The Chachalaca Volume 17 Number 3 September 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Near the Himalayas, from Kashmir to Sikkim, at Altitudes the Catholic Inquisition, and the Traditional Use of These of up to 2700 Meters

Year of edition: 2018 Authors of the text: Marc Aixalà & José Carlos Bouso Edition: Alex Verdaguer | Genís Oña | Kiko Castellanos Illustrations: Alba Teixidor EU Project: New Approaches in Harm Reduction Policies and Practices (NAHRPP) Special thanks to collaborators Alejandro Ponce (in Peyote report) and Eduardo Carchedi (in Kambó report). TECHNICAL REPORT ON PSYCHOACTIVE ETHNOBOTANICALS Volumes I - II - III ICEERS International Center for Ethnobotanical Education Research and Service INDEX SALVIA DIVINORUM 7 AMANITA MUSCARIA 13 DATURA STRAMONIUM 19 KRATOM 23 PEYOTE 29 BUFO ALVARIUS 37 PSILOCYBIN MUSHROOMS 43 IPOMOEA VIOLACEA 51 AYAHUASCA 57 IBOGA 67 KAMBÓ 73 SAN PEDRO 79 6 SALVIA DIVINORUM SALVIA DIVINORUM The effects of the Hierba Pastora have been used by Mazatec Indians since ancient times to treat diseases and for divinatory purposes. The psychoactive compound Salvia divinorum contains, Salvinorin A, is the most potent naturally occurring psychoactive substance known. BASIC INFO Ska Pastora has been used in divination and healing Salvia divinorum is a perennial plant native to the Maza- rituals, similar to psilocybin mushrooms. Maria Sabina tec areas of the Sierra Madre Oriental Mountains of Mexi- told Wasson and Hofmann (the discoverers of its Mazatec co. Its habitat is tropical forests, where it grows between usage) that Salvia divinorum was used in times when the- 300 and 800 meters above sea level. It belongs to the re was a shortage of mushrooms. Some sources that have Lamiaceae family, and is mainly reproduced by cuttings done later feldwork point out that the use of S. divinorum since it rarely produces seeds. may be more widespread than originally believed, even in times when mushrooms were abundant. -

Biological Opinion Regarding the Issuance of an Endangered Species Act of 1973, As Amended, (Act) Section 10(A)(1)(B) Permit

Biological Opinion for TE-065406-0 This document transmits the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's (Service) biological opinion regarding the issuance of an Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended, (Act) Section 10(a)(1)(B) permit. The federal action under consideration is the issuance of a permit authorizing the incidental take of the federally listed endangered Houston toad (Bufo houstonensis) under the authority of sections 10(a)(1)(B) and 10(a)(2) of the Act. Boy Scouts of America, Capitol Area Council No. 564 (BSA/CAC) has submitted an application for an incidental take permit under the Act for take of the Houston toad. An Environmental Assessment/Habitat Conservation Plan (EA/HCP) has been reviewed for mitigation acceptability. The implementing regulations for Section 10(a)(1)(B) of the Act, as provided for by 50 CFR 17.22, specify the criteria by which a permit allowing the incidental "take" of listed endangered species pursuant to otherwise lawful activities may be obtained. The purpose and need for the Section 10(a)(1)(B) permit is to ensure that incidental take resulting from the proposed construction and operation of a “High Adventure” camp on the 4,848-acre Griffith League Ranch in Bastrop County, Texas, will be minimized and mitigated to the maximum extent practicable, and that the take is not expected to appreciably reduce the likelihood of the survival and recovery of this federally listed endangered species in the wild or adversely modify or destroy its federally designated critical habitat. The two federally listed species identified within this EA/HCP include the endangered Houston toad (and its designated critical habitat) and the threatened bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). -

Информационный Сборник, № 32 Том II (Russian)

