Joana Joachim, “'Embodiment and Subjectivity': Intersectional Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcript of Conversation Between Deanna Bowen, Pamela Edmonds, Selina Mudavanhu Mcmaster Museum of Art February 6, 2020

Transcript of Conversation between Deanna Bowen, Pamela Edmonds, Selina Mudavanhu McMaster Museum of Art February 6, 2020 Pamela Edmonds: Hi, I'm Pamela Edmonds, the new curator here at the MMA can everyone hear me okay? I'm not mic’d, but seems so. Thank you for joining us tonight, coming out in the bitter cold for tonight's event You know it's truly representing Black History Month, right? The coldest day, coldest month, but we're here to delve into and unpack some of the ideas around Deanna Bowen's incredible exhibition here, a Harlem Nocturne, which was curated by Kimberly Phillips of the Contemporary Art Gallery in Vancouver. And very happy to have Dr. Selina Mudavanhu here from McMaster Communication and Media Studies also and delve into some of the ideas around the exhibition and further on. And so, this exhibition will be touring going to next to Montreal then Halifax maybe others ... and Banff, which is very exciting. Firstly, I'd also like to recognize that we're gathered on the traditional tour of territories of the Mississauga and the Haudenosaunee nations and within the lands protected by the dish with one spoon wampum agreement. And I think also given the current moment in this country it's important, and I say dare I say urgent, to think about the ways that each of us are connected to land and space and place, whether we're settlers or not and how we can think about making the reality of Truth and Reconciliation real in all of our communities. -

BRENDAN FERNANDES B

BRENDAN FERNANDES b. 1979, Nairobi, Kenya lives and works in Chicago, IL Education 2006 – 2007 Whitney Museum oF American Art, Independent Study Program, New York, NY 2003 – 2005 The University oF Western Ontario, Master’s of Fine Arts in Visual Arts, London, ON 1998 – 2002 York University, Honors, Bachelor oF Fine Arts in Visual Arts, Toronto, ON Selected Solo Exhibitions 2021 Inaction…The Richmond Art Gallery. Richmond, BC In Pose. The Art Gallery in Ontario. Toronto, ON 2020 Art By Snapchat. Azienda SpecialePalaexpo. Rome, Italy. Brendan Fernandes: Bodily Forms, Chrysler Art Museum We Want a We, Pearlstein Gallery, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA In Action. Tarble Art Center, Eastern Illinos University, Charleston, IL 2019 Restrain, moniquemeloche, Chicago, IL In Action, Zilkha Gallery, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT (will travel to Tarble Arts Center, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, IL, 2020) Contract and Release, The Noguchi Museum, Long Island City, NY Call and Response, Museum oF Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL (perFormance series) Free Fall. The Richmond Art Gallery. Richmond, BC Free Fall 49. The Smithsonian American Art Museum. Washington, DC Ballet Kink. The Guggenheim Museum. New York, NY 2018 The Living Mask, DePaul University Art Museum, Chicago, IL On Flashing Lights, Nuit Blanche, Toronto, ON (performance) Open Encounter, The High Line, New York, NY (perFormance) The Master and Form, The Graham Foundation, Chicago, IL To Find a Forest, Art Gallery oF Greater Victoria, Victoria, BC (perFormance) SaFely (Sanctuary). FOR-SITE Foundation. San Francisco, CA 2017 Art by Snapchat, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL (performance) Move in Place, Anna Leonowens Gallery, NSCAD University, Halifax, NS Free Fall 49, The Getty, Los Angeles, CA (performance) From Hiz Hands, The Front, Eleven Twenty Projects, BuFFalo, NY I’M DOWN, 18th Street Arts Center, Santa Monica, CA Clean Labor, curated by Eric Shiner, Armory Fair, New York, NY (performance) Lost Bodies. -

