Possession and Dispossession in Property Law on Another Person’S Property (We Call It a Restrictive Covenant Or a Servitude)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 2007 Real Property Question 6

July 2007 Real Property Question 6 MEE Question 6 Owen owned vacant land (Whiteacre) in State B located 500 yards from a lake and bordered by vacant land owned by others. Owen, who lived 50 miles from Whiteacre, used Whiteacre for cutting firewood and for parking his car when he used the lake. Twenty years ago, Owen delivered to Abe a deed that read in its entirety: Owen hereby conveys to the grantee by a general warranty deed that parcel of vacant land in State B known as Whiteacre. Owen signed the deed immediately below the quoted language and his signature was notarized. The deed was never recorded. For the next eleven years, Abe seasonally planted vegetables on Whiteacre, cut timber on it, parked vehicles there when he and his family used the nearby lake for recreation, and gave permission to friends to park their cars and recreational vehicles there. He also paid the real property taxes due on the land, although the tax bills were actually sent to Owen because title had not been registered in Abe’s name on the assessor’s books. Abe did not build any structure on Whiteacre, fence it, or post no-trespassing signs. Nine years ago, Abe moved to State C. Since that time, he has neither used Whiteacre nor given others permission to use Whiteacre, and to all outward appearances the land has appeared unoccupied. Last year, Owen died intestate leaving his daughter, Doris, as his sole heir. After Owen’s death, Doris conveyed Whiteacre by a valid deed to Buyer, who paid fair market value for Whiteacre. -

Chapter 2– Property Ownership

Chapter 2– Property Ownership Learning Goals: • Define and describe land, real estate, and real property. • Identify and explain the concept of the bundle of legal rights in the ownership of real property. • Define and describe surface rights, subsurface rights, and air rights. • Describe the differences between real property and personal property. • Define and describe the differences between a fixture and a trade fixture. • Identify and apply the legal tests of a fixture. • List and explain the economic and physical characteristics of real property. Chapter 2 VOCABULARY Characteristics of Real Property include: A. Physical characteristics 1. Immobility—the land can be changed, but it cannot be moved 2. Indestructibility—the land can be changed, but it cannot be destroyed 3. Nonhomogeneity—all parcels of land are unique B. Economic characteristics 1. Relative scarcity—land in the imme diate areas may be limited or unavailable 2. Improvements—one property can affect the uses and values of many properties 3. Permanence of investment—real estate investments tend to be long-term and relatively stable 4. Area preference (situs)—refers to people’s preferences and choices in an area C. Real estate characteristics define land use 1. Contour and elevation of the parcel 2. Prevailing winds 3. Transportation 4. Public improvements 5. Availability of natural resources, such as minerals and water ABC Real Estate School 3st ed National Workbook August 2010 Page 19 Land: the surface of the earth plus the subsurface rights, extending downward to the center of the earth and upward infinitely into space; including things permanently attached by nature - such as trees and water. -

Property @Ction

December 2010 Review Property @ction Welcome to the Sixth Edition of the Quarterly Review from Hammonds’ Property@ction Team. In this issue we will look at the following: (i) You can’t take it with you! - when a chattel becomes a fixture; (ii) Authorised Guarantee Agreements – Guarantors; (iii) When is an excluded lease not excluded?; (iv) Rent as an administration expense; (v) A Strategic Approach to LPA Receiverships; We welcome all contributions to this review and if you would like to discuss this further please contact any of the editorial team. ‘You can’t take it with you!’ Whether you are a tenant or a freehold owner, you may think that whatever you put into a property remains yours to take away again when you leave. However, this is not always the case. Once an item is placed within a property it can become a “fixture”, deemed to belong to whoever owns the property. Fixtures will (unless specifically excluded by contract) be covered by a mortgage of the property, be included in a sale of the property and may pass to the landlord of a leasehold property on expiry or transfer of the lease. HOW DOES AN ITEM BECOME A FIXTURE? 1. Is there a sufficient degree of annexation? If the item rests on its own weight, then unless there is a demonstrable intention to use it as a fixture (see below) it will remain a “chattel” – the personal property of the person who bought the item and not of the landowner. This is the case regardless of the size of the item. -

