The Yamanote Line on Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unifying Rail Transportation and Disaster Resilience in Tokyo

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Architecture Undergraduate Honors Theses Architecture 5-2020 The Yamanote Loop: Unifying Rail Transportation and Disaster Resilience in Tokyo Mackenzie Wade Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/archuht Part of the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Citation Wade, M. (2020). The Yamanote Loop: Unifying Rail Transportation and Disaster Resilience in Tokyo. Architecture Undergraduate Honors Theses Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/archuht/41 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Yamanote Loop: Unifying Rail Transportation and Disaster Resilience in Tokyo by Mackenzie T. Wade A capstone submitted to the University of Arkansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Honors Program of the Department of Architecture in the Fay Jones School of Architecture + Design Department of Architecture Fay Jones School of Architecture + Design University of Arkansas May 2020 Capstone Committee: Dr. Noah Billig, Department of Landscape Architecture Dr. Kim Sexton, Department of Architecture Jim Coffman, Department of Landscape Architecture © 2020 by Mackenzie Wade All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge my honors committee, Dr. Noah Billig, Dr. Kim Sexton, and Professor Jim Coffman for both their interest and incredible guidance throughout this project. This capstone is dedicated to my family, Grammy, Mom, Dad, Kathy, Alyx, and Sam, for their unwavering love and support, and to my beloved grandfather, who is dearly missed. -

Thinking from the Yamanote: Space, Place and Mobility in Tokyo's Past and Present

This is a repository copy of Thinking from the Yamanote: space, place and mobility in Tokyo's past and present . White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/117685/ Version: Published Version Article: Pendleton, M. orcid.org/0000-0002-4266-2470 and Coates, J. (2018) Thinking from the Yamanote: space, place and mobility in Tokyo's past and present. Japan Forum, 30 (2). pp. 149-162. ISSN 0955-5803 https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2017.1353532 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Japan Forum ISSN: 0955-5803 (Print) 1469-932X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjfo20 Thinking from the Yamanote: space, place and mobility in Tokyo's past and present Mark Pendleton & Jamie Coates To cite this article: Mark Pendleton & Jamie Coates (2018) Thinking from the Yamanote: space, place and mobility in Tokyo's past and present, Japan Forum, 30:2, 149-162, DOI: 10.1080/09555803.2017.1353532 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2017.1353532 © 2018 The Author(s). -

Tokyo Metoropolitan Area Railway and Subway Route

NikkNikkō Line NikkNikkō Kuroiso Iwaki Tōbu-nikbu-nikkkō Niigata Area Shimo-imaichi ★ ★ Tōbu-utsunomiya Shin-fujiwara Shibata Shin-tochigi Utsunomiya Line Nasushiobara Mito Uetsu Line Network Map Hōshakuji Utsunomiya Line SAITAMA Tōhoku Shinkansen Utsunomiya Tomobe Ban-etsu- Hakushin Line Hakushin Line Niitsu WestW Line ■Areas where Suica・PASMO can be used RAILWAY Tochigi Oyama Shimodate Mito Line Niigata est Line Shinkansen Moriya Tsukuba Jōmō- Jōetsu Minakami Jōetsu Akagi Kuzū Kōgen ★ Shibukawa Line Shim-Maebashi Ryōmō Line Isesaki Sano Ryōmō Line Hokuriku Kurihashi Minami- ban Line Takasaki Kuragano Nagareyama Gosen Shinkansen(via Nagano) Takasaki Line Minami- Musashino Line NagareyamaNagareyama-- ō KukiKuki J Ōta Tōbu- TOBU Koshigaya ōōtakanomoritakanomori Line Echigo Jōetsu ShinkansenShinkansen Shin-etsu Line Line Annakaharuna Shin-etsu Line Nishi-koizumi Tatebayashi dōbutsu-kōen Kasukabe Shin-etsu Line Yokokawa Kumagaya Higashi-kHigashi-koizumioizumi Tsubamesanjō Higashi- Ogawamachi Sakado Shin- Daishimae Nishiarai Sanuki SanjSanjōō Urawa-Misono koshigaya Kashiwa Abiko Yahiko Minumadai- Line Uchijuku Ōmiya Akabane- Nippori-toneri Liner Ryūgasaki Nagaoka Kawagoeshi Hon-Kawagoe Higashi- iwabuchi Kumanomae shinsuikoen Toride Yorii Ogose Kawaguchi Machiya Kita-ayase TSUKUBA Yahiko Yoshida HachikHachikō Line Kawagoe Line Kawagoe ★ ★ NEW SHUTTLE Komagawa Keihin-Tōhoku Line Ōji Minami-Senju EXPRESS Shim- Shinkansen Ayase Kanamachi Matsudo ★ Seibu- Minami- Sendai Area Higashi-HanHigashi-Hannnō Nishi- Musashino Line Musashi-Urawa Akabane -