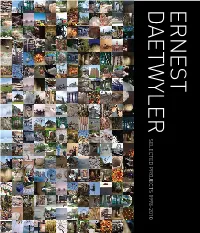

Selec Ted Pro Jec Ts 1998-2010

1 ERNEST LIFE IS BUT A DREAM DAETWYLER SELECTED PROJECTS 1998-2010 2 LIFE IS BUT A DREAM LIFE IS BUT A DREAM 4 LIFE IS BUT A DREAM LIFE IS BUT A DREAM 5 6 LIFE IS BUT A DREAM LIFE IS BUT A DREAM 7 UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED, ALL IMAGES BY ERNEST DAETWYLER. ERNEST DAETWYLER SELECTED PROJECTS 1998-2010 LIFE IS BUT A DREAM FOREWORD, Zhe Gu 12 LIFE IS BUT A DREAM 14 REALITY IN REVERSE [BARN RAISING] 26 STATIC UNCERTAINTY, Crystal Mowry 32 TEMPORALITY, POST PRODUCTION AND TRANSFORMATION, Corinna Ghaznavi 34 PASEWALK POLICE PHOENIX 42 SHELTER SPHERES 58 TIME BOMB 62 THE LUGGAGE PROJECT 68 LOVE SEAT 76 FURNISHING REFLECTIONS: DAETWYLER’S LOVE SEAT, Pamela Edmonds 78 FOREST CELL SPH[AIR]ES 80 ICE BUBBLES 84 FIRE ESCAPE [DOCENDO DISCIMUS] 88 BUBBLEMACHINE 90 BUBBLEMACHINE, Robert Freeman 96 DELETE? FRAGMENTS OF MEMORY 102 A STORM IS BLOWING FROM PARADISE, Corinna Ghaznavi 106 BIOGRAPHIES 116 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 118 LIST OF SELECTED PROJECTS 1998-2010 122 Zhe Gu FOREWORD It is a distinct pleasure, in conjunction with the exhibition life is but a dream and the launch of this compendium publication, to acknowledge the significant accomplishments of Swiss Canadian artist Ernest Daetwyler. The artist’s innovative and multi disciplinary approach has garnered significant acclaim and an international audience. The interactive and site-specific art created for life is but a dream transformed Gallery Stratford. Daetwyler’s sculptural works and time-based media inspired critical thought and reflection, and at the same time engaged the public with a sense of immediacy and playfulness. -

NATALIE WOOD Performing Change

PRIMARY EXHIBITION NATALIE WOOD Performing Change John B. Aird Gallery SEPTEMBER 2020 John B. Aird Gallery NATALIE WOOD | Performing Change PRIMARY EXHIBITION NATALIE WOOD Performing Change PRESENTED BY: The John B. Aird Gallery in partnership with Charles Street Video and Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival EXHIBITION DATES: September 10 - October 30, 2020 Originally planned for the annual Festival in May, this exhibition has been rescheduled due to COVID-19. The exhibition will be open to the public Wednesday to Friday 2 to 6 pm by appointment. AIRDGALLERY.ORG 906 Queen Street West, B05, Toronto Foreword BY JOWENNE CARPO HERRERA It is without surprise that today in this current socially and politically precarious world, Natalie continues to share her journey and work on first met Natalie Wood eighteen years ago during a brainstorming resistance and disruption of culturally defined normativity. Performing meeting about plans to participate in the annual Pride Toronto Pa- Change reflects Natalie’s lens-based work over the last decade and rein- I rade. Having recently moved into my first apartment in downtown forces the beauty of what is Black, and that queer love is love. Through Toronto (from my childhood suburban home in Scarborough), 2002 her experiences, her parents’ experiences and her grandparents’ expe- marked the year when my eyes first began to see the world in a different riences of colonial and racial injustices, Natalie shares how her identity lens. As a young queer person of colour, I felt a sense of belonging being relates to this society and how it is important to “perform change” — and surrounded by Black queer and other queer people of colour during our doing so requires self-love. -

Charmaine Andrea Nelson (Last Updated 4 December 2020)

Charmaine Andrea Nelson (last updated 4 December 2020) Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada e-mail: [email protected] Website: blackcanadianstudies.com Table of Contents Permanent Affiliations - 2 Education - 2 Major Research Awards, Fellowships & Honours - 3 Other Awards, Fellowships & Honours – 4 Research - 5 Research Grants and Scholarships - 5 Publications - 9 Lectures, Conferences, Workshops – 18 Keynote Lectures – 18 Invited Lectures: Academic Seminars, Series, Workshops – 20 Refereed Conference Papers - 29 Invited Lectures: Public Forums – 37 Museum & Gallery Lectures – 42 Course Lectures - 45 Teaching - 50 Courses - 50 Course Development - 59 Graduate Supervision and Service - 60 Administration/Service - 71 Interviews & Media Coverage – 71 Blogs & OpEds - 96 Interventions - 99 Conference, Speaker & Workshop Organization - 100 University/Academic Service: Appointments - 103 University/Academic Service: Administration - 104 Committee Service & Seminar Participation - 105 Forum Organization and Participation - 107 Extra-University Academic Service – 108 Qualifications, Training and Memberships - 115 Related Cultural Work Experience – 118 2 Permanent Affiliations 2020-present Department of Art History and Contemporary Culture NSCAD, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada Professor of Art History and Tier I Canada Research Chair in Transatlantic Black Diasporic Art and Community Engagement/ Founding Director - Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery: research, administrative duties, teaching (1 half course/ year): undergraduate and MA -

