Jammed Elevator Prompts Twin-Turboprop Rejected Takeoff, Runway Over-Run

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home at Airbus

Journal of Aircraft and Spacecraft Technology Original Research Paper Home at Airbus 1Relly Victoria Virgil Petrescu, 2Raffaella Aversa, 3Bilal Akash, 4Juan M. Corchado, 2Antonio Apicella and 1Florian Ion Tiberiu Petrescu 1ARoTMM-IFToMM, Bucharest Polytechnic University, Bucharest, (CE), Romania 2Advanced Material Lab, Department of Architecture and Industrial Design, Second University of Naples, 81031 Aversa (CE), Italy 3Dean of School of Graduate Studies and Research, American University of Ras Al Khaimah, UAE 4University of Salamanca, Spain Article history Abstract: Airbus Commerci al aircraft, known as Airbus, is a European Received: 16-04-2017 aeronautics manufacturer with headquarters in Blagnac, in the suburbs of Revised: 18-04-2017 Toulouse, France. The company, which is 100% -owned by the industrial Accepted: 04-07-2017 group of the same name, manufactures more than half of the airliners produced in the world and is Boeing's main competitor. Airbus was Corresponding Author: founded as a consortium by European manufacturers in the late 1960s. Florian Ion Tiberiu Petrescu Airbus Industry became a SAS (simplified joint-stock company) in 2001, a ARoTMM-IFToMM, Bucharest subsidiary of EADS renamed Airbus Group in 2014 and Airbus in 2017. Polytechnic University, Bucharest, (CE) Romania BAE Systems 20% of Airbus between 2001 and 2006. In 2010, 62,751 Email: [email protected] people are employed at 18 Airbus sites in France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Belgium (SABCA) and Spain. Even if parts of Airbus aircraft are essentially made in Europe some come from all over the world. But the final assembly lines are in Toulouse (France), Hamburg (Germany), Seville (Spain), Tianjin (China) and Mobile (United States). -

Aero Twin, Inc. STC for Rudder Gust Lock

-- ST02540AK Aero Twin, Inc. 2403 Merrill Field Drive Anchorage, AK 99501 A43EU Airbus Defense and Space S. A. C-212-CB, CC, CD, CE, CF, DF, DE Fabrication and installation of Aero Twin, Inc., Rudder Gust Lock Kit No. 4111-212 on Airbus Defense and Space S. A. C-212 aircraft in accordance with Aero Twin, Inc., Master Data List No. 4111-212-MDL, Original Issue, dated May 8, 2020, or later FAA approved revision. : 1. The compatibility of this design change with previously approved modifications must be determined by the installer. 2. If the holder agrees to permit another person to use this Certificate to alter the product, the holder shall give the other person written evidence of that permission. 3. Instructions for Continued Airworthiness, Aero Twin, Inc. document number 4111-212-ICA, Original Issue, dated May 8, 2020, or later FAA accepted revision is a required part of this modification. 4. Airplane Flight Manual Supplement (AFMS), Aero Twin Doc. No. 4111-212-AFMS, Original Issue, dated August 27, 2020, or later FAA approved revision is a required part of this modification. November 20, 2017 September 8, 2020 _______________________________________________________ (Signature) August A. Asay Manager, Anchorage Aircraft Certification Office _______________________________________________________ (Title) _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Any alteration of this certificate is punishable by a fine of not exceeding $1,000, or imprisonment not exceeding 3 years, or both. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FAA FORM 8110-2(10-68) PAGE 1 of 2 PAGES This certificate may be transferred in accordance with FAR 21.47. INSTRUCTIONS: The transfer endorsement below may be used to notify the appropriate FAA Regional Office of the transfer of this Supplemental Type Certificate. -

