Nothing Stranger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Denim Doll NEW YORK — Oh, You Beautiful Doll, All Dressed in Denim — the Perfect Refrain for Frugal Fashion Girls Everywhere

The Inside: Top Specialty Retailers Pg. 12 EXPLORING GHURKA OPTIONS/3 THE NEW VERSUS/11 WWD WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • TheTHURSDAY Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • July 20, 2006 • $2.00 List Sportswear Denim Doll NEW YORK — Oh, you beautiful doll, all dressed in denim — the perfect refrain for frugal fashion girls everywhere. Resort is full of affordable denim in all shapes and styles. Here, Tyte’s stretch cotton jumpsuit, $17.50 at wholesale, worn with Star City’s cotton blouse, an Accessory Network belt, Juicy Couture earrings and Seychelles sandals. For more on the season’s best denim under $50, see pages 6 and 7. Postmortem on Rochas: Y DAVID YASSKY Y DAVID It Takes More Than Talent To Play Corporate Game By WWD Staff TSBYTIMOTHYPRIANO/FOR BECCA;TSBYTIMOTHYPRIANO/FOR STYLED B NEW YORK — Designers and brand owners /ARTIS must prioritize commercial, salable products over media glory. That’s among the chief lessons to be learned from Tuesday’s news that Procter & Gamble plans to shutter the Rochas fashion house despite PRIANO.COM; MAKEUP BY NAOMI MAKEUP BY PRIANO.COM; widespread acclaim for its designer, Olivier Theyskens, say observers. The move also underscores the increasing challenges for a luxury fashion label that hasn’t been able to diversify into other product categories BY DAVID MEDELYE/ARTISTSBYTIMOTHY DAVID BY successfully. In the past few seasons, Theyskens See Lessons, Page 13 EL: LISALLA/NEW MODELS; HAIR YORK PHOTO BY KYLE ERICKSEN; MOD KYLE PHOTO BY WWD.COM WWDTHURSDAY Sportswear FASHION ™ The mix-and-match game is a fashion mainstay, especially with a lineup A weekly update on consumer attitudes and behavior based 6 of terrifi c denim pieces of the affordable sort, all less than $50 wholesale. -

The Logo As Design Motif and Marketing Concept

The Logo as Design Motif and Marketing Concept: A Case Study of Handbags and Hand Luggage By Jennifer Moore A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Human Ecology: Design Studies) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN--MADISON 2013 Date of final oral examination: 4/16/12 This dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Beverly Gordon, Professor Emerita, Design Studies Virginia Terry Boyd, Professor Emerita, Design Studies Cynthia Jasper, Professor, Consumer Science Nancy Wong, Associate Professor, Consumer Science i Table of Contents Table of Contents i-v Abstract vi-vii List of Tables viii List of Illustrations ix-x Acknowledgements xi-xii Chapter 1: Introductory Material Rationale for this Study 1-9 Conceptual Framework 9-25 Rationale for the Selection of Handbags and Hand Luggage as the Case Study Subject 25-29 Significance 29 Research Questions 29-30 Working Propositions, Definitions, and Delimitations 30-35 Chapter 2: Review of Relevant Literature Handbags and Their Role in Fashionable Dress 37-40 The Ideology of Consumption: Consumers and Their Goods 40-52 The Business of Fashion 52-56 Postmodernism and Fashion 57-72 Branding and Brand Identity 72-80 ii A History of Fashion Before Mass Consumption 80-84 Chapter 3: Historical Background The Business of Fashion 85-89 The Designer and the Customer 89-97 Chapter 4: Methodology and Pilot Study Research Design Overview 98-100 Grounded Theory Approach 100-101 Content Analysis 101-109 Presentation -

Print Condition NEW YORK — Quirky Prints and Vivid Colors Were Key Runway Trends on Both Sides of the Atlantic, and J

