Vol. 14, No. 1 March 2005 Part 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

String Quartet in E Minor, Op 83

String Quartet in E minor, op 83 A quartet in three movements for two violins, viola and cello: 1 - Allegro moderato; 2 - Piacevole (poco andante); 3 - Allegro molto. Approximate Length: 30 minutes First Performance: Date: 21 May 1919 Venue: Wigmore Hall, London Performed by: Albert Sammons, W H Reed - violins; Raymond Jeremy - viola; Felix Salmond - cello Dedicated to: The Brodsky Quartet Elgar composed two part-quartets in 1878 and a complete one in 1887 but these were set aside and/or destroyed. Years later, the violinist Adolf Brodsky had been urging Elgar to compose a string quartet since 1900 when, as leader of the Hallé Orchestra, he performed several of Elgar's works. Consequently, Elgar first set about composing a String Quartet in 1907 after enjoying a concert in Malvern by the Brodsky Quartet. However, he put it aside when he embarked with determination on his long-delayed First Symphony. It appears that the composer subsequently used themes intended for this earlier quartet in other works, including the symphony. When he eventually returned to the genre, it was to compose an entirely fresh work. It was after enjoying an evening of chamber music in London with Billy Reed’s quartet, just before entering hospital for a tonsillitis operation, that Elgar decided on writing the quartet, and he began it whilst convalescing, completing the first movement by the end of March 1918. He composed that first movement at his home, Severn House, in Hampstead, depressed by the war news and debilitated from his operation. By May, he could move to the peaceful surroundings of Brinkwells, the country cottage that Lady Elgar had found for them in the depth of the Sussex countryside. -

Journal September 1984

The Elgar Society JOURNAL ^■m Z 1 % 1 ?■ • 'y. W ■■ ■ '4 September 1984 Contents Page Editorial 3 News Items and Announcements 5 Articles: Further Notes on Severn House 7 Elgar and the Toronto Symphony 9 Elgar and Hardy 13 International Report 16 AGM and Malvern Dinner 18 Eigar in Rutland 20 A Vice-President’s Tribute 21 Concert Diary 22 Book Reviews 24 Record Reviews 29 Branch Reports 30 Letters 33 Subscription Detaiis 36 The editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views The cover portrait is reproduced by kind permission of National Portrait Gallery This issue of ‘The Elgar Society Journal’ is computer-typeset. The computer programs were written by a committee member, Michael Rostron, and the processing was carried out on Hutton -t- Rostron’s PDPSe computer. The font used is Newton, composed on an APS5 photo-typesetter by Systemset - a division of Microgen Ltd. ELGAR SOCIETY JOURNAL ISSN 0143-121 2 r rhe Elgar Society Journal 01-440 2651 104 CRESCENT ROAD, NEW BARNET. HERTS. EDITORIAL September 1984 .Vol.3.no.6 By the time these words appear the year 1984 will be three parts gone, and most of the musical events which took so long to plan will be pleasant memories. In the Autumn months there are still concerts and lectures to attend, but it must be admitted there is a sense of ‘winding down’. However, the joint meeting with the Delius Society in October is something to be welcomed, and we hope it may be the beginning of an association with other musical societies. -

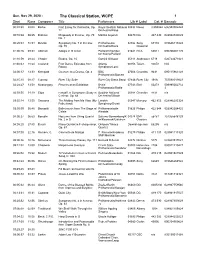

29, 2020 - the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Nov 29, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 08:08 Barber First Essay for Orchestra, Op. Royal Scottish National 08830 Naxos 8.559024 636943902424 12 Orchestra/Alsop 00:10:3808:25 Brahms Rhapsody in B minor, Op. 79 Martha Argerich 04470 DG 447 430 028944743029 No. 1 00:20:03 38:53 Dvorak Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Philharmonia 02982 Sony 67174 074646717424 Op. 70 Orchestra/Davis Classical 01:00:2609:33 Albinoni Adagio in G minor Paillard Chamber 01641 RCA 60011 090266001125 Orchestra/Paillard 01:10:59 28:44 Chopin Etudes, Op. 10 Garrick Ohlsson 05311 Arabesque 6718 026724671821 01:40:4318:24 Copland Four Dance Episodes from Atlanta 00356 Telarc 80078 N/A Rodeo Symphony/Lane 02:00:3713:33 Korngold Overture to a Drama, Op. 4 BBC 07006 Chandos 9631 095115963128 Philharmonic/Bamert 02:15:1008:17 Curnow River City Suite River City Brass Band 07846 River City 198A 753598019823 02:24:2733:58 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition Berlin 07743 EMI 00273 509995002732 Philharmonic/Rattle 3 02:59:55 34:19 Elgar Falstaff, A Symphonic Study in Scottish National 00988 Chandos 8431 n/a C minor, Op. 68 Orchestra/Gibson 03:35:1413:55 Smetana The Moldau from Ma Vlast (My London 05047 Mercury 462 953 028946295328 Fatherland) Symphony/Dorati 03:50:09 08:48 Donizetti Ballet music from The Siege of Philharmonia/de 01826 Philips 422 844 028942284425 Calais Almeida 04:00:2706:53 Borodin Nocturne from String Quartet Salerno-Sonnenberg/K 04974 EMI 56481 724355648129 No. -

