Mr. Justice Douglas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Cheers for Judicial Restraint: Justice White and the Role of the Supreme Court Justice White and the Exercise of Judicial Power

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2003 Two Cheers for Judicial Restraint: Justice White and the Role of the Supreme Court Justice White and the Exercise of Judicial Power Dennis J. Hutchinson Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dennis J. Hutchinson, "Two Cheers for Judicial Restraint: Justice White and the Role of the Supreme Court Justice White and the Exercise of Judicial Power," 74 University of Colorado Law Review 1409 (2003). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWO CHEERS FOR JUDICIAL RESTRAINT: JUSTICE WHITE AND THE ROLE OF THE SUPREME COURT DENNIS J. HUTCHINSON* The death of a Supreme Court Justice prompts an account- ing of his legacy. Although Byron R. White was both widely admired and deeply reviled during his thirty-one-year career on the Supreme Court of the United States, his death almost a year ago inspired a remarkable reconciliation among many of his critics, and many sounded an identical theme: Justice White was a model of judicial restraint-the judge who knew his place in the constitutional scheme of things, a jurist who fa- cilitated, and was reluctant to override, the policy judgments made by democratically accountable branches of government. The editorial page of the Washington Post, a frequent critic during his lifetime, made peace post-mortem and celebrated his vision of judicial restraint.' Stuart Taylor, another frequent critic, celebrated White as the "last true believer in judicial re- straint."2 Judge David M. -

Edward Douglas White: Frame for a Portrait Paul R

Louisiana Law Review Volume 43 | Number 4 Symposium: Maritime Personal Injury March 1983 Edward Douglas White: Frame for a Portrait Paul R. Baier Louisiana State University Law Center Repository Citation Paul R. Baier, Edward Douglas White: Frame for a Portrait, 43 La. L. Rev. (1983) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol43/iss4/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V ( TI DEDICATION OF PORTRAIT EDWARD DOUGLASS WHITE: FRAME FOR A PORTRAIT* Oration at the unveiling of the Rosenthal portrait of E. D. White, before the Louisiana Supreme Court, October 29, 1982. Paul R. Baier** Royal Street fluttered with flags, we are told, when they unveiled the statue of Edward Douglass White, in the heart of old New Orleans, in 1926. Confederate Veterans, still wearing the gray of '61, stood about the scaffolding. Above them rose Mr. Baker's great bronze statue of E. D. White, heroic in size, draped in the national flag. Somewhere in the crowd a band played old Southern airs, soft and sweet in the April sunshine. It was an impressive occasion, reported The Times-Picayune1 notable because so many venerable men and women had gathered to pay tribute to a man whose career brings honor to Louisiana and to the nation. Fifty years separate us from that occasion, sixty from White's death. -

Supreme Court Database Code Book Brick 2018 02

The Supreme Court Database Codebook Supreme Court Database Code Book brick_2018_02 CONTRIBUTORS Harold Spaeth Michigan State University College of Law Lee Epstein Washington University in Saint Louis Ted Ruger University of Pennsylvania School of Law Sarah C. Benesh University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee Department of Political Science Jeffrey Segal Stony Brook University Department of Political Science Andrew D. Martin University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts Document Crafted On October 17, 2018 @ 11:53 1 of 128 10/17/18, 11:58 AM The Supreme Court Database Codebook Table of Contents INTRODUCTORY 1 Introduction 2 Citing to the SCDB IDENTIFICATION VARIABLES 3 SCDB Case ID 4 SCDB Docket ID 5 SCDB Issues ID 6 SCDB Vote ID 7 U.S. Reporter Citation 8 Supreme Court Citation 9 Lawyers Edition Citation 10 LEXIS Citation 11 Docket Number BACKGROUND VARIABLES 12 Case Name 13 Petitioner 14 Petitioner State 15 Respondent 16 Respondent State 17 Manner in which the Court takes Jurisdiction 18 Administrative Action Preceeding Litigation 19 Administrative Action Preceeding Litigation State 20 Three-Judge District Court 21 Origin of Case 22 Origin of Case State 23 Source of Case 24 Source of Case State 2 of 128 10/17/18, 11:58 AM The Supreme Court Database Codebook 25 Lower Court Disagreement 26 Reason for Granting Cert 27 Lower Court Disposition 28 Lower Court Disposition Direction CHRONOLOGICAL VARIABLES 29 Date of Decision 30 Term of Court 31 Natural Court 32 Chief Justice 33 Date of Oral Argument 34 Date of Reargument SUBSTANTIVE -