Cross & Cockade International SERIALS with PHOTOGRAPHS

Cross & Cockade International THE FIRST WORLD WAR AVIATION HISTORICAL SOCIETY Registered Charity No 1117741 www.crossandcockade.com INDEX for SERIALS with PHOTOGRAPHS This is a provisional index of all the photographs of aircraft with serial numbers in the 46 years of the Cross & Cockade Journal. There are only photographs with identifiable serials, no other items are indexed. Following the Aircraft serial number is the make & model in parentheses, then page number format is: first the volume number, followed by the issue number (1 to 4) between periods with the page number(s) at the end. The cover pages use the last three characters with a 'c' (cover) 'f' - 'r'(front-rear), '1'(outside) '2' (inside). There are over 4180 entries in three categories, British individual aircraft, other countries individual aircraft, followed by airships & balloons. Regretfully, copies of the photographs are not available. Derek Riley, Jan. 22, 2017 AIRCRAFT SERIAL, BRITISH INDIVIDUAL...............................pg 01 AIRCRAFT SERIALS, OTHER COUNTRY...................................pg 13 AIRSHIPS & BALLOONS.............................................................pg 18 AIRCRAFT SERIAL, British individual 81 (Short Folder Seaplane) 07.1.024, 184 (Short Admiralty Type 184) 04.1.cr2, Serial Aircraft type Page num 07.1.027, 15.4.162 06.4.152, 06.4.cf1, 15.4.166, 16.2.064 2 (Short Biplane) 15.4.148 88 (Borel Seaplane) 15.4.167, 16.2.056 187 (Wight Twin Seaplane) 16.2.065 9 (Etrich Taube Monoplane) 15.4.149, 95 (M.Farman Seaplane) 03.4.139, 16.2.057 201 (RAF BE1) 08.4.150, 36.4.256, 42.3.149 46.4.266 97 (H.Farman Biplane) 16.2.057 202 (Bréguet L.2 biplane) 08.4.149 10 (Short Improved S41 Type) 23.4.171, 98 (H.Farman Biplane) 15.4.157 203 (RAF BE3) 08.4.152, 09.4.172, 20.3.134, 34.1.065 103 (Sopwith Tractor Biplane) 15.4.157, 20.3.135, 23.4.169, 28.4.182, 38.4.239, 14 (Bristol Coanda monoplane) 45.3.176 15.4.165 38.4.242, 41.3.162 16 (Avro 503) 15.4.150 104 (Sopwith Tractor Biplane) 03.4.143 204 (RAF BE4) 20.3.134, 23.4.176, 36.1.058 17 (Hydro Recon. -

List of Exhibits at IWM Duxford

List of exhibits at IWM Duxford Aircraft Airco/de Havilland DH9 (AS; IWM) de Havilland DH 82A Tiger Moth (Ex; Spectrum Leisure Airspeed Ambassador 2 (EX; DAS) Ltd/Classic Wings) Airspeed AS40 Oxford Mk 1 (AS; IWM) de Havilland DH 82A Tiger Moth (AS; IWM) Avro 683 Lancaster Mk X (AS; IWM) de Havilland DH 100 Vampire TII (BoB; IWM) Avro 698 Vulcan B2 (AS; IWM) Douglas Dakota C-47A (AAM; IWM) Avro Anson Mk 1 (AS; IWM) English Electric Canberra B2 (AS; IWM) Avro Canada CF-100 Mk 4B (AS; IWM) English Electric Lightning Mk I (AS; IWM) Avro Shackleton Mk 3 (EX; IWM) Fairchild A-10A Thunderbolt II ‘Warthog’ (AAM; USAF) Avro York C1 (AS; DAS) Fairchild Bolingbroke IVT (Bristol Blenheim) (A&S; Propshop BAC 167 Strikemaster Mk 80A (CiA; IWM) Ltd/ARC) BAC TSR-2 (AS; IWM) Fairey Firefly Mk I (FA; ARC) BAe Harrier GR3 (AS; IWM) Fairey Gannet ECM6 (AS4) (A&S; IWM) Beech D17S Staggerwing (FA; Patina Ltd/TFC) Fairey Swordfish Mk III (AS; IWM) Bell UH-1H (AAM; IWM) FMA IA-58A Pucará (Pucara) (CiA; IWM) Boeing B-17G Fortress (CiA; IWM) Focke Achgelis Fa-330 (A&S; IWM) Boeing B-17G Fortress Sally B (FA) (Ex; B-17 Preservation General Dynamics F-111E (AAM; USAF Museum) Ltd)* General Dynamics F-111F (cockpit capsule) (AAM; IWM) Boeing B-29A Superfortress (AAM; United States Navy) Gloster Javelin FAW9 (BoB; IWM) Boeing B-52D Stratofortress (AAM; IWM) Gloster Meteor F8 (BoB; IWM) BoeingStearman PT-17 Kaydet (AAM; IWM) Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat (FA; Patina Ltd/TFC) Branson/Lindstrand Balloon Capsule (Virgin Atlantic Flyer Grumman F8F-2P Bearcat (FA; Patina Ltd/TFC) -

