Bermudagrass Stem Maggot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Apple Maggot [Rhagoletis Pomonella (Walsh)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3187/apple-maggot-rhagoletis-pomonella-walsh-143187.webp)

Apple Maggot [Rhagoletis Pomonella (Walsh)]

Published by Utah State University Extension and Utah Plant Pest Diagnostic Laboratory ENT-06-87 November 2013 Apple Maggot [Rhagoletis pomonella (Walsh)] Diane Alston, Entomologist, and Marion Murray, IPM Project Leader Do You Know? • The fruit fly, apple maggot, primarily infests native hawthorn in Utah, but recently has been found in home garden plums. • Apple maggot is a quarantine pest; its presence can restrict export markets for commercial fruit. • Damage occurs from egg-laying punctures and the larva (maggot) developing inside the fruit. • The larva drops to the ground to spend the winter as a pupa in the soil. • Insecticides are currently the most effective con- trol method. • Sanitation, ground barriers under trees (fabric, Fig. 1. Apple maggot adult on plum fruit. Note the F-shaped mulch), and predation by chickens and other banding pattern on the wings.1 fowl can reduce infestations. pple maggot (Order Diptera, Family Tephritidae; Fig. A1) is not currently a pest of commercial orchards in Utah, but it is regulated as a quarantine insect in the state. If it becomes established in commercial fruit production areas, its presence can inflict substantial economic harm through loss of export markets. Infesta- tions cause fruit damage, may increase insecticide use, and can result in subsequent disruption of integrated pest management programs. Fig. 2. Apple maggot larva in a plum fruit. Note the tapered head and dark mouth hooks. This fruit fly is primarily a pest of apples in northeastern home gardens in Salt Lake County. Cultivated fruit is and north central North America, where it historically more likely to be infested if native hawthorn stands are fed on fruit of wild hawthorn. -

Myiasis During Adventure Sports Race

DISPATCHES reexamined 1 day later and was found to be largely healed; Myiasis during the forming scar remained somewhat tender and itchy for 2 months. The maggot was sent to the Finnish Museum of Adventure Natural History, Helsinki, Finland, and identified as a third-stage larva of Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel), Sports Race the New World screwworm fly. In addition to the New World screwworm fly, an important Old World species, Mikko Seppänen,* Anni Virolainen-Julkunen,*† Chrysoimya bezziana, is also found in tropical Africa and Iiro Kakko,‡ Pekka Vilkamaa,§ and Seppo Meri*† Asia. Travelers who have visited tropical areas may exhibit aggressive forms of obligatory myiases, in which the larvae Conclusions (maggots) invasively feed on living tissue. The risk of a Myiasis is the infestation of live humans and vertebrate traveler’s acquiring a screwworm infestation has been con- animals by fly larvae. These feed on a host’s dead or living sidered negligible, but with the increasing popularity of tissue and body fluids or on ingested food. In accidental or adventure sports and wildlife travel, this risk may need to facultative wound myiasis, the larvae feed on decaying tis- be reassessed. sue and do not generally invade the surrounding healthy tissue (1). Sterile facultative Lucilia larvae have even been used for wound debridement as “maggot therapy.” Myiasis Case Report is often perceived as harmless if no secondary infections In November 2001, a 41-year-old Finnish man, who are contracted. However, the obligatory myiases caused by was participating in an international adventure sports race more invasive species, like screwworms, may be fatal (2). -

Cattle-Diseases-Flies.Pdf

FLIES Flies cause major economic production losses in livestock. They attack, irritate and feed on cattle and other animals. Flies can be involved in the transmission of diseases and blowflies are important due to the damage caused by their maggot stages. Their life cycles are completed very quickly, giving rise to very rapid population expansions, highlighting the need to apply fly control medicines early in the season. DEC JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV Adult blowflies Young adult Eggs blowflies laid in wool <24 hours 3–7 days Blow fly life cycle Pupae First-stage (in soil) larvae 5–6 days (maggots) 4–6 days Third-stage larvae Second-stage (maggots) larvae (maggots) During feeding, the headfly Hydrotaea irritans causes considerable irritation which may result in self trauma. This fly has also been implicated in the transmission of bacteria responsible for summer mastitis, a potentially serious disease leading to the loss of milk production and, in severe cases, the life of the animal. Face flies such as Musca autumnalis feed on lachrymal secretions and have been implicated in the transmission of the causative bacteria for New Forest Eye. FOR ANIMALS. FOR HEALTH. FOR YOU. FLY EMERGENCE AND POPULATION GROWTHS • Fly populations vary from season to season • Different species emerge at differing times of the year Head Fly Face Fly Horn Fly Horse Fly Stable Fly April May June July August September October Head files Scientific name Hydrotaea irritans Cause ‘black cap’ or ‘broken head’ in horned sheep. Problems caused Transmit summer mastitis in cattle Feed on sweat and secretions from the nose, eyes, udder Feeding and wounds June to October. -

