A Method for Evaluating the Impact Wear Behavior of Multilayer Tin/Ti Coating

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10-1 CHAPTER 10 DEFORMATION 10.1 Stress-Strain Diagrams And

EN380 Naval Materials Science and Engineering Course Notes, U.S. Naval Academy CHAPTER 10 DEFORMATION 10.1 Stress-Strain Diagrams and Material Behavior 10.2 Material Characteristics 10.3 Elastic-Plastic Response of Metals 10.4 True stress and strain measures 10.5 Yielding of a Ductile Metal under a General Stress State - Mises Yield Condition. 10.6 Maximum shear stress condition 10.7 Creep Consider the bar in figure 1 subjected to a simple tension loading F. Figure 1: Bar in Tension Engineering Stress () is the quotient of load (F) and area (A). The units of stress are normally pounds per square inch (psi). = F A where: is the stress (psi) F is the force that is loading the object (lb) A is the cross sectional area of the object (in2) When stress is applied to a material, the material will deform. Elongation is defined as the difference between loaded and unloaded length ∆푙 = L - Lo where: ∆푙 is the elongation (ft) L is the loaded length of the cable (ft) Lo is the unloaded (original) length of the cable (ft) 10-1 EN380 Naval Materials Science and Engineering Course Notes, U.S. Naval Academy Strain is the concept used to compare the elongation of a material to its original, undeformed length. Strain () is the quotient of elongation (e) and original length (L0). Engineering Strain has no units but is often given the units of in/in or ft/ft. ∆푙 휀 = 퐿 where: is the strain in the cable (ft/ft) ∆푙 is the elongation (ft) Lo is the unloaded (original) length of the cable (ft) Example Find the strain in a 75 foot cable experiencing an elongation of one inch. -

Impact of Flow Velocity on Surface Particulate Fouling - Theoretical Approach

Journal of American Science 2012;8(9) http://www.jofamericanscience.org Impact of Flow velocity on Surface Particulate Fouling - Theoretical Approach Mostafa M. Awad Mech. Power Eng. Dept., Faculty of Engineering, Mansoura University, Egypt [email protected] Abstract: The objective of this research is to study the effect of flow velocity on surface fouling. A new theoretical approach showing the effect of flow velocity on the particulate fouling has been developed. This approach is based on the basic fouling deposition and removal processes. The present results show that, the flow velocity has a strong effect on both the fouling rate and the asymptotic fouling factor; where the flow velocity affects both the deposition and removal processes. Increasing flow velocity results in decreasing both of the fouling rate and asymptotic values. Comparing the obtained theoretical results with available experimental ones showed good agreement between them. The developed model can be used as a very useful tool in the design and operation of the heat transfer equipment by controlling the parameters affecting fouling processes. [Mostafa M. Awad. Impact of Flow velocity on Surface Particulate Fouling - Theoretical Approach. J Am Sci 2012;8(9):442-449]. (ISSN: 1545-1003). http://www.jofamericanscience.org. 62 Keywords: Surface fouling, flow velocity, particle sticking, mass transfer. 1. Introduction increasing the flow velocity. They also found that the Fouling of heat transfer surface is defined as the asymptotic fouling factor is very sensitive to the flow accumulation of unwanted material on the heat transfer velocity especially at low flow velocities where this surface. This accumulation deteriorates the ability of sensitivity decreases with increasing flow velocity. -

Ductile Brittle Transition

XIX. EVALUATION OF DUCTILE/BRITTLE FAILURE THEORY, DERIVATION OF THE DUCTILE/BRITTLE TRANSITION TEMPERATURE Introduction The ductile/brittle transition for failure with all of its implications and ramifications is one of the most widely observed and universally acknowledged physical effects in existence. Paradoxically though it also is one of the least understood of all the physical properties and physical effects that are encountered in the world of materials applications. Critical judgments are made on the basis of experience only, purely heuristic and intuitive. The resolution of the ductile/brittle transition into a physically meaningful and useful mathematical form has always been problematic and elusive. It often has been suggested that such a development is highly unlikely. The rigorous answer to this question remains and continues as one of the great scientific uncertainties, challenges. The long time operational status of ductile/brittle behavior has reduced to a statement of the strain at failure in uniaxial tension. If the strain at failure is large, the material is said to be ductile. If the strain at failure is small, it is brittle. Loose and uncertain though this is, it could be general, even complete, if the world were one-dimensional. But the physical world is three-dimensional and in stress space it is six or nine dimensional. Even more complicating, some of the stress components are algebraic. So the problem is large and difficult, perhaps immensely large and immensely difficult. To even begin to grapple with the ductile/brittle transition one must first have a firm grasp on a general and basic theory of failure. -

