THE WRITING of INDIAN HISTORY, a Review Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crow and Cheyenne Women| Some Differences in Their Roles As Related to Tribal History

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1969 Crow and Cheyenne women| Some differences in their roles as related to tribal history Carole Ann Clark The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Clark, Carole Ann, "Crow and Cheyenne women| Some differences in their roles as related to tribal history" (1969). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1946. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1946 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUB SISTS. ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR. IVIANSFIELD LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE : U-- - ~ CROW AND CHEYENNE WOMEN r SOME DIFFERENCES IN THEIR ROLES AS RELATED TO TRIBAL HISTORY by Carole Ann Clark B.A., University of Montana, 1?66 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1969 Approved by Chairman, Board of iicaminers L, 'Graduate 'School UMI Number: EP35023 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Native American Culture in North Dakota

NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURE IN NORTH DAKOTA Tribal nations are an essential part of North Dakota’s history. All are welcome to explore the reservations and experience Native American culture by learning about each tribe’s history, language and traditions while visiting attractions like reconstructed earthlodge villages. Attend a powwow and celebrate the culture through song Knife River Indian Double Ditch Indian Village and dance. There are approximately 30,000 Native Americans living in North Villages National Dakota. Though the individual tribes Historic Site: have distinct and different origins, Tribes from across histories and languages, Plains Indians the Northern Plains are united by core beliefs and values journeyed to these that emanate from respect for the earth permanent villages and an understanding of humankind’s relationship with nature. to trade, socialize and make war for Chippewa Downs The tribes with the most influence on more than 11,000 today’s North Dakota are the Mandan, years. Hidatsa and Arikara; the Yanktonai, Sisseton, Wahpeton, Hunkpapa and other Dakota/Lakota/Nakota (commonly known as the Sioux) tribes; and the Chippewa and Metis. Visitors are welcome to explore the reservations and discover the beauty of Native American culture. Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site: Standing Rock Monument This was the principal fur trading post of the American Fur Company and between 1828 and 1867, the most important fur trade post on the Upper Missouri River. MHA Nation Interpretive Center Day 1 Morning — Fort Yates The Standing Rock: Held sacred, the story tells of a woman and her child turned into stone. Sitting Bull Burial Site: The original gravesite of the Hunkpapa Lakota leader. -

Lewis and Clark Adventure Tour

Create Your Own Corps of Discovery Follow in the Footsteps of Lewis and Clark Legends are often described as “an extremely famous or notorious person, especially in a particular field.” Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery are true legends. Sent off to claim uncharted territories and collect specimens and make friends with whomever they meet, the explorers hit the jackpot in North Dakota! The real adventure for Meriwether Lewis and William Clark began here, in what is now North Dakota. The explorers spent more consecutive days in North Dakota than any other state on the expedition, wintering near present-day Washburn at Fort Mandan. Two centuries later, you can see the same landscape at 28 locations recognized by the State Historical Society as significant to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. To experience this adventure for yourself, contact North Dakota Tourism at 1-800-435-5663 or visit www.ndtourism.com. Ask for a copy of Tourism’s Lewis & Clark Trail Guide, which highlights attractions and activities found along the trail in North Dakota. SITES TO SEE On-A-Slant Indian Village/Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park On-A-Slant Indian Village was occupied by Mandan Indians between 1650 and 1750. About 1,000 people lived in the village, but by the time of Lewis and Clark, most had been wiped out by smallpox. Today, reconstructed earthlodges overlook the Heart and Missouri rivers, giving a sense of scale and lifestyle. Each lodge is 30 to 40 feet in diameter and stands 10 to 12 feet high. A small museum offers a wonderful interpretive exhibit. -

Iowa City, IA 52242-1322 Anthropology University of Wyoming Phone: (319) 335-1425 Dept

73nd Annual Plains Anthropological Conference CONFERENCE PROGRAM & ABSTRACTS Iowa City, Iowa October 14-17, 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Conference Host: University of Iowa Conference Committee: • Matthew E. Hill Jr. (co-chair) • Matthew G. Hill (co-chair) • Margaret Beck (program & abstract coordinator) • John Hedden (tour leader) • Cindy Nagel (tour leader) • Marlin Ingalls (tour leader) • William Whittaker (tour leader) We thank the staffs of the UI Center for Conferences and the Sheraton Iowa City Hotel for their exceptional support services for this conference. In particular, we thank Heather Kruse and Katie Johnson for all their patience and help. Several individuals made special contributions to the success of this conference, including Amy Bleier, Dale Henning, Shari Knight, Kelly Flinn, Chris Johnston, Marty Mehlert, and Beverly Poduska. We also wish to thank the many volunteers and generous sponsors of the 73nd Plains Anthropological Conference. About the 2015 Plains Anthropological Conference Logo: The logo is an adaptation of a bison incised into a large catlinite tablet. The tablet was recovered from the Blood Run/Rock Island National Historic Landmark site (13LO2/39LN2) located on both sides of the Big Sioux River near Sioux Falls, SD. The immense site, with both late prehistoric and protohistoric Oneota tradition villages and mound groups, is generally identified with the ancestral Omaha/Ponca with much evidence of ancestral Ioway/Oto residence as well. Incised tablets from Blood Run bear motifs including bison, small mammals, birds, bird men, arrows, and various stylized elements, sometimes superimposed on both sides of the same tablet. Ethnographic accounts suggest that these tablets may have functioned in hunting magic. -