Jerome Frank's Impact on American Law

Michigan Law Review Volume 84 Issue 4 Issues 4&5 1986 The Iconoclast as Reformer: Jerome Frank's Impact on American Law Matthew W. Frank University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Judges Commons, and the Legal Biography Commons Recommended Citation Matthew W. Frank, The Iconoclast as Reformer: Jerome Frank's Impact on American Law, 84 MICH. L. REV. 866 (1986). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol84/iss4/29 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 866 Michigan Law Review [Vol. 84:861 THE ICONOCLAST AS REFORMER: JEROME FRANK'S IMPACT ON AMERICAN LA w. By Robert Jerome Glennon. Ithaca: Cornell Uni versity Press. 1985. Pp. 252. $24.95. In the first half of this century, Jerome Frank achieved prominence as a corporate attorney, a legal realist, a New Deal administrator, and finally as a federal appellate court judge. A study of Frank's career does more than testify to the man's extraordinary breadth of interest, energy, and ability; it serves as a pane through which one may witness the enormous changes in law and legal theory from 1930 to 1957. In The Iconoclast as Reformer: Jerome Frank's Impact on American Law, Professor Robert Glennon 1 traces Frank's career and attempts to evaluate Frank's influence in these areas. -

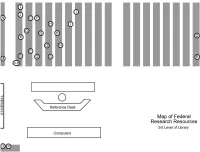

Fedresourcestutorial.Pdf

Guide to Federal Research Resources at Westminster Law Library (WLL) Revised 08/31/2011 A. United States Code – Level 3 KF62 2000.A2: The United States Code (USC) is the official compilation of federal statutes published by the Government Printing Office. It is arranged by subject into fifty chapters, or titles. The USC is republished every six years and includes yearly updates (separately bound supplements). It is the preferred resource for citing statutes in court documents and law review articles. Each statute entry is followed by its legislative history, including when it was enacted and amended. In addition to the tables of contents and chapters at the front of each volume, use the General Indexes and the Tables volumes that follow Title 50 to locate statutes on a particular topic. Relevant libguide: Federal Statutes. • Click and review Publication of Federal Statutes, Finding Statutes, and Updating Statutory Research tabs. B. United States Code Annotated - Level 3 KF62.5 .W45: Like the USC, West’s United States Code Annotated (USCA) is a compilation of federal statutes. It also includes indexes and table volumes at the end of the set to assist navigation. The USCA is updated more frequently than the USC, with smaller, integrated supplement volumes and, most importantly, pocket parts at the back of each book. Always check the pocket part for updates. The USCA is useful for research because the annotations include historical notes and cross-references to cases, regulations, law reviews and other secondary sources. LexisNexis has a similar set of annotated statutes titled “United States Code Service” (USCS), which Westminster Law Library does not own in print. -

The New Investor Tom C.W

The New Investor Tom C.W. Lin EVIEW R ABSTRACT A sea change is happening in finance. Machines appear to be on the rise and humans on LA LAW LA LAW the decline. Human endeavors have become unmanned endeavors. Human thought and UC human deliberation have been replaced by computerized analysis and mathematical models. Technological advances have made finance faster, larger, more global, more interconnected, and less human. Modern finance is becoming an industry in which the main players are no longer entirely human. Instead, the key players are now cyborgs: part machine, part human. Modern finance is transforming into what this Article calls cyborg finance. This Article offers one of the first broad, descriptive, and normative examinations of this sea change and its wide-ranging effects on law, society, and finance. The Article begins by placing the rise of artificial intelligence and computerization in finance within a larger social context. Next, it explores the evolution and birth of a new investor paradigm in law precipitated by that rise. This Article then identifies and addresses regulatory dangers, challenges, and consequences tied to the increasing reliance on artificial intelligence and computers. Specifically, it warns of emerging financial threats in cyberspace, examines new systemic risks linked to speed and connectivity, studies law’s capacity to govern this evolving financial landscape, and explores the growing resource asymmetries in finance. Finally, drawing on themes from the legal discourse about the choice between rules and standards, this Article closes with a defense of humans in an uncertain financial world in which machines continue to rise, and it asserts that smarter humans working with smart machines possess the key to better returns and better futures. -

