Road Show (Review)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAMILLE A. BROWN Choreographer, Performer, Teacher, Cultural Innovator

CAMILLE A. BROWN Choreographer, Performer, Teacher, Cultural Innovator FOUNDER/ARTISTIC DIRECTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER/PERFORMER 2006-present Camille A. Brown & Dancers, contemporary dance company based in New York City www.camilleabrown.org FILM/TELEVISION Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom George C. Wolfe Netflix Jesus Christ Superstar Live David Leveaux NBC BROADWAY Disney’s Aida (Fall 2020) Schele Williams Broadway Theatre TBD Soul Train (2021-22) Kamilah Forbes Broadway Theatre TBD Basquiat (TBD) John Doyle Broadway Theatre TBD Pal Joey (TBD) Tony Goldwyn Broadway Theatre TBD Choir Boy Trip Cullman Samuel Friedman Theatre (MTC) *nominee Tony, Drama Desk Awards Once on This Island Michael Arden Circle in the Square Theatre *nominee Chita Rivera, Outer Critics Circle, Drama Desk Awards A Streetcar Named Desire Emily Mann Broadhurst Theatre OFF-BROADWAY/NEW YORK The Suffragists (October 2020) Leigh Silverman The Public Theater Thoroughly Modern Millie Lear DeBessonet Encores! City Center For Colored Girls Leah Gardiner The Public Theater Porgy and Bess James Robinson The Metropolitan Opera Much Ado About Nothing Kenny Leon Shakespeare in the Park *winner: Audelco Award 2019 Toni Stone Pam McKinnon Roundabout Theatre Company This Ain’t Not Disco Darko Trensjak Atlantic Theatre Company Bella: An American Tall Tale Robert O’Hara Playwrights HoriZons *winner: Lucille Lortel Award 2017 Cabin in the Sky Ruben Santiago-Hudson New York City Center (Encores!) Fortress of Solitude Daniel Aukin The Public Theater *nominee Lucille Lortel Award tick, tick…BOOM! Oliver Butler New York City Center (Encores!) The Box: A Black Comedy Seth Bockley The Irondale Soul Doctor Danny Wise New York Theatre Workshop 450 West 24th Street Suite 1C New York New York 10011 (212) 221-0400 Main (212) 881-9492 Fax www.michaelmooreagency.com Department of Consumer Affairs License #2001545-DCA REGIONAL Treemonisha (May 2022) Camille A. -

“Kiss Today Goodbye, and Point Me Toward Tomorrow”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By BRYAN M. VANDEVENDER Dr. Cheryl Black, Dissertation Supervisor July 2014 © Copyright by Bryan M. Vandevender 2014 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 Presented by Bryan M. Vandevender A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Cheryl Black Dr. David Crespy Dr. Suzanne Burgoyne Dr. Judith Sebesta ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I incurred several debts while working to complete my doctoral program and this dissertation. I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to several individuals who helped me along the way. In addition to serving as my dissertation advisor, Dr. Cheryl Black has been a selfless mentor to me for five years. I am deeply grateful to have been her student and collaborator. Dr. Judith Sebesta nurtured my interest in musical theatre scholarship in the early days of my doctoral program and continued to encourage my work from far away Texas. Her graduate course in American Musical Theatre History sparked the idea for this project, and our many conversations over the past six years helped it to take shape. -

Sondheim's 'Assassins' Playwrights Horizons Through Feb

THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER, MONDAY. JANUARY 28, 1991 49 Theater review Sondheim's 'Assassins' Playwrights Horizons Through Feb. 16 ASSASSINS Director Jerry Zaks by ROBERT OSBORNE Music-lyrics Stephen Sondheim NEW YORK — Stephen Sond- Book John Weidman heim's latest musical, "Assassins," is a Set design Loren Sherman Costume design William Ivey Long raging disappointment. Offbeat, it is. Lighting Paul Gallo Controversial, it is. Daring, it is. Good, Musical director Paul Gemignani it isn't. Irresponsible, it may be. Choreography D. J. Giagni Cast: Victor Garber, Patrick Cassidy, Terrence There's every possibility this Mann, Jonathan Hadary, Greg Germano, Eddie Sondheimer will be snuffed out Korbich, Lee Wiling'. Annie Golden. Debra Monk, quickly, despite the fact there's not a Jam Alexander. Joy Franz, Lyn Greene, John Jelli- son, Marco Olson, William Parry, Michael Shul- seat to be had during its limited man tryout run at this 139-seat off- Broadway house. Except for diehard of the song that opens and closes the Sondheim fans who'll want a gander show, "Everybody's Got the Right at anything done by the composer- (to a Dream)." lyricist, there's little here that will While a troubador-narrator (ex- satisfy or attract most theatergoers. cellently done by Patrick Cassidy) The show is a 90-minute musical counters with the suggestion "Guns kalediscope focusing on nine notori- don't right the wrongs, and soon the ous figues of history who either country's back where it belongs," killed, or attempted to kill, U.S. more emphasis is given to the theory presidents from Lincoln to Reagan. -