Construction of Ueno–Tokyo Line

Special Feature Construction of Ueno–Tokyo Line JR East Construction Department Introduction to support through services between the Utsunomiya, Takasaki, Joban, and Tokaido lines (Fig. 1). The Council East Japan Railway Company (JR East) has a wide-ranging for Transport Policy Report No. 18 published in January operations area from Kanto and Koshin’etsu to Tohoku. When 2000, targeted opening of the Ueno–Tokyo Line (A1) by JR East was established in 1987, traffic conditions on most 2015. In November 2007, the Minister of Transport gave sections of conventional (narrow-gauge) lines in the Tokyo permission to change the basic plan to a plan for laying area, including major sections of lines radiating from central new tracks between Tokyo Station and Ueno Station and Tokyo (Tokaido, Chuo, Joban, Sobu lines), the Yamanote then permission was given in March 2008 to change the Line, etc., had morning rush-hour congestion rates in excess railway facilities. Construction started in May 2008 and was of 200%. As a result, enhancing transportation capacity completed in about 6 years. The line opened on 14 March to alleviate congestion was a major issue. Furthermore, 2015, following 5–month training run. with subsequent diversification of values accompanying social changes, users’ railway needs went beyond merely Expected Effects alleviating congestion to shorter travel times and improved comfort while travelling, etc., so problems related to Alleviating congestion on Yamanote and Keihin-Tohoku improving transportation in the Tokyo area also diversified. In lines this context, JR East has taken various initiatives to improve The sections between Ueno Station and Okachimachi the quality of railway services. -

From Akihabara 1

Map of YOKOSUKA Area Map of YOKOSUKA Area Chinatown Garden of SANKEIEN Great image of Buddha Battleship of MIKASA Map of Natsushima Area Map of Natsushima Area Zero fighter Natsushima NISSAN shell midden Transportation from Narita Airport to YOKOHAMA Narita Express(N’EX) Narita Airport-YOKOHAMA Approx.90min ¥4,180YEN OFFICIAL HOTEL Yokohama Bay Sheraton Hotel & Towers (Special rates will be provided for the INMARTECH 2002) JAMSTEC YOKOSUKA Headquarters: JAMSTEC YOKOSUKA Headquarters: JAMSTEC YOKOHAMA JAMSTEC YOKOHAMA Presentation Room 1 Lecture Room For General session and Parallel session *Capacity – 108persons *Equipment 120 inch Screen Video Projector DVD Player VHS & S-VHS VideoPlayer Presentation Room 2 Seminar Room For Parallel session and Poster session *Capacity – 60 persons *Equipment 120 inch Screen Video Projector DVD Player VHS & S-VHS VideoPlayer Kaikyu-An for Tea Ceremony at JAMSTEC Kaikyu-An:Hermitage of Ocean sphere Technical Tour National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation Technical Tour National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation How to get to Yokohama Station and area guide from Odaiba (National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation) 1. Take a train "YURIKAMOME Line" for Shinbashi at Funeno kagakukan station near National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation. 2. The fare is 370yen and it takes about 16min.to Shinbashi station. 3. YURIKAMOME LINE Time schedule - every 5min. Route - Shinbashi -- Takeshiba -- Hinode -- shibaura futo -- Odaiba kaihin koen -- Daiba -- Funeno kagakukan -- terekomu senta -- Aomi -- Kokusai tenjijo seimon -- Ariake 4. Change the train at Shinbashi station to Keihin- Tohoku Line-Negishi Line, JR EAST Lines. 5. Take a train for ISOGO or OFUNA (not for Yokohama) 6. -

