Adverse Possession Adolph Kanneberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIFORM REAL PROPERTY ELECTRONIC RECORDING ACT (Last Revised Or Amended in 2005)

UNIFORM REAL PROPERTY ELECTRONIC RECORDING ACT (Last Revised or Amended in 2005) drafted by the NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS and by it APPROVED AND RECOMMENDED FOR ENACTMENT IN ALL THE STATES at its ANNUAL CONFERENCE MEETING IN ITS ONE-HUNDRED-AND-THIRTEENTH YEAR PORTLAND, OREGON JULY 30-AUGUST 6, 2004 WITH PREFATORY NOTE AND COMMENTS Copyright ©2004 By NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS April 2005 ABOUT NCCUSL The National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL), now in its 114th year, provides states with non-partisan, well-conceived and well-drafted legislation that brings clarity and stability to critical areas of state statutory law. Conference members must be lawyers, qualified to practice law. They are practicing lawyers, judges, legislators and legislative staff and law professors, who have been appointed by state governments as well as the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to research, draft and promote enactment of uniform state laws in areas of state law where uniformity is desirable and practical. • NCCUSL strengthens the federal system by providing rules and procedures that are consistent from state to state but that also reflect the diverse experience of the states. • NCCUSL statutes are representative of state experience, because the organization is made up of representatives from each state, appointed by state government. • NCCUSL keeps state law up-to-date by addressing important and timely legal issues. • NCCUSL’s efforts reduce the need for individuals and businesses to deal with different laws as they move and do business in different states. -

Deed Recording

DEED RECORDING Deeds are important legal documents. The Onondaga County Clerk’s Office strongly recommends consulting an attorney regarding the preparation and filing/recording of any legal document. OUR OFFICE IS PROHIBITED BY LAW FROM PROVIDING ANY LEGAL ADVCE. THE ACCEPTANCE OF AN INSTRUMENT FOR RECORDING IN NO WAY IMPLIES AN ENDORSEMENT OR LEGAL SUFFICIENCY OR A GUARANTEE OF TITLE. IF YOU CHOOSE TO ACT AS YOUR OWN ATTORNEY YOU ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR LEGAL COMPLIANCE AND ANY IMPLICATIONS THEREOF. To find a local attorney who specializes in real estate, contact the Onondaga County Bar Association Lawyer Referral Serve at 315.471.2690. Their website is located at https://www.onbar.org/ Our office does not supply forms. To purchase a New York State specific deed form, you may visit the Blumberg Legal Forms website at: https://www.blumberg.com/forms/ All deed filings must be accompanied by both an RP-5217 and TP 584 All recording in Onondaga County require a legal description for the subject property. ADDITIONAL RECORDING FEE EFFECTIVE MARCH 11, 2020 Effective March 11, 2020 there will be a $10 fee added to all residential deed recordings. On January 11, 2020 Governor Cuomo signed into law an amendment to Real Property Law Section 291 that requires County Clerks to notify the owner(s) of record of residential real property when a document is recorded affecting said residential property. The law also allows a reasonable fee to be assessed for said notices. The NYS Association of County Clerks, in order to provide uniformity throughout NYS, has determined that $10 is a reasonable fee per document. -

Title Matters Affecting Parties in Possession: By

TITLE MATTERS AFFECTING PARTIES IN POSSESSION: ADVERSE POSSESSION, AFTER-ACQUIRED TITLE, & THE RULE AGAINST PERPETUITIES BY DONALD G. SINEX SCOTT C. PETRY SUSAN A. STANTON TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 I. ADVERSE POSSESSION…….……………………………………………………………. 1 1. Adverse Possession………...………………...……………………………………….......... 2 2. Identifying Issues in Record Title…………………………………………………………. 3 a. Historical Changes in Metes and Bounds…………………………………………… 4 b. Adverse Possession of Minerals……………………………………………………… 4 c. Adverse Possession in Cotenancy, Landlord-Tenant, & Grantor-Grantee Situations………………………………………………………………………….…...... 5 d. Distinguishing Coholders from Cotenants………………………………………….. 6 3. Adverse Possession Requirement………………………………………………………… 7 4. Other Issues………………………………………...……………………………………….. 9 II. AFTER ACQUIRED TITLE………………………….…………………………………………. 10 1. The Doctrine………………..……... ……………………………………………………….. 10 2. Bases Used by Courts in Applying the Doctrine…………………………………........... 11 3. Conveyance Instruments that an Examiner is Likely to Encounter…………………… 12 a. Deeds of Trust and Liens……………………………………………………………... 12 b. Oil & Gas Leases and Limitations……………………………………………………. 14 c. Public Lands……………………………………………………………………………. 15 d. Title Acquired in Trust………………………………………………………………… 16 e. Quitclaims and Limitations…………………………………………………………… 16 4. Effect on Notice and Purchasers………………………………………………………….. 18 a. Subsequent Purchaser…………………………………………………………………. 19 b. Protections……………………………………...………………………………………. 19 c. Duty to Search…………………………………………………………………………. -