Guest Artists

Guest Artists George Hamilton, Broadway and Film Actor, Broadway Actresses Charlotte D’Amboise & Jasmine Guy speaks at a Chicago Day on Broadway speak at a Chicago Day on Broadway Fashion Designer, Tommy Hilfiger, speaks at a Career Day on Broadway SAMPLE BROADWAY GUEST ARTISTS CHRISTOPHER JACKSON - HAMILTON Christopher Jackson- Hamilton – original Off Broadway and Broadway Company, Tony Award nomination; In the Heights - original Co. B'way: Orig. Co. and Simba in Disney's The Lion King. Regional: Comfortable Shoes, Beggar's Holiday. TV credits: "White Collar," "Nurse Jackie," "Gossip Girl," "Fringe," "Oz." Co-music director for the hit PBS Show "The Electric Company" ('08-'09.) Has written songs for will.i.am, Sean Kingston, LL Cool J, Mario and many others. Currently writing and composing for "Sesame Street." Solo album - In The Name of LOVE. SHELBY FINNIE – THE PROM Broadway debut! “Jesus Christ Superstar Live in Concert” (NBC), Radio City Christmas Spectacular (Rockette), The Prom (Alliance Theatre), Sarasota Ballet. Endless thanks to Casey, Casey, John, Meg, Mary-Mitchell, Bethany, LDC and Mom! NICKY VENDITTI – WICKED Dance Captain, Swing, Chistery U/S. After years of practice as a child melting like the Wicked Witch, Nicky is thrilled to be making his Broadway debut in Wicked. Off-Broadway: Trip of Love (Asst. Choreographer). Tours: Wicked, A Chorus Line (Paul), Contact, Swing! Love to my beautiful family and friends. BRITTANY NICHOLAS – MEAN GIRLS Brittany Nicholas is thrilled to be part of Mean Girls. Broadway: Billy Elliot (Swing). International: Billy Elliot Toronto (Swing/ Dance Captain). Tours: Billy Elliot First National (Original Cast), Matilda (Swing/Children’s Dance Captain). -

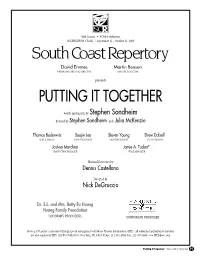

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

Hould Ward Final Document 2013 Resume

ANNANN HOULDHOULD--WARDWARD designer Broadway PUMPBOYS AND DINETTES (postponed spring 2012) John Doyle, dir. PEOPLE IN THE PICTURE Leonard Foglia, dir. FREEMAN OF COLOR George C. Wolfe, dir. 2011 Drama Desk Nomination A CATERED AFFAIR John Doyle, dir. 2008 Drama Desk Nomination COMPANY John Doyle, dir. DANCE OF THE VAMPIRES John Rando, dir. MORE TO LOVE Jack O'Brien, dir. LITTLE ME Rob Marshall, dir. DREAM Wayne Cilento, dir. ON THE WATERFRONT Adrian Hall, dir. THE MOLIERE COMEDIES Michael Langham, dir. BEAUTY AND THE BEAST Rob Roth, dir. 1994 Tony Award 1994 American Theater Wing Design Award 1994 Outer Critics Circle Award Nomination TIMON OF ATHENS Michael Langham, dir. IN THE SUMMER HOUSE Joanne Akalaitis, dir. 1994 American Theater Wing Design Nomination 3 MEN ON A HORSE John Tillinger, dir. ST. JOAN Michael Langham, dir. FALSETTOS James Lapine, dir. INTO THE WOODS James Lapine, dir. 1989 Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award 1988 Tony Nomination 1988 Outer Critics Circle Nomination 1988 Drama Desk Nomination HARRIGAN N’ HART Joe Layton, dir. 1985 Maharam Award Nomination SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE James Lapine, dir. 1984 Tony Nomination 1984 Drama Desk Nomination 1984 Maharam Award Winner Coutier Design EARTHA KITT Concert Gowns BRIAN BOITANO Skating Competition Costume, Skate America Hould-Ward Design, Film Center Building, 630 9th Ave., Ste. 1205, New York, NY 10036 e-mail: [email protected] phone: (212) 262-7480 Delacourte – Public Theater – Central Park MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR Dan Sullivan, dir MIDSUMMER NIGHTS DREAM Dan Sullivan, dir. HAMLET Oskar Eustus, dir. OPERA KING ROGER (Mariusz Kwiecien) Santa Fe Opera 2012 Stephen Wadsworth,dir PETER GRIMES (Anthony Dean Griffey) Metropolitian Opera 2008 John Doyle, dir. -

