Lengthening a Tetrahedron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

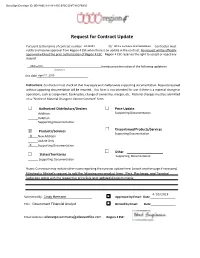

Request for Contract Update

DocuSign Envelope ID: 0E48A6C9-4184-4355-B75C-D9F791DFB905 Request for Contract Update Pursuant to the terms of contract number________________R142201 for _________________________ Office Furniture and Installation Contractor must notify and receive approval from Region 4 ESC when there is an update in the contract. No request will be officially approved without the prior authorization of Region 4 ESC. Region 4 ESC reserves the right to accept or reject any request. Allsteel Inc. hereby provides notice of the following update on (Contractor) this date April 17, 2019 . Instructions: Contractor must check all that may apply and shall provide supporting documentation. Requests received without supporting documentation will be returned. This form is not intended for use if there is a material change in operations, such as assignment, bankruptcy, change of ownership, merger, etc. Material changes must be submitted on a “Notice of Material Change to Vendor Contract” form. Authorized Distributors/Dealers Price Update Addition Supporting Documentation Deletion Supporting Documentation Discontinued Products/Services X Products/Services Supporting Documentation X New Addition Update Only X Supporting Documentation Other States/Territories Supporting Documentation Supporting Documentation Notes: Contractor may include other notes regarding the contract update here: (attach another page if necessary). Attached is Allsteel's request to add the following new product lines: Park, Recharge, and Townhall Collection along with the respective price -

![The Geometry of Nim Arxiv:1109.6712V1 [Math.CO] 30](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8642/the-geometry-of-nim-arxiv-1109-6712v1-math-co-30-48642.webp)

The Geometry of Nim Arxiv:1109.6712V1 [Math.CO] 30

The Geometry of Nim Kevin Gibbons Abstract We relate the Sierpinski triangle and the game of Nim. We begin by defining both a new high-dimensional analog of the Sierpinski triangle and a natural geometric interpretation of the losing positions in Nim, and then, in a new result, show that these are equivalent in each finite dimension. 0 Introduction The Sierpinski triangle (fig. 1) is one of the most recognizable figures in mathematics, and with good reason. It appears in everything from Pascal's Triangle to Conway's Game of Life. In fact, it has already been seen to be connected with the game of Nim, albeit in a very different manner than the one presented here [3]. A number of analogs have been discovered, such as the Menger sponge (fig. 2) and a three-dimensional version called a tetrix. We present, in the first section, a generalization in higher dimensions differing from the more typical simplex generalization. Rather, we define a discrete Sierpinski demihypercube, which in three dimensions coincides with the simplex generalization. In the second section, we briefly review Nim and the theory behind optimal play. As in all impartial games (games in which the possible moves depend only on the state of the game, and not on which of the two players is moving), all possible positions can be divided into two classes - those in which the next player to move can force a win, called N-positions, and those in which regardless of what the next player does the other player can force a win, called P -positions. -

Notes Has Not Been Formally Reviewed by the Lecturer

6.896 Topics in Algorithmic Game Theory February 22, 2010 Lecture 6 Lecturer: Constantinos Daskalakis Scribe: Jason Biddle, Debmalya Panigrahi NOTE: The content of these notes has not been formally reviewed by the lecturer. It is recommended that they are read critically. In our last lecture, we proved Nash's Theorem using Broweur's Fixed Point Theorem. We also showed Brouwer's Theorem via Sperner's Lemma in 2-d using a limiting argument to go from the discrete combinatorial problem to the topological one. In this lecture, we present a multidimensional generalization of the proof from last time. Our proof differs from those typically found in the literature. In particular, we will insist that each step of the proof be constructive. Using constructive arguments, we shall be able to pin down the complexity-theoretic nature of the proof and make the steps algorithmic in subsequent lectures. In the first part of our lecture, we present a framework for the multidimensional generalization of Sperner's Lemma. A Canonical Triangulation of the Hypercube • A Legal Coloring Rule • In the second part, we formally state Sperner's Lemma in n dimensions and prove it using the following constructive steps: Colored Envelope Construction • Definition of the Walk • Identification of the Starting Simplex • Direction of the Walk • 1 Framework Recall that in the 2-dimensional case we had a square which was divided into triangles. We had also defined a legal coloring scheme for the triangle vertices lying on the boundary of the square. Now let us extend those concepts to higher dimensions. 1.1 Canonical Triangulation of the Hypercube We begin by introducing the n-simplex as the n-dimensional analog of the triangle in 2 dimensions as shown in Figure 1. -

