Na Yadrayadravaki Case Study of Community Led Resilience During TC Gita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Are Kai Tonga”

5. “We are Kai Tonga” The islands of Moala, Totoya and Matuku, collectively known as the Yasayasa Moala, lie between 100 and 130 kilometres south-east of Viti Levu and approximately the same distance south-west of Lakeba. While, during the nineteenth century, the three islands owed some allegiance to Bau, there existed also several family connections with Lakeba. The most prominent of the few practising Christians there was Donumailulu, or Donu who, after lotuing while living on Lakeba, brought the faith to Moala when he returned there in 1852.1 Because of his conversion, Donu was soon forced to leave the island’s principal village, Navucunimasi, now known as Naroi. He took refuge in the village of Vunuku where, with the aid of a Tongan teacher, he introduced Christianity.2 Donu’s home island and its two nearest neighbours were to be the scene of Ma`afu’s first military adventures, ostensibly undertaken in the cause of the lotu. Richard Lyth, still working on Lakeba, paid a pastoral visit to the Yasayasa Moala in October 1852. Despite the precarious state of Christianity on Moala itself, Lyth departed in optimistic mood, largely because of his confidence in Donu, “a very steady consistent man”.3 He observed that two young Moalan chiefs “who really ruled the land, remained determined haters of the truth”.4 On Matuku, which he also visited, all villages had accepted the lotu except the principal one, Dawaleka, to which Tui Nayau was vasu.5 The missionary’s qualified optimism was shattered in November when news reached Lakeba of an attack on Vunuku by the two chiefs opposed to the lotu. -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

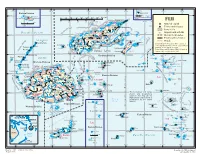

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT ISSUES for FIJI – Exploration & Exploitation of Deep Sea Minerals

ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT ISSUES for FIJI – Exploration & Exploitation of Deep Sea Minerals 29 Nov – 2 Dec 2011 Denarau, Nadi, Fiji Mala Finau – Director Mineral Development INTRODUCTION • Fiji Island is located in the South-West Pacific Ocean • Comprised of over 322 islands • Total land area covers about 18,000 km² spread over 1.3 million km² of South Pacific Ocean • Volcanic origin but no active volcanoes • High central mountain ranges with several large rivers leading down to coastal plains, then beaches and mangrove swamps surrounded by shallow water and coral reefs • Tropical Climate – 2 distinct seasons • Nov – Apr : Wet & Cyclone Season • May – Oct : Dry, Cold What We Have • Waters of the Fiji Islands contain 3.12% of the world’s coral reefs including the Great Sea Reef, the third largest in the world. • Marine life includes over 390 known species of coral and 12,000 varieties of fish of which 7 are endemic. • Fiji waters are spawning ground for many species including the endangered hump head wrasse and bump head parrot fish. • Five of the world’s seven species of sea turtle inhabit Fiji water. • Marine Mineral Resources • Multi–Stakeholder agencies including communities involvement What We Have • Dedicated Govt. Depts. (Environment, Mineral Resources etc) • Dedicated environment units • Policy – Offshore Mineral Policy • Legislation – EMA (2005), Mining Act (1978), MEEB (2006) • ~ 50 Mineral Exploration Licenses (On-shore) • 3 Mines (On-shore) • 17 Deep Sea Mineral Exploration Licenses • “Interest” in the ISA (‘THE AREA’) Types of -

Filling the Gaps: Identifying Candidate Sites to Expand Fiji's National Protected Area Network

Filling the gaps: identifying candidate sites to expand Fiji's national protected area network Outcomes report from provincial planning meeting, 20-21 September 2010 Stacy Jupiter1, Kasaqa Tora2, Morena Mills3, Rebecca Weeks1,3, Vanessa Adams3, Ingrid Qauqau1, Alumeci Nakeke4, Thomas Tui4, Yashika Nand1, Naushad Yakub1 1 Wildlife Conservation Society Fiji Country Program 2 National Trust of Fiji 3 ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University 4 SeaWeb Asia-Pacific Program This work was supported by an Early Action Grant to the national Protected Area Committee from UNDP‐GEF and a grant to the Wildlife Conservation Society from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation (#10‐94985‐000‐GSS) © 2011 Wildlife Conservation Society This document to be cited as: Jupiter S, Tora K, Mills M, Weeks R, Adams V, Qauqau I, Nakeke A, Tui T, Nand Y, Yakub N (2011) Filling the gaps: identifying candidate sites to expand Fiji's national protected area network. Outcomes report from provincial planning meeting, 20‐21 September 2010. Wildlife Conservation Society, Suva, Fiji, 65 pp. Executive Summary The Fiji national Protected Area Committee (PAC) was established in 2008 under section 8(2) of Fiji's Environment Management Act 2005 in order to advance Fiji's commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)'s Programme of Work on Protected Areas (PoWPA). To date, the PAC has: established national targets for conservation and management; collated existing and new data on species and habitats; identified current protected area boundaries; and determined how much of Fiji's biodiversity is currently protected through terrestrial and marine gap analyses. -