![Florence Klotz Costume Designs [Finding Aid]. Music Division, Library](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9291/florence-klotz-costume-designs-finding-aid-music-division-library-799291.webp)

Florence Klotz Costume Designs [Finding Aid]. Music Division, Library

Florence Klotz Costume Designs Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2018 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Catalog Record: https://lccn.loc.gov/2015667105 Additional search options available at: https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu018005 Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Music Division, 2018 Revised 2018 April Collection Summary Title: Florence Klotz Costume Designs Span Dates: 1971-1985 Call No.: ML31.K606 Creator: Klotz, Florence Extent: 670 items Extent: 19 containers Extent: 11.5 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. LC Catalog record: https://lccn.loc.gov/2015667105 Summary: Florence Klotz was an American costume designer best known for her work on Broadway musical collaborations with composer Stephen Sondheim and director Harold (Hal) Prince, including Follies (1971), A Little Night Music (1973), and Pacific Overtures (1976). The collection contains finished costume designs, sketches, fabric samples, and other materials for five musicals and one film adaptation. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the LC Catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically. People Coleman, Cy. On the Twentieth Century. Grossman, Larry. Grind. Klotz, Florence. Sondheim, Stephen. Follies. Sondheim, Stephen. Little night music. Sondheim, Stephen. Pacific overtures. Subjects Costume design. Costume designers. Musical theater--United States. Theater--United States. -

MACBETH Classic Stage Company JOHN DOYLE, Artistic Director TONI MARIE DAVIS, Chief Operating Officer/GM Presents MACBETH by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

MACBETH Classic Stage Company JOHN DOYLE, Artistic Director TONI MARIE DAVIS, Chief Operating Officer/GM presents MACBETH BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE WITH BARZIN AKHAVAN, RAFFI BARSOUMIAN, NADIA BOWERS, N’JAMEH CAMARA, ERIK LOCHTEFELD, MARY BETH PEIL, COREY STOLL, BARBARA WALSH, ANTONIO MICHAEL WOODARD COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN ANN HOULD-WARD SOLOMON WEISBARD MATT STINE FIGHT DIRECTOR PROPS SUPERVISOR THOMAS SCHALL ALEXANDER WYLIE ASSOCIATE ASSOCIATE ASSOCIATE SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN SOUND DESIGN DAVID L. ARSENAULT AMY PRICE AJ SURASKY-YSASI PRESS PRODUCTION CASTING REPRESENTATIVES STAGE MANAGER TELSEY + COMPANY BLAKE ZIDELL AND BERNITA ROBINSON KARYN CASL, CSA ASSOCIATES ASSISTANT DESTINY LILLY STAGE MANAGER JESSICA FLEISCHMAN DIRECTED AND DESIGNED BY JOHN DOYLE MACBETH (in alphabetical order) Macduff, Captain ............................................................................ BARZIN AKHAVAN Malcolm ......................................................................................... RAFFI BARSOUMIAN Lady Macbeth ....................................................................................... NADIA BOWERS Lady Macduff, Gentlewoman ................................................... N’JAMEH CAMARA Banquo, Old Siward ......................................................................ERIK LOCHTEFELD Duncan, Old Woman .........................................................................MARY BETH PEIL Macbeth..................................................................................................... -

Advance Program Notes Broadway in Blacksburg the Color Purple Thursday, February 13, 2020, 7:30 PM