Jerome Frank's Fact-Skepticism and Our Future*

JEROME FRANK'S FACT-SKEPTICISM AND OUR FUTURE* EDMOND GAHNt I WHEN Dean Rostow asked me to describe the main features of Jerome Frank's legal philosophy, I resolved that-no matter how tentative my sum- mary might be-I must speak in the perspective of the future. For one thing, this is the way he habitually faced and spoke and wrote; it is the way to be faithful to his thought. For another, his philosophy-which he called "fact- skepticism"'-is nothing more or less than a bold confrontation of the future and a flinging of gages at its feet. I believe that Jerome Frank's fact-skepti- cism represents an epoch-making contribution not only to legal theory and procedural reform, but also to the understanding of the entire human condition. The history of our time will record whether we profited by the challenges he bequeathed to us. For about twenty-five years Jerome Frank's coruscating and marvelously restless mind planned and built and developed the meaning of fact-skepticism. Fully aware that his approach was novel, he deliberately repeated and reiter- ated his doctrines, phrased them first this way then that, and summoned analogies from every corner of the cultural world to make his ideas clearer. To justify the repetitions, he used the following story: "Mr. Smith of Denver was introduced to Mr. Jones at a dinner party in Chicago. 'Oh,' said Jones, 'do you know my friend Mr. Schnicklefritz, who lives in Denver?' 'No,' answered Smith. Later in the evening, when Smith referred to Denver, Jones again asked whether Smith was ac- quainted with Schnicklefritz, and again received a negative reply. -

Antitrust and Baseball: Stealing Holmes

Antitrust and Baseball: Stealing Holmes Kevin McDonald 1. introduction this: It happens every spring. The perennial hopefulness of opening day leads to talk of LEVEL ONE: “Justice Holmes baseball, which these days means the business ruled that baseball was a sport, not a of baseball - dollars and contracts. And business.” whether the latest topic is a labor dispute, al- LEVEL TWO: “Justice Holmes held leged “collusion” by owners, or a franchise that personal services, like sports and considering a move to a new city, you eventu- law and medicine, were not ‘trade or ally find yourself explaining to someone - commerce’ within the meaning of the rather sheepishly - that baseball is “exempt” Sherman Act like manufacturing. That from the antitrust laws. view has been overruled by later In response to the incredulous question cases, but the exemption for baseball (“Just how did that happen?”), the customary remains.” explanation is: “Well, the famous Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. decided that baseball was exempt from the antitrust laws in a case called The truly dogged questioner points out Federal Baseball Club ofBaltimore 1.: National that Holmes retired some time ago. How can we League of Professional Baseball Clubs,‘ and have a baseball exemption now, when the an- it’s still the law.” If the questioner persists by nual salary for any pitcher who can win fifteen asking the basis for the Great Dissenter’s edict, games is approaching the Gross National Prod- the most common responses depend on one’s uct of Guam? You might then explain that the level of antitrust expertise, but usually go like issue was not raised again in the courts until JOURNAL 1998, VOL. -

Judicial Supremacy and the Modest Constitution

Judicial Supremacy and the Modest Constitution Frederick Schauert INTRODUCTION Judicial supremacy is under attack. From various points on the politi- cal spectrum, political actors as well as academics have challenged the idea that the courts in general, and the Supreme Court in particular, have a spe- cial and preeminent responsibility in interpreting and enforcing the Constitution. Reminding us that treating Supreme Court interpretations of the Constitution as supreme and authoritative has no grounding in constitu- tional text and not much more in constitutional history, these critics seek to relocate the prime source of interpretive guidance. The courts have an important role to play, these critics acknowledge, but it is a role neither greater than that played by other branches, nor greater than the role to be played by "the people themselves."' The critics' understanding of a more limited function for the judiciary in constitutional interpretation appears to rest, however, primarily on a highly contestable conception of the point of having a written constitution in the first place. According to this conception, a constitution, and espe- cially the Constitution of the United States, is the vehicle by which a de- mocratic polity develops its own fundamental values. A constitution, therefore, becomes both a statement of our most important values and the vehicle through which these values are created and crystallized. Under this conception of the role of a written constitution, it would indeed be a mis- take to believe that the courts should have the preeminent responsibility for interpreting that constitution. For this task of value generation to devolve Copyright © 2004 California Law Review, Inc. -