Vanua Levu Vita Levu Suva

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 0 10 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Coral reefs Sasa Nasea l Cobia e n n Airports and airfields Pacific Ocean Navidamu Rabi a Labasa e y Nailou h v a C 16° 30’ Natua ro B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld ka o Nabiti Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu Bua conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua a parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. s Yandua Nadivakarua Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Nanuku Passage Viwa Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata tu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Wayalevu Malake - Vanua Balavu I- Nasau N r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna C H Kuata Tavua Vaileka h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Ra n Mago N Sorokoba n Lomaiviti -

Rapid Biological Assessment Survey of Southern Lau, Fiji

R BAPID IOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT SURVEY OF SOUTHERN LAU, FIJI BI ODIVERSITY C ONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 22 © 2013 Cnes/Spot Image BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES Rapid Biological Assessment Survey of Southern 22 Lau, Fiji Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series is published by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and Conservation International Pacific Islands Program (CI-Pacific) PO Box 2035, Apia, Samoa T: + 685 21593 E: [email protected] W: www.conservation.org The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. Conservation International Pacific Islands Program. 2013. Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series 22: Rapid Biological Assessment Survey of Southern Lau, Fiji. Conservation International, Apia, Samoa Authors: Marika Tuiwawa & Prof. William Aalbersberg, Institute of Applied Sciences, University of the South Pacific, Private Mail Bag, Suva, Fiji. Design/Production: Joanne Aitken, The Little Design Company, www.thelittledesigncompany.com Cover Photograph: Fiji and the Lau Island group. Source: Google Earth. Series Editor: Leilani Duffy, Conservation International Pacific Islands Program Conservation International is a private, non-profit organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. OUR MISSION Building upon a strong foundation of science, partnership and field demonstration, Conservation International empowers societies to responsibly and sustainably care for nature for the well-being of humanity. ISBN 978-982-9130-22-8 © 2013 Conservation International All rights reserved. -

Vanua Levu Viti Levu

MA019 Index of Maps Page Page 2 Number Page Name Number Page Name 1 1 Rotuma 48 South Vanua Balavu Fiji: 2 Cikobia 49 Mana and Malolo Lailai S ° 3 6 3 Vatauna 50 Nadi 1 Cyclone Winston- 4 Kia 51 West Central Viti Levu 8 Index to 1:100 000 5 Mouta 52 Central Viti Levu 4 5 6 7 6 Dogotuki 53 Laselevu 16 Topographical Maps 7 Nagasauva 54 Korovou Labasa 8 Naqelelevu 55 Levuka Northern 10 11 12 13 14 15 9 Yagaga 56 Wakaya and Batiki 9 Index to 1:100 000 Topographical 10 Macuata 57 Nairai Vanua Levu 23 24 25 Series (MA003) with numbers and 11 Sasa 58 Cicia 17 19 20 21 22 26 names 12 Labasa 59 Tuvuca and Katafaga Yasawa 18 Savusavu 13 Saqan 60 West Viti Levu 31 14 Rabi 61 Narewa 27 28 29 30 15 Yanuca 62 South Central Viti Levu 37 38 Northern 16 Nukubasaga 63 East Cental Viti Levu 33 34 35 Lau Rotuma 17 Yasawa North 64 Nausori 32 36 18 Yadua 65 Gau Vaileka 46 47 48 19 Bua 66 Nayau Tavua 42 43 45 Central 39 40 41 Ba 44 20 Vanua Levu 67 Eastern Atolls Western Lautoka Vatukoula Lamaiviti 21 Wailevu 68 South West Viti Levu 59 49 50 53 54 55 56 58 22 Savusavu 69 Sigatoka Viti Levu 52 57 23 Tonulou 70 Queens Road 51 Korovou Nadi 67 24 Wainikeli 71 Navau S 66 ° 8 60 61 62 Central FIJI 25 Laucala 72 Suva 1 63 64 65 26 Wallagi Lala 73 Lakeba Sigatoka 27 Yasawa South 74 Vatulele 72 68 69 70 71 73 28 Vuya 75 Yanuca and Bega Vanua Levu 77 29 South 76 Vanua Vatu 75 76 30 Waisa 77 Alwa and Oneata 74 Taveuni 79 31 South 78 Dravuni 80 81 78 Viwa and Eastern 32 Waya 79 Moala 85 86 Naiviti and 82 83 84 33 Narara 80 Tavu Na Siel 34 Naba 81 Moce, Komu and Ororua -