Little Book of Dynamic Buckling

. Little Book of Dynamic Buckling Herbert E. Lindberg September 2003 LCE Science/Software 1 Preface A graduate program in mechanics (often part of aero/astronautical, civil or mechanical engineering) generally includes a short series on elastic stability of structures. Within the confines of available time, focus is on stability under static loading, with dynamic loading from earthquakes, aerodynamics, impact and so on touched on only briefly except for students with thesis topics in these areas. This short book is intended as a brief introduction to dynamic buckling that can be covered in the limited time available in a broad graduate program. It is small and inexpensive enough that the student can own his or her own copy, rather than simply taking notes during lectures extracted by the teacher from the several full-size texts available on this topic, including one by the present author. The book introduces concepts of dynamic buckling in the simplest possible context for each phenomenon. The phenomena treated all fall under the definition of dynamic stability of structures under time-varying parametric loading. The goal is met by treating simple bars under axial loads, rings under lateral pulse loads, and cylindrical shells under radial and axial loads. The present document includes only a general introduction and then comprehensive presentation of theory and experimental data for bars under static and impact loads. Sections on rings and shells will be made available as orders are received. In all cases motion is precipitated by inevitable imperfections in structural shape. Sometimes these appear as a simple parameter, as in the eccentricity of impact. -

On Impact Testing of Subsize Charpy V-Notch Type Specimens*

DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsi• bility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Refer• ence herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recom• mendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. ON IMPACT TESTING OF SUBSIZE CHARPY V-NOTCH TYPE SPECIMENS* Mikhail A. Sokolov and Randy K. Nanstad Metals and Ceramics Division OAK RIDGE NATIONAL LABORATORY P.O. Box 2008 Oak Ridge, TN 37831-6151 •Research sponsored by the Office of Nuclear Regulatory Research, U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, under Interagency Agreement DOE 1886-8109-8L with the U.S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC05-84OR21400 with Lockheed Martin Energy Systems. The submitted manuscript has been authored by a contractor of the U.S. Government under contract No. DE-AC05-84OR21400. Accordingly, the U.S. Government retains a nonexclusive, royalty-free license to publish or reproduce the published form of this contribution, or allow others to do so, for U.S. Government purposes. Mikhail A. -

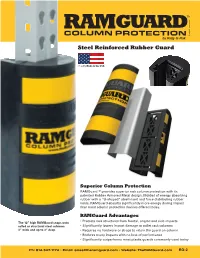

RAM Guard Column Protector

by Ridg-U-Rak Steel Reinforced Rubber Guard Superior Column Protection RAMGuard™ provides superior rack column protection with its patented Rubber Armored Metal design. Molded of energy absorbing rubber with a “U-shaped” steel insert and force distributing rubber voids, RAMGuard absorbs significantly more energy during impact than most column protection devices offered today. RAMGuard Advantages The 12” high RAMGuard snaps onto • Protects rack structures from frontal, angled and side impacts rolled or structural steel columns • Significantly lowers impact damage to pallet rack columns 3” wide and up to 3” deep. • Requires no hardware or straps to retain the guard on column • Endures many impacts with no loss of performance • Significantly outperforms most plastic guards commonly used today Ph: 814.347.1174 • Email: [email protected] • Website: TheRAMGuard.com RG-2 RAMGuard Design Maximum Impact Resistance by Design Molded of Energy There is a wide range of products designed to Absorbing Rubber help protect pallet rack columns from the everyday abuses that commonly occur in busy warehouse U-Shaped environments. These products include steel Steel Insert reinforced columns, slant-back or offset frames, floor-mounted steel guards, bumpers, barriers and after market attachable guards. Each of these serves a purpose for different applications. Aftermarket attachable guards have a variety of applications ranging from small plants with high traffic areas to large facilities where it is critical to reduce the time and cost of replacing damaged uprights… and everything in between. There are many types, kinds and sizes of guards on the market today, but none like the RAMGuard. After nearly two years of development, testing and proto-type designs, the new patented RAMGuard delivers the greatest impact resistance available in aftermarket snap-on or strap-on column guards. -

