Ott awa Press 2007 All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitt ed in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Table of Contents

FREEDOM OF INFORMATION A guide for the public to RTÉ’s records Freedom of Information Act, 1997 Section 15 and 16 Reference Book August 2007 Page 1 of 48 Table of Contents PREFACE.......................................................................................................... 3 SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... 3 Introduction to the Freedom of Information Act ................. 4 THE FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT (FOI ACT) ......................................... 4 INFORMATION AVAILABLE AT NO COST......................................................... 4 RECORDS AVAILABLE UNDER FOI ................................................................. 4 RECORDS EXCLUDED UNDER FOI................................................................... 4 TIME LIMIT ON GETTING INFORMATION......................................................... 5 COST OF APPLICATION .................................................................................... 5 REQUESTS........................................................................................................ 5 SEARCH AND RETRIEVAL ............................................................................... 5 RESPONSE TIME............................................................................................... 5 DESIGNATED PERSONS UNDER FOI ................................................................ 6 APPEAL........................................................................................................... -

Raidió Teilifís Éireann Annual Report & Group Financial Statements 2011 Raidió Teilifís Éireann

Raidió Teilifís ÉiReann annual RepoRT & GRoup financial sTaTemenTs 2011 Raidió TeilifíS Éireann Highlights 1 Organisation Structure 2 What We Do 3 Chairman’s Statement 4 Director-General’s Review 6 Operational Review 10 Financial Review 40 Board 46 Executive 48 Corporate Governance 50 Board Members’ Report 54 Statement of Board Members’ Responsibilities 55 Independent Auditor’s Report 56 Financial Statements 57 Accounting Policies 64 Notes forming part of the Group Financial Statements 68 Other Reporting Requirements 103 Other Statistical Information 116 Financial History 121 RTÉ’S vision is to grow the TRust of the peoplE of Ireland as IT informs, inspires, reflects and enriches their lIvES. RTÉ’S mission is to: • NuRTure and reflect the CulTural and regional diversity of All the peoplE of Ireland • Provide distinctivE programming and services of the highest quAlITy and ambition, WITH the emphasis on home production • Inform the Irish PuBlic By delIvering the best comprehensivE independent news service possiblE • ENABlE national participation in All MAjor Events Raidió Teilifís Éireann Board 51st Annual Report and Group Financial Statements for the 12 months ended 31 December 2011, presented to the Minister for Communications, Energy and Natural Resources pursuant to section 109 and 110 of the Broadcasting Act 2009. Is féidir leagan Gaeilge den Tuarascáil a íoslódáil ó www.rte.ie/about/annualreport ANNuAl REPORT & GROuP FINANCIAl STATEMENTS 2011 HiGHliGHTs Since 2008 RTÉ has reduced its operating costs by close to 20% or €86 million. RTÉ continues to be Ireland’s With quality home-produced leading provider of digital programming and the best content with the country’s acquired programming from most popular Irish owned overseas, RTÉ increased its live website, the most popular peak-time viewing share on on-demand video service RTÉ One to 30.9% in 2011. -

Comhar Leabhaircomhar | Comharóg | Comhartaighde Portráidí Na Scríbhneoirí Gaeilge

COMHAR LEABHAIRCOMHAR | COMHARÓG | COMHARTAIGHDE PORTRÁIDÍ NA SCRÍBHNEOIRÍ GAEILGE 47 HARRINGTON STREET, DUBLIN 8 Telephone: +353 – 1 – 6751922 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]. Website: www.comhar.ie; www.comhar.ie/leabhair; www.comhartaighde.ie Chairperson: Cathal Goan Business and Administration Executive: Elly Shaw Publications Executive: Caitríona Ní Dhúnáin Directors: Cormac Breathnach, An Dr Liam Mac Amhlaigh, Órla Ní Chuilleanáin, An Dr Katie Ní Loingsigh, Muireann Ní Mhóráin, Paula Ní Shlatarra, Uaitéar Ó Ciaruáin, Fiachra Ó Marcaigh PORTRÁIDÍ NA SCRÍBHNEOIRÍ GAEILGE www.portraidi.ie; [email protected]; www.facebook.com/portraidi/; @scribhneoiri Editor: Dr Liam Mac Amhlaigh Project executives: Elly Shaw & Caitríona Ní Dhúnáin Technical and design consultant: Ronan Doherty A collaborative project between COMHAR & Foras na Gaeilge www.portraidi.ie PRESS RELEASE: 16 NOVEMBER 2017 COMHAR & Foras na Gaeilge have great pleasure in making two announcements relating to the project comprising the unique book (Portráidí na Scríbhneoirí Gaeilge/Portraits of Irish-language Writers) and the vibrant website www.portraidi.ie: • the launch by Chief Executive of Foras na Gaeilge, Seán Ó Coinn, of the first series of new portraits (the 2017 list) in Stage 2 of the project; and • the public announcement of the names of the new writers (the 2017 list) who will feature in the second series of new portraits. New writers in Stage 2 Portráidí na Scríbhneoirí Gaeilge is a multi-annual, multi-stage project. In the first stage of the project, the book and website based on the current archive of portraits has been made available to the public. In the second stage of the project, new additional portraits will be added to the collection on an annual basis, so that the archive of living Irish-language writers can be made as complete as possible over time. -

