Panel 2: the Post-Bubble World Has Profitability Been Achieved for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Ownership Chart

In 1983, 50 corporations controlled the vast majority of all news media in the U.S. At the time, Ben Bagdikian was called "alarmist" for pointing this out in his book, The Media Monopoly . In his 4th edition, published in 1992, he wrote "in the U.S., fewer than two dozen of these extraordinary creatures own and operate 90% of the mass media" -- controlling almost all of America's newspapers, magazines, TV and radio stations, books, records, movies, videos, wire services and photo agencies. He predicted then that eventually this number would fall to about half a dozen companies. This was greeted with skepticism at the time. When the 6th edition of The Media Monopoly was published in 2000, the number had fallen to six. Since then, there have been more mergers and the scope has expanded to include new media like the Internet market. More than 1 in 4 Internet users in the U.S. now log in with AOL Time-Warner, the world's largest media corporation. In 2004, Bagdikian's revised and expanded book, The New Media Monopoly , shows that only 5 huge corporations -- Time Warner, Disney, Murdoch's News Corporation, Bertelsmann of Germany, and Viacom (formerly CBS) -- now control most of the media industry in the U.S. General Electric's NBC is a close sixth. Who Controls the Media? Parent General Electric Time Warner The Walt Viacom News Company Disney Co. Corporation $100.5 billion $26.8 billion $18.9 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues $23 billion 1998 revenues $13 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues Background GE/NBC's ranks No. -

Gabriel Mann

GABRIEL MANN FEATURE FILMS HUMOR ME Danielle Renfrew Behrens, Ruth Pomerance, Emily Blavatnik, Fugitive Films Courtney Potts. Jamie Gordon, prods. Sam Hoffman, dir. TELEVISION SERIES THE MAYOR Jeremy Bronson, Dylan Clark, Daveed Diggs, Scott Stuber, ABC Jamie Tarses, exec prods. Score & Theme Jeremy Bronson, showrunner James Griffiths, dir. ROSEWOOD Marty Bowen, Wyck Godfrey, Todd Harthan, exec. prods. FBC / 20th Century Fox TV Todd Harthan, showrunner Score & Theme Richard Shepard, dir. RECTIFY Melissa Bernstein, Ray McKinnon, Mark Johnson, exec. prods. Sundance Channel / Gran Via Productions Ray McKinnon, showrunner Score Keith Gordon, dir. MODERN FAMILY Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, exec. prods. ABC/ 20th Century Fox Television Jason Winer/Reggie Hudlin, dir. Score 3 CABALLEROS Sarah Finn, dir. Disney Online Co-Score ANGEL FROM HELL Tad Quill, exec. prod. CBS / CBS TV Studios Tad Quill, showrunner Score Don Scardino, dir. DR. KEN Jared Stern, John Davis, John Fox, ABC / Sony Pictures TV Mike Sikowitz, exec. prods. Score Mike Sikowitz, showrunner Scott Ellis, dir. SCHOOL OF ROCK Richard Linklater, Scott Rudin, Jim Armogida, Steve Nickelodeon / Paramount TV Armogida, exec. prods. Score THE CROODS Netflix / Dreamworks Animation Score THE KICKS Elizabeth Allen Rosenbaum, prod /dir. Amazon Studios / Picrow Prods Andrew Orenstein, showrunner Score THE MCCARTHYS Will Gluck, Brian Gallivan, Mike Sikowitz, exec. prods. CBS / Sony Pictures TV Mike Sikowitz, showrunner Score Andy Ackerman, dir. The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 GABRIEL MANN MARRY ME David Caspe, Seth Gordon, Jamie Tarses, exec. prod. NBC / Sony Pictures TV David Caspe, showrunners Score Seth Gordon, dir. FRIENDS WITH BETTER LIVES Aaron Kaplan, exec. prod. CBS / 20th Century Fox Television Dana Klein, David Hemingson, showrunners Score & Theme TROPHY WIFE Lee Eisenberg, Emily Halpern, Sarah Haskins, exec. -