Vol. 14, No. 4 March 2006

Cockaigne (In London Town) • Concert Allegro • Grania and D • May Song • Dream Children • Coronation Ode • Weary Wind West • Skizze • Offertoire • The Apostles • In The South (Ala Introduction and Allegro • EveningElgar Scene Society • In Smyrna • The Kin • Wand of Youth • How Calmly the Evening • Pleading • Go, S Mine • Elegy • Violin Concerto in B minor • Romance • Sym No.2 • O Hearken Thouournal • Coronation March • Crown of India • G the Lord • Cantique • The Music Makers • Falstaff • Carissima • S • The Birthright • The Windlass • Death on the Hills • Give Un Lord • Carillon • Polonia • Une Voix dans le Desert • The Sta Express • Le Drapeau Belge • The Spirit of England • The Frin the Fleet • The Sanguine Fan • Violin Sonata in E minor • Quartet in E minor • Piano Quintet in A minor • Cello Concer minor • King Arthur • The Wanderer • Empire March • The H Beau Brummel • Severn Suite • Soliloquy • Nursery Suite • A Organ Sonata • Mina • The Spanish Lady • Chantant • Reminisc • Harmony Music • Promenades • Evesham Andante • Ros (That's for Remembrance) • Pastourelle • Virelai • Sevillana Idylle • Griffinesque • Gavotte • Salut d'Amour • Mot d'Am Bizarrerie • O Happy Eyes • My Love Dwelt in a Northern Froissart • Spanish Serenade • La Capricieuse • Serenade • The Knight • Sursum Corda • The Snow • Fly, Singing Bird • Fro Bavarian Highlands • The Light of Life • King Olaf • Imperial M The Banner of St George • MARCHTe Deum and 2006 Benedictus Vol.14, No.4 • Caract Variations on an Original Theme (Enigma) • Sea Pictures • Ch d N it Ch d -

Vol. 13, No.2 July 2003

Chantant • Reminiscences • Harmony Music • Promenades • Evesham Andante • Rosemary (That's for Remembrance) • Pastourelle • Virelai • Sevillana • Une Idylle • Griffinesque • Ga Salut d'Amour • Mot d'AmourElgar • Bizarrerie Society • O Happy Eyes • My Dwelt in a Northern Land • Froissart • Spanish Serenade • La Capricieuse • Serenade • The Black Knight • Sursum Corda • T Snow • Fly, Singing Birdournal • From the Bavarian Highlands • The of Life • King Olaf • Imperial March • The Banner of St George Deum and Benedictus • Caractacus • Variations on an Origina Theme (Enigma) • Sea Pictures • Chanson de Nuit • Chanson Matin • Three Characteristic Pieces • The Dream of Gerontius Serenade Lyrique • Pomp and Circumstance • Cockaigne (In London Town) • Concert Allegro • Grania and Diarmid • May S Dream Children • Coronation Ode • Weary Wind of the West • • Offertoire • The Apostles • In The South (Alassio) • Introduct and Allegro • Evening Scene • In Smyrna • The Kingdom • Wan Youth • How Calmly the Evening • Pleading • Go, Song of Mine Elegy • Violin Concerto in B minor • Romance • Symphony No Hearken Thou • Coronation March • Crown of India • Great is t Lord • Cantique • The Music Makers • Falstaff • Carissima • So The Birthright • The Windlass • Death on the Hills • Give Unto Lord • Carillon • Polonia • Une Voix dans le Desert • The Starlig Express • Le Drapeau Belge • The Spirit of England • The Fring the Fleet • The Sanguine Fan • ViolinJULY Sonata 2003 Vol.13, in E minor No.2 • Strin Quartet in E minor • Piano Quintet in A minor • Cello Concerto -