Evaluating the Effects of Temperature on Larval Calliphora Vomitoria (Diptera: Calliphoridae) Consumption

Evaluating the effects of temperature on larval Calliphora vomitoria (Diptera: Calliphoridae) consumption Kadeja Evans and Kaleigh Aaron Edited by Steven J. Richardson Abstract: Calliphora vomitoria (Diptera: Calliphoridae) are responsible for more cases of myiasis than any other arthropods. Several species of blowfly, including Cochliomyia hominivorax and Cocholiomya macellaria, parasitize living organisms by feeding on healthy tissues. Medical professionals have taken advantage of myiatic flies, Lucillia sericata, through debridement or maggot therapy in patients with necrotic tissue. This experiment analyzes how temperature influences blue bottle fly, Calliphora vomitoria. consumption of beef liver. After rearing an egg mass into first larval instars, ten maggots were placed into four containers making a total of forty maggots. One container was exposed to a range of temperatures between 18°C and 25°C at varying intervals. The remaining three containers were placed into homemade incubators at constant temperatures of 21°C, 27°C and 33°C respectively. Beef liver was placed into each container and weighed after each group pupation. The mass of liver consumed and the time until pupation was recorded. Three trials revealed that as temperature increased, the average rate of consumption per larva also increased. The larval group maintained at 33°C had the highest consumption with the shortest feeding duration, while the group at 21°C had lower liver consumption in the longest feeding period. Research in this experiment was conducted to understand the optimal temperature at which larval consumption is maximized whether in clinical instances for debridement or in myiasis cases. Keywords: Calliphora vomitoria, Calliphoridae, myiasis, consumption, debridement As an organism begins to decompose, target open wounds or necrotic tissue. -

Forensic Entomology: the Use of Insects in the Investigation of Homicide and Untimely Death Q

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. Winter 1989 41 Forensic Entomology: The Use of Insects in the Investigation of Homicide and Untimely Death by Wayne D. Lord, Ph.D. and William C. Rodriguez, Ill, Ph.D. reportedly been living in and frequenting the area for several Editor’s Note weeks. The young lady had been reported missing by her brother approximately four days prior to discovery of her Special Agent Lord is body. currently assigned to the An investigation conducted by federal, state and local Hartford, Connecticut Resident authorities revealed that she had last been seen alive on the Agency ofthe FBi’s New Haven morning of May 31, 1984, in the company of a 30-year-old Division. A graduate of the army sergeant, who became the primary suspect. While Univercities of Delaware and considerable circumstantial evidence supported the evidence New Hampshin?, Mr Lordhas that the victim had been murdered by the sergeant, an degrees in biology, earned accurate estimation of the victim’s time of death was crucial entomology and zoology. He to establishing a link between the suspect and the victim formerly served in the United at the time of her demise. States Air Force at the Walter Several estimates of postmortem interval were offered by Army Medical Center in Reed medical examiners and investigators. These estimates, Washington, D.C., and tire F however, were based largely on the physical appearance of Edward Hebert School of the body and the extent to which decompositional changes Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland. had occurred in various organs, and were not based on any Rodriguez currently Dr. -

Bird's Nest Screwworm

Beneficial Species Profile Photo credit: Copyright © 2013 Mardon Erbland, bugguide.net Common Name: Bird’s Nest Screwworm Fly / Holarctic Blow Fly Scientific Name: Protophormia terraenovae Order and Family: Diptera / Calliphoridae Size and Appearance: Length (mm) Appearance Egg 1mm Larva/Nymph Small and white, with about 12 1-12mm segments Adult Dark anterior thoracic spiracle, dark metallic blue in color. 8-12 mm Similar to Phormia regina, however P. terraenovae has longer dorsocentral bristles with acrostichal (set in highest row) bristles short or absent. Pupa (if applicable) 8-9mm Type of feeder (Chewing, sucking, etc.): Sponging in adults / Mouthhooks in larvae Host/s: Larvae develop primarily in carrion. Description of Benefits (predator, parasitoid, pollinator, etc.): This insect is used in Forensic and Medical fields. Maggot Debridement Therapy is the use of maggots to clean and disinfect necrotic flesh wounds. To be usable in this practice, the creature must only target the necrotic tissues. This species ‘fits the bill.’ P. terraenovae is known to produce antibiotics as they feed, helping to fight some infections. P. terraenovae is one of the only blow fly species usable in this way. Blow flies are also one of the first species to arrive on a cadaver. Due to early arrival, they can be the most informative for postmortem investigations. Scientists will collect, note, rear, and identify the species to determine life cycles and developmental rates. Once determined, they can calculate approximate death. This species is also known to cause myiasis in livestock, causing wound strike and death. References: Species Protophormia terraenovae. (n.d.). Retrieved September 04, 2020, from https://bugguide.net/node/view/862102 Byrd, J. -