“The CBS Dream Team, It's Epic!” Adds Two New Series to Its Saturday

“THE CBS DREAM TEAM, IT’S EPIC!” ADDS TWO NEW SERIES TO ITS SATURDAY MORNING LINEUP, WHEN THE THIRD SEASON PREMIERES OCT. 3 “The Inspectors,” an Original Scripted Dramatic Series, and "Chicken Soup for the Soul's Hidden Heroes," Hosted By Brooke Burke-Charvet, Join the Three Hour Saturday Morning Block CBS announced today that two new series, THE INSPECTORS and CHICKEN SOUP FOR THE SOUL'S HIDDEN HEROES, will join THE CBS DREAM TEAM, IT’S EPIC! three- hour Saturday morning block when it returns for its third season Saturday, Oct. 3 (9:00 AM- 12:00 PM, ET/PT), on the CBS Television Network. The CBS DREAM TEAM Saturday morning line up is a diverse, family friendly schedule featuring compelling shows and stories of hope and compassion designed to enlighten, teach and inspire viewers to make a greater commitment to themselves, their families and their communities. The block is FCC educational/informational compliant, targeted to 13- to 16-year- olds and appealing to all viewers. THE INSPECTORS is a new scripted dramatic series set in Washington, D.C., inspired by compelling real cases handled by the United States Postal Inspection Service. In the series, Preston Wainwright (Bret Green), a determined teen who is thriving after being paralyzed in a car accident, works as an intern assisting his U.S. Postal Inspector mom, Amanda (Jessica Lundy), to solve crimes that deal with everything from internet scams, identity and mail theft, to consumer fraud. THE INSPECTORS strives to educate young people about making the right choices in their daily lives, encourages open communication between teens and parents and includes positive messaging regarding living with disabilities, overcoming challenges, beating the odds and the power of perseverance. -

Gabriel Mann

GABRIEL MANN FEATURE FILMS HUMOR ME Danielle Renfrew Behrens, Ruth Pomerance, Emily Blavatnik, Fugitive Films Courtney Potts. Jamie Gordon, prods. Sam Hoffman, dir. TELEVISION SERIES ROSEWOOD Marty Bowen, Wyck Godfrey, Todd Harthan, exec. prods. FBC / 20 th Century Fox TV Todd Harthan, showrunner Score & Theme Richard Shepard, dir. RECTIFY Melissa Bernstein, Ray McKinnon, Mark Johnson, exec. prods. Sundance Channel / Gran Via Productions Ray McKinnon, showrunner Score Keith Gordon, dir. MODERN FAMILY Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, exec. prods. ABC/ 20 th Century Fox Television Jason Winer/Reggie Hudlin, dir. Score ANGEL FROM HELL Tad Quill, exec. prod. CBS / CBS TV Studios Tad Quill, showrunner Score Don Scardino, dir. DR. KEN Jared Stern, John Davis, John Fox, ABC / Sony Pictures TV Mike Sikowitz, exec. prods. Score Mike Sikowitz, showrunner Scott Ellis, dir. SCHOOL OF ROCK Richard Linklater, Scott Rudin, Jim Armogida, Steve Nickelodeon / Paramount TV Armogida, exec. prods. Score THE CROODS Netflix / Dreamworks Animation Score THE KICKS Elizabeth Allen Rosenbaum, prod /dir. Amazon Studios / Picrow Prods Andrew Orenstein, showrunner Score THE MCCARTHYS Will Gluck, Brian Gallivan, Mike Sikowitz, exec. prods. CBS / Sony Pictures TV Mike Sikowitz, showrunner Score Andy Ackerman, dir. MARRY ME David Caspe, Seth Gordon, Jamie Tarses, exec. prod. NBC / Sony Pictures TV David Caspe, showrunners Score Seth Gordon, dir. FRIENDS WITH BETTER LIVES Aaron Kaplan, exec. prod. CBS / 20 th Century Fox Television Dana Klein, David Hemingson, showrunners Score & Theme The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 GABRIEL MANN TROPHY WIFE Lee Eisenberg, Emily Halpern, Sarah Haskins, exec. prods. ABC Lee Eisenberg, Gene Stupnitsky, showrunners Score STAR-CROSSED Josh Appelbaum, Andre Nemec, Scott Rosenberg, Richard CW / CBS Television Studios Shepard, Sean Furst, Bryan Furst, Meredith Averill, Daniel Score Gutman, exec. -