Aviation Maintenance Alerts

ADVISORY CIRCULAR 43-16A AVIATION MAINTENANCE ALERTS ALERT FEBRUARY NUMBER 2006 331 CONTENTS AIRPLANES AVIAT .........................................................................................................................................1 BEECH ........................................................................................................................................2 CESSNA ......................................................................................................................................4 DASSAULT.................................................................................................................................6 GULFSTREAM...........................................................................................................................8 ISRAEL AIRCRAFT.................................................................................................................11 PIPER.........................................................................................................................................13 RAYTHEON..............................................................................................................................15 HELICOPTERS AGUSTA ...................................................................................................................................16 POWERPLANTS PRATT & WHITNEY ...............................................................................................................16 ACCESSORIES AERO-TRIM .............................................................................................................................18 -

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War INCLUDING Lightning Canberra Harrier Vulcan www.keypublishing.com RARE IMAGES AND PERIOD CUTAWAYS ISSUE 38 £7.95 AA38_p1.indd 1 29/05/2018 18:15 Your favourite magazine is also available digitally. DOWNLOAD THE APP NOW FOR FREE. FREE APP In app issue £6.99 2 Months £5.99 Annual £29.99 SEARCH: Aviation Archive Read on your iPhone & iPad Android PC & Mac Blackberry kindle fi re Windows 10 SEARCH SEARCH ALSO FLYPAST AEROPLANE FREE APP AVAILABLE FOR FREE APP IN APP ISSUES £3.99 IN APP ISSUES £3.99 DOWNLOAD How it Works. Simply download the Aviation Archive app. Once you have the app, you will be able to download new or back issues for less than newsstand price! Don’t forget to register for your Pocketmags account. This will protect your purchase in the event of a damaged or lost device. It will also allow you to view your purchases on multiple platforms. PC, Mac & iTunes Windows 10 Available on PC, Mac, Blackberry, Windows 10 and kindle fire from Requirements for app: registered iTunes account on Apple iPhone,iPad or iPod Touch. Internet connection required for initial download. Published by Key Publishing Ltd. The entire contents of these titles are © copyright 2018. All rights reserved. App prices subject to change. 321/18 INTRODUCTION 3 RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War cramble! Scramble! The aircraft may change, but the ethos keeping world peace. The threat from the East never entirely dissipated remains the same. -

CAA - Airworthiness Approved Organisations

CAA - Airworthiness Approved Organisations Category BCAR Name British Balloon and Airship Club Limited (DAI/8298/74) (GA) Address Cushy DingleWatery LaneLlanishen Reference Number DAI/8298/74 Category BCAR Chepstow Website www.bbac.org Regional Office NP16 6QT Approval Date 26 FEBRUARY 2001 Organisational Data Exposition AW\Exposition\BCAR A8-15 BBAC-TC-134 ISSUE 02 REVISION 00 02 NOVEMBER 2017 Name Lindstrand Technologies Ltd (AD/1935/05) Address Factory 2Maesbury Road Reference Number AD/1935/05 Category BCAR Oswestry Website Shropshire Regional Office SY10 8GA Approval Date Organisational Data Category BCAR A5-1 Name Deltair Aerospace Limited (TRA) (GA) (A5-1) Address 17 Aston Road, Reference Number Category BCAR A5-1 Waterlooville Website http://www.deltair- aerospace.co.uk/contact Hampshire Regional Office PO7 7XG United Kingdom Approval Date Organisational Data 30 July 2021 Page 1 of 82 Name Acro Aeronautical Services (TRA)(GA) (A5-1) Address Rossmore38 Manor Park Avenue Reference Number Category BCAR A5-1 Princes Risborough Website Buckinghamshire Regional Office HP27 9AS Approval Date Organisational Data Name British Gliding Association (TRA) (GA) (A5-1) Address 8 Merus Court,Meridian Business Reference Number Park Category BCAR A5-1 Leicester Website Leicestershire Regional Office LE19 1RJ Approval Date Organisational Data Name Shipping and Airlines (TRA) (GA) (A5-1) Address Hangar 513,Biggin Hill Airport, Reference Number Category BCAR A5-1 Westerham Website Kent Regional Office TN16 3BN Approval Date Organisational Data Name -

Joint Workshop

BIOGRAPHIES Douglas Andrew Lead Infrastructure Specialist The World Bank ______________________________________________________________________ Doug Andrew is a Lead Infrastructure Specialist at the World Bank. .He recently retired as Group Director Economic Regulation and member of the UK Civil Aviation Authority Board. He is an Associate Fellow at Warwick University Business School. Previously he was Deputy Secretary, Tax and Regulation, in the New Zealand Treasury. He led the CAA in its economic regulation of and application of competition policy to privately and state-owned UK airports, airlines together with the air traffic control. He was a founding member of EUROCONTROL’s Performance Review Commission. He has Masters degrees in economics and public policy from Princeton and Auckland Universities. Adam R Brown Vice President – Customer Affairs Directorate Airbus SAS ______________________________________________________________________ Adam Brown was born in Kirdford, England in 1940 and educated at Rugby School and Peterhouse, Cambridge, from which he received a Master's degree in Mechanical Sciences. He joined the de Havilland Aircraft Co., then part of Hawker Siddeley Aviation, in 1962, working first in sales engineering and subsequently in sales. In 1973 he came to Airbus as General Sales Manager. After a variety of senior assignments in sales, marketing, strategy and forecasting, Adam Brown assumed his present function in April 2004. In this position, his task is to increase Airbus’s formal presence at external events and to ensure that Airbus’s position is well represented throughout the industry. In recognition of his contribution to Anglo-French aeronautical collaboration, Adam Brown has been appointed a Chevalier in the French national Order of Merit. -

The Connection

The Connection ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2011: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2011 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISBN 978-0-,010120-2-1 Printed by 3indrush 4roup 3indrush House Avenue Two Station 5ane 3itney O72. 273 1 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 8arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 8ichael Beetham 4CB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air 8arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-8arshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman 4roup Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary 4roup Captain K J Dearman 8embership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol A8RAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA 8embers Air Commodore 4 R Pitchfork 8BE BA FRAes 3ing Commander C Cummings *J S Cox Esq BA 8A *AV8 P Dye OBE BSc(Eng) CEng AC4I 8RAeS *4roup Captain A J Byford 8A 8A RAF *3ing Commander C Hunter 88DS RAF Editor A Publications 3ing Commander C 4 Jefford 8BE BA 8anager *Ex Officio 2 CONTENTS THE BE4INNIN4 B THE 3HITE FA8I5C by Sir 4eorge 10 3hite BEFORE AND DURIN4 THE FIRST 3OR5D 3AR by Prof 1D Duncan 4reenman THE BRISTO5 F5CIN4 SCHOO5S by Bill 8organ 2, BRISTO5ES -

2018 KODIAK 100, Series II Serial Number: 100-253 Registration: N352CL

2018 KODIAK 100, Series II Serial Number: 100-253 Registration: N352CL www.modern-aviation.com | [email protected]| 1.206.762.6000 2018 KODIAK 100, Series II Serial Number: 100-253 Registration: N352CL AIRCRAFT HIGHLIGHTS • Upgraded Timberline Interior Seating • TKS Ice Protection • 10-Place Oxygen Upgrade • Air Conditioning • Garmin G1000 Nxi Avionics Suite Airframe Total Time Since New Airframe 60 Hrs Engine 1 60 Hrs Modern Aviation Aircraft Sales *All Specifications subject to independent verification Options Options Installed on Kodiak S/N 253 Kodiak Series II Standard Equipped Aircraft $2,150,000 Series II Paint Scheme allover white with black and silver stripes External baggage compartment $94,500 TKS Ice Protection System (Tank in Cargo Pod) $124,500 29” Tire Combo $1,750 GTS 800 TAS/WX-500 Stormscope Package $28,700 GDL 69A-XM Data Link with Audio Infotainment $6,950 ChartView Enable Card $5,000 Timberline Interior (Warm Brown) 4 seats $20,000 2 additional seats $17,700 10-place oxygen system $10,000 Bose A20 Headset (Passenger) (x2) $ 2,190 Air Conditioning $42,500 Total Retail Price as Optioned $2,503,790 Modern Aviation Aircraft Sales *All Specifications subject to independent verification Avionics and Equipment AVIONICS ENGINE INSTRUMENTS (Fully integrated in the G1000NXI) •Garmin G1000NXi Integrated Avionics Suite: • Torque (ft-lb) • RPM Prop •(2) Primary Flight Displays – PFD • ITT •Multifunction Display – MFD • RPM NG (%) •All three are next gen, high resolution 10. inch displays • Oil Temp/Pressure •Enhanced -

The Finnish Air Force BAE Systems Hawk

The Finnish Air Force t Hawk 66 Hawk 51 BAE Systems Hawk The BAE Systems Hawk is a British single-engined two-seat advanced jet trainer. The Finnish Air Force's Hawks bear the military designation HW and are operated by Fighter Squadron 41 of the the Air Force Academy, primarily in advanced and tactical training roles. In the Hawk, a cadet pursuing a fighter pilot's career gets his or her first taste of jet flying after having learnt basic flying skills at the controls of a piston-engined aircraft. The first (advanced) Hawk training phase, designated HW 1, starts during the second year of cadets' studies in the National Defence University and consists of Hawk type rating, navigation, instrument flying, aerobatics, formation flying, and night flying. The next (lead-in) phase, known as HW 2, focuses on tactical training and consists of basic air-to-air and air-to-ground work before students progress to the more demanding Hornet multi-role fighter. The Hawk can also carry air sampling pods that were used extensively during the volcanic ash crisis in the spring of 2010. The Hawk has has limited engagement capability against attack aircraft, helicopters and other equivalent targets under favorable conditions. The Hawk is also flown by the Air Force's official display team the Midnight Hawks, in which case the team's four aircraft are fitted with smoke generators for enhanced visual effect. Team pilots are flight instructors. During the 2017 display season six aircraft used by the team received a special blue-and-white livery in celebration of the 100th anniversary of Finland’s independence. -

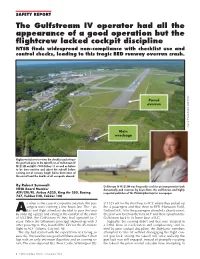

The Gulfstream IV Operator Had All the Appearance of a Good Operation But

SAFETY REPORT The Gulfstream IV operator had all the appearance of a good operation but the flightcrew lacked cockpit discipline NTSB finds widespread non-compliance with checklist use and control checks, leading to this tragic BED runway overrun crash. Paved overrun Source: Massachusetts State Police Main wreckage Flightcrew failure to review the checklist and release the gust lock prior to the takeoff run of Gulfstream IV N121JM on BED’s 7000-ft Rwy 11 as well as failure to be time-sensitive and abort the takeoff before running out of runway length led to destruction of the aircraft and the deaths of all occupants aboard. By Robert Sumwalt Gulfstream IV N121JM was frequently used for air transportation both NTSB Board Member domestically and overseas by Lewis Katz, the well-known and highly ATP/CFII/FE. Airbus A320, King Air 350, Boeing respected publisher of The Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper. 737, Fokker F28, Fokker 100 s often is the case in corporate aviation, the pas- at 1325 edt for the short hop to ACY, where they picked up sengers were running a few hours late. The 2 pi- the 4 passengers and flew them to BED (Hanscom Field, Alots and flight attendant decided to pass the time Bedford MA). After the passengers attended a charity event, by ordering a pizza and eating in the comfort of the cabin the plan was to return them to ACY and then reposition the of N121JM, the Gulfstream IV they had operated for 7 Gulfstream back to its home base at ILG. years. When the billionaire principal showed up with 3 Tragically, the evening didn’t end that way.