ПРАВИТЕЛЬСТВО МОСКВЫ ДЕПАРТАМЕНТ КУЛЬТУРЫ ГОРОДА МОСКВЫ GOVERNMENT OF MOSCOW MOSCOW DEPARTMENT OF CULTURE ЕВРОАЗИАТСКАЯ РЕГИОНАЛЬНАЯ АССОЦИАЦИЯ ЗООПАРКОВ И АКВАРИУМОВ EURASIAN REGIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS & AQUARIUMS МОСКОВСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ ЗООЛОГИЧЕСКИЙ ПАРК MOSCOW ZOO ИНФОРМАЦИОННЫЙ СБОРНИК ЕВРОАЗИАТСКОЙ РЕГИОНАЛЬНОЙ АССОЦИАЦИИ ЗООПАРКОВ И АКВАРИУМОВ INFORMATIONAL ISSUE OF EURASIAN REGIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS AND AQUARIUMS ВЫПУСК № 32 ISSUE № 32 МОСКВА 2013 2 3 ПРАВИТЕЛЬСТВО МОСКВЫ ДЕПАРТАМЕНТ КУЛЬТУРЫ ГОРОДА МОСКВЫ GOVERNMENT OF MOSCOW COMMITTEE FOR CULTURE ЕВРОАЗИАТСКАЯ РЕГИОНАЛЬНАЯ АССОЦИАЦИЯ ЗООПАРКОВ И АКВАРИУМОВ EURASIAN REGIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS & AQUARIUMS МОСКОВСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ ЗООЛОГИЧЕСКИЙ ПАРК MOSCOW ZOO ИНФОРМАЦИОННЫЙ СБОРНИК ЕВРОАЗИАТСКОЙ РЕГИОНАЛЬНОЙ АССОЦИАЦИИ ЗООПАРКОВ И АКВАРИУМОВ INFORMATIONAL ISSUE OF EURASIAN REGIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS AND AQUARIUMS ВЫПУСК № 32 ISSUE № 32 ТОМ II VOLUME II ________________ МОСКВА – 2013 – 4 5 В первом томе опубликованы сведения о зоопарках, аквариумах и питомниках – членах Евроазиатской региональной ассоциации зоопарков и аквариумов, а также о других зоологических учреждениях. Представлены материалы о деятельности ЕАРАЗА, отдельных зоопарков и информация о семинарах и совещаниях для работников зоопарков. Второй том содержит сведения о коллекциях и размножении животных в зоологических учреждениях. В приложении содержится информация о Красной Книге Международного Союза Охраны природы и природных ресурсов (МСОП) и Конвенции о международной торговле видами дикой фауны и -

Houston Toad PHVA (1994).Pdf

A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service in partial fulfillment of contract #94-172. The primary sponsors of this workshop were: The National Fish & Wildlife Foundation, the Lower Colorado River Authority, Horizon Environmental Services, Inc., The Texas Organization for Endangered Species, Espey, Houston & Associations, The Bastrop County Environmental Network, The City of Bastrop, Bastrop County, The National Audubon Society, The Sierra Club State Chapter, The Nature Conservancy, The Texas Forest Service, Texas Parks & Wildlife Department, National Wildlife Federation and the United States Fish & Wildlife Service. Cover Photo: Houston Toad (Bufo hustonensis) Provided by Bruce Stewart. Houston Toad Population & Habitat Viability Assessment Report. U.S. Seal (ed.). IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, Apple Valley, MN. 1994: 1-145. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. Send checks for US $35.00 (for printing and shipping costs) payable to CBSG; checks must be drawn on a US Bank. Visa and Mastercard also accepted. POPULATION AND HABITAT VIABILITY ASSESSMENT HOUSTON TOAD Bufo houstonensis U. S. Seal, Executive Editor Report of Workshop conducted by CBSG in partial fulfillment of USFWS Contract # 23-25 May 1994 Austin, Texas Houston Toad PHVA Report 2 Houston Toad PHVA Report 4 POPULATION AND HABITAT VIABILITY ASSESSMENT WORKSHOP HOUSTON TOAD Bufo houstonensis SECTION 1 PARTICIPANTS (Authors) & SPONSORS Houston Toad PHVA Report 5 Houston Toad PHVA Report 6 WORKSHOP PARTICIPANTS (Authors and Editors) Dede Armentrout Dee Ann Chamberlain National Audubon Society Lower Colorado River Authority Suite 301, 2525 Wallingwood P.O. -