The Cambridge Companion to Elgar Edited by Daniel M

Cambridge University Press 0521826233 - The Cambridge Companion to Elgar Edited by Daniel M. Grimley and Julian Rushton Index More information Index Acworth, H. A., 26, 64, 70, 72, 75, 76, 77, 78 Binge, Ronald, 77 Alexandra, Queen, 28, 30, 60 Binyon, Laurence, 83, 138, 173, 203, 219–20 Allen, Sir Hugh, 23 Winnowing Fan, The, 219 Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung, 204, 205–6, 211 Birmingham, 6, 8, 17, 18, 20, 52, 82, 87, 90, 95, Anderson, Robert, 1, 86, 101, 223 113, 140, 147, 204 Argyll, 9th Duke of, see Campbell, John Birmingham and Midland Institute, 22 Douglas Sutherland Birmingham Festival, 18, 20, 94, 100, Armes, Philip, 17 101 Arnold, Matthew, 61 Birmingham Oratory, 91 Ashton, Sir Frederick, 56, 57 Birmingham Popular Concerts, 17 Asquith, Herbert Henry, 176 Peyton Chair, University, see Elgar, Sir AssociatedBoardoftheRoyalSchoolsof Edward William Music, 12 Birmingham Daily Post, 220 Atkins, Sir Ivor, 17, 95, 104, 113, 118, Bizet, Georges, 4 186 Carmen, 140 Augustine, St Jeux d’enfants,65 Civitas Dei, 104 Blackwood, Algernon, 134, 178, 182 A Prisoner in Fairyland, 134, 178 Bach, Carl Philip Emmanuel, 4 Blair, Hugh, 17, 113, 115 Bach, Johann Sebastian, 27, 118, 193–4 Blake, Carice Elgar, 7, 25, 32, 57, 58, 82, Bach Gesellschaft, 28 188 Brandenburg Concerto No. 3, 27, 123 Bliss, Sir Arthur, 22 St Matthew Passion, 100 Boosey & Co., publisher, 28, 30, 68, Baker, Sir Herbert, 172 217 Bantock, Sir Granville, 21–2, 23 Boosey and Hawkes, publisher, 30, 43 Dante and Beatrice,22 Boughton, Edgar, 22 Russian Scenes,22 Boult, Sir Adrian, 101, 102, 191, 197, 201, Barbirolli, Sir John, 1, 129, 191, 192 202 Barrie, Sir James M., 60 Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra, 22 Peter Pan, 58, 178 Brahms, Johannes, 4, 89, 120, 141, 148, 205; Bartok,´ Bela,´ 192 developing variation, 129; influence String Quartet No. -

Elgar Organ Works

THE DOBSON ORGAN OF MERTON COLLEGE, OXFORD Elgar BENJAMIN NICHOLAS Organ wor ks EDWARD ELGAR (1857–1934): ORGAN WORKS THE DOBSON ORGAN OF MERTON COLLEGE, OXFORD Sonata for Organ in G major, Op. 28 Benjamin Nicholas 1 I. Allegro maestoso [9:03] 2 II. Allegretto [4:37] 3 III. Andante espressivo [6:31] 4 IV. Presto (comodo) [7:05] 5 ‘Nimrod’ from ‘Enigma’ Variations, Op. 36 [3:56] transcr. by W. H. Harris 6 Prelude to The Kingdom, Op. 51 [9:43] transcr. by A. Herbert Brewer* 7 Gavotte [5:50] transcr. by Edwin H. Lemare Vesper Voluntaries, Op. 14 8 Introduction: Adagio – [1:33] 9 I. Andante [1:20] 10 II. Allegro [2:57] 11 III. Andantino [2:42] 12 IV. Allegretto piacevole [1:56] 13 Intermezzo [0:44] 14 V. Poco lento [2:03] 15 VI. Moderato [1:57] 16 VII. Allegretto pensoso [2:00] 17 VIII. Poco allegro – Coda [4:27] Recorded on 25-26 June 2015 in Cover design: John Christ Join the Delphian mailing list: the Chapel of Merton College, Oxford Booklet design: Drew Padrutt www.delphianrecords.co.uk/join Total playing time [68:33] Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter Benjamin Nicholas photo: John Cairns 24-bit digital editing: Adam Binks Booklet editor: John Fallas Like us on Facebook: 24-bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter Delphian Records Ltd – Edinburgh – UK www.facebook.com/delphianrecords *premiere recording of this arrangement Cover & booklet photography © Dobson www.delphianrecords.co.uk Pipe Organ Builders Ltd Follow us on Twitter: @delphianrecords With thanks to the Warden and Fellows of the House of Scholars of Merton College, Oxford Notes on the music The first recording of Merton’s new organ – post of Organist and Choirmaster in his own offering music and seeking commissions with attractively individual, quirky charm. -