Advance Program Notes Broadway in Blacksburg The Color Purple Thursday, February 13, 2020, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. TROIKA ENTERTAINMENT, LLC presents BOOK BY MUSIC AND LYRICS BY MARSHA NORMAN BRENDA RUSSELL ALLEE WILLIS STEPHEN BRAY BASED ON THE NOVEL WRITTEN BY ALICE WALKER AND THE WARNER BROS./AMBLIN ENTERTAINMENT MOTION PICTURE WITH MARIAH LYTTLE SANDIE LEE CHÉDRA ARIELLE ANDREW MALONE BRANDON A. WRIGHT NASHKA DESROSIERS ELIZABETH ADABALE JARRETT ANTHONY BENNETT DAVID HOLBERT PARRIS LEWIS JENAY NAIMA MON’QUEZ DEON PIPPINS GABRIELLA RODRIGUEZ SHELBY A. SYKES RENEE TITUS IVAN THOMPSON CARTREZE TUCKER JEREMY WHATLEY GERARD M. WILLIAMS SET DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN HAIR DESIGN JOHN DOYLE ANN HOULD-WARD JANE COX DAN MOSES SCHREIER CHARLES G. LAPOINTE CASTING ASSOCIATE COSTUME DESIGN BINDER CASTING CHRISTOPHER VERGARA CHAD ERIC MURNANE, C.S.A. MUSIC SUPERVISION MUSIC DIRECTOR/CONDUCTOR ORCHESTRATIONS MUSIC COORDINATION DARRYL ARCHIBALD JONATHAN GORST JOSEPH JOUBERT TALITHA FEHR EXCLUSIVE TOUR DIRECTION MARKETING & PUBLICITY DIRECTION PROJECTION SUPERVISOR COMPANY MANAGER THE BOOKING GROUP BOND THEATRICAL GROUP B.J. BELLARD BARRY BRANFORD GENERAL MANAGEMENT PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT EXECUTIVE PRODUCER BRIAN SCHRADER HEATHER CHOCKLEY KORI PRIOR ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR SAMANTHA SALTZMAN DIRECTION AND MUSICAL STAGING JOHN DOYLE The Color Purple was produced on Broadway at the Broadway Theater by Oprah Winfrey, Scott Sanders, Roy Furman, and Quincy Jones. The world premiere of The Color Purple was produced by the Alliance Theatre, Atlanta, Georgia. -

Education Resource Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine

Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine INTO THE WOODS Education Resource Music INTO THE WOODS - MUSIC RESOURCE INTRODUCTION From the creators of Sunday in the Park with George comes Into the Woods, a darkly enchanting story about life after the ‘happily ever after’. Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine reimagine the magical world of fairy tales as the classic stories of Jack and the Beanstalk, Cinderella, Little Red Ridinghood and Rapunzel collide with the lives of a childless baker and his wife. A brand new production of an unforgettable Tony award-winning musical. Into the Woods | Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine. 19 – 26 July 2014 | Arts Centre Melbourne, Playhouse Music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by James Lapine Originally Directed on Broadway by James Lapine By arrangement with Hal Leonard Australia Pty Ltd Exclusive agent for Music Theatre International (NY) 2 hours and 50 minutes including one interval. Victorian Opera 2014 – Into the Woods Music Resource 1 BACKGROUND Broadway Musical Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book and Direction by James Lapine Orchestration: Jonathan Tunick Opened in San Diego on the 4th of December 1986 and premiered in Broadway on the 5th of November, 1987 Won 3 Tony Awards in 1988 Drama Desk for Best Musical Laurence Olivier Award for Best Revival Figure 1: Stephen Sondheim Performances Into the Woods has been produced several times including revivals, outdoor performances in parks, a junior version, and has been adapted for a Walt Disney film which will be released at the end of 2014. Stephen Sondheim (1930) Stephen Joshua Sondheim is one of the greatest composers and lyricists in American Theatre. -

AS YOU LIKE IT, the First Production of Our 50Th Anniversary Season, and the First Show in Our Shakespearean Act

Welcome It is my pleasure to welcome you to AS YOU LIKE IT, the first production of our 50th anniversary season, and the first show in our Shakespearean act. Shakespeare’s plays have been a cornerstone of our work at CSC, and his writing continues to reflect and refract our triumphs and trials as individuals and collectively as a society. We inevitability turn to Shakespeare to express our despair, bewilderment, and delight. So, what better place to start our anniversary year than with the contemplative search for self and belonging in As You Like It. At the heart of this beautiful play is a speech that so perfectly encapsulates our mortality. All the world’s a stage, and we go through so many changes as we make our exits and our entrances. You will have noticed many changes for CSC. We have a new look, new membership opportunities, and are programming in a new way with more productions and a season that splits into what we have called “acts.” Each act focuses either on a playwright or on an era of work. It seemed appropriate to inaugurate this with a mini-season of Shakespeare, which continues with Fiasco Theater's TWELFTH NIGHT. Then there is Act II: Americans dedicated to work by American playwrights Terrence McNally (FIRE AND AIR) and Tennessee Williams (SUMMER AND SMOKE); very little of our repertoire has focused on classics written by Americans. This act also premieres a new play by Terrence McNally, as I feel that the word classic can also encapsulate the “bigger idea” and need not always be the work of a writer from the past. -

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding Aid Prepared by Lisa Deboer, Lisa Castrogiovanni

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding aid prepared by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier and revised by Diana Bowers-Smith. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 04, 2019 Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection , 2006; revised 2008 and 2018. 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 7 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................8 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Highlights.....................................................................................................................................9 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................10 Related Materials .....................................................................................................................................