All Full-Power Television Stations by Dma, Indicating Those Terminating Analog Service Before Or on February 17, 2009

ALL FULL-POWER TELEVISION STATIONS BY DMA, INDICATING THOSE TERMINATING ANALOG SERVICE BEFORE OR ON FEBRUARY 17, 2009. (As of 2/20/09) NITE HARD NITE LITE SHIP PRE ON DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LITE PLUS WVR 2/17 2/17 LICENSEE ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX NBC KRBC-TV MISSION BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX CBS KTAB-TV NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX FOX KXVA X SAGE BROADCASTING CORPORATION ABILENE-SWEETWATER SNYDER TX N/A KPCB X PRIME TIME CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING, INC ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (DIGITALKTXS-TV ONLY) BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. ALBANY ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC ALBANY ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC ALBANY CORDELE GA IND WSST-TV SUNBELT-SOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS LTD ALBANY DAWSON GA PBS WACS-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY PELHAM GA PBS WABW-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY VALDOSTA GA CBS WSWG X GRAY TELEVISION LICENSEE, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY AMSTERDAM NY N/A WYPX PAXSON ALBANY LICENSE, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY PBS WMHT WMHT EDUCATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. -

New Audio Technology

New Audio Technology An Early Experience With 'Artist Experience' by Paul Shulins on 11.20.2012 inShare print rss ShareThis As HD Radio continues to improve, more and more features are added to the data set that is broadcast. In addition to HD1, HD2, Program Associated Data (artist, title and genre) and traffic services, a service called Artist Experience has been added by iBiquity Digital. It allows broadcasters to embed album art, station logos and other graphic content into the digital bit stream in real time for the purpose of being displayed on compatible receivers. During commercials, it is possible to broadcast images from sponsors, for example show the Coke logo during a Coke spot, and sell this as a value-added service. Additionally between songs or during public service shows, the radio station logo can be shown. There is a way to transmit this logo to the radio asynchronously to be held in non-volatile ram for immediate and frequent display when needed. Custom messaging is also possible to do though the use of the PSDGENTX, a software developer kit published by iBiquity. Using this I have successfully broadcast images of our FM talk personalities during the times they were on the air since there is no album art to broadcast on a talk station. Other information such as weather and financial data can be sent as well. HD Radio offers a whole range of new options for broadcasters, and some of those options have not even been thought of yet. As we strive to compete more effectively with other digital media, AE is just another tool we have available to us to provide a more rich experience to our listeners. -

CBS CORPORATION (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, DC 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of report (Date of earliest event reported): May 23, 2006 CBS CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 001-09553 04-2949533 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation) (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer Identification Number) 51 West 52nd Street, New York, New York 10019 (Address of principal executive offices) (zip code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (212) 975-4321 Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions (see General Instruction A.2. below): Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d- 2(b)) Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e- 4(c)) Section 8 Other Events Item 8.01 Other Events. On May 23, 2006, CBS Corporation (the ‘‘Company’’) announced that it will explore the divestiture of its radio stations in ten markets: Austin, Buffalo, Cincinnati, Columbus, Fresno, Greensboro-Winston/Salem, Kansas City, Memphis, Rochester and San Antonio. The Company has previously stated its intent to sell certain smaller market stations in order to maximize performance of the radio division overall. -

The Cbs Dream Team, It's Epic!