July 2007 Real Property Question 6

July 2007 Real Property Question 6 MEE Question 6 Owen owned vacant land (Whiteacre) in State B located 500 yards from a lake and bordered by vacant land owned by others. Owen, who lived 50 miles from Whiteacre, used Whiteacre for cutting firewood and for parking his car when he used the lake. Twenty years ago, Owen delivered to Abe a deed that read in its entirety: Owen hereby conveys to the grantee by a general warranty deed that parcel of vacant land in State B known as Whiteacre. Owen signed the deed immediately below the quoted language and his signature was notarized. The deed was never recorded. For the next eleven years, Abe seasonally planted vegetables on Whiteacre, cut timber on it, parked vehicles there when he and his family used the nearby lake for recreation, and gave permission to friends to park their cars and recreational vehicles there. He also paid the real property taxes due on the land, although the tax bills were actually sent to Owen because title had not been registered in Abe’s name on the assessor’s books. Abe did not build any structure on Whiteacre, fence it, or post no-trespassing signs. Nine years ago, Abe moved to State C. Since that time, he has neither used Whiteacre nor given others permission to use Whiteacre, and to all outward appearances the land has appeared unoccupied. Last year, Owen died intestate leaving his daughter, Doris, as his sole heir. After Owen’s death, Doris conveyed Whiteacre by a valid deed to Buyer, who paid fair market value for Whiteacre. -

Virginia Real Property Electronic Recording Standard

SEC505-00.1 Effective Date: May 1, 2007 December 8, 2016 COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA Information Technology Resource Management Standard VIRGINIA REAL PROPERTY ELECTRONIC RECORDING STANDARD Virginia Information Technologies Agency (VITA) i Virginia Real Property Electronic Recording Standard SEC505-00.1 Effective Date: May 1, 2007 December 8, 2016 PUBLICATION VERSION CONTROL ITRM Publication Version Control: It is the user's responsibility to ensure they have the latest version of the ITRM publication. Questions should be directed to the Associate Director Manager for Policy, Practice and Enterprise Architecture (PPA) (EA) at VITA’s Relationship Management Governance (RMG) Strategic Management Services (SMS). SMS EA will issue a Change Notice Alert, post it on the VITA Web site, and provide an email announcement to the Circuit Court Clerks, as well as other parties PPA EA considers to be interested in the change. This chart contains a history of this ITRM publication’s revisions. Version Date Purpose of Revision Original 05/01/2007 Base Document This administrative update is necessitated by changes in the Code of 00.1 12/08/2017 Virginia and organizational changes in VITA. No substantive changes were made to this document. ii Virginia Real Property Electronic Recording Standard SEC505-00.1 Effective Date: May 1, 2007 December 8, 2016 PREFACE real estate settlement process for the benefit of citizens of the Commonwealth and users of the electronic Publication Designation filing system. SEC505-00.1 Sections 55-66.3 through 55-66.5 and 55-66.8 through Subject 55-66.15: This Standard for the electronic acceptance and recordation for the release of mortgage, rescinding Virginia Real Property Electronic Recording Standard erroneously recorded certificates of satisfaction, requirements on secured creditors, and the form and Effective Date effect of satisfaction facilitates real estate transactions May 1, 2007 December 8, 2016 in the Commonwealth. -