Suica‐Smart Card Payment System ・ ③ Smart Station Lab

World Usability Day 2012 ICT-based service in public transportation Nov./8/2012 Takeshi NAKAGAWA Frontier Service Development Lab. East Japan Railway Company Agenda ・ ① JR East & FS Lab. Overview ・ ②Suica‐Smart Card Payment System ・ ③ Smart Station Lab. & The latest R&D activities ・ Yamanote-line Trainnet ・ Tokyo Station JR x AR ・ Kamishirube ① East Japan Railway Company & FS Lab. JR East Overview Privatized on April 1st, in 1987 Japan National Railway was divided 6 passenger railway companies JR Hokkaido 1 freight railway company JR East is… JR East Employees 52,076 Group Revenues 2011 $30 billion Stations 1,689 ( Shinkansen 35 ) Railway Lines 70 ( Shinkansen 3 ) JR West Passengers Served Daily 16 million Population of Operating Area 59 million( 125million in Japan ) JR Central JR Shikoku JR Kyushu Transportation ‐ Commuter Train- 5 Transportation -Shinkansen- HAYABUSA was debut! In March, 2011 Max speed is 320km/h = 200 mile/h Harnessing state-of-the art technology and an aim to achieve 320km/h, the fastest operational speed in Japan Lifestyle Business Ad business 7 IT-Suica Business Suica(Smart Card) Business Credit Card Size WiMAX + Wi-Fi Service 8 LCD Display New, Weather, Flight, Ad WIMAX Antenna LCD Display WiMAX-WiFi CMS server R&D Center of JR East Group R&D Center was established on Dec./1st/2001 Aiming toward the construction of a new railway system Frontier Service Development Lab. Advanced Railway System Development Center Safety Research Lab. Disaster Prevention Research Lab. Technical Center Environmental Engineering Research Lab. 2012/12/17 Copyright 2010 Frontier Service Development Lab. All rights reserved. 9 Information Design Group Aiming for easy-to-understand information provision to customers by using Information Communication Technology ② Suica ‐ Smart Card Payment System - Railway in Japan Basic Process on riding train Check a fare Buy Ticket gate onboard gate Fare depends on distance. -