FavoriteThe Fashions FromInside: Milan Pg. 12 COUNTERFEIT SCENT BUST/2 KOOBA’S INVESTORS/2 WWD WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • TheTHURSDAY Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • October 18, 2007 • $2.00 List Sportswear Print Condition NEW YORK — Quirky prints and vivid colors were key runway trends on both sides of the Atlantic, and J. Crew’s Jenna Lyons was smart to get in on the act. The creative director is right on target with her spring collection, which is fi lled with fl irty little numbers like this paisley-print linen frock. For more, see page 8. After Nixing Sun Bid, Kellwood Could Face Shareholder Pressure By Whitney Beckett he heat on Kellwood Co. is expected Tto intensify. Following the $1.96 billion company’s rejection Wednesday of a $543 million bid by Sun Capital Securities Group LLC, analysts and consultants said the firm now has to prove to shareholders that it can turn around its operations and boost its lagging share price — and do it fast. The St. Louis-based company said in a statement Wednesday that Sun Capital’s $21 a share bid “significantly undervalues the strength of Kellwood’s expanded portfolio of brands and the See Kellwood, Page13 PHOTO BY ROBERT MITRA ROBERT PHOTO BY 2 WWD, THURSDAY, OCTOBER 18, 2007 WWD.COM Kooba Partners With Private Equity Firm ontemporary luxury designer brand Kooba has a cessories line earlier in the year. new equity partner via Swander Pace Capital. As for the product exten- WWDTHURSDAY C Sportswear The private equity fi rm, which made an undis- sions, Held said the company closed investment in the women’s handbags, acces- started its women’s apparel line sories and apparel brand, is the majority stakehold- with leather jackets because the GENERAL er in the company. -

Newart May2020 CN Item Num PROPERTYOWNER LAST

NewArt_May2020 CN Item Num PROPERTYOWNER_LAST PROPERTYOWNER_FIRST Evidence Description 07046473 1 ballistic evidence submission:002 11030325 1 HARRIS FRANK 1 lighter, 1 string 11030325 1 1 lighter, 1 string 11054050 3.1 .22 caliber, 8 cartridges, REMOVED FROM GUN FOR GUN RETURN 11054050 3.1 .22 caliber, 8 cartridges, REMOVED FROM GUN FOR GUN RETURN 11054050 3.1 SNELLING LONNIE .22 caliber, 8 cartridges, REMOVED FROM GUN FOR GUN RETURN 11054050 3.1 WILLIAMS SYLVESTER .22 caliber, 8 cartridges, REMOVED FROM GUN FOR GUN RETURN 11056107 1 PRATT WILLIAM 1 recovered stolen license plate 3YC412 13010605 2.1 LEE CARLTON Test shots 13021042 1 SMITH JASON Missouri license plate, DG6-F6X. 13034032 1 K & M AUTO SALES 1-License plate D8538-AB, Missouri. 13039968 2 RASAS AMOSA cell phone 3 (1) set of Missouri license plates bearing sequence FK2-M6X MO 15. 1 plate recovered from rear of 13052321 HOGAN TERRELL vehicle's bumper and 1 from inside trunk of car. (1) piece of mail belonging to Terrell T. hogan 3 (1) set of Missouri license plates bearing sequence FK2-M6X MO 15. 1 plate recovered from rear of 13052321 PATERSON CORI vehicle's bumper and 1 from inside trunk of car. (1) piece of mail belonging to Terrell T. hogan 3 (1) set of Missouri license plates bearing sequence FK2-M6X MO 15. 1 plate recovered from rear of 13052321 UINKNOWN vehicle's bumper and 1 from inside trunk of car. (1) piece of mail belonging to Terrell T. hogan 14010374 1 UNKNOWN 2 Lighters 14013799 2 TOMPKINS WYDELL assorted ammo 14014233 1 Ballistics 14015141 2 Ballistics 14016324 2 THOMPSON GINA Ballistics 14024671 1 BECHDOLT DANIEL 1 Westone Hearing Aids 14024671 1 BLEVINS ROGER 1 Westone Hearing Aids 14024671 1 FARNSWORTH DANE 1 Westone Hearing Aids 4- 357 magnum rounds, 7- 20 ga rounds, 14 - 40 cal rounds inside magazine, 4- 380 cal rounds in 1 14024752 SNEED DOUGLAS magazine, 6- 22 cal rounds in magazine, 3- 22 cal rounds, 13- 38 special rounds. -

