Massachusetts Association of School Superintendents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exam School Task Force Recommendation

Exam School Task Force Recommendation Co-Chairs: Tanisha M. Sullivan and Michael Contompasis Superintendent Dr. Brenda Cassellius 6.30.21 Task Force Charge Building upon the work initiated by the Superintendent’s Exam Schools Admissions Criteria Working Group, the Boston School Committee Exam Schools Admissions Task Force is charged with developing a set of recommendations for the admissions policy for Boston Public Schools exam schools. The desired outcome is to expand the applicant pool and create an admissions process that will support student enrollment at each of the exam schools such that rigor is maintained and the student body better reflects the racial, socioeconomic, and geographic diversity of all students (K-12) in the city of Boston. The Task Force shall consider use of the new NWEA assessment and other factors, and leverage learning from a full review of the implementation of the SY 21-22 admissions criteria, as well as a thorough review of practices in other districts. 2 What are we accomplishing tonight: What are we trying to achieve? Develop a recommendation for the exam school admissions process that: ● Maintains rigor ● Increases geographical, socioeconomic, and racial diversity How will we do this? What is the task force considering? 1. Eligibility 2. Invitations What are we discussing tonight? The formal recommendation from the task force that is supported by the Superintendent on the admissions criteria and process for Boston’s three exam schools. 3 Task Force Members ● Co-Chair, Michael Contompasis, former Boston Latin School Head of School and former BPS Superintendent ● Co-Chair, Tanisha M. Sullivan, Esq., President, NAACP Boston Branch and former BPS Chief Equity Officer ● Pastor Samuel Acevedo, Co-Chair, Opportunity and Achievement Gaps Task Force ● Acacia Aguirre, parent, John D. -

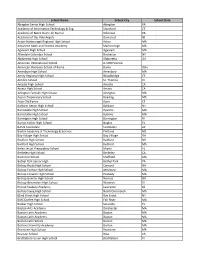

Participating School List 2018-2019

School Name School City School State Abington Senior High School Abington PA Academy of Information Technology & Eng. Stamford CT Academy of Notre Dame de Namur Villanova PA Academy of the Holy Angels Demarest NJ Acton-Boxborough Regional High School Acton MA Advanced Math and Science Academy Marlborough MA Agawam High School Agawam MA Allendale Columbia School Rochester NY Alpharetta High School Alpharetta GA American International School A-1090 Vienna American Overseas School of Rome Rome Italy Amesbury High School Amesbury MA Amity Regional High School Woodbridge CT Antilles School St. Thomas VI Arcadia High School Arcadia CA Arcata High School Arcata CA Arlington Catholic High School Arlington MA Austin Preparatory School Reading MA Avon Old Farms Avon CT Baldwin Senior High School Baldwin NY Barnstable High School Hyannis MA Barnstable High School Hyannis MA Barrington High School Barrington RI Barron Collier High School Naples FL BASIS Scottsdale Scottsdale AZ Baxter Academy of Technology & Science Portland ME Bay Village High School Bay Village OH Bedford High School Bedford NH Bedford High School Bedford MA Belen Jesuit Preparatory School Miami FL Berkeley High School Berkeley CA Berkshire School Sheffield MA Bethel Park Senior High Bethel Park PA Bishop Brady High School Concord NH Bishop Feehan High School Attleboro MA Bishop Fenwick High School Peabody MA Bishop Guertin High School Nashua NH Bishop Hendricken High School Warwick RI Bishop Seabury Academy Lawrence KS Bishop Stang High School North Dartmouth MA Blind Brook High -