Interval Vector Polytopes

Interval Vector Polytopes By Gabriel Dorfsman-Hopkins SENIOR HONORS THESIS ROSA C. ORELLANA, ADVISOR DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS DARTMOUTH COLLEGE JUNE, 2013 Contents Abstract iv 1 Introduction 1 2 Preliminaries 4 2.1 Convex Polytopes . 4 2.2 Lattice Polytopes . 8 2.2.1 Ehrhart Theory . 10 2.3 Faces, Face Lattices and the Dual . 12 2.3.1 Faces of a Polytope . 12 2.3.2 The Face Lattice of a Polytope . 15 2.3.3 Duality . 18 2.4 Basic Graph Theory . 22 3IntervalVectorPolytopes 23 3.1 The Complete Interval Vector Polytope . 25 3.2 TheFixedIntervalVectorPolytope . 30 3.2.1 FlowDimensionGraphs . 31 4TheIntervalPyramid 38 ii 4.1 f-vector of the Interval Pyramid . 40 4.2 Volume of the Interval Pyramid . 45 4.3 Duality of the Interval Pyramid . 50 5 Open Questions 57 5.1 Generalized Interval Pyramid . 58 Bibliography 60 iii Abstract An interval vector is a 0, 1 -vector where all the ones appear consecutively. An { } interval vector polytope is the convex hull of a set of interval vectors in Rn.Westudy several classes of interval vector polytopes which exhibit interesting combinatorial- geometric properties. In particular, we study a class whose volumes are equal to the catalan numbers, another class whose legs always form a lattice basis for their affine space, and a third whose face numbers are given by the pascal 3-triangle. iv Chapter 1 Introduction An interval vector is a 0, 1 -vector in Rn such that the ones (if any) occur consecu- { } tively. These vectors can nicely and discretely model scheduling problems where they represent the length of an uninterrupted activity, and so understanding the combi- natorics of these vectors is useful in optimizing scheduling problems of continuous activities of certain lengths. -

Sequential Evolutionary Operations of Trigonometric Simplex Designs For

SEQUENTIAL EVOLUTIONARY OPERATIONS OF TRIGONOMETRIC SIMPLEX DESIGNS FOR HIGH-DIMENSIONAL UNCONSTRAINED OPTIMIZATION APPLICATIONS Hassan Musafer Under the Supervision of Dr. Ausif Mahmood DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOHPY IN COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING THE SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING UNIVERSITY OF BRIDGEPORT CONNECTICUT May, 2020 SEQUENTIAL EVOLUTIONARY OPERATIONS OF TRIGONOMETRIC SIMPLEX DESIGNS FOR HIGH-DIMENSIONAL UNCONSTRAINED OPTIMIZATION APPLICATIONS c Copyright by Hassan Musafer 2020 iii SEQUENTIAL EVOLUTIONARY OPERATIONS OF TRIGONOMETRIC SIMPLEX DESIGNS FOR HIGH-DIMENSIONAL UNCONSTRAINED OPTIMIZATION APPLICATIONS ABSTRACT This dissertation proposes a novel mathematical model for the Amoeba or the Nelder- Mead simplex optimization (NM) algorithm. The proposed Hassan NM (HNM) algorithm allows components of the reflected vertex to adapt to different operations, by breaking down the complex structure of the simplex into multiple triangular simplexes that work sequentially to optimize the individual components of mathematical functions. When the next formed simplex is characterized by different operations, it gives the simplex similar reflections to that of the NM algorithm, but with rotation through an angle determined by the collection of nonisometric features. As a consequence, the generating sequence of triangular simplexes is guaranteed that not only they have different shapes, but also they have different directions, to search the complex landscape of mathematical problems and to perform better performance than the traditional hyperplanes simplex. To test reliability, efficiency, and robustness, the proposed algorithm is examined on three areas of large- scale optimization categories: systems of nonlinear equations, nonlinear least squares, and unconstrained minimization. The experimental results confirmed that the new algorithm delivered better performance than the traditional NM algorithm, represented by a famous Matlab function, known as "fminsearch". -