Usufruct Study Guide

Article 562 ± 578 1. Define usufruct. Usufruct is a real right by virtue of which a person is given the right to enjoy the property of another with the obligation of preserving its form and substance, unless the title constituting it or the law provides otherwise. 2. What are the three fundamental Rights Appertaining to Ownership? Ownership consists of three fundamental rights, to wit: - jus disponende (right to dispose) - jus utendi (right to use) - jus fruendi (right to the fruits) 3. Of the above-mentioned fundamental rights, what consists usufruct and naked ownership? The combination of the jus utendi and jus fruendi is called usufruct. The remaining right jus disponendi is really the essence of what is termed ³naked ownership´. 4. What right is transferred to the usufructuary and what right is remained with the owner? In a usufruct, only the jus utendi and jus fruendi over the property is transferred to the usufructuary. The owner of the property maintains the jus disponendi or the power to alienate, encumber, transform, and even destroy the same. (Hemedes vs. CA, 316 SCRA 347 1999). 5. What are the formulae with respect to full ownership, usufruct, and naked ownership? The following are the formulae: - Full Ownership equals Naked Ownership plus Usufruct - Naked Ownership equals Full Ownership minus Usufruct - Usufruct equals Full Ownership minus Naked Ownership 6. What are the characteristics or elements of usufruct? The following are the characteristics or elements of usufruct: ESSENTIAL CHARACTERISTICS: those without which it can not be termed usufruct: (a) It is REAL RIGHT (whether registered in the Registry of Property or not). -

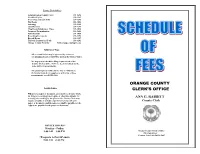

Schedule of Fees (PDF)

County Clerk Offices Administration/County Clerk 291-2690 Certified Copies 291-3287 Court Papers/Court Calls 291-3286 File Room 291-3086 Indexing 291-3285 Land Records 291-3287 Map Room/Subdivision Maps 291-3084 Passports/Naturalization 291-2698 Pistol Permits 291-3060 Recording Documents 291-3292 Record Room 291-3287 Uniform Commercial Code 291-3292 Orange County Web Site www.orangecountygov.com Subdivision Maps After a subdivision map is approved by a town or city planning board, it MUST be filed in the Clerk’s Office. We urge you to check the filing requirements of the County Clerk’s Office that have been mandated by the state and local governments. The planning board office in the city or town where the land is located can supply you with a list of these requirements, or call 291-3084. ORANGE COUNTY Legible Copies CLERK’S OFFICE Whenever a paper or document, presented to a County Clerk for filing or recording is not legible or otherwise suitable for ANN G. RABBITT scanning or recording by the process, the County Clerk may require a legible or suitable copy thereof along with such County Clerk paper or document, and the same fees shall be payable for the copy as are payable for the paper or document. OFFICE HOURS * Monday – Friday 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM Orange County Clerk’s Office 255 Main Street Goshen, New York 10924-1697 *Passports & Pistol Permits 9:00 AM – 4:30 PM ASSIGNMENT OF MORTGAGE*, To Record 45.00 MECHANICS LIEN, To File 15.00 Plus Per Page 5.00 Affidavit of Service (35 Days) 5.00 Plus Each Additional Mortgage 3.00 Discharge by Payment into Court 3.00 1st Asst. -

An Environmental Critique of Adverse Possession John G

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons McGeorge School of Law Scholarly Articles McGeorge School of Law Faculty Scholarship 1994 An Environmental Critique of Adverse Possession John G. Sprankling Pacific cGeM orge School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/facultyarticles Part of the Environmental Law Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation John G. Sprankling, An Environmental Critique of Adverse Possession, 79 Cornell L. Rev. 816 (1994) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the McGeorge School of Law Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in McGeorge School of Law Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cornell Law Review Volume 79 Article 2 Issue 4 May 1994 Environmental Critique of Adverse Possession John G. Sprankling Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation John G. Sprankling, Environmental Critique of Adverse Possession , 79 Cornell L. Rev. 816 (1994) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol79/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ENVIRONMENTAL CRITIQUE OF ADVERSE POSSESSION John G. Spranklingf INTRODUCTION Consider three applications of modem adverse possession law to wild, undeveloped land. -

Claim of Title in Adverse Possession

CLAIM OF TITLE IN ADVERSE POSSESSION HE RY WinnRop BALLArnNE University of Illinois I. BASIS AND EXTENT OF REQUIREMENT. The adverse possession which is requisite to establish title and bar the rights of the ousted owner must, it is said, include five elements. It must be (I) hostile or adverse, (2) actual (as to part of the land), (3) visible, notorious and exclusive, (4) continuous for the statutory period, and (5)under claim or color of title.' It is almost universally held that the basis of an adverse possession is a claim of title or right. No title can be acquired against the true owner by merely squatting on real estate.2 Color of title is not neces- sary, but the possession must evidence some claim inconsistent with that of the true owner. A few cases, however, seem to declare that claim of title is not essential s Why should "claim of title" be an essential element? In most statutes of limitation there is no mention of claim of title. By what authority, then, do courts superadd such a requirement? The explanation is that the title acquired under the statute results from the joint operation of the statute and the common law rules as to possession. The owner must be ousted and put to his action before the statute begins to run against him. The operation of the statute is sometimes called "negative prescription". There is no "statutory conveyance" to the man in possession. The statute deals with the remedies of the claimant out of possession. The remedies and title of the ousted owner are extinguished rather than transferred by the statute.4 1 Zirngibl v, Calumet Dock Co. -