Vessna Perunovich

VESSNA PERUNOVICH EDUCATION 1985-1987 Academy of Fine Arts, University of Belgrade, Yugoslavia: MFA 1979-1984 Academy of Fine Arts, University of Belgrade, Yugoslavia: BFA SOLO EXHIBITIONS & SPECIAL PROJECTS 2019 Shifting Shelter, Illingworth Kerr Gallery, University Art Gallery, Calgary Alberta 2018 Not My Story, Angell Gallery, Toronto Ontario Shifting Shelter, Gallery Stratford, Stratford Ontario Far Away, So Close, Performance project, FAT Fashion Art Toronto 2017 Shifting Shelter, Angell Gallery, Toronto Ontario 2016 Politics of Movement, Center of Contemporary Art, Podgorica, Montenegro Politics of Movement, City Gallery Petkovic, Subotica Serbia Politics of Movement, Remont Art Association, Belgrade Serbia 2015 Mending Broken China, Angell Gallery, Toronto Ontario, Inteligensia Gallery, Beijing China Borders & Networks, Quebec tour: Atelier Silex, R3 University Gallery, Trois Rivieres Border Stitching, Oboro, Montreal, Quebec 2014 Seamless Crossings, MAI (Montreal Arts Intercultural), Montreal Quebec NETworks, Gallery MC NYC, New York USA 2013 Neither Here Nor There, touring exhibition Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa Ontario STILLS: Moments of Extreme Consequence, Angell Gallery, Toronto Ontario Line Rituals & Radical Knitting, Macdonald Stewart Art Centre, Guelph Ontario 2012 I Hug the World and the World Hugs Me Back, ongoing traveling performance project, New York US Border Stitching, Centre d’artistes Vaste et Vague, Carleton-sur-Mer, Quebec Neither Here Nor There, Tom Thomson Gallery, Owen Sound, Ontario 2011 Borderless, -

Museum Activism

MUSEUM ACTIVISM Only a decade ago, the notion that museums, galleries and heritage organisations might engage in activist practice, with explicit intent to act upon inequalities, injustices and environmental crises, was met with scepticism and often derision. Seeking to purposefully bring about social change was viewed by many within and beyond the museum community as inappropriately political and antithetical to fundamental professional values. Today, although the idea remains controversial, the way we think about the roles and responsibilities of museums as knowledge- based, social institutions is changing. Museum Activism examines the increasing significance of this activist trend in thinking and practice. At this crucial time in the evolution of museum thinking and practice, this ground-breaking volume brings together more than fifty contributors working across six continents to explore, analyse and critically reflect upon the museum’s relationship to activism. Including contribu- tions from practitioners, artists, activists and researchers, this wide-ranging examination of new and divergent expressions of the inherent power of museums as forces for good, and as activists in civil society, aims to encourage further experimentation and enrich the debate in this nascent and uncertain field of museum practice. Museum Activism elucidates the largely untapped potential for museums as key intellectual and civic resources to address inequalities, injustice and environmental challenges. This makes the book essential reading for scholars and students of museum and heritage studies, gallery studies, arts and heritage management, and politics. It will be a source of inspiration to museum practitioners and museum leaders around the globe. Robert R. Janes is a Visiting Fellow at the School of Museum Studies , University of Leicester, UK, Editor-in-Chief Emeritus of Museum Management and Curatorship, and the founder of the Coalition of Museums for Climate Justice. -