Computing Invariants of Hyperbolic Coxeter Groups

LMS J. Comput. Math. 18 (1) (2015) 754{773 C 2015 Author doi:10.1112/S1461157015000273 CoxIter { Computing invariants of hyperbolic Coxeter groups R. Guglielmetti Abstract CoxIter is a computer program designed to compute invariants of hyperbolic Coxeter groups. Given such a group, the program determines whether it is cocompact or of finite covolume, whether it is arithmetic in the non-cocompact case, and whether it provides the Euler characteristic and the combinatorial structure of the associated fundamental polyhedron. The aim of this paper is to present the theoretical background for the program. The source code is available online as supplementary material with the published article and on the author's website (http://coxiter.rgug.ch). Supplementarymaterialsareavailablewiththisarticle. Introduction Let Hn be the hyperbolic n-space, and let Isom Hn be the group of isometries of Hn. For a given discrete hyperbolic Coxeter group Γ < Isom Hn and its associated fundamental polyhedron P ⊂ Hn, we are interested in geometrical and combinatorial properties of P . We want to know whether P is compact, has finite volume and, if the answer is yes, what its volume is. We also want to find the combinatorial structure of P , namely, the number of vertices, edges, 2-faces, and so on. Finally, it is interesting to find out whether Γ is arithmetic, that is, if Γ is commensurable to the reflection group of the automorphism group of a quadratic form of signature (n; 1). Most of these questions can be answered by studying finite and affine subgroups of Γ, but this involves a huge number of computations. -

The Hippo Pathway Component Wwc2 Is a Key Regulator of Embryonic Development and Angiogenesis in Mice Anke Hermann1,Guangmingwu2, Pavel I

Hermann et al. Cell Death and Disease (2021) 12:117 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-021-03409-0 Cell Death & Disease ARTICLE Open Access The Hippo pathway component Wwc2 is a key regulator of embryonic development and angiogenesis in mice Anke Hermann1,GuangmingWu2, Pavel I. Nedvetsky1,ViktoriaC.Brücher3, Charlotte Egbring3, Jakob Bonse1, Verena Höffken1, Dirk Oliver Wennmann1, Matthias Marks4,MichaelP.Krahn 1,HansSchöler5,PeterHeiduschka3, Hermann Pavenstädt1 and Joachim Kremerskothen1 Abstract The WW-and-C2-domain-containing (WWC) protein family is involved in the regulation of cell differentiation, cell proliferation, and organ growth control. As upstream components of the Hippo signaling pathway, WWC proteins activate the Large tumor suppressor (LATS) kinase that in turn phosphorylates Yes-associated protein (YAP) and its paralog Transcriptional coactivator-with-PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) preventing their nuclear import and transcriptional activity. Inhibition of WWC expression leads to downregulation of the Hippo pathway, increased expression of YAP/ TAZ target genes and enhanced organ growth. In mice, a ubiquitous Wwc1 knockout (KO) induces a mild neurological phenotype with no impact on embryogenesis or organ growth. In contrast, we could show here that ubiquitous deletion of Wwc2 in mice leads to early embryonic lethality. Wwc2 KO embryos display growth retardation, a disturbed placenta development, impaired vascularization, and finally embryonic death. A whole-transcriptome analysis of embryos lacking Wwc2 revealed a massive deregulation of gene expression with impact on cell fate determination, 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; cell metabolism, and angiogenesis. Consequently, a perinatal, endothelial-specific Wwc2 KO in mice led to disturbed vessel formation and vascular hypersprouting in the retina. -