White Shield) Newsletter July, 2014 Volume 2 Issue 21

NAhtAsuutaaka’ (White Shield) Newsletter July, 2014 Volume 2 Issue 21 Dorreen Yellow Bird, Editor [email protected]/701-421-2876 Chris Robinson and Malnourie win Ree Cross Fit competition Chris Robinson and Thom Malnouri push through competiton to take win. The White Shield Ree Fitness Center hosted the cross fit competition June 11th where more than 20 athletes competed, said Brad Kroupa, trainer/cross fit coach. Some of those athletes came from as far way as Canada and Wisconsin. There were five reservations represented: Ft. Mojave, AZ; Wind River, Wyo; Seminole reser- (Continued on page 4) 1 From the desk of Fred Fox,Vice Chairman & Councilman for White Shield Greeting Elders and Community Members, Summer is finally here and the 4th of July celebration is this week. I know the Community Board and the White Shield Segment office is having a big celebration with lots of games, prizes and food. Of course, there will be a firework show to end the night. Hopefully everyone can make it out and enjoy the day at the complex. White Shield powwow is around the corner and the powwow committee is making its final preparations before the first grand entry and passing out its morning rations to all of the visitors and campers. I would like to thank this year’s committee for all their hard work all year. They have set some high standards with all their fundraising activities. Next year the Arikara Celebration will have a new $1 million dance arbor, so there will be a big push to get it done early next summer. -

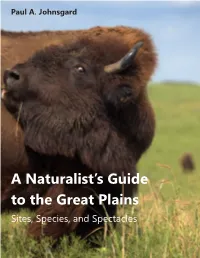

A Naturalist's Guide to the Great Plains

Paul A. Johnsgard A Naturalist’s Guide to the Great Plains Sites, Species, and Spectacles This book documents nearly 500 US and Canadian locations where wildlife refuges, na- ture preserves, and similar properties protect natural sites that lie within the North Amer- ican Great Plains, from Canada’s Prairie Provinces to the Texas-Mexico border. Information on site location, size, biological diversity, and the presence of especially rare or interest- ing flora and fauna are mentioned, as well as driving directions, mailing addresses, and phone numbers or internet addresses, as available. US federal sites include 11 national grasslands, 13 national parks, 16 national monuments, and more than 70 national wild- life refuges. State properties include nearly 100 state parks and wildlife management ar- eas. Also included are about 60 national and provincial parks, national wildlife areas, and migratory bird sanctuaries in Canada’s Prairie Provinces. Numerous public-access prop- erties owned by counties, towns, and private organizations, such as the Nature Conser- vancy, National Audubon Society, and other conservation and preservation groups, are also described. Introductory essays describe the geological and recent histories of each of the five mul- tistate and multiprovince regions recognized, along with some of the author’s personal memories of them. The 92,000-word text is supplemented with 7 maps and 31 drawings by the author and more than 700 references. Cover photo by Paul Johnsgard. Back cover drawing courtesy of David Routon. Zea Books ISBN: 978-1-60962-126-1 Lincoln, Nebraska doi: 10.13014/K2CF9N8T A Naturalist’s Guide to the Great Plains Sites, Species, and Spectacles Paul A. -