View Program Notes

23 Season 2019-2020 Thursday, February 27, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, February 28, at 2:00 Saturday, February 29, at 8:00 Edward Gardner Conductor Paul Jacobs Organ Britten Sinfonia da Requiem, Op. 20 I. Lacrymosa— II. Dies irae— III. Requiem aeternam Daugherty Once Upon a Castle, symphonie concertante for organ and orchestra I. The Winding Road to San Simeon II. Neptune Pool III. Rosebud IV. Xanadu First Philadelphia Orchestra performances Intermission Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 Elgar Variations on an Original Theme, Op. 36 (“Enigma”) Enigma (Theme): Andante I. C.A.E. II. H.D.S.-P. III. R.B.T. IV. W.M.B. V. R.P.A. VI. Ysobel VII. Troyte VIII. W.N. IX. Nimrod X. Dorabella: Intermezzo XI. G.R.S. XII. B.G.N. XIII. ***: Romanza XIV. E.D.U.: Finale This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. These concerts are part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. Please join us following the February 27 and 29 concerts for a free Organ Postlude featuring Peter Richard Conte. Elgar from Organ Sonata in G major, Op. 28: I. Allegro maestoso Britten Prelude and Fugue on a Theme of Vittoria Elgar/arr. Conte Sospiri, Op. 70 Elgar/arr. Conte Empire March 25 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra community centers, the Mann Through concerts, tours, is one of the world’s Center to Penn’s Landing, residencies, and recordings, preeminent orchestras. -

Vol. 14, No. 5 July 2006

Cockaigne (In London Town) • Concert Allegro • Grania and Diarmid • May Song • Dream Children • Coronation Ode • Weary Wind of the West • Skizze • Offertoire • The Apostles • In The South (Alassio) • Introduction and Allegro • Evening Scene • In Smyrna • The Kingdom • Wand of Youth • How Calmly the Evening • Pleading • Go, Song of Mine • Elegy • Violin Concerto in BElgar minor •Society Romance • Symphony No.2 • O Hearken Thou • Coronation March • Crown of India • Great is ournalthe Lord • Cantique • The Music Makers • Falstaff • Carissima • Sospiri • The Birthright • The Windlass • Death on the Hills • Give Unto the Lord • Carillon • Polonia • Une Voix dans le Desert • The Starlight Express • Le Drapeau Belge • The Spirit of England • The Fringes of the Fleet • The Sanguine Fan • Violin Sonata in E minor • String Quartet in E minor • Piano Quintet in A minor • Cello Concerto in E minor • King Arthur • The Wanderer • Empire March • The Herald • Beau Brummel • Severn Suite • Soliloquy • Nursery Suite • Adieu • Organ Sonata • Mina • The Spanish Lady • Chantant • Reminiscences • Harmony Music • Promenades • Evesham Andante • Rosemary (That's for Remembrance) • Pastourelle • Virelai • Sevillana • Une Idylle • Griffinesque • Gavotte • Salut d'Amour • Mot d'Amour • Bizarrerie • O Happy Eyes • My Love Dwelt in a Northern Land • Froissart • Spanish Serenade • La Capricieuse • Serenade • The Black Knight • Sursum Corda • The Snow • Fly, SingingJULY Bird 2006 • FromVol. 14, No.the 5 Bavarian Highlands • The Light of Life • King Olaf • Imperial March • The Banner of St George • Te Deum and Benedictus • Caractacus • Variations on an Original Theme (Enigma) • The Elgar Society The Elgar Society Journal Founded 1951 362 Leymoor Road, Golcar, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire HD7 4QF Telephone & Fax: 01484 649108 Email: [email protected] President Richard Hickox, CBE July 2006 Vol. -