JUDGE JEROME FRANK Tamm Arnoldt

JUDGE JEROME FRANK Tamm ARNOLDt EW SUCH brilliant, original and many-sided men as Jerome Frank have ever attained judicial eminence in the history of any bench, here or abroad. He was an economist in the sense that he knew and could com- pare all of the different theories by which men of various and conflicting doc- trinaire views strove to create principles which, if followed, would make a na- tion's economy rational, scientific and neat as a trivet or an apple pie. He also knew, perhaps better than any other living judge, the practical problems of finance. As Mr. Justice Douglas recently pointed out,' Jerome Frank "had no superior when it came to an understanding of the ways of high finance and to an analysis of regulatory measures dealing with it." This practical knowledge prevented him from ever being caught in the web of any economic doctrine. He was a lawyer of great technical skill, and he had an extraordinary grasp of the deductive system of wheels within wheels which gives the law its appearance of predictability. He also read widely and with complete skepticism the litera- ture of that brooding omnipresence in the sky known as Jurisprudence or the higher law. He was a student of psychiatry and was able to use that knowledge in his treatment of legal problems. As a writer, he developed a legal philosophy which had tremendous impact on the legal thinking of our time. On the bench, he produced a series of judi- cial opinions outstanding in their uniform fairness, equity and economic soundness. -

“Clean Hands” Doctrine

Announcing the “Clean Hands” Doctrine T. Leigh Anenson, J.D., LL.M, Ph.D.* This Article offers an analysis of the “clean hands” doctrine (unclean hands), a defense that traditionally bars the equitable relief otherwise available in litigation. The doctrine spans every conceivable controversy and effectively eliminates rights. A number of state and federal courts no longer restrict unclean hands to equitable remedies or preserve the substantive version of the defense. It has also been assimilated into statutory law. The defense is additionally reproducing and multiplying into more distinctive doctrines, thus magnifying its impact. Despite its approval in the courts, the equitable defense of unclean hands has been largely disregarded or simply disparaged since the last century. Prior research on unclean hands divided the defense into topical areas of the law. Consistent with this approach, the conclusion reached was that it lacked cohesion and shared properties. This study sees things differently. It offers a common language to help avoid compartmentalization along with a unified framework to provide a more precise way of understanding the defense. Advancing an overarching theory and structure of the defense should better clarify not only when the doctrine should be allowed, but also why it may be applied differently in different circumstances. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1829 I. PHILOSOPHY OF EQUITY AND UNCLEAN HANDS ...................... 1837 * Copyright © 2018 T. Leigh Anenson. Professor of Business Law, University of Maryland; Associate Director, Center for the Study of Business Ethics, Regulation, and Crime; Of Counsel, Reminger Co., L.P.A; [email protected]. Thanks to the participants in the Discussion Group on the Law of Equity at the 2017 Southeastern Association of Law Schools Annual Conference, the 2017 International Academy of Legal Studies in Business Annual Conference, and the 2018 Pacific Southwest Academy of Legal Studies in Business Annual Conference. -

19-783 Van Buren V. United States (06/03/2021)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus VAN BUREN v. UNITED STATES CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT No. 19–783. Argued November 30, 2020—Decided June 3, 2021 Former Georgia police sergeant Nathan Van Buren used his patrol-car computer to access a law enforcement database to retrieve information about a particular license plate number in exchange for money. Alt- hough Van Buren used his own, valid credentials to perform the search, his conduct violated a department policy against obtaining da- tabase information for non-law-enforcement purposes. Unbeknownst to Van Buren, his actions were part of a Federal Bureau of Investiga- tion sting operation. Van Buren was charged with a felony violation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986 (CFAA), which subjects to criminal liability anyone who “intentionally accesses a computer without authorization or exceeds authorized access.” 18 U. S. C. §1030(a)(2). The term “exceeds authorized access” is defined to mean “to access a computer with authorization and to use such access to ob- tain or alter information in the computer that the accesser is not enti- tled so to obtain or alter.” §1030(e)(6).