Arxiv:1705.01294V1

Branes and Polytopes Luca Romano email address: [email protected] ABSTRACT We investigate the hierarchies of half-supersymmetric branes in maximal supergravity theories. By studying the action of the Weyl group of the U-duality group of maximal supergravities we discover a set of universal algebraic rules describing the number of independent 1/2-BPS p-branes, rank by rank, in any dimension. We show that these relations describe the symmetries of certain families of uniform polytopes. This induces a correspondence between half-supersymmetric branes and vertices of opportune uniform polytopes. We show that half-supersymmetric 0-, 1- and 2-branes are in correspondence with the vertices of the k21, 2k1 and 1k2 families of uniform polytopes, respectively, while 3-branes correspond to the vertices of the rectified version of the 2k1 family. For 4-branes and higher rank solutions we find a general behavior. The interpretation of half- supersymmetric solutions as vertices of uniform polytopes reveals some intriguing aspects. One of the most relevant is a triality relation between 0-, 1- and 2-branes. arXiv:1705.01294v1 [hep-th] 3 May 2017 Contents Introduction 2 1 Coxeter Group and Weyl Group 3 1.1 WeylGroup........................................ 6 2 Branes in E11 7 3 Algebraic Structures Behind Half-Supersymmetric Branes 12 4 Branes ad Polytopes 15 Conclusions 27 A Polytopes 30 B Petrie Polygons 30 1 Introduction Since their discovery branes gained a prominent role in the analysis of M-theories and du- alities [1]. One of the most important class of branes consists in Dirichlet branes, or D-branes. D-branes appear in string theory as boundary terms for open strings with mixed Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions and, due to their tension, scaling with a negative power of the string cou- pling constant, they are non-perturbative objects [2]. -

Physical Interpretation of the 30 8-Simplexes in the E8 240-Polytope

Physical Interpretation of the 30 8-simplexes in the E8 240-Polytope: Frank Dodd (Tony) Smith, Jr. 2017 - viXra 1702.0058 248-dim Lie Group E8 has 240 Root Vectors arranged on a 7-sphere S7 in 8-dim space. The 12 vertices of a cuboctahedron live on a 2-sphere S2 in 3-dim space. They are also the 4x3 = 12 outer vertices of 4 tetrahedra (3-simplexes) that share one inner vertex at the center of the cuboctahedron. This paper explores how the 240 vertices of the E8 Polytope in 8-dim space are related to the 30x8 = 240 outer vertices (red in figure below) of 30 8-simplexes whose 9th vertex is a shared inner vertex (yellow in figure below) at the center of the E8 Polytope. The 8-simplex has 9 vertices, 36 edges, 84 triangles, 126 tetrahedron cells, 126 4-simplex faces, 84 5-simplex faces, 36 6-simplex faces, 9 7-simplex faces, and 1 8-dim volume The real 4_21 Witting polytope of the E8 lattice in R8 has 240 vertices; 6,720 edges; 60,480 triangular faces; 241,920 tetrahedra; 483,840 4-simplexes; 483,840 5-simplexes 4_00; 138,240 + 69,120 6-simplexes 4_10 and 4_01; and 17,280 = 2,160x8 7-simplexes 4_20 and 2,160 7-cross-polytopes 4_11. The cuboctahedron corresponds by Jitterbug Transformation to the icosahedron. The 20 2-dim faces of an icosahedon in 3-dim space (image from spacesymmetrystructure.wordpress.com) are also the 20 outer faces of 20 not-exactly-regular-in-3-dim tetrahedra (3-simplexes) that share one inner vertex at the center of the icosahedron, but that correspondence does not extend to the case of 8-simplexes in an E8 polytope, whose faces are both 7-simplexes and 7-cross-polytopes, similar to the cubocahedron, but not its Jitterbug-transform icosahedron with only triangle = 2-simplex faces. -