Ownership – Acquisition, Proof and Extinction

Ownership Acquisition of ownership Modalities of Acquisition of Individual Ownership . Generally, the law recognizes two types/class of acquiring ownership: Original acquisition, and Derivative acquisition . Ownership is said to be acquired through original acquisition when an individual acquires ownership over a given thing by his own, without depending on anyone's title/ownership. Ownership may be acquires in this manner over a thing which: - has never been owned, res nullius - has had owner but abandoned, res derelictae - has owner, but the new owner doesn’t depend on the pre-existing OP as a source . Derivative acquisition refers to the acquisition of ownership through transfer of ownership. This is a case of buying/taking the right rather than establishing original ownership. It is a derivative mechanism of acquiring ownership. It requires juridical acts and is dependent on the quality of ownership of the original acquirer. Original Acquisition of Ownership . The CC recognizes 4 modes of original acquisition of OP: - Occupation - Possession in good faith - Usucaption - Accession . Some apply to acquisition of OP only on corporeal movables, others to immovable only & some for both. Acquisition of OP by Occupation . No clear definition of the term in the CC . From a systematic reading of Art 1151 we can describe Occupation as: a mode of acquiring OP whereby a person becomes an owner of a masterless corporeal chattel by taking possession of the thing with the intention of becoming owner. Thus, in order to become owner by occupation, the following elements must be fulfilled cumulatively: - The thing must be a corporeal movable - The thing must be susceptible of private appropriation - The thing must be masterless - The person must have taken possession of the thing - The possession must be with intention of becoming owner of the thing. -

The Uneasy Case for Adverse Possession

Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 2001 The Uneasy Case for Adverse Possession Jeffrey E. Stake Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Stake, Jeffrey E., "The Uneasy Case for Adverse Possession" (2001). Articles by Maurer Faculty. 221. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/221 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE The Uneasy Case for Adverse Possession JEFFREY EVANS STAKE* "[M]an, like a tree in the cleft of a rock, gradually shapes his roots to his surroundings, and when the roots have grown to a certain size, can't be displaced without cutting at his life. "1 INTRODUCTION In the above quotation, Justice Holmes explained title by prescription and the '2 "strange and wonderful" doctrine of adverse possession. Judge Posner has argued that Holmes was making a point about the diminishing marginal utility of income. I think not. One purpose of this Article is to develop a different interpretation of Justice Holmes, an interpretation with roots in modem experi- mental psychology and the theory of loss aversion. 4 Professors Stoebuck and Whitman stated in their property treatise, "If we had no doctrine of adverse possession, we should have to invent something very like it."'5 That was true in the past and may still be true today, but it is not at all clear that it will remain true in the future. -

Possession As the Root of Title

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1979 Possession as the Root of Title Richard A. Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard A. Epstein, "Possession as the Root of Title," 13 Georgia Law Review 1221 (1979). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POSSESSION AS THE ROOT OF TITLE Richard A. Epstein* I. TM PROBLEM STATED A beautiful sea shell is washed ashore after a storm. A man picks it up and puts it in his pocket. A second man comes along and takes it away from him by force. The first man sues to recover the shell, and he is met with the argument that he never owned it at all. How does the legal system respond to this claim? How should it respond? The same man finds the same shell, only now the state, through its public processes, comes along and insists that the shell belongs to the common fund. It offers the man nothing for it, claiming that the shell was found by luck and coincidence and not by planned and systematic labor. How does the legal system respond to this claim? How should it respond? The questions just put can recur in a thousand different forms in any organized legal system. The system itself presupposes that there are rights over given things that are vested in certain indi- viduals within that system. -