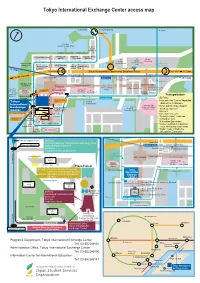

Tokyo International Exchange Center Access Map

Tokyo International Exchange Center access map To Shimbashi To Rainbow Bridge To Toyosu ↑ Daiba Exit Sea Bus (Odaiba Seaside Park) SEAREA ODAIBA SANBANGAI ●Odaiba Marine Park ●Marine House ● ● ● ● ●Hotel Nikko Tokyo Aqua City DECKS SEAREA ODAIBA Odaiba Tokyo Beach GOBANGAI ● ● Ariake Daiba Sta. Ariake Odaiba-kaihinkoen Sta. Ariake Colosseum Tennis-no-mori Shiokaze Park Ariake JCT Sports Center Ariake tennis ● ● ● Park (North Area) ●Fuji Television no mori Sta. GRAND PACIFIC TradePia Daiba Frontier ● 357 To LE DAIBA Odaiba Bldg. Tokyo Wangan doro Osaki Rinkaifukutoshin Exit Shuto Metropolitan Expressway Bayshore Route Ariake Exit To Chiba Tokyo Teleport Sta. Kokusai-tenjijo Sta. da ・i Hane To O West Promenade Rinkai Line ●Tokyo Water To Shin-kiba Science Museum Ariake Sta. ● Shiokaze Park East Promenade (South Area) FUNE-NO Center Promenade KAGAKUKAN Tokyo Yumenoohashi ●Tokyo Bay Ariake STA. ●Tokyo Fashion Town Sea Bus Funenokagakukan Palette Town Bridge Washington Hotel (Museum Museum (Venus Fort, ● -eki-mae Academic ● of of Maritime Sun Walk) Ferris Wheel Ariake Frontier Maritime Science Park Building Transportation ) ● Science Higashi Yashio Aomi 1 chome Aomi Sta. Greenway YURIKAMOME Kokusai tenjijo <By Train> Shinboru-puromunado seimon Sta. ・3 min. walk from "Fune-no Kagakukan" Tokyo -koen-mae Sea Bus International (Palette Town) (East exit) on Yurikamome Tokyo Big Sight ・15 min. walk from "Tokyo Teleport" National Museum of (Tokyo Inter national Exchange ● Sea Bus Emerging Science Exhibition Center) (B exit) on Rinkai Line (Tokyo Big Sight) Center and Innovation <By Car> Nihon-kagaku-miraikan-mae ● ● AIST Tokyo 5 min. from these exits: Tokyo Waterfront ・"Rinkaifukutoshin", eastbound Tokyo-kowan-godo Wangan on Bayshore route, -chosha-mae Police Station ● ● ● Time 24 Metropolitan Expressway Aomi Frontier Building Tokyo ・"Ariake", westbound on Bayshore Kowan Godo Chosha ● Telecom center Sta. -

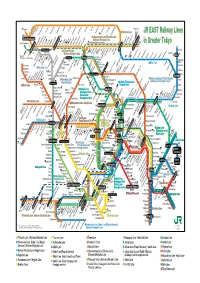

JR EAST Railway Lines in Greater Tokyo

- - Joetsu Line Nikko Line Kiryu Sano - Omata 30 - - oshima Isesaki Iwajuku Tomita Iwafune Tochigi Ryomo Line JR EAST Railway Lines Maebashi Kunisada Ashikaga Maebashi Komagata Yamamae Ohirashita 新前橋 熊谷 - Omoigawa 16 Utsunomiya Line(Tohoku- Line) Shim-Maebashi Shonan-Shinjuku- Line Joetsu- Shinkansen Kita- Tohoku.Yamagata.Akita Shinkansen 小山 KoganeiJichiidaiIshibashiSuzumenomiya宇都宮 in Greater Tokyo KuraganoShimmachiJimboharaHonjoOkabeFukayaKagohara GyodaFukiage KonosuKonosuKitamotoOkegawaKita-AgeoAgeo Miyahara Ino saki Honjowaseda- Kumagaya Utsunomiya Katsuta 17 Takasaki Line Toro Kuki Koga Nogi Oyama Taka 本庄早稲田 Omiya 高崎 - Higashi- Hasuda Shin- Suigun Line 水戸 Shonan-Shinjuku Line 大宮 ShiraokaShiraoka Higashi- Mamada Nagano Kurihashi Mito Shinkansen Shinetsu Line Kawagoe Omiya Saitama Yuki Higashi-Yuki KawashimaTamado ShimodateNiihari Iwase Haguro Fukuhara rii shintoshin Washinomiya Yamato Kitafujioka Yo d oYo 川越 Kairakuen Tansho Yono (Extra) Kodama Takezawa Nishi- 31Mito Line Oku-Tama Matsuhisa Kawagoe Nisshin Kita-Urawa Inada Akatsuka Gummafujioka - Orihara Sashiogi Minami- Urawa Otabayashi Shiromaru 15 Hachiko Line Ogawamachi Matoba Yono Kita-Yono Naka- shigaya Kasama Uchihara Myokaku Minami-Furuya Urawa 南浦和 Hatonosu Kasahata Higashi-Urawa Higashi- KawaguchiMinami-Ko Yoshikawa Musashi-Urawa Minami-Urawa 友部 Kori Ogose Musashi-Takahagi onohommachi Shim-Misato Shishido Y 武蔵浦和 Warabi Tomobe Nishi-Urawa 22 - [ ] Kawai Moro 19 Kawagoe Line Nishi-Kawaguchi Joban Line Local Train -Chiyoda Iwama MitakeSawaiIkusabataFutamataoIshigamimaeHinatawadaMiyanohiraOme -