Massachusetts State Equity Plan 2015-2019

ESE Strategic Plan Massachusetts State Equity Plan 2015-2019 August 7, 2015 Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education 75 Pleasant Street, Malden,Office MA 02148 of Planning,-4906 Research, and Delivery Systems Phone 781-338-3000 TTY:November N.E.T. Relay 2014 800- 439-2370 www.doe.mass.edu PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK TO ALLOW FOR DOUBLE-SIDED COPYING MA Department of Elementary & Secondary Education, 1 Table of Contents Section 1: Introduction .................................................................................................................... 4 Section 2: Stakeholder Engagement .............................................................................................. 10 Section 3: Definitions ..................................................................................................................... 12 Section 4: Identified Equity Gaps ................................................................................................... 16 Equity Gap 1: Educator Experience ......................................................................................... 17 Root Causes of Equity Gap 1: Educator Experience ................................................................ 19 Equity Gap 2: Educator Preparation ........................................................................................ 20 Root Causes of Equity Gap 2: Educator Preparation ............................................................... 22 Equity Gap 3: Educator Effectiveness ..................................................................................... -

BPS at a Glance 19 Final.Pdf

Boston Public Schools at a Glance Published by2018–2019 the BPS Communications Office | Revised November, 2018 OUR MISSION BPS STRATEGIC PRIORITIES THE ESSENTIALS As the birthplace of public education in this nation, the Late September, 2018, Laura Perille presented strategic The BPS Essentials for Instructional Equity establishes a Boston Public Schools is committed to transforming the priorities to the School Committee. coherent, research-based vision of instruction and related Establish the lives of all children through exemplary teaching in a 1. Improve Opportunities for Students. competencies. This initiative is intended to help close systemic conditions necessary to improve opportunities opportunity and achievement gaps with inclusive, rigorous, world-class system of innovative and welcoming schools. for students in order to narrow achievement gaps at all and culturally and linguistically sustaining instructional We partner with the community, families, and students BPS schools. programs. It focuses on the whole child to ensure that to develop within every learner the knowledge, skill, and 2. Differentiate School Supports. Position Central when BPS students graduate, they are ready for college, character to excel in college, career, and life. Office to enable rapid and sustainable improvement to career, and life. There are resources, tools, and professional teaching and learning in all schools while prioritizing learning opportunities that school teams and individual supports to lower performing schools. SCHOOLS & STUDENTS educators can draw upon. 3. Plan for the Future. Align long-term investment The competencies comprising the BPS Essentials for There are 125 schools in BPS: decisions of BuildBPS around new or improved Instructional Equity are: 7 schools for early learners facilities with decisions about grade configurations, 1. -

The Normal Offering 1917

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Bridgewater State Yearbooks Campus Journals and Publications 1917 The orN mal Offering 1917 Bridgewater State Normal School Recommended Citation Bridgewater State Normal School. (1917). The Normal Offering 1917. Retrieved from: http://vc.bridgew.edu/yearbooks/25 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. R"& NORMAL OFFERING VOLUME XVIX A year book published by the students of the Bridgewater Normal School under the direction of an Editorial Board chosen by the student body. Price, - - - One Dollar and a Quarter Address Richmond Barton, Bridgewater Normal School, Bridgewater, Mass. Orders for 1918 Offering should be placed with Business Manager on or before February 1, 1918. Printed by Arthur H. Willis, Bridgewater, - Massachusetts. o ®0 Ultam 1. ilarkaon for mang pars our trarljrr anb altuags our frtrttfc, ®I|ts hook is fofttratrfL (Eotttettta Alumni, ........ 28 A Misinterpretation, ....... 98 Athletics: Tennis Club, ....... 94 Athletic Association, . .94 Football, ....... 95 Baseball, ........ 97 Basketball, ....... 99 Clara Coffin Prince, . .20 Commencement Week, ...... 25 Contents, . .6 Dedication, ....... 5 Editorial Board, . .23 Editorial, ........ 24 Faculty, ........ 9 Faculty Notes, ... ... 16 Histories: Class A, . .40 Class B., . 42 Class K. -P., 48 Seniors, . 53 Specials, ........ 71 Olass \j, . Id Juniors, ........ 78 Hon. George H. Martin, ...... 18 Kappa Delta Phi Fraternity Play, . 101 Kappa Delta Phi, ....... 103 Normal Clubs, ....... 31 NORMAL OFFERING 7 Organizations: Dramatic Club, . • . 87 Glee Club, ....... 89 Y. P. U., 91 Woodward Hall Association, . .92 Robert E. Pellissier, ...... 20 Sororities: Lambda Phi, ........ 105 Alpha Gamma Phi, ...... 107 Tau Beta Gamma, . -