Addressing Stress Corrosion Cracking in Turbomachinery Industry.Indd

Addressing Stress Corrosion Cracking in the Turbomachinery Industry Stress Corrosion Cracking is a common problem affecting turbomachinery components such as rotor discs, steam turbine blades and compressor impellers, and is a major factor driving component repair. This type of cracking may lead to catastrophic failures which result in unplanned down time and expensive repairs. A comprehensive root cause failure analysis is always needed to determine and confirm the root causes. Based on the findings of the analysis, different methods can be used to alleviate the cause of stress corrosion cracking. The design of the component, operating environment and other factors should be considered when selecting a method to mitigate stress corrosion cracking. Introduction Stress corrosion cracking (SCC) is a failure that occurs in a Figure 1 shows an SEM image of a fracture surface exhibiting part when the following conditions are met: intergranular mode of propagation on an integral disk of a steam turbine rotor. 1. An alloy is susceptible to stress corrosion cracking 2. Corrosive environment Care should be exercised when attributing an intergranular 3. Sufficient level of stress mode of propagation to SCC since there are other failure mechanisms (such as creep) that lead to an intergranular At Sulzer we have analyzed multiple cases of stress corrosion mode of failure. cracking on turbomachinery parts such as steam turbine rotors, steam turbine blades, shroud bands and compressor Branching of a crack is another common characteristic of impellers. SCC and optical metallography through a fracture/crack will help identify this feature. Both modes of propagation Sometimes we work with equipment where failures have can exhibit crack branching. -

Evaluation of Ductile/Brittle Failure Theory and Derivation of the Ductile/Brittle Richard M

Evaluation of Ductile/Brittle Failure Theory and Derivation of the Ductile/Brittle Richard M. Christensen Professor Research Emeritus Transition Temperature Aeronautics and Astronautics Department, Stanford University, A recently developed ductile/brittle theory of materials failure is evaluated. The failure Stanford, CA 94305 theory applies to all homogeneous and isotropic materials. The determination of the duc- e-mail: [email protected] tile/brittle transition is an integral and essential part of the failure theory. The evaluation process emphasizes and examines all aspects of the ductile versus the brittle nature of failure, including the ductile limit and the brittle limit of materials’ types. The failure theory is proved to be extraordinarily versatile and comprehensive. It even allows deriva- tion of the associated ductile/brittle transition temperature. This too applies to all homo- geneous and isotropic materials and not just some subclass of materials’ types. This evaluation program completes the development of the failure theory. [DOI: 10.1115/1.4032014] Keywords: ductile, brittle, ductile/brittle transition, ductile/brittle transition temperature, materials failure, failure theory Introduction There is one exception to this quite dire state of affairs and it is the case of what are commonly called very ductile metals. The The ductile/brittle transition for failure with all of its implica- flow of dislocations embodies the essence of ductility and it has tions and ramifications is one of the most widely observed and been a very active area of study for a great many years. The many universally acknowledged physical effects in existence. Paradoxi- related papers on the ductile/brittle transition in ductile metals cally, it is also one of the least understood of all the physical prop- generally examine the emission of dislocations at crack tips to see erties and physical effects that are encountered in the world of how local conditions can influence this. -

Impact of Hard Fouling on the Ship Performance of Different Ship Forms

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Impact of Hard Fouling on the Ship Performance of Different Ship Forms Andrea Farkas 1, Nastia Degiuli 1,*, Ivana Marti´c 1 and Roko Dejhalla 2 1 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Naval Architecture, University of Zagreb, Ivana Luˇci´ca5, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] (A.F.); [email protected] (I.M.) 2 Faculty of Engineering, University of Rijeka, Vukovarska ulica 58, 51000 Rijeka, Croatia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +38-516-168-269 Received: 3 September 2020; Accepted: 24 September 2020; Published: 26 September 2020 Abstract: The successful optimization of a maintenance schedule, which represents one of the most important operational measures for the reduction of fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emission, relies on accurate prediction of the impact of cleaning on the ship performance. The impact of cleaning can be considered through the impact of biofouling on ship performance, which is defined with delivered power and propeller rotation rate. In this study, the impact of hard fouling on the ship performance is investigated for three ship types, keeping in mind that ship performance can significantly vary amongst different ship types. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations are carried out for several fouling conditions by employing the roughness function for hard fouling into the wall function of CFD solver. Firstly, the verification study is performed, and the numerical uncertainty is quantified. The validation study is performed for smooth surface condition and, thereafter, the impact of hard fouling on resistance, open water and propulsion characteristics is assessed. -