Always Moving Forward Contemporary African Photography from the Wedge Collection

Always Moving Forward Contemporary African Photography from the Wedge Collection Curated by Kenneth Montague gallery 44, toronto | Platform, winnipeg | Art Gallery of Peterborough Mohamed Bourouissa Always Moving Forward May 1 to 29, 2010 Contemporary African Photography Gallery 44 Mohamed Camara from the Wedge Collection Centre for Contemporary Photography 401 Richmond St. W, Suite 120 © 2010, Mohamed Bourouissa, Mohamed Toronto, ON M5V 3A8 Calvin Dondo Camara, Calvin Dondo, Samuel Fosso, November 3 to December 10, 2011 Hassan Hajjaj, Bouchra Khalili, Antony PLATFORM centre for Kimani, Lebohang Mashiloane, Aïda photographic + digital arts Muluneh, Dawit L. Petros, Zwelethu Samuel Fosso 121-100 Arthur St. Mthethwa, Guy Tillim, Andrew Winnipeg, MB R3B 1H3 Tshabangu, Nontsikelelo ‘Lolo’ Veleko, and Pamela Edmonds January 13 to March 4, 2012 Hassan Hajjaj curator Kenneth Montague Always Art Gallery of Peterborough exhibition coordinator Maria Kanellopoulos ISBN 978-0-9738294-9-5 250 Crescent St. Peterborough, ON K9J 2G1 All images courtesy of Dr Kenneth Montague / The Wedge Collection Bouchra Khalili Wedge Curatorial Projects would like to thank the artists, Moving as well as the following galleries: Essay Pamela Edmonds Mohamed Bourrissa | Galeries les filles du calvaire, Paris Antony Kimani managing editor Mohamed Camara | Galerie Pierre Brullé, Paris Alice Dixon Forward Calvin Dondo | Gallery MOMO, Johannesburg Lebohang Mashiloane copy Editors Samuel Fosso | Galerie Jean Marc Patras, Paris Alice Dixon, Gaye Jackson Hassan Hajjaj | Rose Issa, London / Third Line, Dubai Design Bouchra Khalili | Galerie of Marseille, Marseille Aïda Muluneh Zab Design & Typography Antony Kimani cover Lebohang Mashiloane Dawit L. Petros Zwelethu Mthethwa, Untitled, 2000 Zwelethu Mthethwa | Jack Shainman Gallery, New York Aïda Muluneh | Gallery MOMO, Johannesburg inside covers Dawit L. -

Report from the Undergraduate Curriculum and Calendar Committee

FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNDERGRADUATE CURRICULUM REPORT TO UNDERGRADUATE COUNCIL FOR THE 2020 CALENDAR NOVEMBER 2019 REPORT TO SENATE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES SUMMARY OF MAJOR CURRICULUM CHANGES FOR 2020-21 NEW PROGRAMS iARTS (Integrated Arts) Honours B.F.A. and Honours B.A. Programs (Appendix I) MAJOR REVISIONS None DELETION OF A PROGRAM None For a complete review of all changes, please refer to the November 2019 Faculty of Humanities Report to Undergraduate Council for changes to the 2020-2021 Undergraduate Calendar, found at http://www.humanities.mcmaster.ca/about/faculty-meetings/ - 1 - REPORT TO UNDERGRADUATE COUNCIL FACULTY OF HUMANITIES SUMMARY OF CURRICULUM CHANGES FOR 2020-21 This report highlights substantive changes being proposed. For a complete review of all changes, please refer to the November 2019 Faculty of Humanities Report to Undergraduate Council for changes to the 2020-2021 Undergraduate Calendar, found at http://www.humanities.mcmaster.ca/about/faculty-meetings/ 1. SCHOOL OF THE ARTS ● Proposed new program proposal: iARTS BFA and BA Programs (see Appendix I) • Studio Art: ○ Addition of course to optional list ○ Addition of 1 new course (ART 3VA3) • Art History: ○ Addition of 1 new course (ARTHIST 1PA3) ○ Minor revisions to 2 existing courses (ARTHIST 4AA3, 4X03) ○ Deletion of 1 course (ARTHIST 4H03) • Music: ○ Minor revision to Music 1 notes and requirements ○ Updating of all Music program lists ○ Addition of 1 new course (MUSIC 1CR3) ○ Minor revision to 30 courses (MUSIC 1CB3, 1EE6, 1GF3/2GF3/3GF3/4GF3, 1GW3/2GW3/3GW3/4GW3, 2B03, 2CA3, 2CB3, 2MC3, 2MH3, 2MT3, 2MU3, 2U03, 3JJ3, 3K03, 3KK3, 3L03, 3M03, 3N03, 3P03, 4K03, 4L03, 4M03, 4N03, MUSICCOG 3MP3) ○ Deletion of 2 courses (MUSIC 1CA3, 2CG3) • Theatre & Film Studies: ○ Addition of 2 new courses (THTRFLM 1H03, 2MM3) ○ Revision to 14 existing courses (THTRFLM 1T03, 2AA3, 2BB3, 2CP3, 3FF3, 3L03, 3P03, 3PR3, 3PS3, 3S06, 3VS3, 3WW3, 3XX3, 4D03) ○ Updating of course notes 2. -

COMMON THREAD a Project Proposal by Liesje Van Den Berk (NL) & Vessna Perunovich (CA /SR) & Sabine Oosterlynck (BE)