Special Market Issue

AUG 17_Cover V2_08ACC_ 7/7/17 1:10 PM Page 1 AUG/SEPT 2017 $7.50 SPECIAL MARKET WELLNESS: ISSUE HEALTH IS WEALTH ACCESSORIES VINTAGE: A TO Z WHAT’S OLD IS NEW List: TRAVEL the TAKES OFF TOP 100 Light &Airy ACCESSORIES FLOAT INTO VIEW WITH AN EDGE 08ACC_C001.pdf Aug 17_Top 100 Listing_08ACC_ 7/11/17 9:03 AM Page 57 the list: TOP 100 2017 ACCESSORIES BRANDS & PLAYERS … with Spring/Summer 2018 Trend Boards 1928 Collectibles, Ali-Khan New York, Me Too Accessories, ATHRA Khan for Men, Me Too Active (designer, social, trend Founded: 1968; Owner: Melvyn Bernie Founded: 1984; Owner, President & CEO: Amena jewelry and accessories, hair accessories, active, VP of Sales: Lisa Standen Koumi; VP Sales/Operations: Scott Turi; Director of men’s jewelry and accessories). Accessories brands, licenses and classifications: Merchandising & Design: Tracy McCreary; Contact: 212-685-2100, www.akamystique.com Proprietary brands—1928, 2028, Antiquities, Signature Designers: Joanne Joseph, Ninos DeChammo 1928, 1928 Hair, 1928 Bridal, T.R.U. Private Brands Accessories brands, licenses and classifications: program (all fashion jewelry). Licensed brand— Proprietary brands—Athra, Athra Luxe, Joey J, Downton Abbey (fashion jewelry). ALEX AND ANI Everlasting Flowers, Ninos DeChammo (private label Contact: 818-841-1928, www.1928.com Founded: 2004; Founder, CEO and Chief Creative fine, bridge and costume jewelry). Officer: Carolyn Rafaelian Contact: 201-964-9770; www.athra.com Accessories brands, licenses and classifications: ACCESSORY COLLECTIVE, Proprietary brands—Alex -

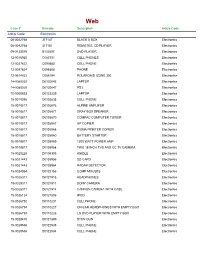

Case # Barcode Description Article Code Article Code: Electronics 06

Web Case # Barcode Description Article Code Article Code: Electronics 06-0042768 317147 BLACK X BOX Electronics 06-0042768 317151 REMOTES, CD PLAYER Electronics 09-0125076 B132807 DVD PLAYER Electronics 12-0016920 C083751 CELL PHONES Electronics 12-0027622 C099580 CELL PHONE Electronics 12-0047624 C096508 PHONE Electronics 12-0614822 C086194 POLAROAID IZONE 300 Electronics 14-0088020 D0130043 LAPTOP Electronics 14-0088020 D0130047 PS3 Electronics 15-0000653 D0122239 LAPTOP Electronics 15-0018056 D0102635 CELL PHONE Electronics 15-0018817 D0126076 ALPINE AMPLIFER Electronics 15-0018817 D0126071 GRAY BOX SPEAKER Electronics 15-0018817 D0126070 COMPAC COMPUTER TOWER Electronics 15-0018817 D0126067 HP COPIER Electronics 15-0018817 D0126066 PIXMA PRINTER COPIER Electronics 15-0018817 D0126060 BATTERY STARTER Electronics 15-0018817 D0126059 1200 WATT POWER AMP Electronics 15-0018817 D0126058 TWO 18 INCH TVS AND CC TV CAMERA Electronics 15-0020228 D0104305 KNIDLE Electronics 15-0021443 D0126956 SD CARD Electronics 15-0021443 D0126964 RADAR DETECTOR Electronics 15-0024054 D0122165 COMP MOUSES Electronics 15-0025311 D0121915 HEADPHONES Electronics 15-0025311 D0121911 SONY CAMERA Electronics 15-0025311 D0121914 CANNON CAMERA WITH CASE Electronics 15-0026124 D0121806 IPOD Electronics 15-0026732 D0110231 CELLPHONE Electronics 15-0026734 D0110227 ON-EAR HEADPHONES WITH EMPTY BOX Electronics 15-0026734 D0110226 LG DVD PLAYER WITH EMPTY BOX Electronics 15-0028410 D0121899 STUN GUN Electronics 15-0029538 D0122535 CELL PHONE Electronics 15-0029538 D0122534