Vol. 15, No. 3 November 2007

Cockaigne (In London Town) • Concert Allegro • Grania and Diarmid • May Song • Dream Children • Coronation Ode • Weary Wind of the West • Skizze • Offertoire • The Apostles • In The South (Alassio) • Introduction and Allegro • Evening Scene • In Smyrna • The Kingdom • Wand of Youth • HowElgar Calmly Society the Evening • Pleading • Go, Song of Mine • Elegy • Violin Concerto in B minor • Romance • Symphony No.2 •ournal O Hearken Thou • Coronation March • Crown of India • Great is the Lord • Cantique • The Music Makers • Falstaff • Carissima • Sospiri • The Birthright • The Windlass • Death on the Hills • Give Unto the Lord • Carillon • Polonia • Une Voix dans le Desert • The Starlight Express • Le Drapeau Belge • The Spirit of England • The Fringes of the Fleet • The Sanguine Fan • Violin Sonata in E minor • String Quartet in E minor • Piano Quintet in A minor • Cello Concerto in E minor • King Arthur • The Wanderer • Empire March • The Herald • Beau Brummel • Severn Suite • Soliloquy • Nursery Suite • Adieu • Organ Sonata • Mina • The Spanish Lady • Chantant • Reminiscences • Harmony Music • Promenades • Evesham Andante • Rosemary (That's for Remembrance) • Pastourelle • Virelai • Sevillana • Une Idylle • Griffinesque • Gavotte • Salut d'Amour • Mot d'Amour • Bizarrerie • O Happy Eyes • My Love Dwelt in a Northern Land • Froissart • Spanish Serenade • La Capricieuse • Serenade • The Black Knight • Sursum Corda • The Snow • Fly, Singing Bird • From the Bavarian Highlands • The Light of LifeNOVEMBER • King Olaf2007 Vol.• Imperial 15, No. -

Vol.11 No.2 July 1999

The Elgar Society JOURNAL JULY 1999 Vol.11 No.2 ELGAR’S TE DEUM & BENEDICTUS John Winter [Dr Winter is Senior Lecturer at Trinity College of Music, London. He is a general freelance musician, and holds a PhD from the University of East Anglia on contemporary church music.] There is arguably no better way to understand a piece of music than to rehearse it thoroughly before performing it. When this rehearsal involves work with an amateur choir the learning process is even greater. This has recently been my experience with Elgar’s Te Deum and Benedictus, and Give unto the Lord, working with a non-auditioned, all-ability choir, teaching virtually every note and explaining every subtlety of rubato. My appreciation of these works’ structure is all the greater for this preparation. Elgar’s liturgical music rarely gets a good press. There is barely a reference, and that a derogatory one, in New Grove. At best it gets mentioned in passing; at worst it is derided under the label of Victorian triumphalism. Worst of all, apart from Ave verum corpus, it is rarely performed. The Te Deum and Benedictus in F, Op 34, dates from 1897, and thus comes not only at the climax of Elgar’s ‘formative’ period, but also at the height of his ‘imperialist’ style. Op 32 was the Imperial March, his first major commission for a London audience, to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. Op 33 was The Banner of St George, and Op 35, Caractacus. John Allison’s book, Edward Elgar : Sacred Music,1 is exceptional in giving due consideration to the lesser-known works and incomplete fragments, along with valuable background to this particular work. -

Justin Solomon 1 Deconstructing the Definitive Recording: Elgar's Cello Concerto and the Influence of Jacqueline Du Pré Accou

Justin Solomon 1 Deconstructing the Definitive Recording: Elgar’s Cello Concerto and the Influence of Jacqueline du Pré Accounts of Jacqueline du Pré’s 1965 recording session for the Elgar Cello Concerto with Sir John Barbirolli border on mythical. Only twenty years old at the time, du Pré impressed the audio engineers and symphony members so much that word of a historic performance quickly spread to an audience of local music enthusiasts, who arrived after a break to witness the remainder of the session.1 Reviewers of the recording uniformly praised the passion and depth of du Pré’s interpretation; one reviewer went so far as to dub the disc “the standard version of the concerto, with or without critical acclaim.”2 Even du Pré seemed to sense that the recording session would become legendary. Despite the fact that the final recording was produced from thirty-seven takes spanning the entirety of the Concerto, du Pré hinted to her friends that “she had played the concerto straight through,” as if the recording were the result of a single inspired performance rather than a less glamorous day of false starts and retakes.3 Without doubt, du Pré’s recording is one of the most respected interpretations of the Concerto. Presumably because of the effectiveness of the recording and the attention it received, the famous cellist Mstislav Rostropovich “erased the concerto from his repertory” after the recording was released.4 For this reason, it comes as no surprise that in the wake of such a respected and widely distributed rendition, amateur and professional cellists alike would be conscious of du Pré’s stylistic choices and perhaps imitate their most attractive features.