1 Impact Test 1

IMPACT TEST 1 – Impact properties The impact properties of polymers are directly related to the overall toughness of the material. Toughness is defined as the ability of the polymer to absorb the applied energy. By analysing a stress-strain curve, it is possible to estimate the toughness of the material because it is directly proportional to the area under the curve. In this sense, impact energy is a measure of the toughness of the material. The higher the impact energy, the higher the toughness. Now, it is possible to define the impact resistance, the ability of the material to resist breaking under an impulsive load, or the ability to resist the fracture under stress applied at high velocity. The molecular flexibility plays an important role in determining the toughness and the brittleness of a material. For example, flexible polymers have an high-impact behaviour due to the fact that the large segments of molecules can disentangle very easily and can respond rapidly to mechanical stress while, on the contrary, in stiff polymers the molecular segments are unable to disentangle and respond so fast to mechanical stress, and the impact produces brittle failure. This part will be discussed into details in another chapter of this handbook. Impact properties of a polymer can be improved by adding a structure modifier, such as rubber or plasticizer, by changing the orientation of the molecules or by using fibrous fillers. Most polymers, when subjected to impact load, seem to fracture in a well defined way. Due to the impact load, impulse, the crack starts to propagate on the polymer surface. -

Impact and Postbuckling Analyses

ABAQUS/Explicit: Advanced Topics Lecture 8 Impact and Postbuckling Analyses Copyright 2005 ABAQUS, Inc. ABAQUS/Explicit: Advanced Topics L8.2 Overview • Impact Analysis • Geometric Imperfections for Postbuckling Analyses Copyright 2005 ABAQUS, Inc. ABAQUS/Explicit: Advanced Topics Impact Analysis Copyright 2005 ABAQUS, Inc. ABAQUS/Explicit: Advanced Topics L8.4 Impact Analysis • Overview – Why use ABAQUS/Explicit for impact? – Modeling Considerations (Example: Drop Test Simulation of a Cordless Mouse) • Initial model configuration • Elements • Materials • Constraints • Contact • Output – Other topics • Preloading • Submodeling Cordless mouse assembly • Mass scaling Copyright 2005 ABAQUS, Inc. ABAQUS/Explicit: Advanced Topics L8.5 Impact Analysis • Why use ABAQUS/Explicit for impact problems? – A number of factors contribute to this decision: • High-speed dynamic response • Severe nonlinearities usually encountered: – Large number of contact constraints changing rapidly – Possible extensive plasticity – Possible structural collapse • Relatively short duration of simulation – Typically up to about 20 milliseconds for a drop test – Typically up to about 120 milliseconds for a full vehicle crash • Relatively large size of models Copyright 2005 ABAQUS, Inc. ABAQUS/Explicit: Advanced Topics L8.6 Impact Analysis • Example: Drop Test Simulation of a Cordless Mouse • Initial model configuration – Model built in “just before impact” position V3 – Initial velocities applied to capture the effect of the drop – Changing drop height simply a case of changing initial velocity – Very simple to change drop orientation by adjusting floor position and changing initial velocity direction Mouse initial velocity Copyright 2005 ABAQUS, Inc. ABAQUS/Explicit: Advanced Topics L8.7 Impact Analysis – For drop test simulations, the floor is generally rigid. • A meshed rigid body is required for general contact. -

On the Physics of the Bone Fracture

International Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology 2017; 2(1): 1-4 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijot doi: 10.11648/j.ijot.20170201.11 Letter On the Physics of the Bone Fracture Martin G. Abrahamyan 1, 2 1Department of Physics, Yerevan State University, Yerevan, Armenia 2Department of Medical Physics, Yerevan “Haybusak” University, Yerevan, Armenia Email address: [email protected] To cite this article: Martin G. Abrahamyan. On the Physics of the Bone Fracture. International Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology . Vol. 2, No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-4. doi: 10.11648/j.ijot.20170201.11 Received : January 27, 2017; Accepted : March 1, 2017; Published : March 22, 2017 Abstract: The mechanics of the bones fracture is studied. The usefulness of simple physical consideration for studying of the bone fracture phenomenon is shown. Some quantitative estimations of potential energy of the bone elastic deformations as well as of impulsive forces for bone fracture, caused by sudden collision, by a fall, by road traffic accident etc., have been obtained. The dependences of the impulsive forces on the relative velocity of colliding bodies and of collision time have been established. Keywords: Bone Fracture, Impulsive Force, Sudden Collision mechanical properties: hardness, elasticity and durability [4-6]. 1. Introduction Dependence of stress σ (the internal force, F, per unit area Bone is the main material of the musculoskeletal device. In acting on the bone: σ = F/S, S is the area of the force action), the simplified look it is possible to consider that 2/3 masses of on longitudinal strain ε (the fractional change in the bone a compact bone tissue (0.5 of the volume) is inorganic length, ℓ: ε = ∆ℓ/ℓ, ∆ℓ is the measure of the bone deformation, material, mineral substance of a bone - a hydroxyapatite Figure 1) Ca 10 (РO4)6Са(OН) 2.