Full Upgrade of ATOS to Improve Safety and Reliability of Railway Services

Hitachi Review Vol. 63 (2014), No. 8 493 Featured Articles Full Upgrade of ATOS to Improve Safety and Reliability of Railway Services Yasuhiro Yoshida OVERVIEW: Tokyo, Japan’s capital, has become one of the world’s major Kouhei Akutsu cities through the ongoing migration of people from the provinces as the Yasuhiro Yumita country’s economy has grown. The railways serving the Tokyo region are an important part of the social infrastructure that support the functioning of the Ryuji Yamagiwa city over a wide area. Their ongoing development has created a complex and Hideki Osumi high-density network, including the Chuo and Shonan-Shinjuku Lines, among Mitsunori Okada others. Future railway systems are expected to satisfy new requirements Kiyosumi Fukui arising from the changing social environment, including the utilization of existing infrastructure to allow different operators to run services on the same track, and further improvements to passenger services. To achieve this, JR-East and Hitachi aim to provide safe and reliable management of railway traffic, and to help improve services to all stakeholders, including passengers, through initiatives such as the fusion of control and information technologies. has facilitated ongoing work to add new lines to the INTRODUCTION system without affecting those lines where it was WHEN the East Japan Railway Company (JR- already operating. With the system now covering East) was established in 1987, very little progress 20 lines, amounting to a combined length of about had yet been made on the computerization of train 1,270 km, it has become an important part of the social traffic management on its metropolitan lines in infrastructure, essential to the ongoing provision of the Tokyo region, with traffic management for safe and reliable transportation (see Fig. -

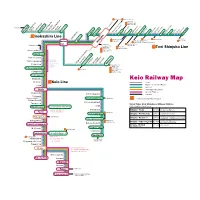

Keio Railway

Oedo Line Marunouchi Line Chuo Line Yurakucho Line Namboku Line Chuo Line Keio New Line Inokashira-koen Mitakadai FujimigaokaTakaidoHamadayamaNishi- Kichijoji eifuku Kugayama Eifukucho Shinjuku-sanchomeAkebonobashi Kudanshita OgawamachiIwamotocho Hamacho KikukawaSumiyoshiNishi-ojima Higashi-ojima Ichinoe Mizue Shinozaki bocho Ojima Ichigaya m Inokashira Line Hatagaya Hatsudai Ji Bakuroyokoyama Morishita Funabori Motoyawata Daitabashi Hanzomon Line Oedo Line Hanzomon Line Sobu Line Tozai Line Sobu Line (Bakurocho) Keisei Line Meidai Sasazuka Shinjuku Asakusa Line (Higashi-nihombashi) mae Chuo Line Marunouchi Line Setagaya Line Yamanote Line Chiyoda Line Saikyo Line Mita Line Toei Shinjuku Line Odakyu Line Hanzomon Line Shimo-takaido Marunouchi Line Keio Line Oedo Line Sakurajosui Kami-kitazawa Commuter Hachimanyama Rapid Train does not stop Higashi-matsubaraShindaita Ikenoue Komaba- Shinsen todaimae Shibuya Roka-koen at these Shimo-kitazawa Yamanote Line stations Saikyo Line Chitose-karasuyama Toyoko Line Odakyu Line Den-en-toshi Line Ginza Line Sengawa Hanzomon Line Tsutsujigaoka Shibasaki Keio Railway Map Kokuryo Keio Line Local Fuda Rapid / Commuter Rapid Express Chofu Semi-Special Express Special Express Nishi-chofu Keio-tamagawa Transfer Tobitakyu Ajinomoto Stadium Keio-inadazutsumi Nambu Line Lines accepting Passnet Card Musashinodai Keio-yomiuri-land Tama-reien Travel Times from Shinjuku or Shibuya Stations Higashi-fuchu Fuchukeiba-seimonmae Inagi (fastest daytime travel times) Express (Inbound) runs Wakabadai Shinjuku - Fuchu 19 -