EPFP Fellows

EPFP Fellows EPFP fellows come from a variety of organizations—government, non-profit and for-profit—and bring different perspectives to our discussion of educational leadership and policy. 2017-2018 Fellows Tinu Akinfolarin, Human Capital Manager Marisa Mendonsa, Principal Boston Public Schools Mohawk Trail Regional School Tess Atkinson, Deputy Director of External Affairs Jennifer Metsch, Graduate Student, Social Work Boston Public Schools University of Connecticut Kevin Brill, Boston Big Picture School Adrienne Murphy, Senior Policy Analyst Boston Public Schools MA Dept of Elementary and Secondary Education Sinead Chalmers, Research and Policy Analyst Clara O’Rourke, Director of Programs and Evaluation Rennie Center for Education Research & Policy Latino Education Institute/Worcester Public Schools Elizabeth Chmielewski, Senior Consultant Ray Porch, Manager of Diversity Programs Public Consulting Group Boston Public Schools Moira Connolly, Coordinator for Massachusetts Brenda Rodriguez, Chief Financial Officer Expanded Learning Time Big Picture Learning MA Dept of Elementary and Secondary Education Fran Rosenberg, Executive Director Alyssa Corrigan, Policy & Communications Manager Northshore Education Consortium Empower Schools Jenn Scott, Boston Program Manager Kristen Daley, Director of Special Projects & Initiatives A-List Education Boston Public Schools Eric Stevens, Data Analyst, Office of Human Capital Beth Dowd, Dean of Operations Boston Public Schools Blackstone Valley Prep Mayoral Academy Aaron Stone, High School Biology Teacher Sam Fell, Management Development Associate Boston Day and Evening Academy Curriculum Associates Cidhinnia M. Torres Campos, Director of Institutional Jennifer Gaudet, Assistant Superintendent for Effectiveness Curriculum, Instruction and Assessment Wentworth Institute of Technology Maynard Public Schools Abby Van Dam, Special Education Inclusion Teacher Liz Harris, Research and Assessment Associate UP Academy Holland Wentworth Institute of Technology Carmen N. -

MASSACHUSETTS TEACHERS' RETIREMENT SYSTEM Schedule of Nonemployer Allocations and Schedule of Collective Pension Amounts June 30

MASSACHUSETTS TEACHERS'RETIREMENT SYSTEM Schedule of Nonemployer Allocations and Schedule of Collective Pension Amounts June 30, 2016 (With Independent Auditors' Report Thereon) KPMG LLP Two Financial Center 60 South Street Boston, MA 02111 Independent Auditors' Report Mr. Thomas G. Shack III, Comptroller Commonwealth of Massachusetts: We have audited the accompanying schedule of nonemployer allocations of the Massachusetts Teachers' Retirement System (MTRS) as of and for the year ended June 30, 2016, and the related notes. We have also audited the columns titled net pension liability, total deferred outflows of resources, total deferred inflows of resources, and total nonemploy.er pension expense (specified column totals) included in the accompanying schedule of collective pension amounts of MTRS as of and for the year ended June 30, 2016, and the related notes. Management's Responsibility for the Schedules Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these schedules in accordance with U.S. generally accepted accounting principles; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of the schedules that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Auditors' Responsibility Our responsibility is to express opinions on the schedule of nonemployer allocations and the specified column totals included in the schedule of collective pension amounts based on our audit. We conducted our audit in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the schedule of nonemployer allocations and the specified column totals included in the schedule of collective pension amounts are free from material misstatement. -