Lake Sakakawea and the West River Area

SHOPPING & SERVICE! FARMERS UNION OIL COMPANY Is your gateway 1-Stop for visitors to Lake Sakakawea and the West River area In addition to gas, diesel, propane and a vehicle service department, Plus a food bar with: there is much more. Convenience Store Featuring: • Snacks • 24-7 Card Pumps • Clothing & Hardware • North Dakota Lottery Tickets • Tourist Information • Tires, batteries and service technicians on duty 1600 Hwy 49 N, Beulah • 873-4363 2 101 THINGS TO DO | 2018 Contents Communities 5 Beulah 3939 Parshall 1414 Center 4444 Pick City 1616 Dunn County 4747 Stanton 1717 Garrison 4949 Stanley 2020 Max 5050 Turtle Lake 2121 Makoti 5353 Underwood 2121 Coleharbor 5656 Washburn 2121 White Shield 5858 Wilton 2525 Hazen 6161 Watford City 3131 McClusky 6262 Williston 3333 New Town 101 THINGS TO DO | 2018 3 Patient Centered Medical Neighborhood Here At Home CARING FOR OUR COMMUNITY: VISITING SPECIALISTS: • Primary Care Services for all ages • Podiatry • Lab & Complete Radiology Services • Orthopedics • Physical, Occupational, Speech Therapy • Obstetrics & Gynecology (OB/GYN) • Respiratory Therapy • Psychiatry • Behavioral Health • Cardiology • Licensed Dietician Education • General Surgery • General Surgery • Employee Assistance Programs • Hospice Care • Worksite Wellness Education and Health Screenings • Care Coordination for Seniors • Emergency Care • Sliding Fee Scale & Charity Care Sakakawea • Visiting Nurse Services Medical Center 1312 Hwy 49 North, Beulah 510 8th Ave NE, Hazen 748-2225 Please Call For 873-4445 111 E Main Street, Center 794-8798 More Information 510 8th Ave NE, Hazen 748-2256 220 4th Ave SW, Killdeer 764-5822 4 101 THINGS TO DO | 2018 Beulah Area Camping - Spring to Fall Mercer County Fair 1 The south side of Lake Sakakawea has plenty 3 July 12-15 of camping options open for the outdoors- Come on back to Beulah this July when the oriented adventurers out there. -

North Dakota Travelers

Passport to NNorthorth DDakotaakota History All in a day’s JJourneyourney A traveler’s guide Revised Edition–2009 Useful Websites Passport to for North Dakota Travelers Passport to ND Historic Sites www.nd.gov/hist State Historical Society of North Dakota–www.nd.gov/hist History Published by Tourism Guide, ND Map, Cultural Heritage Guide, The Partners in the Passport to History Program: Hunting and Fishing Guide–www.ndtourism.com These pocket sized guides are being distributed under a grant from Tesoro Corporation. This project was initiated by a grant from USDA Forest Service for the development County and Local Museums–www.nd.gov/hist of the passport concept. Major working partners include: State Historical Society of North Dakota and its North Dakota Books, Publications Foundation; North Dakota Department of Commerce- www.nd.gov/hist/museumstore Tourism Division; Bismarck-Mandan Convention & Visitors Bureau; North Dakota Parks and Recreation Department; North Dakota Geological Survey; Kadrmas, Lee & Jackson, USDA Forest Service–www.fs.fed.us/r1/dakotaprairie Inc., Bismarck; The Bismarck Tribune; The Museum Store–North Dakota Heritage Center, Bismarck; Cass Clay State Historical Society of North Dakota Foundation Creamery, Inc., Fargo; Dan’s SuperMarkets of Bismarck, www.statehistoricalfoundation.com Mandan and Dickinson; Leevers Foods, Devils Lake and Regional Stores; Hornbacher’s Foods, Fargo-Moorhead; For Free admission to STATE HISTORIC SITES Miracle Marts, Minot; Economart, Williston; ND Grocers Join the Foundation at www.statehistoricalfoundation.com Association; and many state and federal historic sites across North Dakota. PO Box 1976 Bismarck, ND 58502 701-222-1966 Located in the North Dakota Heritage Center State Capitol Grounds Northern Great Plains Locations Flasher Michigan Mohall Cavalier • • 81 Fitterer Gas 3845 Highway 21 Michigan Tesoro, LLC Highway 2 and Front Street Rolette St. -

Nahtasuutaaka' (White Shield) News Journal

NAhtAsuutaaka’ (White Shield) News Journal June 2018 Volume 4 Issue 60 Dorreen Yellow Bird, [email protected]/701-421-2876 Architect Drawing of White Shield’s New Administration Building New Buildings in White Shield Add to Growth The community of White Shield is growing as fast as wildflowers on the green, rolling prairie. One of the more stately and beautiful is the new White Shield Administration building (photo above). It looks as if it stepped off the architect’s easel. It will fit nicely next to the Culture Center, Headstart building, and new School. The new school will hear the sounds of children this fall. The school is scheduled to open in August if everything falls into place as the contractors’ hope. (continued on page 3) 1 From the desk of Fred Fox, Councilman, East Segment, White Shield, ND 58540 Hello Community members and Elders. The community had a tough month with many deaths of our loved ones and most notably our long-time Chief of the Arikara people, Bobby Bear. I want to send my condolences to the families. I know no words can explain the loss of a loved one. Summer is finally here, and few of the powwows around the reservation are already finished, with Four Bears, Twin Buttes, and Parshall turning out to be huge successes. Lots of relatives travel near and far, and we know the White Shield “Arikara Celebration” is going to be the biggest and best Celebration White Shield has ever had. We will have the Celebration, along with an Indian Nationals Finals Rodeo Tour, “White Shield Stampede,” Horse Races, Softball Tournament, and a first-time-ever Golf Tournament in Garrison. -