COMMON THREAD a project proposal by liesje van den berk (NL) & vessna perunovich (CA /SR) & sabine oosterlynck (BE) COMMON THREAD A project proposal by liesje van den berk (NL) & vessna perunovich (CA /SR) & sabine oosterlynck (BE) Liesje van den Berk Vessna Perunovich sabine oosterlynck Artists, sabine oosterlynck (Belgium), vessna perunovich (Canada /Serbia) and liesje van den berk (The Netherlands) met each other in Berlin, Germany during the Performance art studies PAS #20 “in context”. From the very beginning of their relationship they found a strong connection to each other both personally as well as through their respective art practices. They began the intense exchange of thoughts and ideas and from the onset, several strong connections become apparent in their work: the use of line and its trajectory, the notion of mobility, the use of space and the performative / process based approach to art making. Using materials such as elastic string, labels, tape and graphite to develop and create their artworks and performances, all three artists refer to the body and its connection to the site-specific character of the exhibiting space as well as to the context of larger social, cultural and political networks and relationships. Their proposed collaborative project ‘Common Thread’ intends to explore avenues of connectivity and participation as a way of making sense of the increasingly confusing, tenuous and divided world we live in. In their performance based research they are tracing and mapping a memory of displacements, presence, cultural interference and human interfaces. These interactions are reduced to simple materials as labels, thread, dust, void, bodies and lines. -

Uncovering Asian Canadian and Black Canadian Artistic Production

@ Ethnocultural Art Histories Research Uncovering Asian Canadian and Black Canadian Artistic Production 1 Acknowledgements The two exhibition and bibliographic projects which this catalogue accompanies could not have been completed without the attentive support of the knowledgeable staff at Artexte. Sincere thanks to the Artexte Research Residency Program and especially Artexte’s General and Artistic Director, Sarah Watson, for her constant encouragement of these projects and for giving us the chance to use Artexte’s space and resources to pursue this research. We also thank John Latour, Artexte’s Head Librarian, who gave us an excellent tour of the collection and provided important insights on how to effectively conduct research in Artexte’s holdings; and Jean-Philippe McGurrin, who helped us coordinate the early stages of our residency. The publication of this catalogue was made possible with generous support from Artexte, and The Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art and the Department of Art History at Concordia University. EAHR acknowledges the additional funding and support of Concordia University’s Faculty of Fine Arts Dean’s Discretionary Fund for the presentation of student work. A special thank you to our catalogue designer, Bryan Jim, for his expertise, patience and enthusiasm for the project. Finally, we would like to thank our Faculty Advisor, Dr. Alice Ming Wai Jim, for her earnest encouragement of our research and of our scholarly development. Dr. Jim’s edits to the catalogue essays were insightful and her constant drive and passion to advance ethnocultural art historical scholarship is truly inspirational. Ethnocultural Art Histories Research 2 EAHR @ ARTEXTE: Uncovering Asian Canadian and Black Canadian Artistic Production Introduction The Ethnocultural Art Histories Research group (EAHR) is a student-driven research community based in the Department of Art History at Concordia University. -

Artist's Curriculum Vitae

VESSNA PERUNOVICH EDUCATION 1985-1987 Academy of Fine Arts, University of Belgrade, Yugoslavia: MFA 1979-1984 Academy of Fine Arts, University of Belgrade, Yugoslavia: BFA SOLO EXHIBITIONS & SPECIAL PROJECTS 2019 Shifting Shelter, Illingworth Kerr Gallery, Alberta Collage of Art and Design, Calgary Alberta 2018 /19 Shifting Shelter, Gallery Stratford, Stratford Ontario 2018 Not My Story, Angell Gallery, Toronto Ontario Far Away, So Close, Performance project, FAT Fashion Art Toronto 2017 Shifting Shelter, Angell Gallery, Toronto Ontario 2016 Politics of Movement, Center of Contemporary Art, Podgorica, Montenegro Politics of Movement, City Gallery Petkovic, Subotica Serbia Politics of Movement, Remont Art Association, Belgrade Serbia 2015 Mending Broken China, Angell Gallery, Toronto Ontario Nothing to Wear, Performance project, FAT Fashion Art Toronto Borders & Networks, Quebec tour: Atelier Silex, R3 University Gallery, Trois Rivieres Border Stitching, Oboro, Montreal, Quebec 2014 Seamless Crossings, MAI (Montreal Arts Intercultural), Montreal Quebec 2013 Neither Here Nor There, touring exhibition Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa Ontario STILLS: Moments of Extreme Consequence, Angell Gallery, Toronto Ontario Line Rituals & Radical Knitting, Macdonald Stewart Art Centre, Guelph Ontario 2012 I Hug the World and the World Hugs Me Back, ongoing traveling performance project, New York USA Border Stitching, Centre d’artistes Vaste et Vague, Carleton-sur-Mer, Quebec Neither Here Nor There, Tom Thomson Gallery, Owen Sound, Ontario 2011 Borderless,