Forensic Entomology

Forensic Entomology Definition: Forensic Entomology is the application of the study of insects and other arthropods to legal issues. It is divided into three areas: 1) urban, 2) stored products, and 3) medico-legal. It is the medico-legal area that receives the most attention (and is the most interesting). In the medico-legal field insects have been used to 1) locate bodies or body parts, 2) estimate the time of death or postmortem interval (PMI), 3) determine the cause of death, 4) determine whether the body has been moved after death, 5) identify a criminal suspect, and 6) identify the geographic origin of contraband. In this lecture we will discuss the kind of entomological data collected in forensic cases and how these data are used as evidence in criminal proceedings. Case studies will be used to illustrate the use of entomological data. Evidence Used in Forensic Entomology • Presence of suspicious insects in the environment or on a criminal suspect. Adults of carrion-feeding insects are usually found in a restricted set of habitats: 1) around adult feeding sites (i.e., flowers), or 2) around oviposition sites (i.e., carrion). Insects, insect body parts or insect bites on criminal suspects can be used to place them at scene of a crime or elsewhere. • Developmental stages of insects at crime scene. Detailed information on the developmental stages of insects on a corpse can be used to estimate the time of colonization. • Succession of insect species at the crime scene. Different insect species arrive at corpses at different times in the decompositional process. -

Use of DNA Sequences to Identify Forensically Important Fly Species in the Coastal Region of Central California (Santa Clara County)

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Summer 2013 Use of DNA Sequences to Identify Forensically Important Fly Species in the Coastal Region of Central California (Santa Clara County) Angela T. Nakano San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Nakano, Angela T., "Use of DNA Sequences to Identify Forensically Important Fly Species in the Coastal Region of Central California (Santa Clara County)" (2013). Master's Theses. 4357. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.8rxw-2hhh https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4357 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USE OF DNA SEQUENCES TO IDENTIFY FORENSICALLY IMPORTANT FLY SPECIES IN THE COASTAL REGION OF CENTRAL CALIFORNIA (SANTA CLARA COUNTY) A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Biological Sciences San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Angela T. Nakano August 2013 ©2013 Angela T. Nakano ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled USE OF DNA SEQUENCES TO IDENTIFY FORENSICALLY IMPORTANT FLY SPECIES IN THE COASTAL REGION OF CENTRAL CALIFORNIA (SANTA CLARA COUNTY) by Angela T. Nakano APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY August 2013 Dr. Jeffrey Honda Department of Biological Sciences Dr. -

Role of Maggot in Medical Treatment F Amrita Narayan* Department of Phychiatry, the Canberra Hospital, Australia

Herpe y & tolo log gy o : th C i u n r r r e O n , t y R g e o l s Entomology, Ornithology & o e a m r o c t h n E ISSN: 2161-0983 Herpetology: Current Research Editorial Role of Maggot in Medical Treatment f Amrita Narayan* Department of Phychiatry, The Canberra Hospital, Australia larvae of Calliphorid flies of the species Phaenicia sericata INTRODUCTION (previously called Lucilia sericata).This species of maggots is A maggot is the larva of a fly (order Diptera); its miles maximum extensively used withinside the international as implemented mainly to the larvae of Brachycera flies, together properly however it's miles doubtful whether or not it's miles the with houseflies, cheese flies, and blowflies, as opposed to larvae best species cleared for advertising outdoor of the United States. of the Nematocera, together with mosquitoes and Crane flies. A They feed at the useless or necrotic tissue, leaving sound tissue 2012 have a look at anticipated the populace of maggots in in large part unharmed. Studies have additionally proven that North America by myself to be in extra of 3×1017. Maggot" isn't maggots kill microorganism. There are 3 midgut lysozymes of P. a technical time period and need to now no longer be taken as sericata which have been proven to reveal antibacterial such; in lots of well-known textbooks of entomology, it does now consequences in maggot debridement remedy. The have a look no longer seem with inside the index at all. In many non- at proven that almost all of gram-effective microorganism had technical texts, the time period is used for insect larvae in been destroyed in vivo in the precise segment of the P. -