Territory and Sovereignty on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, 1934-1960

TAKEN LANDS: TERRITORY AND SOVEREIGNTY ON THE FORT BERTHOLD INDIAN RESERVATION, 1934-1960 by Angela K. Parker A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Philip J. Deloria, Chair Professor Gregory E. Dowd Associate Professor Stuart A. Kirsch Associate Professor Tiya A. Miles ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to my advisor, Phil Deloria, and my dissertation committee: Greg Dowd, Tiya Miles, and Stuart Kirsch. Through their examples I have begun to learn what it means to be a rigorous, creative, and kind scholar. Phil and Greg threw the weight of their institutional support behind me at every milestone of my program, and offered their personal support during the most difficult times of the past seven years. My favorite experience in graduate school was completing my prelims field with Phil, because it meant that I got to talk history with him for an hour every week. I will probably never achieve the easy brilliance that made most of the people in my Art History seminar say after he guest lectured, ―That‟s your advisor? You‘re so lucky!‖ But it has been exciting to benefit from and be pushed by a powerful mind at the top of his game. Greg has taught me to be a kinder, more insightful scholar. He is all that is best about history as a discipline: thoughtful, rigorous, creative in his analysis, and finely attuned to the human story. Even better, he carries his powerful intellect and insight with great modesty and humility; it was not until I completed prelims that I understood how deeply his works are respected by all who study early America. -

"The Hidatsa Or Gros Ventres" by Edward S. Curtis

From the World Wisdom online library: www.worldwisdom.com/public/library/default.aspx THE HIDATSA TRADITION, HABITAT, AND CUSTOMS THE Hidatsa, commonly known under the inappropriate appellation “Gros Ventres of the Missouri,” differed from most of the tribes of the northern plains in that they were a sedentary and semi-agricultural people, gaining part of their livelihood, of course, by the chase. Their habitat for many generations has been along the Missouri from Heart river to the Little Missouri, in North Dakota. Fortunately the traditions of the Hidatsa are suffi ciently clear to give a comprehensive idea of their movements since reaching their present home-land, and of the time previous important glimpses may be had from their legendary lore. According to these legends, for a long time after their mythical emergence from the under-world they called themselves Mídhokats.1 From time to time the Mídhokats moved toward the land of snows, away from their primal land where summer was perpetual and the birds were ever singing. They were so undeveloped a people that very little account of their wandering was preserved in the stories of the old men. They lived nearly naked, and raised corn, tobacco, squashes, beans, and sunfl owers. Their efforts were directed solely toward preservation of life, and they had no songs nor ceremonies. As they drifted northward a tribe of people resembling them in appearance and speaking a language like their own was met near a lake. The wanderers inquired of the lake people: “Whence came you?” They answered, “We came from under the earth, far down in the country where corn, tobacco, and other things grow in great plenty.” “These must be our brothers,” said the Mídhokats, “as they speak our language and came from below as did we.” Together they moved about in search of game, going ever southwestward. -

Equitable Compensation Act Hearing

S. HRG. 107–268 EQUITABLE COMPENSATION ACT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON FEDERAL OBLIGATION TO EQUITABLE COMPENSATION TO THE FORT BERTHOLD AND STANDING ROCK RESERVATIONS AUGUST 30, 2001 NEW TOWN, ND ( EQUITABLE COMPENSATION ACT S. HRG. 107–268 EQUITABLE COMPENSATION ACT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON FEDERAL OBLIGATION TO EQUITABLE COMPENSATION TO THE FORT BERTHOLD AND STANDING ROCK RESERVATIONS AUGUST 30, 2001 NEW TOWN, ND ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 77–528 PDF WASHINGTON : 2001 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii, Chairman BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado, Vice Chairman FRANK MURKOWSKI, Alaska KENT CONRAD, North Dakota JOHN McCAIN, Arizona, HARRY REID, Nevada PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming PAUL WELLSTONE, Minnesota ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota JAMES M. INHOFE, Oklahoma TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota MARIA CANTWELL, Washington PATRICIA M. ZELL, Majority Staff Director/Chief Counsel PAUL MOOREHEAD, Minority Staff Director/Chief Counsel (II) C O N T E N T S Page Statements: Baker, Biron ...................................................................................................... 30 Baker, Frederick, enrolled member, Three Affiliated Tribes ........................ 26 Burr, Joyce, educational consultant, Three Affiliated Tribes ....................... 32 Conrad, Hon. Kent, U.S. Senator from North Dakota .................................. 2 Danks, John H. member, Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara Elder Organization .