Pharmaceutical Psychedelics

Psychedelics W I T H D A LT O N Gisel Murillo [ C O M P A N Y V I S I O N ] "To make the impossible possible. Dalton Pharma Services uses its scientific and pharmaceutical expertise to bring customer ideas to life. We develop their new drug products, optimize the synthesis of therapeutic candidates, and manufacture them at the highest level of quality." [ S E R V I C E S ] Contract Research Custom Synthesis Medicinal and Flow Chemistry API Process Development Formulation Development cGMP API Manufacturing cGMP Sterile Filling Analytical and Microbiology Services FDA inspected, HC approved, & MRA with EMA What are Psychedelics? Psychedelics Psychedelics are a subset of hallucinogenic drugs that alter mood, cognitive processes, and consciousness by influencing how neurotransmitters operate at the synapses of the central nervous system. The consumption of certain psychedelics may produce unpleasant, frightening, or pleasant visual and auditory hallucinations. [1] Some of the most well-known psychedelic drugs include LSD, peyote, psilocybin, and DMT. Psychedelics are controlled substances around various regulatory agencies due to their high potential for abuse. However, research has shown that psychedelics may play a role in treatments for psychiatric disorders. [1] Psilocybin is currently undergoing clinical studies for its potential to treat various conditions such as anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and problematic drug use. However, there are currently no approved therapeutic products containing psilocybin in Canada -

Chris Harper Private Lands Biologist U.S

Chris Harper Private Lands Biologist U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Austin Texas Ecological Services Office 512-490-0057 x 245 [email protected] http://www.fws.gov/partners/ U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service The Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program in Texas Voluntary Habitat Restoration on Private Lands • The Mission of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service: working with others to conserve, protect and enhance fish, wildlife, and plants and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people Federal Trust Species • The term “Federal trust species” means migratory birds, threatened species, endangered species, interjurisdictional fish, marine mammals, and other species of concern. • “Partners for Fish and Wildlife Act” (2006) • To authorize the Secretary of the Interior to provide technical and financial assistance to private landowners to restore, enhance, and manage private land to improve fish and wildlife habitats through the Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program. Habitat Restoration & Enhancement • Prescribed fire • Brush thinning • Grazing management • Tree planting • Native seed planting • Invasive species control • In-stream restoration • “Fish passage” • Wetlands Fire as a Driver of Vegetation Change • Climate X Fire Interactions • Climate X Grazing Interactions • Climate X Grazing X Fire • Historic effects • Time lags • Time functions • Climate-fuels-fire relationships • Fire regimes • Restoring fire-adapted ecosystems Woody encroachment Austin PFW • Houston Toad – Pine/oak savanna/woodlands • Southern Edwards Plateau -

Bulo Alvarius Girard 0Z 7

93.1 AMPHIBIA: SALIENTIA: BUFONIDAE BUFO ALVARIUS Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Wright (1949), Stebbins (1951, 1954, 1966), Bogert (1958), Blair (1959) and Cochran (1961b). Livezey and Wright FOUQUETTE,M. J., JR. 1970. Hulo alvarius. (1947) and Savage and Schuierer (1961) figured the eggs. Sonograms of calls were reproduced by Blair and Pettus Bulo alvarius Girard (1954) and Bogert (1960). Colorado River toad • DISTRIBUTION.Hulo alvarius ranges through southern Arizona and most of Sonora to at least seven miles west of Bulo alvarius Girard, 1859:26. Type-locality, "Valley of Gila Guamuchil, Sinaloa (Riemer, 1955). Hardy and McDiarmid and Colorado," restricted (Schmidt, 1953:61) to, "Colorado (1969) cite a record 20 miles north of Culiacan· but suggest River bottomlands below Yuma, Arizona; " modified this needs verification. Fouquette (1968) erred in reporting (Fouquette, 1968) to "Fort Yuma, Imperial County, Cali• the species in Nayarit; his reference should read "Sinaloa." fornia." Lectotype (= cotype, Cochran 1961a), U. S. Natl. The westernmost record for central Sonora is 9.4 miles east Mus. No. 2572, female; collected by Maj. G. H. Thomas, of HUlisabas (Wright, 1966). Malkin (1962) reported the 1855 (examined by author). toad from Tiburon Island. The only record for Baja California Phrynoidis alvarius: Cope, 1862:358. is 4.7 miles north of El Mayor (Brattstrom, 1951). California • CONTENT.No subspecies are recognized. records are restricted to bottomlands and irrigated areas of the Colorado delta region in Imperial County (Grinnell and • DEFINITION.Adults usually exceed 110 mm snout-to-vent, Camp, 1917; Storer, 1925; Slevin, 1928). Cole (1962) re• to at least 187 mm (Heringhi, 1969; Alamos, Sonora). -