Bishop Feehan High School Cardinal Spellman High School Mansfield High School New Bedford High School Norwood High School Seekonk High School Silver Lake Reg

High Art 2021 Dreamscapes May 18– June 3 Nine Massachusetts high schools have created mural art beyond your wildest dreams for the Attleboro Arts Museum’s annual High Art Exhibition held in-gallery and online from May 18th- June 3rd, 2021. High Art connects teens with artists both past and present, fosters the creation of original artworks, and provides a professional forum for students to voice their creativity and work collaboratively. This year’s High Art theme of DREAMSCAPES features visual expressions of the surreal that are free from conscious, clear or controlled thoughts. Dreamscapes place value on the articulation of imaginative visions, the bizarre of the subconscious and find beauty in the unconventional. 2021 High School Participants: Attleboro High School Bishop Feehan High School Cardinal Spellman High School Mansfield High School New Bedford High School Norwood High School Seekonk High School Silver Lake Reg. High School Taunton High School Merit Award Attleboro High School Subconscious Realities Every night when we fall asleep, our bodies are at rest, but our minds go on a journey to places unknown. The Surrealistic visions of our dreams could lean towards a direction of darker, nightmarish realities, while others could create playful or even futuristic visions. All pieces in this installation are unified by the inclusion of the moon, which can be viewed from anywhere on planet Earth, in varying stages of its waxing and waning cycles throughout the month. Although each individual Dreamscape painting is created with a different monochromatic color scheme, the arrangement of the pieces together, by order of the color wheel, keep cohesion among the pieces and provide a direction for the viewer’s eye to follow. -

THE JOSEPH LEE K-8 SCHOOL 155 Talbot Avenue, Dorchester, MA 02124 Tel: 617.635.8687 • Fax: 617.635.8692

THE JOSEPH LEE K-8 SCHOOL 155 Talbot Avenue, Dorchester, MA 02124 Tel: 617.635.8687 • Fax: 617.635.8692 FAMILY & STUDENT HANDBOOK 2019 – 2020 2 Table of Contents Principal’s Welcome 5 Our Mission and Vision 6 Core Values 7 Regular School & Early Dismissal Hours 8 Leadership Team 9 Visiting The School 10 Getting To The School 11 Programs 12 Social Emotional Support & Services 14 General Policies and Procedures 16 Transportation Procedures & Expectations 17 Personal Cell Phone & Technology Policies 20 Team Wear Policy 21 Locker Policy 23 Anti-Bullying Resources 24 Student Support Office (SSO) 25 Emergency Procedures 26 School-Wide Classroom Policies and Procedures 27 Student Support Team 28 Homework & Academic Honesty Policy 29 Assessments, Progress Reports, Warning Notices, Promotion Requirements 31 Family Communication & Engagement 34 School Parent Council 35 Family Resources 36 Social Media Tips for Parents 37 3 4 Principal’s Welcome A Letter from Principal Crowley Dear Joseph Lee Families, Welcome to another exciting year at the Joseph Lee School! This handbook is written for your family and is intended to serve as a guide to life at our school. We hope it will help orient you, and help you feel a part of our enriching learning community. In the following pages, you will find a description of our school’s vision and mission, our academic requirements and general policies, as well as the commitments that we ask of staff, students, and their parents/guardians. The school day begins promptly at 7:00am (with breakfast served until 7:20) and ends at 2:10pm every day. -