July 29, 2016 “THE CBS DREAM TEAM, IT’S EPIC!” ADDS NEW SERIES TO ITS SATURDAY MORNING LINEUP, WHEN THE FOURTH SEASON PREMIERES, OCT. 1 “The Open Road with Dr. Chris” Joins the Three-Hour Saturday Morning Block CBS announced today that a new series, THE OPEN ROAD WITH DR. CHRIS, will join THE CBS DREAM TEAM, IT’S EPIC! three-hour Saturday morning block when it returns for its fourth season, Saturday, Oct. 1 (9:00 AM-12:00 PM, ET/PT), on the CBS Television Network. The CBS DREAM TEAM Saturday morning line up is a diverse, family friendly schedule featuring compelling shows and stories of hope and compassion designed to enlighten, teach and inspire viewers to make a greater commitment to themselves, their families and their communities. The block is FCC educational/informational compliant, targeted to 13- to 16-year- olds and appealing to all viewers. THE OPEN ROAD WITH DR. CHRIS is hosted by renowned veterinarian Dr. Chris Brown, who also hosts DR. CHRIS PET VET. Complimenting Dr. Chris’ dedication to animal care and environmental stewardship, he embarks on an extraordinary journey around the globe, introducing young people to exhilarating experiences, from hiking in the heart of a volcano to swimming with humpback whales. Each episode will feature Dr. Chris in a culturally diverse destination where he will uncover the best- kept secret of the region. Whether he’s exploring the history of the Chilean capital or coming face-to-face with a live volcano in Vanuatu, THE OPEN ROAD WITH DR. CHRIS is the viewer’s passport to a rare educational adventure. -

The Big 6 Entertainment Corporations

THE BIG 6 ENTERTAINMENT CORPORATIONS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ News Corporation (abbreviated to News Corp) (NYSE: NWS) is one of the world's largest media conglomerates. Its chief executive officer is Rupert Murdoch, an influential and controversial media tycoon. News Corporation is a public company listed on the New York Stock Exchange and as a secondary listing on the London Stock Exchange (LSE: NCRA). Formerly incorporated in Adelaide, Australia, the company was re- incorporated in the United States state of Delaware after a majority of shareholders approved the move on 12 November 2004. The company is still listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX: NWS). News Corporation's United States headquarters is on Sixth Avenue (Avenue of the Americas) in New York City, in the 1960s-1970s portion of the Rockefeller Center complex. Revenue for the year ended 30 June 2005 was $23.859 billion. This does not include News Corporation's share of the revenue of businesses in which it owns a minority stake, which include two of its most important assets, DirecTV and BSkyB. Almost 70% of the company's sales come from its US businesses. Holdings: Film/TV Production and Distribution 20th Century Fox 20th Century Fox Home 20th Century Fox TV Fox Filmed Entertainment Fox 2000 Blue Sky Studios Fox Searchlight Pictures Fox Animation Studios(defunct) Fox Family World Wide Fox Sports Fox News IGN Entertainment Inc New World Communications Direct TV News Papers/Magazines/Publishers (select) New York Post The Times(Eng) The Sun (Eng) HarperCollins Ecco Press Perennial The Weekly Standard TV Guide Radio/Multimedia (select) Sky Radio Fox Sports Radio News American The Street.com Line One Orbis ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ The Walt Disney Company (most commonly known as Disney) (NYSE: DIS) is one of the largest media and entertainment corporations in the world. -

The Mark of Television Experience

1962-63 EDITION Including Contour Maps of of Commercial Stations as elevision Filed With The FCC.. Area Coverage and ARB Circulation USED BY THE ADVERTISINGoo AND TELEVISION INDUSTRIES at a HE AUTHORITATIVEact REFERENCE Glance... 1ForeignTV Stations & Sets Community Antenna Systems U.S. & Canada EquipmentMan- ifacturers Station Sales, Transfers, Brokers TV Networks Educational Stations Pro - Table of Contents 1ram Sources TV Set Makers IndustryStatistics TV Tape Producers FCC Personnel * Station Applications TV Color Stations Advertising Agencies Station Representatives Page 6-a PUBLISHED BY TELEVISION DIGEST, INC., WASHINGTON,D. C. $15.00 The Mark of Television Experience The" Who's Who" of Equipment Experts Broadcast Field Salo smen Atlanta 3, Ga. JA 4-7703 Cleveland 15, OhioCH 1-3450 Indianapolis, Ind. ME 6-5321 Portland 12, Ore. 234-7297 134 Peach Tree St., N.W. 1600 Keith Bldg. 501 N. LaSalle St. 1841 N.E. Couch St. P. G. Walters W. C. Wiseman D. Allen C. Raasch R. Smith Austin 3, Texas GL 3-8233 Dallas 35, Texas ME 1-3050 Kansas City 15, Mo. EM 1-6770 San Francisco 2, Cal. OR 3-8027 4605 Laurel Canyon Drive 7901 Carpenter Freeway 7711 State Line Rd. 420 Taylor St. J. N. Barclay E. H. Hoff D. Crawford E. E. Gloystein G. W. Bricker R. J. Newman Camden 2, N. J. WO 3-8000 Dedham, Mass. DA 6-8850 Memphis 12, Tenn. FA 4-4434 Seattle 4, Wash. MA 2-8350 Front & Cooper Sts. 336 Washington St. 3189 Summer Ave. 2250 First Ave., S. J. Gimbel J. R. Sims J. P. Ulasewicz B. -

