A Comprehensive Review and Evaluation of the Red Wolf (Canis Rufus) Recovery Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington Gray Wolf Conservation and Management 2016 Annual Report

WASHINGTON GRAY WOLF CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT 2016 ANNUAL REPORT A cooperative effort by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Confederated Colville Tribes, Spokane Tribe of Indians, USDA-APHIS Wildlife Services, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Photo: WDFW This report presents information on the status, distribution, and management of wolves in the State of Washington from January 1, 2016 through December 31, 2016. This report may be copied and distributed as needed. Suggested Citation: Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Confederated Colville Tribes, Spokane Tribe of Indians, USDA-APHIS Wildlife Services, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2017. Washington Gray Wolf Conservation and Management 2016 Annual Report. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Colville, WA, USA. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Gray wolves (Canis lupus) were classified as an endangered species in Washington under the provisions of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1973. In 2011, wolves in the eastern third of Washington were removed from federal protections under the ESA. Wolves in the western two- thirds of Washington continue to be protected under the ESA and are classified as an endangered species under federal law. In December 2011, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) Commission formally adopted the Wolf Conservation and Management Plan to guide recovery and management of gray wolves as they naturally recolonize the State of Washington. At present, wolves are classified as an endangered species under state law (WAC 232-12-014) throughout Washington regardless of federal status. Washington is composed of three recovery areas which include Eastern Washington, the Northern Cascades, and the Southern Cascades and Northwest Coast. -

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

Northeastern Coyote/Coywolf Taxonomy and Admixture: a Meta-Analysis

Way and Lynn Northeastern coyote taxonomy Copyright © 2016 by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. ISSN 1478-2677 Synthesis Northeastern coyote/coywolf taxonomy and admixture: A meta-analysis Jonathan G. Way1* and William S. Lynn2 1 Eastern Coyote Research, 89 Ebenezer Road, Osterville, MA 02655, USA. Email [email protected] 2 Marsh Institute, Clark University, Worcester, MA 01610, USA. Email [email protected] * Correspondence author Keywords: Canis latrans, Canis lycaon, Canis lupus, Canis oriens, cladogamy, coyote, coywolf, eastern coyote, eastern wolf, hybridisation, meta-analysis, northeastern coyote, wolf. Abstract A flurry of recent papers have attempted to taxonomically characterise eastern canids, mainly grey wolves Canis lupus, eastern wolves Canis lycaon or Canis lupus lycaon and northeastern coyotes or coywolves Canis latrans, Canis latrans var. or Canis latrans x C. lycaon, in northeastern North America. In this paper, we performed a meta-analysis on northeastern coyote taxonomy by comparing results across studies to synthesise what is known about genetic admixture and taxonomy of this animal. Hybridisation or cladogamy (the crossing between any given clades) be- tween coyotes, wolves and domestic dogs created the northeastern coyote, but the animal now has little genetic in- put from its parental species across the majority of its northeastern North American (e.g. the New England states) range except in areas where they overlap, such as southeastern Canada, Ohio and Pennsylvania, and the mid- Atlantic area. The northeastern coyote has roughly 60% genetic influence from coyote, 30% wolf and 10% domestic dog Canis lupus familiaris or Canis familiaris. There is still disagreement about the amount of eastern wolf versus grey wolf in its genome, and additional SNP genotyping needs to sample known eastern wolves from Algonquin Pro- vincial Park, Ontario to verify this. -

Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in English of Native American Origin Found Within

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Indian origin names, were eventually shortened to one-word names, making a few indistinguishable from names of non-Indian origin. Name Categories: Personal and family names of Indian origin contrast markedly with names of non-Indian Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in origin. English of Native American Origin 1. Personal and family names from found within Marquette University Christian saints (e.g. Juan, Johnson): Archival Collections natives- rare; non-natives- common 2. Family names from jobs (e.g. Oftentimes names of Native Miller): natives- rare; non-natives- American origin are based on objects common with descriptive adjectives. The 3. Family names from places (e.g. following list, which is not Rivera): natives- rare; non-native- comprehensive, comprises common approximately 1,000 name variations in 4. Personal and family names from English found within the Marquette achievements, attributes, or incidents University archival collections. The relating to the person or an ancestor names originate from over 50 tribes (e.g. Shot with two arrows): natives- based in 15 states and Canada. Tribal yes; non-natives- yes affiliations and place of residence are 5. Personal and family names from noted. their clan or totem (e.g. White bear): natives- yes; non-natives- no History: In ancient times it was 6. Personal or family names from customary for children to be named at dreams and visions of the person or birth with a name relating to an animal an ancestor (e.g. Black elk): natives- or physical phenominon. Later males in yes; non-natives- no particular received names noting personal achievements, special Tribes/ Ethnic Groups: Names encounters, inspirations from dreams, or are expressed according to the following physical handicaps. -