May 10, 2016 the Honorable John B. King, Jr. Secretary of Education 400

May 10, 2016 The Honorable John B. King, Jr. Secretary of Education 400 Maryland Avenue, SW Washington, DC 20202 Dear Secretary King: As teachers and principals in Title I schools, we are writing to urge you to ensure that one of the most important provisions of the Every Student Succeeds Act – the provision that ensures that federal Title I funds are supplemental to state and local school funding – is fully and fairly enforced by states. This provision goes to the heart of this civil rights law because it is intended to ensure that federal resources are spent to provide the additional educational resources that students need to succeed. While leaders in Congress agree that ensuring equity for all students is a core component of the new law, the steps to honor this intent and carry it out are complex, controversial, and could have unintended consequences. Making smart, fair choices as the law is implemented will take concerted effort by everyone involved. The purpose of Title I is to “provide all children significant opportunity to receive a fair, equitable, and high-quality education, and to close educational achievement gaps.” As teachers and principals in Title I schools who are working every day to close these achievement gaps, we see first-hand the importance to our students of the critical services and resources made available through supplemental Title I funding. If this important ESSA provision is not properly enforced, we are concerned that some states could misunderstand the law's intent and use Title I for other purposes, including using it to replace state and local funding. -

2019-2020 Community Health Implementation Plan

2019-2020 COMMUNITY HEALTH IMPLEMENTATION PLAN MGH Community Health Implementation Plan Executive Summary Introduction A Community Health Implementation Plan (CHIP) is a road map to address community-identified public health challenges identified through the Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA), (www.massgeneral.org/cchi/), both conducted triennially. This report is the 2019-2022 CHIP for Massachusetts General Hospital. The Mass General 2019 CHNA and CHIP are based on our participation in two first ever collaborative processes in Boston and North Suffolk (Chelsea, Revere, and Winthrop). In each collaborative, participants engaged community organizations, local officials, schools, health care providers, the business and faith communities, residents, and others in an approximately year-long process. The process was tailored to unique local conditions, to better understand the health issues that most affect communities and the assets available to address them. Boston and North Suffolk have conducted their own CHNAs and CHIPs that can be found here: www.BostonCHNA.org and www.northsouffolkassessment.org. Hospitals are required by regulators (MA Attorney General, IRS) to produce their own CHNA and CHIP, approved by a governing board of the institution. Mass General used the Boston and North Suffolk implementation plans as guidance for its own and engaged content experts to complete the CHIP. The Priorities The guiding principle for the Boston and North Suffolk collaboratives is to achieve racial and ethnic health equity. In all communities, social determinants of health emerged as top priorities, as up to 80% of health status is determined by the social and economic conditions where we live and work. Notably, this is the first CHNA ever in which housing and economic issues rose to the top of the list. -

COMMONWEALTH of MASSACHUSETTS Division of Administrative Law Appeals Bureau of Special Education Appeals

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS Division of Administrative Law Appeals Bureau of Special Education Appeals ________________________ Jamal1 & BSEA #1606553 Holyoke Public Schools ________________________ RULING ON HOLYOKE PUBLIC SCHOOLS’ MOTION TO DISMISS This matter comes before the Hearing Officer on the Motion of the Holyoke Public Schools (hereinafter “Holyoke”) to Dismiss the Parent’s Hearing Request. The Parent opposes the Motion. At issue are tort and civil rights claims arising from the alleged abuse and neglect of the Student by teachers and staff in his special education program, as well as the alleged failure of Holyoke to properly supervise its staff and program. On February 22, 2016 the Parent filed a Request for Hearing at the BSEA alleging that her son, Jamal, had suffered significant physical and emotional harm at school due to the negligent and intentional actions of Holyoke Public School personnel. The Parent sought an Order finding that she is entitled to recover damages for the violation of Jamal’s due process rights under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, 42 U.S.C. §12131-12165, 20 U.S.C. § 1681, and M.G.L. c. 12, §11 H, for Holyoke’s negligence, and for Parent’s loss of consortium, based on Holyoke’s knowing and willing failure to take adequate steps to ensure Jamal’s safety. The matter was set for Hearing on March 24, 2016. After several postponements were granted for good cause this action was consolidated with seven other Hearing Requests involving similar circumstances and identical requests for relief. Holyoke filed a Motion to Dismiss the consolidated appeals on May 26, 2016.