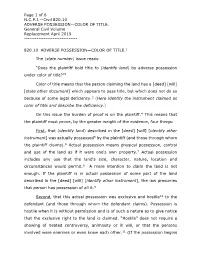

Page 1 of 6 N.C.P.I.—Civil 820.10 ADVERSE POSSESSION—COLOR of TITLE

Page 1 of 6 N.C.P.I.—Civil 820.10 ADVERSE POSSESSION—COLOR OF TITLE. General Civil Volume Replacement April 2019 ------------------------------ 820.10 ADVERSE POSSESSION—COLOR OF TITLE.1 The (state number) issue reads: “Does the plaintiff hold title to (identify land) by adverse possession under color of title?”2 Color of title means that the person claiming the land has a [deed] [will] [state other document] which appears to pass title, but which does not do so because of some legal deficiency.3 (Here identify the instrument claimed as color of title and describe the deficiency.) On this issue the burden of proof is on the plaintiff.4 This means that the plaintiff must prove, by the greater weight of the evidence, four things: First, that (identify land) described in the [deed] [will] [identify other instrument] was actually possessed5 by the plaintiff (and those through whom the plaintiff claims).6 Actual possession means physical possession, control and use of the land as if it were one's own property.7 Actual possession includes any use that the land's size, character, nature, location and circumstances would permit.8 A mere intention to claim the land is not enough. If the plaintiff is in actual possession of some part of the land described in the [deed] [will] [identify other instrument], the law presumes that person has possession of all it.9 Second, that this actual possession was exclusive and hostile10 to the defendant (and those through whom the defendant claims). Possession is hostile when it is without permission and is of such a nature as to give notice that the exclusive right to the land is claimed. -

QUESTION 1 Purchaser Acquired Blackacre from Seller in 1988

QUESTION 1 Purchaser acquired Blackacre from Seller in 1988. Seller had purchased the property in 1978. Throughout Seller's ownership, Blackacre had been described by a metes and bounds legal description, which Seller believed to include an island within a stream. Seller conveyed title to Blackacre to Purchaser through a special warranty deed describing Blackacre with the same legal description through which Seller acquired it. At all times while Seller owned Blackacre, she thought she owned the island. In 1978, she built a foot bridge to the island to allow her to drive a tractor mower on it. During the summer, she regularly mowed the grass and maintained a picnic table on the island. Upon acquiring Blackacre, Purchaser continued to mow the grass and maintain the picnic table during the summer. In 1994, Neighbor, who owns the property adjacent to Blackacre, had a survey done of his property (the accuracy of which is not disputed) which shows that he owns the island. In 1998, Neighbor demanded that Purchaser remove the picnic table and stop trespassing on the island. QUESTION: Discuss any claims which Purchaser might assert to establish his right to the island or which he may have against Seller. DISCUSSION FOR QUESTION 1 I. Mr. Plaintiffs Claims versus Mr. Neighbor One who maintains continuous, exclusive, open, and adverse possession of real property for the requisite statutory period may obtain title thereto under the principle of adverse possession. Edie v. Coleman, 235 Mo. App. 1289, 141 S.W. 2d 238 (1940), Vade v. Sickler, 118 Colo. 236, 195 P.2d 390 (1948). -

Acquisition by Adverse Possession Why Does the Law Provide for Forced

Acquisition by Adverse Possession Transfer of interest in land without the consent of the prior owner and even in spite of the dissent of such owner. A forced conveyance. U N I V E R S I T Y of H O U S T O N Professor Marcilynn A. Burke Copyright©2013 Marcilynn A. Burke All rights reserved. Provided for student use only. Why does the law provide for forced conveyances through AP? • Efficient allocation • Reliance interest of 3d parties • Reliance interest of AP U N I V E R S I T Y of H O U S T O N Professor Marcilynn A. Burke Copyright©2013 Marcilynn A. Burke All rights reserved. Provided for student use only. 1 Why does the law provide for forced conveyances through AP Cont’d? • Desirability of quieting title • Decay or loss of evidence • Interest in discouraging sleeping owners U N I V E R S I T Y of H O U S T O N Professor Marcilynn A. Burke Copyright©2013 Marcilynn A. Burke All rights reserved. Provided for student use only. Van Valkenburgh v. Lutz, 106 N.E. 2d 28 (N.Y. 1952) Casebook, p. 122 1916 Lutz starts truck 1928 1937 1912 farm on lot 19 Lutz loses job and Joseph & Marion Mary & William Lutz starts to tend garden Van Valkenburgh buy lots 14 & 15 and 1920 buy lots west of Lot 19 travel across lots 19-22 Charlie’s one-room house on lot 19 1946 April 1947 July 6, 1947 Feud begins between Lutzes Van Valkenburghs Van Valkenburghs and Van Valkenburghs over buy lots 19-22 take possession of lot 19 children in Lutzes’ garden July 21, 1947 July 8, 1947 August (?) 1947 Jan. -