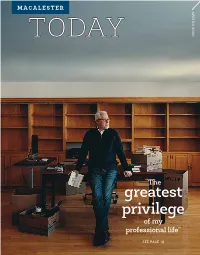

Download Issue PDF the Spring 2020 Issue of Macalester Today Is Available for Viewing In

MACALESTER SPRING 2020 TODAY “The greatest privilege of my professional life” SEE PAGE 18 MACALESTER STAFF EDITOR SPRING 2020 Rebecca DeJarlais Ortiz ’06 TODAY [email protected] ART DIRECTION The ESC Plan / theESCplan.com CLASS NOTES EDITOR Robert Kerr ’92 PHOTOGRAPHER David J. Turner CONTRIBUTING WRITER Julie Hessler ’85 ASSISTANT VICE PRESIDENT FOR MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Julie Hurbanis 14 18 26 32 36 CHAIR, BOARD OF TRUSTEES Jerry Crawford ’71 PRESIDENT FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Brian Rosenberg VICE PRESIDENT FOR ADVANCEMENT New Realities 10 Points of Struggle, Correspondence 2 D. Andrew Brown The COVID-19 pandemic forced Points of Pride 26 Household Words 3 ASSISTANT VICE PRESIDENT unprecedented, and often painful, Charting Macalester’s queer history FOR ENGAGEMENT decisions at Macalester this spring. over six decades 1600 Grand 4 Katie Ladas Macalester’s next president, Open LEFT TO RIGHT: PHOTO PROVIDED; DAVID J. TURNER; PHOTO PROVIDED; LISA HANEY, TRACEY BROWN TRACEY HANEY, LISA PROVIDED; TURNER; PHOTO J. DAVID PROVIDED; PHOTO RIGHT: TO LEFT MACALESTER TODAY (Volume 108, Number 2) “I Like to Dream Big” 14 Legends of the Night 32 Pantry, and the EcoHouse is published by Macalester College. It is mailed free of charge to alumni and friends Researcher and artist Jaye Sleep experts share their best of the college four times a year. Gardiner ’11 uses comics to advice—as well as some of their Class Notes 40 Circulation is 32,000. smash stereotypes and engage own sleep practice. You Said 41 TO UPDATE YOUR ADDRESS: new scientists. Email: [email protected] Waging Peace 36 Books 43 Call: 651-696-6295 or 1-888-242-9351 Write: Alumni Engagement Office, Macalester How to Practice Medicine Two alumni collaborate to support Weddings 45 College, 1600 Grand Ave., St. -

Vol. 76 Monday, No. 181 September 19, 2011 Pages 57897–58088

Vol. 76 Monday, No. 181 September 19, 2011 Pages 57897–58088 OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL REGISTER VerDate Mar 15 2010 18:22 Sep 16, 2011 Jkt 223001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\19SEWS.LOC 19SEWS sroberts on DSK5SPTVN1PROD with RULES II Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 181 / Monday, September 19, 2011 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records PUBLIC Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Subscriptions: Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and (Toll-Free) Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published Subscriptions: by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Paper or fiche 202–741–6005 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 202–741–6005 Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

Population Genomic Analysis of North American Eastern Wolves (Canis Lycaon) Supports Their Conservation Priority Status

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Population Genomic Analysis of North American Eastern Wolves (Canis lycaon) Supports Their Conservation Priority Status Elizabeth Heppenheimer 1,† , Ryan J. Harrigan 2,†, Linda Y. Rutledge 1,3 , Klaus-Peter Koepfli 4,5, Alexandra L. DeCandia 1 , Kristin E. Brzeski 1,6, John F. Benson 7, Tyler Wheeldon 8,9, Brent R. Patterson 8,9, Roland Kays 10, Paul A. Hohenlohe 11 and Bridgett M. von Holdt 1,* 1 Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA; [email protected] (E.H.); [email protected] (L.Y.R.); [email protected] (A.L.D); [email protected] (K.E.B.) 2 Center for Tropical Research, Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA; [email protected] 3 Biology Department, Trent University, Peterborough, ON K9L 1Z8, Canada 4 Center for Species Survival, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, Washington, DC 20008, USA; klauspeter.koepfl[email protected] 5 Theodosius Dobzhansky Center for Genome Bioinformatics, Saint Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia 6 School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI 49931, USA 7 School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68583, USA; [email protected] 8 Environmental & Life Sciences, Trent University, Peterborough, ON K9L 0G2, Canada; [email protected] (T.W.); [email protected] (B.R.P.) 9 Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Trent University, Peterborough, ON K9L 0G2, Canada 10 North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27601, USA; [email protected] 11 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID 83844, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally. -

Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Southeastern Pre-Columbian Canids Kristin E

Journal of Heredity, 2016, 287–293 doi:10.1093/jhered/esw002 Original Article Advance Access publication January 16, 2016 Brief Communication Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Southeastern Pre-Columbian Canids Kristin E. Brzeski, Melissa B. DeBiasse, David R. Rabon Jr, Michael J. Chamberlain, and Sabrina S. Taylor Downloaded from From the School of Renewable Natural Resources, Louisiana State University Agricultural Center and Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803 (Brzeski and Taylor); Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803 (DeBiasse); Endangered Wolf Center, P.O. Box 760, Eureka, MO 63025 (Rabon); and Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602 (Chamberlain). Address correspondence to Kristin E. Brzeski at the address above, or e-mail: [email protected]. http://jhered.oxfordjournals.org/ Received July 11, 2015; First decision August 17, 2015; Accepted January 4, 2016. Corresponding editor: Bridgett vonHoldt Abstract The taxonomic status of the red wolf (Canis rufus) is heavily debated, but could be clarified by examining historic specimens from the southeastern United States. We analyzed mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from 3 ancient (350–1900 year olds) putative wolf samples excavated from middens at Louisiana State University on June 17, 2016 and sinkholes within the historic red wolf range. We detected 3 unique mtDNA haplotypes, which grouped with the coyote mtDNA clade, suggesting that the canids inhabiting southeastern North America prior to human colonization from Europe were either coyotes, which would vastly expand historic coyote distributions, an ancient coyote–wolf hybrid, or a North American evolved red wolf lineage related to coyotes. Should the red wolf prove to be a distinct species, our results support the idea of either an ancient hybrid origin for red wolves or a shared common ancestor between coyotes and red wolves. -

Twisted Trails of the Wold West by Matthew Baugh © 2006

Twisted Trails of the Wold West By Matthew Baugh © 2006 The Old West was an interesting place, and even more so in the Wold- Newton Universe. Until fairly recently only a few of the heroes and villains who inhabited the early western United States had been confirmed through crossover stories as existing in the WNU. Several comic book miniseries have done a lot to change this, and though there are some problems fitting each into the tapestry of the WNU, it has been worth the effort. Marvel Comics’ miniseries, Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather was a humorous storyline, parodying the Kid’s established image and lampooning westerns in general. It is best known for ‘outing’ the Kid as a homosexual. While that assertion remains an open issue with fans, it isn’t what causes the problems with incorporating the story into the WNU. What is of more concern are the blatant anachronisms and impossibilities the story offers. We can accept it, but only with the caveat that some of the details have been distorted for comic effect. When the Rawhide Kid is established as a character in the Wold-Newton Universe he provides links to a number of other western characters, both from the Marvel Universe and from classic western novels and movies. It draws in the Marvel Comics series’ Blaze of Glory, Apache Skies, and Sunset Riders as wall as DC Comics’ The Kents. As with most Marvel and DC characters there is the problem with bringing in the mammoth superhero continuities of the Marvel and DC universes, though this is not insurmountable. -