TRACK LISTING Frog & Toad Calls of the Pacific Coast

Frog & Toad Calls of the Pacific Coast ISBN: 0-938027-14-X by Carlos Davidson Lab of Ornithology PLU # (CD: 91970), (CASS: 91735) TRACK LISTING TRACK COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME LOCATION 1 Couch's Spadefoot Scaphiopus couchi Maricopa Co., Arizona 2 Western Spadefoot Scaphiopus hammondi Butte Co., California 3 Great Basin Spadefoot Scaphiopus intermontanus Mono Co., California 4 Sonoran Desert Toad (Colorado River Toad) Bufo alvarius Maricopa Co., Arizona 5 Western Toad Bufo boreas San Diego Co., California; Skamania Co., Washington 6 Black Toad Bufo exsul Inyo Co., California 7 Yosemite Toad Bufo canorus Inyo Co., California; Mono Co., California 8 Woodhouse's Toad Bufo woodhousii Moffat Co., Colorado 9 Southwestern Toad Bufo microscaphus Santa Barbara Co., California 10 Red-spotted Toad Bufo punctatus Riverside Co., California 11 Great Plains Toad Bufo cognatus Cochise Co., Arizona 12 Pacific Chorus Frog (Pacific Treefrog) Pseudacris regilla (Hyla regilla) Riverside Co., California; Alameda Co., California; 13 California Treefrog Hyla cadaverina (Pseudacris cadaverina) Santa Barbara Co., California 14 Northern Red-legged Frog Rana aurora aurora Del Norte Co., California 14 California Red-legged Frog Rana aurora draytonii Marin Co., California 15 Wood Frog Rana sylvatica Tompkins Co., New York 16 Spotted Frog Rana pretiosa Okanogan Co., Washington 17 Cascade Frog Rana cascadae Jefferson Co., Oregon 18 Foothill Yellow-legged Frog Rana boylii Sonoma Co., California; Del Norte Co., California 19 Mountain Yellow-legged Frog (Sierra Nevada) Rana muscosa Yosemite National Park, California 19 Mountain Yellow-legged Frog (Southern Rana muscosa Riverside Co., California 20 Northern Leopard Frog Rana pipiens Ontario, Canada 21 Lowland Leopard Frog Rana yavapaiensis Maricopa Co., Arizona 22 Rio Grande Leopard Frog Rana berlandieri Yuma Co., Arizona 23 Bullfrog Rana catesbeiana Tompkins Co., New York; Bradley Co., Arkansas; Marin 25 Green Frog Rana clamitans Tompkins Co., New York 26 African Clawed Frog Xenopus laevis University of California, Berkeley, California. -

Copano Processing LP Final Biological

Biological Assessment Houston Central Gas Plant Expansion Project Colorado County, Texas Prepared for Copano Processing, L.P. Prepared by Whitenton Group, Inc. June 2012 Revised January 2013 3413 Hunter Road • San Marcos, Texas 78666 • office 512-353-3344 • fax 512-392-3450 www.whitentongroup.com Biological Assessment Houston Central Gas Plant Expansion Project Colorado County, Texas Prepared for Copano Processing, L.P. Sheridan, Texas Prepared by Whitenton Group, Inc. 3413 Hunter Road San Marcos, Texas 78666 WGI Project No. 1213 June 2012 Revised January 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................... II ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................. IV 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 3 3.0 AGENCY REGULATIONS ................................................................................................................. 5 3.1 REGULATIONS AND STANDARDS ........................................................................................... 5 3.2 ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT ..................................................................................................... 6 3.3 MIGRATORY BIRD -

Frogs and Toads of the Atchafalaya Basin

Frogs and Toads of the Atchafalaya Basin True Toads (Family Bufonidae) Microhylid Frogs and Toads Two true toads occur in the Atchafalaya Basin: (Family Microhylidae) True Toads Fowler’s Toad and the Gulf Coast Toad. Both The Eastern Narrow-Mouthed Toad is the Microhylid Frogs and Toads of these species are moderately sized and have only representative in the Atchafalaya Basin dry, warty skin. They have short hind limbs of this family. It is a plump frog with smooth and do not leap like other frogs, but rather skin, a pointed snout, and short limbs. There they make short hops to get around. They are is a fold of skin across the back of the head active primarily at night and use their short that can be moved forward to clear the hind limbs for burrowing into sandy soils eyes. They use this fold of skin especially during the day. They are the only two frogs when preying upon ants, a favorite food, to in the basin that lay long strings of eggs, as remove any attackers. Because of its plump opposed to clumps laid by other frog species. body and short limbs the male must secrete a Fowler’s Toad Gulf Coast Toad Both of these toad species possess enlarged sticky substance from a gland on its stomach Eastern Narrow-Mouthed Toad (Anaxyrus fowleri ) (Incilius nebulifer) glands at the back of the head that secrete a to stay attached to a female for successful (Gastrophryne carolinensis) white poison when attacked by a predator. mating; in most other frogs, the limbs are When handling these toads, one should avoid long enough to grasp around the female. -