Half Year Report (Due 31 October 2009)

Darwin Initiative: Half Year Report (due 31 October 2009) Project Ref. No. 15/007 Project Title Focus for Fiji: Insect Inventories for Biodiversity Assessment Country(ies) Fiji UK Organisation University of Sussex Collaborator(s) Prof. W. Aalbersberg, University of the South Pacific Project Leader Dr A.J.A. Stewart Report date 27th October 2009 Report No. (HYR HYR 4 1/2/3/4) Project website http://www.usp.ac.fj/index.php?id=7040 1. Outline progress over the last 6 months (April – September) against the agreed baseline timetable for the project (if your project has started less than 6 months ago, please report on the period since start up). Achievements, April – September 2009 Training staff: Scale Insect Taxonomy Workshop held from the 13th-15th July, 2009 at USP, Fiji by UK expert Dr. Chris Hodgson of Cardiff Museum, Wales. A total of 18 participants attended the 3 day workshop, including USP postgraduates studying entomology and scientists from the Forestry Department, Agriculture Department and Quarantine Department. The workshop included laboratory-based training in identification and training in field collection techniques using a farm in Wainibuku and a Forest Reserve in Savura, Viti Levu. Participants were presented with training certificates at the end of the workshop by the Director of IAS, Prof. Bill Aalbersberg. Following the workshop, further training in field collecting and taxonomy of scale insects was provided during visits to two islands: Taveuni and Kadavu. Mr Maxwell Barclay, an expert coleopterist in the Entomology Department at the Natural History Museum in London, has agreed to run a beetle training course in Fiji for this project in early 2009. -

Fiji Shipping Franchise Scheme Presentationpresentation Outlineoutline

FIJI SHIPPING FRANCHISE SCHEME PRESENTATIONPRESENTATION OUTLINEOUTLINE ¾ Background ¾ Shipping Routes ¾ Fiji Shipping Franchise ¾ Conclusion BACKGROUND ¾POPULATION – 830,000 ¾100/332 ISLANDS POPULATED ¾MARITIME AREA [EEZ] – 1.3MILLION SQKM ¾ REGISTERED VESSELS – 587 [April 2012] ¾28 GOVT WHARVES AND JETTIES SHIPPINGSHIPPING ROUTESROUTES ClassificationClassification ofof ShippingShipping Routes:Routes: i.i. EconomicalEconomical RoutesRoutes ••InvolveInvolve withwith HighHigh CapacityCapacity andand VolumeVolume ofof CargosCargos andand PassengersPassengers ii.ii. UneconomicalUneconomical RoutesRoutes ••LessLess CargoCargo andand PassengersPassengers 4 ECONOMICAL ROUTES MV Lomaiviti Princess 1 & II MV Westerland MV Spirit of Harmony MV Sinu I Wasa Route Vessel Vessel Type Levuka/ Natovi/ Spirit of RORO Nabouwalu Harmony Suva /Levuka Sinu I Wasa RORO Suva/Koro/ Lomaiviti RORO Savusavu/Taveuni Princess I & II Natovi/ Savusavu Westerland RORO Suva/ Kadavu Sinu I Wasa RORO Lomaiviti RORO Princess II UNECONOMICAL ROUTES MV Lau Trader MV Uluinabukelevu MV Lady Sandy MV YII GSS Iloilovatu ROUTE ISLAND PORTS VESSEL Northern Lau I Suva – Vanuabalavu – Cicia – Suva. Northern Lau II Suva ‐ Lakeba –Nayau – Tuvuca ‐ Cikobia ‐ MV Lau Trader Yacata – Suva. Upper Suva ‐ Lakeba –Oneata –Moce ‐ Komo – MV Lady Sandy Southern Lau Namuka i Lau and Vanua Vatu – Suva. Lower Suva ‐ Kabara – Fulaga –Ogea ‐ Vatoa – MV Lau Trader Southern Lau Ono –i‐ Lau – Suva. Kadavu Suva ‐ Kadavu ‐ Baba Tokalau , Kadavu. MV Uluinabukelevu (3months) Rotuma Suva ‐ O’inafa Port – Suva. Yasawa Malolo Lautoka – Yasawa‐ i‐ rara –Waya & Viwa ‐ MV YII Lautoka Yasayasa Suva ‐ Moala –Matuku and Totoya – MV Lady Sandy LomaivitiMoala 1 SuvaSuva. ‐ Gau –Nairai –Batiki ‐ Suva MV Lady Sandy Lomaiviti 2 Suva –Gau – Suva. FIJI SHIPPING FRANCHISE SCHEME ¾ A shipping assistance provided by Government for shipping services in uneconomical shipping routes in the Maritime province. -