USBC Approved Bowling Balls

USBC Approved Bowling Balls (See rulebook, Chapter VII, "USBC Equipment Specifications" for any balls manufactured prior to January 1991.) ** Bowling balls manufactured only under 13 pounds. 5/17/2011 Brand Ball Name Date Approved 900 Global Awakening Jul-08 900 Global BAM Aug-07 900 Global Bank Jun-10 900 Global Bank Pearl Jan-11 900 Global Bounty Oct-08 900 Global Bounty Hunter Jun-09 900 Global Bounty Hunter Black Jan-10 900 Global Bounty Hunter Black/Purple Feb-10 900 Global Bounty Hunter Pearl Oct-09 900 Global Break Out Dec-09 900 Global Break Pearl Jan-08 900 Global Break Point Feb-09 900 Global Break Point Pearl Jun-09 900 Global Creature Aug-07 900 Global Creature Pearl Feb-08 900 Global Day Break Jun-09 900 Global DVA Open Aug-07 900 Global Earth Ball Aug-07 900 Global Favorite May-10 900 Global Head Hunter Jul-09 900 Global Hook Dark Blue/Light Blue Feb-11 900 Global Hook Purple/Orange Pearl Feb-11 900 Global Hook Red/Yellow Solid Feb-11 900 Global Integral Break Black Nov-10 900 Global Integral Break Rose/Orange Nov-10 900 Global Integral Break Rose/Silver Nov-10 900 Global Link Jul-08 900 Global Link Black/Red Feb-09 900 Global Link Purple/Blue Pearl Dec-08 900 Global Link Rose/White Feb-09 900 Global Longshot Jul-10 900 Global Lunatic Jun-09 900 Global Mach One Blackberry Pearl Sep-10 900 Global Mach One Rose/Purple Pearl Sep-10 900 Global Maniac Oct-08 900 Global Mark Roth Ball Jan-10 900 Global Missing Link Black/Red Jul-10 900 Global Missing Link Blackberry/Silver Jul-10 900 Global Missing Link Blue/White Jul-10 900 Global -

Holding the Wolf by the Ears: the Conservation of the Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf in Yellowstone National Park

Land & Water Law Review Volume 27 Issue 1 Article 2 1992 Holding the Wolf by the Ears: The Conservation of the Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf in Yellowstone National Park Timothy B. Strauch Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uwyo.edu/land_water Recommended Citation Strauch, Timothy B. (1992) "Holding the Wolf by the Ears: The Conservation of the Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf in Yellowstone National Park," Land & Water Law Review: Vol. 27 : Iss. 1 , pp. 33 - 81. Available at: https://scholarship.law.uwyo.edu/land_water/vol27/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Law Archive of Wyoming Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Land & Water Law Review by an authorized editor of Law Archive of Wyoming Scholarship. Strauch: Holding the Wolf by the Ears: The Conservation of the Northern Ro University of Wyoming College of Law LAND AND WATER LAW REVIEW VOLUME XXVII 1992 NUMBER 1 HOLDING THE WOLF BY THE EARS: THE CONSERVATION OF THE NORTHERN ROCKY MOUNTAIN WOLF IN YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK Timothy B. Strauch* I. INTRODUCTION ....................................... 34 II. HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ON THE WOLF ................ 36 A. The Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf ............. 36 B. Early Reports and Killings of the Wolf in the Northern Rocky Mountain Area ................. 38 C. Wolf Population Decline Under Severe Predator Control Programs .............................. 40 D. The Wolf and Wolf Control in Yellowstone N ational P ark ................................. 42 III. WOLF RECOVERY AND CONSERVATION ................... 44 A. Current Status of the Northern Rocky Mountain W o lf ..... .. ....... .. ........ .. ... 4 4 B. The Endangered Species Act ................... 47 C. The Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery Plan 51 D. -

Undergraduate Student Yes Characterizing a Putative

Alex Abbott 41 Ouachita Baptist University Biology (BI) Undergraduate Student Yes Characterizing a Putative Mycobacteriophage Toxin-Antitoxin System Alex Abbott, Ruth Plymale Bacteria are under recurring threat of bacteriophage infection and possess defense systems to fight off these viruses. Surprisingly, these anti-phage defense systems may be encoded by prophage, bacteriophage DNA that has been integrated into a bacterial cell, thereby protecting the host bacterial cell from superinfection. Mycobacteriophage Xeno encodes a putative toxin-antitoxin (TA) system expected to defend against mycobacteriophage infection when Xeno is incorporated as a prophage in Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155, forming the lysogen Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155 (Xeno). The goal of this research is to identify which mycobacteriophage this putative TA system defends against, by screening more than 60 mycobacteriophage on M. smegmatis mc2155 and M. smegmatis mc2155(Xeno). Individual bacteriophage will be spotted on lawns of M. smegmatis mc2155 or M. smegmatis mc2155 (Xeno) and the number of plaQues will be counted and used to determine infection rate. If a phage produces 10x to 1000x more plaQues on M. smegmatis mc2155 than M. smegmatis mc2155 (Xeno), we will conclude that this phage is defended against by the TA system of the Xeno prophage. We will present the findings of our phage screening trials and our conclusions about the defensive range of the Xeno TA system. Joseph Akers 97 University of Central Arkansas Physics (PH) Undergraduate Student Yes Process Engineering: 3 Dimensional ColorSpace Correction Joseph Akers This project was developed to analyZe information pertaining to the color of an industrially manufactured product and provide corrective measures to achieve an ideal product.