Tokyo Periphery and Rail Transit Investment Opportunities May Emerge Beyond Central Tokyo

Japan - May 2020 Tokyo Periphery and SPOTLIGHT Savills Research Rail Transit ©ESR LTD Tokyo Periphery and Rail Transit Investment opportunities may emerge beyond central Tokyo THE WORLD’S MOST RELIABLE RAIL global comparisons, Tokyo is often ranked as having the most efficient and punctual Summary NETWORK While real estate value is unsurprisingly railway system, especially considering its vast • Land prices at many station-side concentrated in Tokyo’s central business transport capacity. areas on the Tokyo periphery district, namely the central five wards of These factors are a key driver of real estate have already surpassed 2008 Chiyoda, Chuo, Minato, Shinjuku, and Shibuya, value in Tokyo’s periphery, making outlying levels and, in many cases, have Greater Tokyo’s comprehensive rail system areas appealing for residents, businesses, and seen stronger growth than key grants great accessibility to outlying areas. investors alike. That being said, popularity and hubs in the central five wards. The key advantage of Tokyo’s rail network is perceptions undoubtedly vary by area. Certain its density and globally-renowned punctuality. areas have stood out during the current cycle, • Population growth in Greater Although delays certainly occur and carriages in some cases posting stronger growth than Tokyo has outperformed become overcrowded during rush hour, the top areas in central Tokyo (Map 1). forecasts based on the 2015 commuters can largely count on trains arriving The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting census, with population on time and at a high frequency. Looking at mitigation steps will undoubtedly curb estimates for most wards and cities already exceeding the levels forecasted for October Map 1: Greater Tokyo Railway Lines And Daily Passengers Per Station 2020. -

East Japan Railway Company (JR East) Management Planning Department

20 Years After JNR Privatization Vol. 2 East Japan Railway Company (JR East) Management Planning Department Introduction to cut costs and increase productivity across the board. JR East has worked to reduce long-term debt inherited Immediately after the JNR reforms a little more than 20 from JNR—one of the company’s most important tasks— years ago, there was a sense of crisis in the air at JR East and although total long-term debt increased temporarily over whether the new company would be profitable and at purchase of the Tohoku and Joetsu shinkansen could really recapture the glory days of rail. Nevertheless, infrastructure in 1991, we have repaid about ¥2.7 trillion all JR East employees were determined to show in 20 years. The resultant drop in interest payments has unrelenting resolve and determination from the outset helped stabilize the company’s operations. with the intent of creating a new railway era. Thanks to such efforts, JR East has continually posted Since those first days, we have striven to enhance the favourable operating results and became fully privatized competitiveness of our railway operations despite the following listing on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, three effects of the collapse of the Japanese economic ‘bubble’ sales of government-held shares, and amendment of the in 1991, the Lost Decade period of low growth, and JR Law. It is no exaggeration to say that we have intensifying competition with other transport modes. achieved the objectives of the JNR reforms with Specifically, we have expanded our shinkansen network, independent management of a profitable company and increased carrying capacity in the Tokyo metropolitan have helped restored railways in Japan to their former area, and in recent years, enhanced seamless glory (Figs.