Tabu Soro: Building Resilient Workplaces in Fiji

Tabu Soro: Building Resilient Workplaces in Fiji Wormald Case Study March 2021 IN PARTNERSHIP WITH ABOUT IFC IFC—a member of the World Bank Group—is the largest global development institution focused on the private sector in emerging markets. We work in more than 100 countries, using our capital, expertise, and influence to create markets and opportunities in developing countries. In fiscal year 2020, we invested $22 billion in private companies and financial institutions in developing countries, leveraging the power of the private sector to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity. For more information, visit www.ifc.org. COPYRIGHT NOTICE © International Finance Corporation 2021. All rights reserved. 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 Internet: www.ifc.org The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the content included in this work, or for the conclusions or judgments described herein, and accepts no responsibility or liability for any omissions or errors (including, without limita- tion, typographical errors and technical errors) in the content whatsoever or for reliance thereon. PACIFIC PARTNERSHIP IFC’s work in Fiji is guided by the Fiji Partnership. Australia, New Zealand and IFC are working together through the Partnership to stimulate private sector investment and reduce poverty in Fiji. 2 TABU SORO: BUILDING RESILIENT WORKPLACES IN FIJI Tabu Soro: Building Resilient Workplaces in Fiji OVERVIEW Motusa Rotuma FIJI SELECTED CITIES AND TOWNS ROTUMA DEPENDENCY DIVISION CAPITALS Driven by the principle that by looking after staff, the staff will NATIONAL CAPITAL RIVERS look after the company, Wormald embarked on a process to MAIN ROADS DIVISION BOUNDARIES strengthen the organization’s resilience and build a culture of INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN respect. -

Biophysically Special, Unique Marine Areas of FIJI © Stuart Chape

BIOPHYSICALLY SPECIAL, UNIQUE MARINE AREAS OF FIJI © Stuart Chape BIOPHYSICALLY SPECIAL, UNIQUE MARINE AREAS OF FIJI EFFECTIVE MANAGEMENT Marine and coastal ecosystems of the Pacific Ocean provide benefits for all people in and beyond the region. To better understand and improve the effective management of these values on the ground, Pacific Island Countries are increasingly building institutional and personal capacities for Blue Planning. But there is no need to reinvent the wheel, when learning from experiences of centuries of traditional management in Pacific Island Countries. Coupled with scientific approaches these experiences can strengthen effective management of the region’s rich natural capital, if lessons learnt are shared. The MACBIO project collaborates with national and regional stakeholders towards documenting effective approaches to sustainable marine resource management and conservation. The project encourages and supports stakeholders to share tried and tested concepts and instruments more widely throughout partner countries and the Oceania region. This report outlines the process undertaken to define and describe the special, unique marine areas of Fiji. These special, unique marine areas provide an important input to decisions about, for example, permits, licences, EIAs and where to place different types of marine protected areas, Locally-Managed Marine Area and tabu sites in Fiji. For a copy of all reports and communication material please visit www.macbio-pacific.info. MARINE ECOSYSTEM MARINE SPATIAL PLANNING EFFECTIVE MANAGEMENT SERVICE VALUATION BIOPHYSICALLY SPECIAL, UNIQUE MARINE AREAS OF FIJI AUTHORS: Helen Sykes1, Jimaima Le Grand2, Kate Davey3, Sahar Noor Kirmani4, Sangeeta Mangubhai5, Naushad Yakub3, Hans Wendt3, Marian Gauna3, Leanne Fernandes3 2018 SUGGESTED CITATION: Sykes H, Le Grand J, Davey K, Kirmani SN, Mangubhai S, Yakub N, Wendt H, Gauna M, Fernandes L (2018) Biophysically special, unique marine areas of Fiji.