Test Key to British Blowflies (Calliphoridae) And

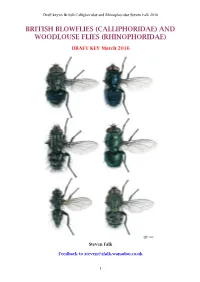

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016 BRITISH BLOWFLIES (CALLIPHORIDAE) AND WOODLOUSE FLIES (RHINOPHORIDAE) DRAFT KEY March 2016 Steven Falk Feedback to [email protected] 1 Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016 PREFACE This informal publication attempts to update the resources currently available for identifying the families Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae. Prior to this, British dipterists have struggled because unless you have a copy of the Fauna Ent. Scand. volume for blowflies (Rognes, 1991), you will have been largely reliant on Van Emden's 1954 RES Handbook, which does not include all the British species (notably the common Pollenia pediculata), has very outdated nomenclature, and very outdated classification - with several calliphorids and tachinids placed within the Rhinophoridae and Eurychaeta palpalis placed in the Sarcophagidae. As well as updating keys, I have also taken the opportunity to produce new species accounts which summarise what I know of each species and act as an invitation and challenge to others to update, correct or clarify what I have written. As a result of my recent experience of producing an attractive and fairly user-friendly new guide to British bees, I have tried to replicate that approach here, incorporating lots of photos and clear, conveniently positioned diagrams. Presentation of identification literature can have a big impact on the popularity of an insect group and the accuracy of the records that result. Calliphorids and rhinophorids are fascinating flies, sometimes of considerable economic and medicinal value and deserve to be well recorded. What is more, many gaps still remain in our knowledge. -

Adult Longevity of Chrysomya Rufifacies (Macquart) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) by Sex Catherine Collins and Dr

Adult Longevity of Chrysomya rufifacies (Macquart) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) by Sex Catherine Collins and Dr. Adrienne Brundage Editor Kristina Gonzalez Abstract: Chrysomya rufifacies (Macquart) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) is a species of blow fly with significance to the field of forensic entomology due to its use in establishing post mortem intervals. The species also plays a large role in medicine through maggot debridement therapy (MDT). Knowing the lifespan of Ch. rufifacies is vital to determining post mortem interval. To better understand Ch. rufifacies lifespans, this study seeks to determine if the adult lifespan of male Ch. rufifacies differs significantly from the lifespan of female Ch. rufifacies. Wild Ch. rufifacies maggots were collected and allowed to pupate. After emergence, the adults were sexed and the number of days the adults lived were recorded. The resulting data was analyzed using a T-test in the SPSS statistics program. Results showed males to have a significantly longer lifespan than females. Keywords: Chrysomya rufifacies, Calliphoridae, forensic entomology, longevity, sex The activity of insects is of value during Using this calculation, they can then forensic investigations. Blow flies (Diptera: determine a time of death. Calliphoridae) are often among the first species to colonize a carcass. They play a Along with mPMI, blow flies can aid in major role in the process of decomposition. determining the locations of trauma on a Female blow flies oviposit on a suitable body. Because blow flies feed on injured recently-dead carcass in soft tissues such as tissue, fly larvae are seen at sites of pooled the eyes and mouth, in areas of moisture, in blood and sizable tissue openings, indicating open wounds, and in pooling blood (Johansen injury (Johansen et al 2014). -

1 I. Heat Production in Maggot Masses Formed by Forensically Important

I. Heat production in maggot masses formed by forensically important flies II. Abstract Death of a terrestrial vertebrate animal triggers intense competition among insects for use of the resource. A criminal investigator can use information on the type and timing of insects on a body to estimate the time since death (or post mortem interval) of the corpse. Fly larvae are the most useful insects for forensic investigations because they have relatively predictable development times. However, one major complicating factor is that these flies form large feeding masses on a corpse that can generate an enormous amount of heat. In fact, heat generation has been shown to exceed ambient environmental temperatures by as much as 30- 50oC, consequently altering fly development and well as subsequent determination of time of death. Surprisingly, no detailed studies have focused on determining the sources of heat production in a maggot mass, an important piece of information needed when attempting to calculate a post mortem interval. This summer I will explore heat production in fly maggot masses by testing the hypothesis that internal heat of a maggot mass is produced by feeding flies in maggot masses. I will also examine whether oxygen consumption rates in these fly larvae are an indicator of heat production. 1 III. Project Description (WC 1497) Many species of flies are attracted to human bodies almost immediately following death. These flies lay eggs or deposit young larvae on the corpse, which then subsequently feed directly on the tissues and fluids of the deceased. By understanding the succession patterns, geographical distribution, food preferences, development, and behavior of flies specific to a cadaver, the insects can be used as forensic tools for determining the time since death or post mortem interval (PMI).