CBS Television Stations and CBS Interactive Launch CBSN New York

CBS Television Stations and CBS Interactive Launch CBSN New York December 13, 2018 CBSN New York Is the First Major Local Market Streaming Service from CBS and Features Local News Content Produced by CBS 2 and WLNY 10/55 NEW YORK – Dec. 13, 2018 – CBS Television Stations and CBS Interactive today launched CBSN New York, the first of its planned 24/7 direct- to-consumer services that will stream anchored news coverage and live breaking news events from major markets served by CBS stations that are owned by CBS Corporation (NYSE: CBS.A and CBS). CBSN New York and the portfolio of CBSN Local services will build on the success of CBSN, the pioneering 24/7 streaming news service from CBS News and CBS Interactive that delivers live national and global news coverage and in-depth reporting from CBS News’ team of trusted journalists. CBSN New York is now available through CBSN on CBSNews.com and, beginning tonight, on the CBS News apps for mobile and connected TV devices. In addition, the service is now available through CBSNewYork.com and the CBS Local mobile app. CBSN, which launched in November 2014, continues to drive strong and sustained viewership growth. CBSN’s average monthly viewers have grown nearly 30% year-over-year in 2018, and the network set new viewership records in September, which is the top-ranked month in 2018 for total streams and the second-ranked month of all time, behind November 2016. Nearly 80% of CBSN’s viewers are between the ages of 18 and 49 with an average age of 38. -

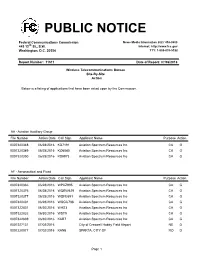

Public Notice

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission News Media Information 202 / 418-0500 445 12th St., S.W. Internet: http://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 Report Number: 11511 Date of Report: 07/06/2016 Wireless Telecommunications Bureau Site-By-Site Action Below is a listing of applications that have been acted upon by the Commission. AA - Aviation Auxiliary Group File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose Action 0007320348 06/28/2016 KD7191 Aviation Spectrum Resources Inc CA G 0007320349 06/28/2016 KO6045 Aviation Spectrum Resources Inc CA G 0007320350 06/28/2016 KS9973 Aviation Spectrum Resources Inc CA G AF - Aeronautical and Fixed File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose Action 0007320366 06/28/2016 WPXZ995 Aviation Spectrum Resources Inc CA G 0007320376 06/28/2016 WQBW629 Aviation Spectrum Resources Inc CA G 0007320377 06/28/2016 WQFE691 Aviation Spectrum Resources Inc CA G 0007320401 06/28/2016 WQGC788 Aviation Spectrum Resources Inc CA G 0007322831 06/30/2016 WHS3 Aviation Spectrum Resources Inc CA G 0007322832 06/30/2016 WST9 Aviation Spectrum Resources Inc CA G 0007322839 06/30/2016 KCB7 Aviation Spectrum Resources Inc CA G 0007227131 07/02/2016 City of Creswell Hobby Field AIrport NE D 0007220077 07/02/2016 KAN8 SPARTA, CITY OF RO D Page 1 AI - Aural Intercity Relay File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose Action 0007303280 06/30/2016 WMF485 COMMUNITY BROADCASTERS, LLC MD G AR - Aviation Radionavigation File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose