A Measure of Change: Delineating the “Two Florida's” Adam Harpool

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kissimmee/Okeechobee Land Assessment Region: Kissimmee River

SFWMD Land Use Assessment 2013 Kissimmee River Rivers program acquired 49,000 acres in 290 land Polk, Osceola, Highlands, and Okeechobee Counties transactions to support the restoration of the river. Laboratory studies and field demonstrations were Area within planning boundary footprint conducted throughout the 1980s. A recommended plan ~ 116,317 acres was developed, and The Kissimmee River Restoration District fee-simple ownership and Project was authorized by Congress in the 1992 Water Right-of-Way fee interest Resources Development Act as a joint partnership between ~ 95,914 acres the District and the US Army Corps of Engineers. The Other public fee-simple ownership project was designed to restore over 40 square miles of ~ 1827 acres river/floodplain ecosystem including 43 miles of Area under other regulatory restriction meandering river channel and 27,000 acres of wetlands. To (conservation easement, platted preserve area, etc.) complete the restoration it was necessary to acquire ~ 1508 acres sufficient rights in the land within the 100-year floodplain. Site Overview Assessment Units Historically, the Kissimmee River meandered over 103 Pool A: KICCO and Blanket Bay miles within a one to two mile wide floodplain. The This area involved some of the earliest acquisitions for the floodplain, approximately 56 miles long, sloped gradually river. An early demonstration project to support the full to the south from an elevation of about 51 feet at Lake river restoration occurred over a portion of this site. Kissimmee to about 15 feet at Lake Okeechobee; falling an Kissimmee Prairie average of about 4 inches in elevation over each mile of The District acquired the parcels within the river the river. -

X X United Way of Central Florida

United Way of Central Florida PO Box 1357 Highland City, FL 33846-1357 863-648-1500 uwcf.org 1 My Personal Information UWCF respects the privacy of our donors & does not disclose personal information to third parties Prefix: Name: Co. Name: Home Address: Division/Emp. ID #: City: State: Zip: Work Phone: -- Cell Phone: -- Date of Birth: // Preferred Email: 2 My Giving (Select one) 4 My Recognition (Optional) Option #1 Pledge: Payroll Deduction PLEASE LIST MY NAME AS IT APPEARS IN SECTION ONE OR AS FOLLOWS: I pledge the following each pay period: Preferred Recognition Name $20 $10 $5 $3 Other: I prefer that my gift remain anonymous Please combine my gift with my spouse X = Spouse Name $ Pay Periods My total annual gift: $ Option #2 Pledge: One-Time Gift Spouse’s Employer Check (Payable to United Way of Central Florida) My gift of $1000 or more qualifies me as a LEADERSHIP GIVER Cash My total annual gift: $ I would like to participate in the Young Leader’s Step-Up program. Please check one: $250 $500 $750 $1,000 (Minimum gift of $20) Option #3 Pledge: Direct Bill I am interested in learning more about other Leadership Step-up programs. Please bill me in the amount of Bill beginning (MM/YY): One-time Monthly Quarterly My Designation (Optional) My total annual gift: $ 5 Option #1: Community Investment Option #4 Pledge: Credit Card or Stock Transfer* The Best Investment. These funds improve lives with a focus on education, income, health and safety net. Over 120 volunteers on 18 *For credit card transactions or stock transfers, please Community Investment Teams distribute contributions according to our contact the United Way office at 863-648-1500. -

X United Way of Central Florida

United Way of Central Florida PO Box 1357 Highland City, FL 33846-1357 863-648-1500 uwcf.org 1 My Personal Information UWCF respects the privacy of our donors & does not disclose personal information to third parties Prefix: Name: Co. Name: Home Address: Division/Emp. ID #: City: State: Zip: Work Phone: -- Cell Phone: -- Date of Birth: // Preferred Email: My Giving (Select one) 3 My Recognition (Optional) 2 PLEASE LIST MY NAME AS IT APPEARS IN SECTION ONE OR AS FOLLOWS: Option #1 Pledge: Payroll Deduction I pledge the following each pay period: Preferred Recognition Name $20 $10 $5 $3 Other: I prefer that my gift remain anonymous Please combine my gift with my spouse X = Spouse Name $ Pay Periods My total annual gift: $ Spouse’s Employer Option #2 Pledge: One-Time Gift My gift of $1000 or more qualifies me as a LEADERSHIP GIVER Check (Payable to United Way of Central Florida) I would like to participate in the Young Leader’s Step-Up program. Cash My total annual gift: $ Please check one: $250 $500 $750 $1,000 I am interested in learning more about other Leadership Step-up programs. Option #3 Pledge: Direct Bill (Minimum gift of $20) Please bill me in the amount of Bill beginning (MM/YY): My Designation (Optional) One-time Monthly Quarterly 4 Option #1: Community Investment My total annual gift: $ The Best Investment. These funds improve lives with a focus on education, income, health and safety net. Over 120 volunteers on 17 Community Investment Teams distribute contributions according to our Option #4 Pledge: Credit Card or Stock Transfer* community’s most critical needs. -

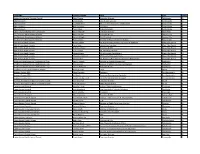

Membership List for Website 8-6-20

COMPANY CONTACT NAME TITLE CITY STATE Apalachee Regional Planning Council Chris Rietow Executive Director Tallahassee FL Babcock Ranch Erika Woods SVP of Legal Services Punta Gorda FL Babcock Ranch Lucienne Pears VP Economic & Business Development Punta Gorda FL Babcock Ranch Rick Severance President Punta Gorda FL Babcock Ranch Tyler Kitson Project Manager Punta Gorda FL Baker County Development Commission Darryl Register Executive Director Macclenny FL Bay Economic Development Alliance Becca Harden President & CEO Panama City FL Bay Economic Development Alliance Garrett Wright Vice President Panama City FL Bay Economic Development Alliance Polly Jackson Director of Finance & Administration Panama City FL BDB of Palm Beach County Brian Cartland VP Business Recruitment, Expansion & Retention West Palm Beach FL BDB of Palm Beach County Gary Hines Senior Vice President West Palm Beach FL BDB of Palm Beach County Kelly Smallridge President & CEO West Palm Beach FL BDB of Palm Beach County Luke Jackson VP, The Glades Region West Palm Beach FL BDB of Palm Beach County Shawn Rowan VP of Business Recruitment West Palm Beach FL BDB of Palm Beach County Shereena Coleman VP Business Existing Industry West Palm Beach FL BDB of Palm Beach County Tim Dougher VP, Businesss Recruitment, Retention & Expansion West Palm Beach FL Bradenton Area Economic Development Corp. Lauren Kratsch Director of Project Management Bradenton FL Bradenton Area Economic Development Corp. Max Stewart Director of Global Business Development Bradenton FL Bradenton Area Economic -

Enterprise Florida Annual Report FY 2011-2012 Photo: Nasaphoto

Enterprise Florida Annual Report FY 2011-2012 Photo: NASAPhoto: Enterprise Florida is the lead economic development organization for the state of Florida. Rick Scott, Governor Chairman, Enterprise Florida, Inc. “Florida is receiving a lot of attention from companies that want to move to our business-friendly climate as well as from current in-state companies desiring to expand here. The reason is that we’ve lowered business taxes and are eliminating regulations that restrict the ability to grow. Enterprise Florida works hard to capitalize on this interest. What also helps is that Florida’s economy is strengthening: unemployment is down, tourism is up, exports are up, home prices are up, home sales are up, and new home construction is up. My administration and Enterprise Florida look forward to bringing more job opportunities to all our citizens.” Howell W. Melton Vice Chairman, Enterprise Florida, Inc. “Creating jobs to get citizens back to work is one of the most important issues Florida faces. Enterprise Florida facilitated the creation of 25,339 jobs through competitive projects this past year, but we still have a lot of work to do. The more jobs we create, there’s less dependence on state services, private investment flourishes, entrepreneurship expedites and the state’s overall standard of living improves.” Gray Swoope, Secretary of Commerce President & CEO, Enterprise Florida, Inc. “This past year, our team succeeded in building the strong economic development partnerships needed to identify and win more competitive projects, strengthen international trade and sports development programs, and make it easier to do business in Florida. Our mission is to build on these results to elevate Florida’s economy into the most vibrant in the nation.” Enterprise Florida Senior Staff Gray Swoope Griff Salmon Melissa Medley John Webb Secretary of Commerce Executive Vice President Senior Vice President President President & CEO, & COO & CMO Florida Sports Foundation Enterprise Florida, Inc. -

FEDC Membership 12-2-19

First Name Last Name Suffix Company Name Job Title City State Chris Rietow Apalachee Regional Planning Council Executive Director Tallahassee FL Tyler Kitson Babcock Ranch Project Manager Punta Gorda FL Lucienne Pears Babcock Ranch VP Economic & Business Development Punta Gorda FL Erika Woods Babcock Ranch SVP of Legal Services Punta Gorda FL Darryl Register Baker County Development Commission Macclenny FL Becca Harden Bay Economic Development Alliance President & CEO Panama City FL Polly Jackson Bay Economic Development Alliance Director of Finance & Administration Panama City FL Garrett Wright Bay Economic Development Alliance Vice President Panama City FL Brian Cartland BDB of Palm Beach County VP Business Recruitment, Expansion & Retention West Palm Beach FL Shereena Coleman BDB of Palm Beach County VP Business Existing Industry West Palm Beach FL Tim Dougher BDB of Palm Beach County Vice President, Business Recruitment, Retention & Expansion West Palm Beach FL Gary Hines BDB of Palm Beach County Senior Vice President West Palm Beach FL Shawn Rowan BDB of Palm Beach County VP of Business Recruitment West Palm Beach FL Kelly Smallridge BDB of Palm Beach County President & CEO West Palm Beach FL Sharon Hillstrom Bradenton Area Economic Development Corp. President & CEO Bradenton FL Lauren Kratsch Bradenton Area Economic Development Corp. Director of Project Management Bradenton FL Max Stewart Bradenton Area Economic Development Corp. Director of Global Business Development Bradenton FL Patricia Evans Bradford County Development Authority -

Final Plan Was Submitted

PART 1 – INTRODUCTION TO THE PLAN I. CIRCUIT TRANSMITTAL INFORMATION A. Circuit number and listing of counties served in the circuit B. Local planning team convener (accountable circuit employee) 1. Name: Liesta Sykes 2. Title: Circuit 10 Community Relations Manager 3. Address (street, city, zip): 1055 HWY 17, Bartow, FL 33830 4. Telephone: (863) 534-7100, x.117 5. Fax: (863) 6. Email: [email protected] C. Local planning team chairman (if different from the convener) 1. Name: Kimberly Daugherty 2. Title: Chief Community Relations Officer 3. Address (street, city, zip): P.O. Box 1017, Bartow, FL 33830 4. Telephone: (863) 519-8900, x.204 5. Fax: (863) 519-8912 6. Email:[email protected] D. Circuit administrator 1. Printed name: Ann Berner 2. Signature: see cover page 3. Date of signature: see cover page II. PROCESS USED TO DEVELOP THE PLAN AND PLAN UPDATE A. Who led the planning effort The planning effort was jointly led by the Local Planning Team and designated staff members within Heartland for Children. B. Narrative description of the circuit and the demographics of the counties in the circuit – using 2008 Census data. Circuit 10 is comprised of three counties, Hardee, Highlands and Polk. The Circuit is located in central Florida and covers over 3,600 square miles. A large portion of the Circuit is rural with the major cities including Lakeland, Winter Haven and Sebring. Listed below is a demographic description of each county as listed by the U.S. Census Bureau. Hardee County is 623.7 square miles with 1 square mile of water, and as of 2008 Hardee County had a population of 28,888 making it the 51st most populous county in Florida. -

2005 Annual Report

2005 Florida Humanities Council Annual Report s Floridians we are constantly reminded GRANTS: During 2005, FHC funded grants totaling $368,522 for projects in 51 Florida communities. of the dynamic state in which we live: the These projects—created and carried out by orange grove we once passed on the way community residents and scholars—ranged from to work is now a mall; our neighborhood exhibits and programs on local history and culture; Cuban café is now home to a Thai to reading festivals, study groups, presentations, and discussions; to websites, cultural-tourism maps, Arestaurant; and at our local grocery store, the languages brochures, and CDs. A listing of the communities we overhear—once primarily English and Spanish—are that have benefited from FHC grants reads like a map increasingly languages and dialects from all over the of Florida. (See detailed list of all grants on next page. For a close-up on one community’s grant project, see world, especially Asian, Latin American, and Eastern the Newsletter’s front page.) European countries. The minute you think you have Florida in focus, the image blurs, the landscape shifts. TEACHERS: FHC’s seminars and workshops provided professional development, intellectual stimulation, and classroom resources to more than 650 teachers in 2005. Conducted by distinguished scholars, these programs on Florida history, literature, and cultural heritage enrich the teachers and ultimately benefit the students they teach in their classrooms. FHC’s Florida Center for Teachers offers weeklong and daylong seminars on a variety of Florida topics. FHC’s Landmarks of American History workshops offer weeklong, on-site studies of St. -

Highlands County, Florida Housing Study

Highlands County, Florida Housing Study May 2019 | FINAL Highlands County Ӏ Housing Study Table of Contents Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... i 1. Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 2. Economic Characteristics ....................................................................... 6 3. Demographic Characteristics .............................................................. 11 4. Multi-Family Market Performance ........................................................ 18 5. New Apartment Developments ........................................................... 21 6. Development Activity ............................................................................ 31 7. Supply and Demand Forecast .............................................................. 34 8. Rent Targets .............................................................................................. 37 9. Strategies and Recommendations ...................................................... 39 Appendix A: Stakeholder Interviews ........................................................ 51 Appendix B: Pro Forma Results .................................................................. 54 i Highlands County Ӏ Housing Study 1. Introduction In 2018, Highlands County received a Community Planning Technical Assistance grant to investigate market-rate, non-subsidized multi-family housing that -