FEOFFMENT (Fef´-Ment). an Early Mode of FICTITIOUS PAYEE (Fick-Tish´-Us Pay-Ee´)

FEOFFMENT (fef´-ment). An early mode of FICTITIOUS PAYEE (fick-tish´-us pay-ee´). Any conveyance, by which the possession of a designation of a payee in a negotiable instrument freehold estate was transferred by the technical who is non-existent or who was not intended ceremony of livery of seisin. to receive the instrument in the first place. The instrument in such case is considered as payable FEOFFMENT TO USE (fef´-ment to uze). The to bearer. feoffment or transfer of lands to a person for the benefit of another. FIDUCIARY (fi-du´-shi-ar-re). Relating to or founded upon a trust or confidence. A trustee or FEOFFER (fef-or´). The person who makes a one who holds a thing in trust for another. feoffment. FIEF (feef). A fee, feud, or inheritable estate. FERAE NATURAE (fee´-ree na-tu´-ree). Untamed; animals in their wild state or regarded as FIERI FACIAS (fy´-e-ry fay´-she-as). (Abbreviated unclaimed for ownership. as fi. fa.) In Latin the meaning is that you cause to be made. A writ of execution directing the sheriff FEUD (fude). A fee; a hereditary right to use lands, to levy upon the goods and chattels of a debtor to payment for which was rendered in services to satisfy a judgment. the lord, with ownership of the land retained by the lord. FILIUS (fil´-i-us). A son; a child. FEUDAL (fu´-dal). Pertaining or relating to the FIN (fin). End; limit; termination; expiration; feudal system, feudal law, or the form of land objective. tenure under which the land is held under a superior or lord. -

Adverse Possession Adolph Kanneberg

Marquette Law Review Volume 15 Article 1 Issue 3 April 1931 Adverse Possession Adolph Kanneberg Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Adolph Kanneberg, Adverse Possession, 15 Marq. L. Rev. 127 (1931). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol15/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW VOLUME XV APRIL, 1931 NO. THREE ADVERSE POSSESSION By ADOLPH KANNEBERG* T HERE is a familiar saying which has attained almost to the dignity of a proverb, to the effect that "possession is nine points of the law." No attempt has been made to determine the origin of this expression, but there is at least a strong possibility that it was coined at some stage of a dispute between a person claiming a record title to property and another claiming a title based on occupancy of the property. The expression itself would seem to indicate that there was some feeling that actual occupancy of property conferred certain pro- prietary rights which might prove a sounder basis for a title claim than a mere record of title without possession of the property. Under the old English common law, transfer of title to real prop- erty, or real estate as it is commonly known, was accomplished by a process known as "livery of seizin." The grantor of the title would act a fictitious delivery of the land itself by handing or delivering to the grantee a stick of wood, a handful of ground, a branch of a tree, or a stone taken from the land which was the subject of the con- veyance. -

Possession As the Origin of Property Carol M

Possession as the Origin of Property Carol M. Roset How do things come to be owned? This is a fundamental puz- zle for anyone who thinks about property. One buys things from other owners, to be sure, but how did the other owners get those things? Any chain of ownership or title must have a first link. Someone had to do something to anchor that link. The law tells us what steps we must follow to obtain ownership of things, but we need a theory that tells us why these steps should do the job. John Locke's view, once described as "the standard bourgeois theory,"1 is probably the one most familiar to American students. Locke argued that an original owner is one who mixes his or her labor with a thing and, by commingling that labor with the thing, establishes ownership of it.' This labor theory is appealing because it appears to rest on "desert,"3 but it has some problems. First, without a prior theory of ownership, it is not self-evident that one owns even the labor that is mixed with something else.4 Second, even if one does own the labor that one performs, the labor theory provides no guidance in determining the scope of the right that t Professor of Law, Northwestern University, and Visiting Professor of Law, University of Chicago. For comments and suggestions I especially thank the George Washington Uni- versity Property Colloquium, to which a version of this paper was given in March 1983, and Mary Ann Glendon, Victor Goldberg, Thomas Grey, Thomas Merrill, Frank Michelman, Phyllis Palmer, Daniel Polsby, and Rayman Solomon.