Raidió Teilifís Éireann Annual Report & Group Financial Statements 2010

ANNUAL REPORT & GROUP FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2010 Title Raidió Teilifís Éireann Annual Report & Group Financial Statements 2010 1 RAIdIó TeilifíS Éireann Highlights 1 Board Members’ Report 52 Organisation Structure 2 Statement of Board Members’ Responsibilities 53 What We do 3 Independent Auditor’s Report 54 Chairman’s Statement 4 Financial Statements 55 director-General’s Review 6 Accounting Policies 62 Operational Review 10 Notes forming part of the Group Financial Statements 68 Financial Review 40 Other Reporting Requirements 99 Board at 31 december 2010 46 Other Statistical Information 105 RTÉ Executive 47 Financial History 109 Corporate Governance 48 Raidió Teilifís Éireann Board RTÉ’s mission is to: 50th Annual Report and Group Financial Statements for the 12 months ended 31 December 2010, presented to the Minister • Nurture and reflect the cultural and regional for Communications, Energy and Natural Resources pursuant to diversity of all the people of Ireland section 109 and 110 of the Broadcasting Act 2009. • Provide distinctive programming and services Is féidir leagan Gaeilge den Tuarascáil a íoslódáil ó of the highest quality and ambition, with the www.rte.ie/about/annualreport emphasis on home production • Inform the Irish public by delivering the best RTÉ’s vision is to grow the trust of the comprehensive independent news service possible people of Ireland as it informs, inspires, • Enable national participation in all major events reflects and enriches their lives. ANNUAL REPORT & GROUP FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2010 Highlights RTÉ’s Annual Operating Cost Base Excluding Depreciation and Amortisation has been reduced by over €82 million / -19% since 2008. Tipperary’s dramatic victory over Kilkenny in 2010 was enjoyed free-to-air on RTÉ Television by the highest ever TV viewership for a hurling final, peaking at 1.24 million in the final minutes. -

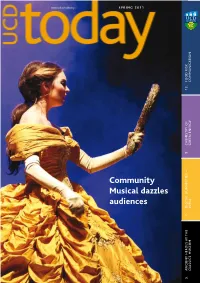

Community Musical Dazzles Audiences a L Hu Ma Nities – a I V RL a Digit

www.ucd.ie/ucdtoday audiences Musical dazzles Community SPRING 2011 5. ANCIENT HEROES AT THE 7. DIGITAL HUMAnities – 9. CHEMISTRY OF 13. FOOD RISK CLASSICS MUSEUM IVRLA GREEN ENERGY COMMUNICATION what’s inside ... New series, Art on Campus, looks at First Mellon funding for UCD – Open Days welcome families Heystaks service (co-founded ‘Newman’s Razor’ in Belfield House Iberian Book Project and students to UCD by Dr Maurice Coyle & Dr Peter 4 courtyard 10 15 18 Briggs, above) goes public UCD thanks ... Contributors: Martin Albrecht, Judith Archbold, John Baker, Veronica Barker, Danielle Barron, Marc Caball, Rose Cotter, Mary Daly, Steve Davis, Damien Dempsey, Sinead Dolan, Orla Donoghue, Audrey Drohan, Kyran Fitzgerald, Evelyn Flanagan, Andrew Fogarty, Dara Gannon, Lorraine Hanlon, Elizabeth Hassell, Christina Haywood, Karen Hennessy, Isabel Hidalgo, Vincent Hoban, Philip Johnston, Jessica Kavanagh, Bridget Kelly, Sinead Kelly, Ulrike Koch, Dervila Layden, John McCafferty, Áine McConnon, Frank McDermott, Peter McGuire, Gerardine Meaney, Gerald Mills, Ann Mooney, Susan Muldoon, Anne Murphy, Sean Murray, Claire O’Connell, Conor O’Hanlon, Fran O’Rourke, Elaine Quinn, Aileen Ryan, Lisa Shine, Mark Simpson, Charlie Solan, Mary Staunton, Laura Thomas, Ríonach uí Ógáin, Edel Ward, Micéal Whelan, Alexander Wilkinson, Lorraine Woods, Orla Wrynn, Judith Wustemann Produced by: Eilis O’Brien, Claire Percy, Dominic Martella Design: Loman Cusack Design Print: Fine Print Thanks to: Pádraic Conway, Diarmaid Ferriter, Patrick Guiry, Ann Lavan, Damien McLoughlin, Diane Sonnenwald, Regina Uí Chollatáin, William Watson In the compilation of this publication, every care has been taken to ensure accuracy. Any errors or omissions should be brought to the attention of UCD University Relations ([email protected]). -

Annual Report 2008 PRESIDENT Professor Denis I

Institute of Public Administration Annual Report 2008 PRESIDENT Professor Denis I. F. Lucey Head of College, College of Business and Law University College Cork VICE-PRESIDENTS Michael Scanlon John Fitzgerald (retired June 2008) Dermot McCarthy Brian McDonnell Eddie Sullivan (retired June 2008) Tom O’Connor John Tierney Ciaran Connolly Padraig McManus (retired June 2008) Geraldine Tallon Brendan Drumm Philip Furlong BOARD MEMBERSHIP Philip Furlong Des Mahon (Chair until resignation in June 2008) (term of office expired in June 2008) Rody Molloy John A. Murray (appointed Chair in June 2008) (term of office expired in June 2008) Bernard Carey Orla O’Donnell (term of office expired in June 2008) (term of office expired in June 2008) John Tierney Aisling Reynolds-Feighan (appointed Vice-Chair in June 2008) (term of office expired in June 2008) Ciaran Connolly Dermot Ryan (resigned in April 2008) (resigned in February 2008) John Cullen APPOINTED IN JULY 2008 Sean Dorgan Marie Brady (term of office expired in June 2008) Martin Cronin Des Dowling Michael Errity Tom Geraghty Robert Galavan (term of office expired in June 2008) Carmel Keane Cathal Goan Morgan McKnight Philip Hamell Peter Nolan (resigned in February 2008) Julie O’Neill Annette Kennedy (term of office expired in June 2008) Eamon O’Shea Martin McDonald Frances Spillane David Thomas BOARD SUB-COMMITTEES FINANCE AND STRATEGY Julie O’Neill John Tierney (Chair) Eamon O’Shea Marie Brady Frances Spillane Martin Cronin Des Dowling AUDIT COMMITTEE Michael Errity Cathal Goan (Chair) Peter -

Annual Report & Group Financial Statements 2018 Vision, Mission and Values Some Highlights from 2018 Who We Are Statistical Information

A Year in Review Annual Report & Group Financial Statements 2018 Vision, Mission and Values Some Highlights from 2018 Who We Are Statistical Information RTÉ: The Year in Numbers Chair’s Statement What We Made in 2018 Director-General’s Review What We Won in 2018 Financial Review What We Did in 2018 Distribution, Digital, Delivery RTÉ is Ireland’s Raidió Teilifís Éireann Board Today, The 58th Annual Report and Group Financial national public-service Statements for the 12 months ended 31 tomorrow, media organisation December 2018 presented to the Minister for Communications, Climate Action and – on television, radio, Environment in line with sections 109 and 110 together online and mobile. of the Broadcasting Act 2009. Is féidir leagan Gaeilge den Tuarascáil a íoslódáil ó www.rte.ie/annualreport Board of RTÉ Independent Auditor’s Report Other Reporting Requirements Executive Financial Statements Other Statistical Information Corporate Governance Notes Forming Part of the Group Financial History Financial Statements Board Members’ Report Appendix to the Group Financial Statements – Accounting Policies Statement of Board Members’ Responsibilities Vision Mission To champion Irish culture by captivating To enrich Irish life with content that audiences with trusted, engaging and challenges, educates and entertains. challenging content; celebrating our country’s rich diversity; and cultivating Ireland’s talent. Values As an organisation and individually, RTÉ will be outward looking, creative, respectful, sustainable and accountable, collaborative and transparent, and will demonstrate the following behaviours: Outward Looking Have a deep understanding of its audience and their needs. Invest time and energy in monitoring changes in the media landscape. Creative Be resourceful and innovative in how it makes its content. -

Investigative Journalism on the Digital Frontier

16th CLERAUN MEDIA CONFERENCE Friday 11th, Saturday 12th, Sunday 13th November 2016 CLERAUN MEDIA CONFERENCES MEDIA REPORTS Chartered Accountants House, 47-49 Pearse Street, Dublin 2 Scheduled to take place every two years, the professional issues which arise in the course of Cleraun Media Conferences began in 1986 their work in a positive and constructive way. The and have gradually grown in stature. They now Cleraun Media Forum, with its evening seminars constitute an important forum where media between conferences, has helped to make this an practitioners can address and discuss ethical and on-going process. Investigative Journalism on the Digital Frontier REGISTRATION Earlier conferences led to the publication of the following books: To attend the conference, prior registration is required. Only those who have registered and paid in advance can be guaranteed a place. Conference fees (lunch, available in Chartered Accountants House or nearby, not included): Student: €25 Other: €60 Speakers from Ireland at the Cleraun media events have included (in alphabetical order): Register at: www.cleraunmedia.com David Adams, Tony Allwright, Rolande Anderson, Peter Johnston, Peter Kelly, Mary Kenny, John Kerry New sources, new tools, Kevin Bakhurst, Michael Beattie, David Begg, Trevor Keane, Colm Keena, Damien Kiberd, Lauren Kierans, On venue and parking see: Birney, Conor Brady, Mark Brennock, John Burke, Stephen Kinsella, Ian Kirk-Smith, Tom Kitt, Pat Leahy, https://goo.gl/5PxZ2k new technologies, new audiences Elaine Byrne, Jack Byrne, Anne