15 BASIC PROPERTIES of CONVEX POLYTOPES Martin Henk, J¨Urgenrichter-Gebert, and G¨Unterm

15 BASIC PROPERTIES OF CONVEX POLYTOPES Martin Henk, J¨urgenRichter-Gebert, and G¨unterM. Ziegler INTRODUCTION Convex polytopes are fundamental geometric objects that have been investigated since antiquity. The beauty of their theory is nowadays complemented by their im- portance for many other mathematical subjects, ranging from integration theory, algebraic topology, and algebraic geometry to linear and combinatorial optimiza- tion. In this chapter we try to give a short introduction, provide a sketch of \what polytopes look like" and \how they behave," with many explicit examples, and briefly state some main results (where further details are given in subsequent chap- ters of this Handbook). We concentrate on two main topics: • Combinatorial properties: faces (vertices, edges, . , facets) of polytopes and their relations, with special treatments of the classes of low-dimensional poly- topes and of polytopes \with few vertices;" • Geometric properties: volume and surface area, mixed volumes, and quer- massintegrals, including explicit formulas for the cases of the regular simplices, cubes, and cross-polytopes. We refer to Gr¨unbaum [Gr¨u67]for a comprehensive view of polytope theory, and to Ziegler [Zie95] respectively to Gruber [Gru07] and Schneider [Sch14] for detailed treatments of the combinatorial and of the convex geometric aspects of polytope theory. 15.1 COMBINATORIAL STRUCTURE GLOSSARY d V-polytope: The convex hull of a finite set X = fx1; : : : ; xng of points in R , n n X i X P = conv(X) := λix λ1; : : : ; λn ≥ 0; λi = 1 : i=1 i=1 H-polytope: The solution set of a finite system of linear inequalities, d T P = P (A; b) := x 2 R j ai x ≤ bi for 1 ≤ i ≤ m ; with the extra condition that the set of solutions is bounded, that is, such that m×d there is a constant N such that jjxjj ≤ N holds for all x 2 P . -

Frequently Asked Questions in Polyhedral Computation

Frequently Asked Questions in Polyhedral Computation http://www.ifor.math.ethz.ch/~fukuda/polyfaq/polyfaq.html Komei Fukuda Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne and Zurich, Switzerland [email protected] Version June 18, 2004 Contents 1 What is Polyhedral Computation FAQ? 2 2 Convex Polyhedron 3 2.1 What is convex polytope/polyhedron? . 3 2.2 What are the faces of a convex polytope/polyhedron? . 3 2.3 What is the face lattice of a convex polytope . 4 2.4 What is a dual of a convex polytope? . 4 2.5 What is simplex? . 4 2.6 What is cube/hypercube/cross polytope? . 5 2.7 What is simple/simplicial polytope? . 5 2.8 What is 0-1 polytope? . 5 2.9 What is the best upper bound of the numbers of k-dimensional faces of a d- polytope with n vertices? . 5 2.10 What is convex hull? What is the convex hull problem? . 6 2.11 What is the Minkowski-Weyl theorem for convex polyhedra? . 6 2.12 What is the vertex enumeration problem, and what is the facet enumeration problem? . 7 1 2.13 How can one enumerate all faces of a convex polyhedron? . 7 2.14 What computer models are appropriate for the polyhedral computation? . 8 2.15 How do we measure the complexity of a convex hull algorithm? . 8 2.16 How many facets does the average polytope with n vertices in Rd have? . 9 2.17 How many facets can a 0-1 polytope with n vertices in Rd have? . 10 2.18 How hard is it to verify that an H-polyhedron PH and a V-polyhedron PV are equal? . -

Sampling Uniformly from the Unit Simplex

Sampling Uniformly from the Unit Simplex Noah A. Smith and Roy W. Tromble Department of Computer Science / Center for Language and Speech Processing Johns Hopkins University {nasmith, royt}@cs.jhu.edu August 2004 Abstract We address the problem of selecting a point from a unit simplex, uniformly at random. This problem is important, for instance, when random multinomial probability distributions are required. We show that a previously proposed algorithm is incorrect, and demonstrate a corrected algorithm. 1 Introduction Suppose we wish to select a multinomial distribution over n events, and we wish to do so uniformly n across the space of such distributions. Such a distribution is characterized by a vector ~p ∈ R such that n X pi = 1 (1) i=1 and pi ≥ 0, ∀i ∈ {1, 2, ..., n} (2) n In practice, of course, we cannot sample from R or even an interval in R; computers have only finite precision. One familiar technique for random generation in real intervals is to select a random integer and normalize it within the desired interval. This easily solves the problem when n = 2; select an integer x uniformly from among {0, 1, 2, ..., M} (where M is, perhaps, the largest integer x x that can be represented), and then let p1 = M and p2 = 1 − M . What does it mean to sample uniformly under this kind of scheme? There are clearly M + 1 discrete distributions from which we sample, each corresponding to a choice of x. If we sample x uniformly from {0, 1, ..., M}, then then we have equal probability of choosing any of these M + 1 distributions.