Frogs and Toads of Northern Belize

Frogs, Toads, and Authors Frogs and Toads of Conservation Jenna M. Cole, Sarah K. Cooke, Venetia Northern Belize There are 35 species of frogs and S. Briggs-Gonzalez, Justin R. Dalaba, toads (38 amphibian species) and Frank J. Mazzotti recorded in Belize. Here we present some of the most common species found in and around Lamanai and the New River watershed. Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Frogs and toads have played an IFAS Publication WEC394 important role in ancient Maya edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw439 culture and can be seen in drawings May 2018 and figurines. Most species emerge with summer rains to breed and Photos courtesy of Mike Rochford males are often found calling in a and Michiko Squires, with assistance by Abdul Ramirez chorus in or near water. Females deposit eggs in or above water and Reference tadpoles develop into young frogs Lee, J.C. 2000. A field guide to the amphibians within a few weeks. and reptiles of the Maya world: the lowlands of Mexico, Northern Guatemala, and Belize. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York. Because they are tied to water to complete their life cycle, amphibians are indicators of ecosystem health. They are susceptible to pesticides (including repellants and perfumes), disease, and environmental pollution because of their semi-permeable For more information, contact: skin. There have been worldwide declines in amphibian populations as Lamanai Field Research Center a result of habitat destruction, Indian Church Village urbanization, and the increasing Orange Walk, Belize prevalence of chytrid fungus which is Tel: (501) 678-9785 lethal in some species and causes Email: [email protected] deformities in others. -

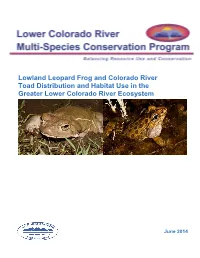

Lowland Leopard Frog and Colorado River Toad Distribution and Habitat Use in the Greater Lower Colorado River Ecosystem 2013

Lowland Leopard Frog and Colorado River Toad Distribution and Habitat Use in the Greater Lower Colorado River Ecosystem June 2014 Lower Colorado River Multi-Species Conservation Program Steering Committee Members Federal Participant Group California Participant Group Bureau of Reclamation California Department of Fish and Wildlife U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service City of Needles National Park Service Coachella Valley Water District Bureau of Land Management Colorado River Board of California Bureau of Indian Affairs Bard Water District Western Area Power Administration Imperial Irrigation District Los Angeles Department of Water and Power Palo Verde Irrigation District Arizona Participant Group San Diego County Water Authority Southern California Edison Company Arizona Department of Water Resources Southern California Public Power Authority Arizona Electric Power Cooperative, Inc. The Metropolitan Water District of Southern Arizona Game and Fish Department California Arizona Power Authority Central Arizona Water Conservation District Cibola Valley Irrigation and Drainage District Nevada Participant Group City of Bullhead City City of Lake Havasu City Colorado River Commission of Nevada City of Mesa Nevada Department of Wildlife City of Somerton Southern Nevada Water Authority City of Yuma Colorado River Commission Power Users Electrical District No. 3, Pinal County, Arizona Basic Water Company Golden Shores Water Conservation District Mohave County Water Authority Mohave Valley Irrigation and Drainage District Native American Participant Group Mohave Water Conservation District North Gila Valley Irrigation and Drainage District Hualapai Tribe Town of Fredonia Colorado River Indian Tribes Town of Thatcher Chemehuevi Indian Tribe Town of Wickenburg Salt River Project Agricultural Improvement and Power District Unit “B” Irrigation and Drainage District Conservation Participant Group Wellton-Mohawk Irrigation and Drainage District Yuma County Water Users’ Association Ducks Unlimited Yuma Irrigation District Lower Colorado River RC&D Area, Inc.