2017 Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS)

COMPREHENSIVE Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) 2017 Economic Development District serving DeSoto • Hardee • Highlands Okeechobee • Polk COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 2017 CENTRAL FLORIDA ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DISTRICT SERVING DESOTO, HARDEE, HIGHLANDS, OKEECHOBEE, AND POLK COUNTIES United States Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration Atlanta Regional Offce Suite 1820 401 W Peachtree St, NW Atlanta, GA 30308-3510 Central Florida Regional Planning Council 555 E Church St., Bartow, FL 33830 863-534-7130 | www.cfrpc.org This document has been prepared with fnancial assistance from the U.S. Economic Development Administration. Florida Polytechnic University, Polk County Table of Contents Background and Key Regional Issues 3 Goals and Objectives 7 Target Industry Clusters 10 Opportunity and Investment Areas 13 For more information on the contents of the Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy, please view the CEDS Data Document at www.cfrpc.org/CEDS/ Guide economic A Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) growth is an ongoing planning process that requires participation and input from both the public and private sectors, along with the communities of a region. The CEDS is designed to guide economic growth by fostering a more stable and diversifed economy, to assist in the creation of jobs, and thereby improve the quality of life in Desoto, Hardee, Highlands, Okeechobee, and Polk counties. Assist in the creation of jobs The development of the CEDS is guided by the CEDS Committee. The Committee -

Florida's Heartland

FLORIDA’S HEARTLAND A BUSINESS LOCATION AT THE CENTER OF EVERYTHING DeSotoImmokalee Immokalee DeSoto | Glades | Hardee | Hendry | Highlands | Immokalee | Okeechobee BUSINESS DeSoto OPPORTUNITIES in DeSoto Immokalee DeSoto County is home to Florida’s first universal solar plant, major distribution DeSoto County facilities, the scenic Peace River and an inviting historic downtown in Arcadia, the at a Glance county seat. Agriculture, manufacturing City: Arcadia and tourism are among the county’s Area: 639 square miles major business sectors. Arcadia is situated at the intersection of two major state highways, offering swift movement, inbound or outbound, and fast arrival at domestic and global destinations. It is located an hour east of Sarasota and Bradenton and an hour north of Fort Myers. Walmart chose Arcadia as the site for a major distribution center, which now employs more than 500 associates. 4 | Florida’s Heartland Target INDUSTRIES n Agriculture n Logistics & Distribution n Alternative Energy n Tourism n Health Care BUSINESS ASSETS DeSoto County has much to offer businesses in a wide range of industries. The area’s key business assets include the following: Industrial Land DeSoto County has multiple industrial sites suitable for manufacturing, distribution or other types of businesses. 360-Degree Highway Network Businesses enjoy uncongested highway access to all parts of the state on I-75, I-4, I-95 and on the expanded U.S. 17 Corridor. Dual Rail Accessibility CSX and Seminole Gulf Railway connect to Florida’s statewide rail network, stretching from In the agriculture sector, DeSoto has more than 4,000 Jacksonville to Tampa, Palm Beach to Pensacola. -

2017 Annual Report

FY 2016-17 ANNUAL REPORT RICK SCOTT, Governor, Chairman, Enterprise Florida, Inc. 2017: FIGHTING TO SECURE FLORIDA’S FUTURE Florida has shown that cutting taxes, reducing regulations, creating business-friendly policies and keeping the cost of living down allows job creators to grow and succeed. We have cut taxes 75 times, saving Floridians more than $7.5 billion. We have paid down $9 billion in state debt and made government more efficient to save even more taxpayer money. In my seven years as Governor, we have made Florida a leader in job creation and consistently invested record funding in education, transportation and protecting our environment. In the four years before I took office, Florida had lost more than 800,000 jobs, taxes were increased by more than $2 billion and the economy was in freefall. Today, thanks to our hard work fighting for families, Florida’s economic growth strategy has become a model for the nation. Since 2011, Enterprise Florida and its statewide partners have helped me achieve my goal of making Florida the best job producing state in the nation, winning more than 1,000 competitive economic development projects. In 2016, projects established will keep and create 22,300 high- skill, high-wage private sector jobs in our state and generate $2.83 billion in capital investments. Over the last year, Enterprise Florida has restructured its business development strategies, focusing on targeted industries that bring high-paying jobs to our state. Together with the Department of Economic Opportunity, Enterprise Florida has worked to implement the $85 million Florida Job Growth Grant Fund I worked to establish with the Florida Legislature.