Recording Deeds in Lake County

Recording Deeds in Lake County Deeds for properties located in Lake County should be recorded in the Lake County Recorder of Deeds Office. Deeds are accepted for recording in person or by mail. Once recorded, the document will be assigned a document number, scanned, and entered into a Grantor/Grantee index. The original document will be returned to the party named on the document. After recording, land records are available for public viewing. As always, it is suggested that you consult legal & accounting professionals to fully understand the legal & tax implications of recording any property deed changes. If there is anything that our staff can do to help make this process easier for you, please let us know. 18 N County St – 6th Floor Waukegan, IL 60085-4358 Phone: (847) 377-2575 Fax: (847) 984-5860 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lakecountyil.gov/recorder Recording Requirements: 1. Deeds must be dated, signed & notarized. 2. Parties involved must be named. 3. Grantee's (buyer) address must be listed. 4. Deeds require a complete legal description. 5. Metes & bounds legal descriptions require a Plat Act affidavit. 6. Deeds require the name & address of the Preparer. 7. Deeds require “Mail to” information (name & address) - this is where the recorded document must be returned, after it has been recorded. 8. Taxpayer name & address for tax bills must be listed. 9. All deeds require either a completed Illinois PTAX- 203 form or a signed & dated exemption statement. 10. Local municipal transfer tax stamps must be obtained at the local municipality prior to being submitted to the Recorder of Deeds Office. -

Chapter 2– Property Ownership

Chapter 2– Property Ownership Learning Goals: • Define and describe land, real estate, and real property. • Identify and explain the concept of the bundle of legal rights in the ownership of real property. • Define and describe surface rights, subsurface rights, and air rights. • Describe the differences between real property and personal property. • Define and describe the differences between a fixture and a trade fixture. • Identify and apply the legal tests of a fixture. • List and explain the economic and physical characteristics of real property. Chapter 2 VOCABULARY Characteristics of Real Property include: A. Physical characteristics 1. Immobility—the land can be changed, but it cannot be moved 2. Indestructibility—the land can be changed, but it cannot be destroyed 3. Nonhomogeneity—all parcels of land are unique B. Economic characteristics 1. Relative scarcity—land in the imme diate areas may be limited or unavailable 2. Improvements—one property can affect the uses and values of many properties 3. Permanence of investment—real estate investments tend to be long-term and relatively stable 4. Area preference (situs)—refers to people’s preferences and choices in an area C. Real estate characteristics define land use 1. Contour and elevation of the parcel 2. Prevailing winds 3. Transportation 4. Public improvements 5. Availability of natural resources, such as minerals and water ABC Real Estate School 3st ed National Workbook August 2010 Page 19 Land: the surface of the earth plus the subsurface rights, extending downward to the center of the earth and upward infinitely into space; including things permanently attached by nature - such as trees and water. -

Property @Ction

December 2010 Review Property @ction Welcome to the Sixth Edition of the Quarterly Review from Hammonds’ Property@ction Team. In this issue we will look at the following: (i) You can’t take it with you! - when a chattel becomes a fixture; (ii) Authorised Guarantee Agreements – Guarantors; (iii) When is an excluded lease not excluded?; (iv) Rent as an administration expense; (v) A Strategic Approach to LPA Receiverships; We welcome all contributions to this review and if you would like to discuss this further please contact any of the editorial team. ‘You can’t take it with you!’ Whether you are a tenant or a freehold owner, you may think that whatever you put into a property remains yours to take away again when you leave. However, this is not always the case. Once an item is placed within a property it can become a “fixture”, deemed to belong to whoever owns the property. Fixtures will (unless specifically excluded by contract) be covered by a mortgage of the property, be included in a sale of the property and may pass to the landlord of a leasehold property on expiry or transfer of the lease. HOW DOES AN ITEM BECOME A FIXTURE? 1. Is there a sufficient degree of annexation? If the item rests on its own weight, then unless there is a demonstrable intention to use it as a fixture (see below) it will remain a “chattel” – the personal property of the person who bought the item and not of the landowner. This is the case regardless of the size of the item.